Volume 10 of the OJBR presents Intonation in the Performance of the Double Bass: The Role of Vision and Tact in Undershoot and Overshoot Patterns by Fausto Borém and Guilherme Menezes Lage.

Abstract: The research question of this paper was partially motivated by the need for better control of the double bass performance and partly motivated by the friction of opinions in the international double bass community about using or not using marks on the double bass fingerboard. Obtaining an accurate intonation is a universal problem in the performance of non-tempered stringed instruments (with no frets) such as the members of the violin family. Musicians commonly land their fingers too short (undershoot) or too long (overshoot) for aimed locations (target notes), resulting in poor intonation. This study aims at understanding how the sensorial guidance of vision and tact could interfere in the erroneous movement patterns of undershoot and overshoot. As an interdisciplinary study (music performance and motor behavior), it analyzed the performance of professional musicians in two movement conditions: with and without sensorial guidance. The results showed that sensorial cues conditions compared against no-guidance conditions create: (1) an overshoot pattern instead of an undershoot pattern and (2) a more accurate intonation on the double bass, which were discussed based on the role of visual and tactile information on motor control of the left limb. Summarizing this research, the results show that visual and tactile strategies can improve the performance of double bassists.

Keywords: accuracy in double bass performance; undershoot and overshoot double bass patterns; control of non-tempered intonation; left hand movements in music performance.

". . . from 'learn the sweet spots by ear and feel alone . . .' to 'cheat dots all over the places . . . .'" Comment from one out of 282 double bassists in a polemic international discussion (Chalmers & Pierce, 2016, at [0:29]).

The above epithet was taken from the speech of a beginner on the double bass and reflects one of the most controversial and passionate discussions in the international community of bass players. Not long ago, there was a tendency for popular bassists to accept marks in the fingerboard as a natural strategy and, on the other hand, a tendency for classical bassists to reject them. But this binary division is no longer so clear, as Avibigband (2016) illustrates: "... many of the best players in the world sometimes use them [the dots]. [Edgar] Meyer, [Boguslaw] Furtok, [Božo] Paradžik, [Rick] Stotijn, many more." In the link goo.gl/6m8E6M of another blog, Double Bassists (Contrabassists), the post shared on August 1, 2017 (Brown, 2017) had 282 comments from both segments, popular and classic, many of which quite fierce, accusative or biased, including remarks such as "lazy", "dots = no practice", "stupid", "self-taught", "buy a kazoo", "dots suck", "You cannot play if you're looking at dots", or else "ego trip", "Reminds me of the old Reagan Era 'do not do drugs' commercials", "purists will unleash their fury", to find no hint of agreement, pictured childish disputes such as "Edgar does not use the dots" followed by a "Yes, Meyer uses guides" and so on.

But all comments shared a lack of scientific knowledge about what Applebaum (1973, p.15) calls "the universal problem" of orchestral strings and Havas (1995) names as the main cause of an anxiety that leads musicians of the violin family to abandon music as a profession. If both tactile and visual intonation strategies are used by role model musicians such as Grammy Award winning bassist Edgar Meyer (Welz, 2001) and others, they are used only intuitively. Even when these sensorial cues are exploited in teaching methods as a guidance procedure to improve intonation (Barber, 1990, 1991; Green, 1980; Robinson, 1990; Starr & Suzuki, 1976), they still lack the support of systematic research.

After this introduction, we present a review of the literature (II), the research method (with the participants, recording apparatus, tasks, procedures and analyses of audio recordings) (III), the results (IV), and the discussion with conclusions (V).

Traditionally, music teachers and performers of non-tempered instruments have long believed that proprioceptive and auditory information are the main feedback sources in movement control. Auditory information is an anticipative sense (Bender, Resch, Weisbrod, & Oelkers-Ax, 2004) but, when left-hand fingers lose contact with the fingerboard, it does not produce relevant information to adjust the ongoing movement and acts solely as feedback during the fine adjustments after the note has started (Borém et al, 2006). So, musicians are left only with proprioceptive information during the movement.

Motor learning is a complex process of movement control changes over a span of time that focuses on the acquisition of skills due to practice. During the process of teaching and learning to play a musical instrument, no matter the pedagogical approach, both teacher and student usually face problems in the execution of movements essential to performance. Although Morrison and Fyk (2002, p.194) call attention to the fact that in the musician's real world ". . . intonation appears to be more negotiation than conformity. . .", they also agree that pitch control is a goal that musicians should strive for. The basic knowledge consolidated in the area of motor control can shed some light into several questions still not investigated in the field of music. This article focuses on the evaluation of pitch control skills as result of movement in a controlled environment, hence the experimental nature of this study. It is our hope to offer some insights that may partly apply to real music making double bassists face on stage.

Non-tempered orchestral stringed instruments (violin, viola, cello and double bass) have no frets on their fingerboards (as opposed to, e.g., guitar and electric bass) to indicate where the fingers must land for each note. This enormous challenge requires a high level of accuracy because slightest variations in pointing the left hand's fingers deteriorate intonation (Sloboda, 1996). The analysis of accuracy of the upper left limb movement towards a musical note in the fingerboard shows that when the finger does not reach the target, it lands either too short (undershoot) or too long (overshoot). These two types of errors, observed in movement amplitude during music performance may generate consistent undershoot or overshoot patterns caused by several factors inherent to manual movement control. Moreover, they usually reflect the participation of error correction mechanisms.

Constraint of sensorial sources in the preparation and execution (including corrections) of the movement during the gesture plays an important role in undershoot and overshoot patterns. The restriction of vision, for example, and that includes the bassist not looking at the fingerboard to play, leads performers predominantly to an undershoot pattern (Elliott et al., 2014; Proteau & Isabelle, 2002). One of the explanations is that in the programming of movements directed to a target, two phases take place. Initially, a subcomponent of the movement is generated, which tends to undershoot the target. Subsequently, as the limb approximates the target, final corrections need to be made to reach the objective precisely. However, these final corrections are performed with higher accuracy when the performer resorts to visual information (Khan & Franks, 2003; Lage et al., 2014).

In experimental music research, leading studies have been conducted mainly on auditory feedback (Gabrielsson, 2003), ignoring visual and tactile aspects of performance. Not surprisingly, in the context of music performance pedagogy, the great majority of consolidated teaching methods of orchestral non-tempered strings (violin, viola, cello and double bass) do not include vision or tact as important sensorial sources to improve intonation, relying only on audition and proprioception1 in the generation of essential information for movement production and control (Lage et al., 2007). Only a few leading pedagogues such as Paul Rolland (Rolland & Mutschler, 1986) and Shinichi Suzuki (Starr & Suzuki, 1976) intuitively mention the role of vision for the novice in locating markers on the instrument fingerboard, but only as a temporary sensorial source, subsidiary to the audition/proprioception combination. As far as tact goes, also intuitively, Galamian (1962, p.21-22) talks about the left hand "double contact" to secure intonation, but he limits his approach to very few and imprecise tactile references of the instrument (in his own words, "side of the neck", "body of the violin", "various parts of the instrument" and "right side rim") or the violinist's non-specific body areas ("side of the first finger" and "lower part of hand"). His non-scientific approach has major contributions to violin playing technique and pedagogy, but it is far from providing precise anchors for intonation control. Galamian is also against the triple physical contact of the left hand as if it would prevent expressiveness, such as in the use of vibrato.

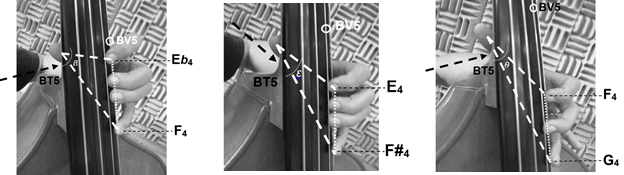

But the triple contact of the left hand on the instrument does not prevent expressiveness if the player uses it punctually and briefly, dismounting the fingers fixed positions right after locating the target note. Moreover, the use of a triple contact anchor provided by the thumb being the vortex of a triangle formed with two other left-hand fingers, combined with three specific reference points of the double bass (1- the nut, the saddle, 2- the meeting point between neck and 3- the top of the bass, respectively) may provide precise tactile anchors (Figure 1) for the double bassist to nail down target notes (Borém, 2011).

Figures 1a, 1b, 1c — Examples of intonation control on the double bass by means of triangular left-hand shapes ("triple contact") combining the BT5 vortex and its angles (Borém, 2011, p.91-92).

Some other factors influence undershoot and overshoot patterns in manual movements. The movement execution is affected by both initial position of the limb and interpolated movements that may be characterized by random direction (Carlton & Carlton, 1984; Imanaka, 1989). Thus, in the performance of non-tempered musical instruments such as the double bass, a constant change in the initial position of the upper left limb (a permanent demand in music performance since melody is constructed from continuous shifts of notes) may cause difficulties in the adjustments for the fingers to reach the required positions in the fingerboard. Moreover, during the performance, proximal-to-distal movements and distal-to-proximal movements on non-tempered strings are naturally and continuously interpolated, generating a greater probability of producing undershoot or overshoot patterns. It should be observed that, in both double bass and cello, ascending pairs of pitches occur in descending proximal-to-distal movements, while in the violin and viola, ascending pairs of pitches occur in horizontal distal-to-proximal movements.

Another influence factor is movement direction, which is constrained by biomechanical variables. Movements on the double bass can be performed in opposition (ascending) or in congruence (descending) with the gravitational force creating different levels of energy costs to the system. Precision and movement control of limbs may be differently influenced by gravity (Lackner & DiZio, 2000). Target undershooting is more pronounced under conditions in which relative temporal costs of a target overshoot become greater than undershooting (Elliott et al., 2014; Elliott, Hansen, Mendoza, & Tremblay, 2004). In a descending distal-to-proximal movement, a target overshoot requires lower energetic and temporal costs to make corrections than in an ascending proximal-to-distal fashion due to gravitational effects on antagonist muscles activation (Lyons, Hansen, Hurding, & Elliott, 2006; Roberts, Elliott, Lyons, Hayes, & Bennett, 2016). It is important to point out that these experimental findings were only observed in proximal-to-distal movements.

Not many of the most recognized methods of orchestral strings teaching cover the relation between intonation control and left upper limb movement in ascending and descending pairs of pitches. However, there seems to be an agreement within this vast non-theoretical literature that intonation control is more difficult in descending pair of pitches (from a higher to a lower fundamental pitch frequency; fundamental pitch frequency is simply referred in this paper from here on as frequency or F0) in both more horizontal movements, such as in both violin and viola (Havas, 1979, 1995) and more vertical movements, such as in both cello and double bass (Kenneson, 1974). Only a few and not conclusive experimental studies have been done on intonation regarding the musician's tendencies of sounding out-of-tune above or below the target note. Madsen (1966) found that overall pitch deviation was closer to equally tempered target notes in descending scales than in ascending ones. Kantorski (1986) and Sogin (1989) showed that advanced string players performed descending whole-tone tetrachords (a tonally instable scale fragment) sharper than in the opposed ascending fashion. On the contrary, Yarbrough and Ballard (1990), also studying advanced string players, stated that their performance was sharper in ascending pairs of pitches.

In spite of these contradictory results, which illustrate the challenge in reaching every next target note in non-tempered string playing, there may be a perception among musicians that it is less uncomfortable and embarrassing to be out-of-tune within the same melodic direction (that is, the need to complete the movement to reach the target note) than having to slow down, stop and initiate the movement in contrary direction to reach back the desired target note, which he or she just slid through. Although there are no studies with humans relating preference for melodic contour, McKenna, Weinberger and Diamond (1989) found different levels of auditory perception for the same note within different melodic contours in cats. In other words, instrumentalists may feel less uncomfortable performing these ascending pair of pitches that did not achieved the target pitch due to their auditory perception and because they did not have to activate antagonistic muscles and initiate an opposite movement and, thus, produce a stronger frequency interference in the process. This would also corroborate the idea in which smaller temporal and energy costs prevail (Lyons et al., 2006).

The interaction of these interfering factors in the production of undershoot or overshoot patterns can be summarized in the complex intonation scenario which Applebaum and Applebaum (1973, p. 15), as mentioned above, called "the universal problem" in orchestral string playing. Lage et al (2007) investigated the role of sensorial information in the control of the non-tempered intonation on the double bass and found greater precision and lower variability when tactile and visual cues were simultaneously available in its performance. These findings corroborate results of other studies on the efficiency of vision and haptic information in motor control (Elliott et al., 2014; Khan & Franks, 2003; Rabin & Gordon, 2004).

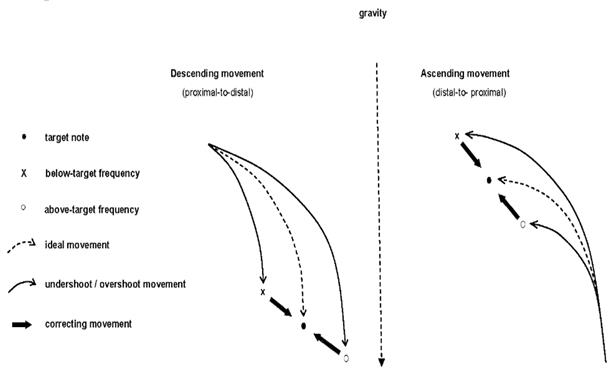

On the double bass, undershoot in descending movements (proximal-to-distal) means an achieved frequency below the target pitch, while overshoot refers to an achieved frequency above the target pitch (Figure 2). Thus, undershoot here means a shorter distance covered (in mm) and corresponds to a smaller frequency (in Hz) achieved. On the other hand, in ascending movements, the reasoning is the opposite: undershoot means an achieved frequency above the target pitch, while overshoot refers to an achieved frequency below the target pitch. In other words, undershoot in ascending movements on the double bass means a shorter distance covered but a higher frequency achieved. In this article, undershoot and overshoot were inferred from the frequency achieved related to movement direction (ascending or descending).

Figure 2 — Intonation problems in shifting on the double bass: undershoot (below-target frequency) and overshoot (above-target frequency) in both descending (proximal-to-distal) and ascending (distal-to-proximal) left hand movements.

In short, sensorial constraints and movement direction may play an important role on undershoot and overshoot patterns in musical performance on the double bass. To extend Lage et al. (2007) findings, it was investigated how sensorial guidance influences undershoot and overshoot patterns (1) on overall measurement of performance independent of movement direction, (2) on descending movements and (3) on ascending movements. Moreover, it also observed the role of sensorial guidance on performance accuracy and variability.

In the overall analysis, it was hypothesized that the integration of specific visual and tactile cues (1) improves the accuracy and consistency of musical performance and (2) creates a less pronounced undershoot pattern compared to the no-guidance performance. Furthermore, in the analysis of movement direction, it was expected that the no-guidance condition in descending movements, compared to the sensorial guidance condition, produces a more pronounced undershoot pattern (achieving a frequency below the target pitch). On the other hand, the no-guidance condition in ascending movements should create a more pronounced undershoot pattern due to the uncertainty of movement control in association with gravitational constraints (achieving a frequency above the target pitch). In other words, resorting to vision and tact not only would improve intonation in general on the double bass but also would prevent patterns within the common fear to not reach the target note in shifts to the high register of the instrument.

1Sense of body position and orientation signaled by muscles, joint receptors, and receptors located in the inner ear (Schmidt and Lee, 1999).

1. Participants

Seven professional double bassists (mean of 9.6 ± 2.5 years of professional practice) with no prior experience with the procedures, volunteered to take part in the experiment, which was carried out according to the ethical guidelines laid down by the local Ethical Research Committee.

2. Recording apparatus

A very common size double bass (3/4 type; string length of 106 cm) was used in the experiment. Audio signals were detected with a pick up (Fishman BP-100) attached with a clamp to the bridge of the musical instrument. The signals were amplified by a mixer (Staner 04-2S) and connected to the line input of a computer sound card, being sampled at 22.050 samples per second, 16 bits per sample.

3. Tasks

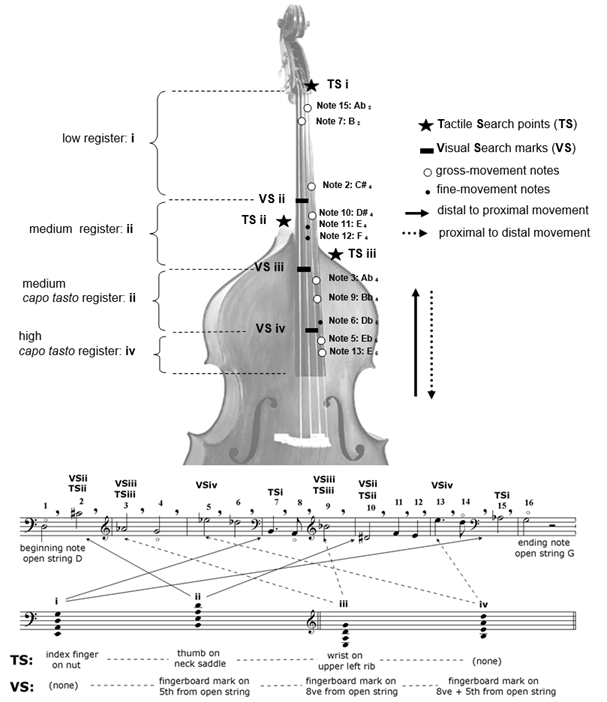

A sequence of spatialized target notes (Figure 3) having no intended musical meaning and encompassing all four registers of the double bass (C4 being the C in the middle of the piano keyboard) was played in two conditions by the participants. This sequence of 16 notes was designed to have a scattered non-melodic atonal nature in order to make it practically impossible to be memorized at first sight, or even after a few repetitions. The equal-tempered scale was chosen because it is the most common scale used in music teaching (sight singing, ear training, melodic and harmonic dictation, etc.) and therefore the one the great majority of modern musicians are used to. In all sensorial conditions of the trials, pauses ranging from 1.0-5.0 seconds between long notes with 0.5-1.5 seconds of duration were mandatory. The participants were asked not to adjust their left hands after the beginning of the attempted note. In the few instances where adjustments happened (less than 1%), the participant was asked to repeat the note. Adjustments were detected either by spectrographic analysis of the audio signals or directly by an assistant who visually monitored left hand gestures. To avoid intonation instabilities due to poor or variable bow control, the notes were played pizzicato. The double bass' strings were electronically tuned based on the orchestral A4 of 440 Hz. The double bass is a transposing instrument and its notes sound one octave lower than the written pitches; a C#4 (the second note of the atonal sequence), for example, produces a C#3.

Figure 3 — The double bass with Tactile Search points (TS), Visual Search marks (VS), 11 target notes (notes 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13 and 15) of spatialized atonal sequence and corresponding music staff with target notes.

4. Procedures

The musical sequence was presented to the participants on a blackboard with staves located two meters in front of them. Each participant played the musical sequence two times with an interruption of 5 minutes between them, each trial having a different use of sensorial constraints. In order to prevent gliding between notes (that is, sliding the playing finger during the trajectory to the target note) and repeated bias throughout the sequence, the participants were instructed to take their hands off the double bass fingerboard after playing every note, as can be inferred by the commas between adjacent notes in the atonal sequence (see Figure 3 above).

In the trial based on visual and tactile orientation, the following location cues (see Figure 3 above) were given to the participants during the experiment: (1) three Tactile Search points (TS i, TS ii and TS iii) located in three different places of the instrument body (namely the nut touched by the index finger, the saddle nut touched by the thumb and left upper rib nut touched by the wrist, respectively; see Figure 3); and (2) three Visual Search marks (VS ii, VS iii and VS iv), namely white dots attached to the fingerboard, signaling the intervals of the perfect fifth, perfect octave and perfect thirteenth (one octave plus a perfect fifth) departing from the open strings, respectively (see Figure 3). The tactile and visual cues have a complementary role as the TSs covers the lower range (registers i and ii) and the VSs covers the higher ranges (registers ii, iii and iv), what yields an overlapping area in the middle register (see Figure 3 above). A research assistant monitored every trial to guarantee that the participants respected the previous orientations and sensorial constraints.

The trials were performed as follows. Having been introduced to the sequence of notes, written on a music blackboard in front of the player, the participant performed two trials on the double bass: (1) the Free Trial (performance based on the musician's previous experience, without instructions on TS or VS), which served as a control trial and (2) the Integrated Trial (performance based on the integration of tactile and visual guidance, that is, TS and VS).

The rationale for the no-random order of the trials was intentionally based on the following aspects: (1) the Free Trial was the first to be performed in order to allow the participant to use his/her own intonation strategies and (2) the Integrated Trial was performed after the Free Trial to avoid conscious simultaneous use of sensorial cues. The learning effect is not to be found in this sequence due to its atonal, spatialized and fragmented nature, what, as mentioned before, makes it very difficult to be memorized even after several trials (Lage at al, 2007).

From the 16 notes of each trial (Free Trial and Integrated Trial), 5 notes were to be performed with open strings (that is, no use of the left hand) and therefore to be discarded, remaining 11 notes for the analysis. The recorded sequences were analyzed as described in the next section.

5. Analyses of audio recordings

The audio files were processed by custom-made software implementing the so-called Super Resolution Algorithm (Medan, Yair, & Chazan, 1991). This fundamental frequency (F0) tracker based on the cross-correlation function was designed for speech analysis but was found to be robust and precise for the analysis of double bass audio signals. To avoid gross errors that may occur in F0 extraction methods, where the algorithm may track half or twice values of fundamental frequencies, search intervals were limited to ±25% (approximately the interval of a major third) around the correct frequency of each note. The correct frequency ( f ) of a note distant n semitones from the base frequency (440 Hz) was computed as  , where

, where  is the constant for equal-temperament, and n > 0 for f > 440 Hz (and vice-versa).

is the constant for equal-temperament, and n > 0 for f > 440 Hz (and vice-versa).

The estimated frequency of each note was the average value over the respective duration. In order to check the measurements, automatically determined frequencies were compared with approximate values manually extracted from narrow-band spectrograms. In a few cases, where the performed note was outside the ±25% search range, the automatic detection was repeated around the value manually read from the spectrogram. A total of 154 values (7 participants ´ 2 trials ´ 11 notes) were then analyzed. In order to compare the measured frequency ( ) with the respective theoretical value ( f ), the magnitude of the relative error,

) with the respective theoretical value ( f ), the magnitude of the relative error, , was computed for each of the 154 notes. Statistical analyses were carried out, as detailed below.

, was computed for each of the 154 notes. Statistical analyses were carried out, as detailed below.

For each of the seven participants, error values were organized into 2 blocks, one per trial, each block having 11 valid notes, from which the absolute mean error, its respective standard deviation and constant error were initially calculated. Next, individual errors beyond two standard deviations from the respective block mean were discarded as outliers. This filtering process removed less than 1% of the data. Finally, the absolute relative error (RE), RE standard deviation (SDRE) and the signed relative error (SRE) were computed for each trial over the seven participants. The RE values provide information about the performance accuracy, the SDRE values are related to response consistency and the SRE values, which are the main point of this study, provide information about error direction (undershoot or overshoot patterns). The SRE was analyzed as follows: (1) eleven notes, regardless of movement direction, (2) six notes, performed in descending movements and (3) five notes, performed in ascending movements, respectively.

It should be noticed that a RE of 6% roughly equates the interval of a semitone, and the just noticeable changes in frequency is approximately 0.7% (Zwicker & Fastl, 1990). The non-parametric Wilcoxon Test was used to compare the means between trials (Free and Integrated Trials) in three dependent measurements. A significant level of 0.05 was adopted.

1. Absolute Relative Error mean (RE) and Standard Deviation of the Relative Error mean (SDRE)

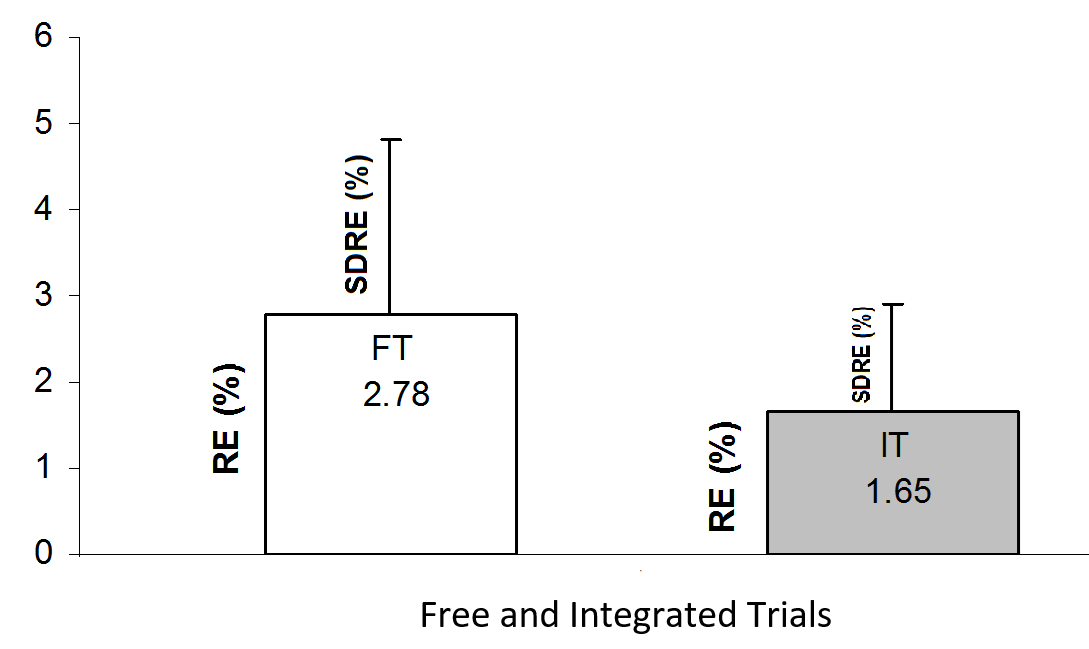

A significant difference was detected between FT and IT trials for RE (Z = 2.02, p = .04). The participants showed a better performance, as far as intonation goes, in the Integrated Trials than in the Free Trial (Figure 4). A marginal difference between trials was found in the SDRE analysis (Z = -0.85, p = .06), indicating a tendency of the Integrated Trial to be more consistent compared to the Free Trial (Figure 3).

Figure 4 — Comparisons of RE (Absolute Relative Error) and SDRE (Standard Deviation of the Relative Error) between Free Trials (in white) and Integrated Trials (in grey) of double bassists trying to reach target notes in descending, ascending and overall movements of the left hand.

2. Signed Relative Error mean (SRE)

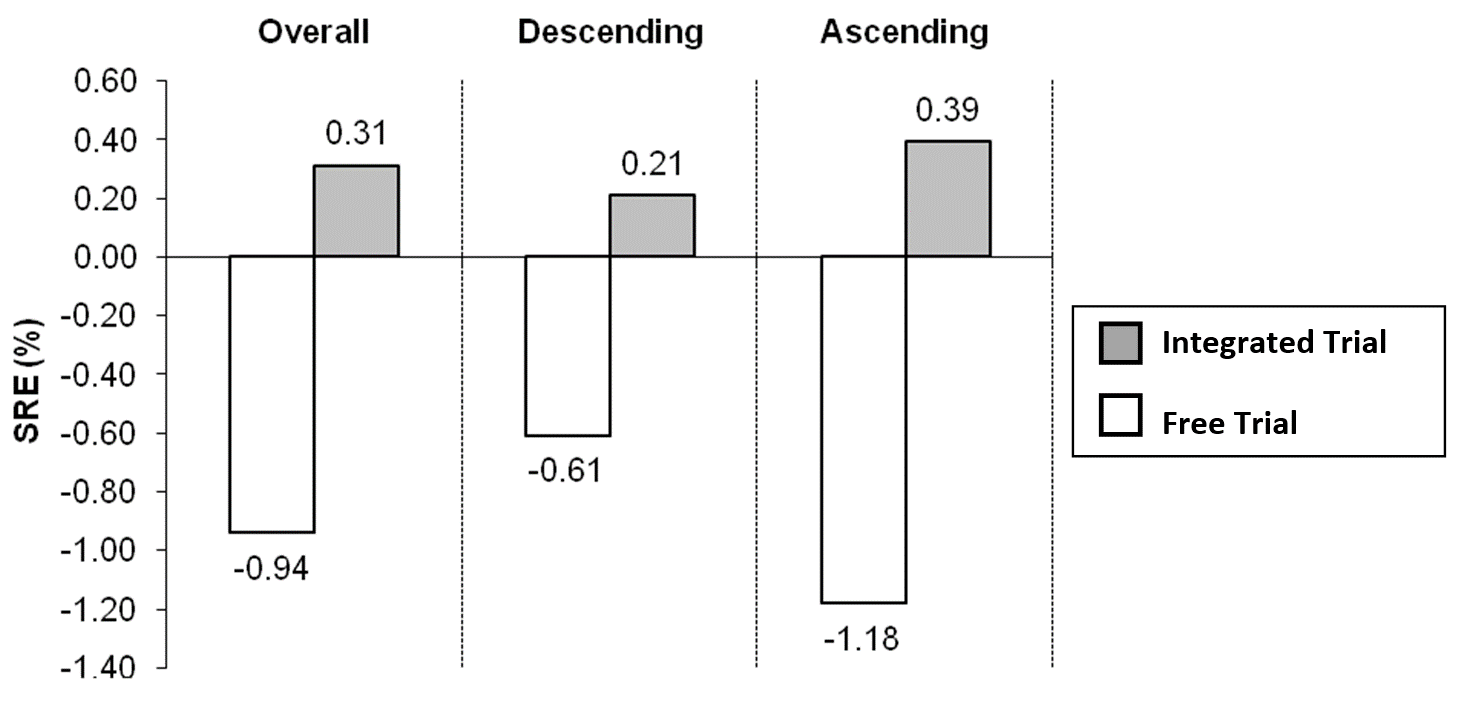

The analysis of trials regardless of movement direction showed a significant difference between trials (Z = 2.19, p = .02). It became evident that the participants exhibited in the Free Trial an undershoot pattern (-0.94%) in relation to target notes, while an overshoot pattern (0.31%) was observed in the Integrated Trial (Figure 4). The overshoot of 0.31% is not relevant in the perception of melodic intervals, because the just noticeable difference of consecutive tones is approximately 0.7% (nearly a tenth of a semitone, an irrelevant interval for the perception of human ears).

In the analysis of descending movements, the average of SRE between trials was marginally different (Z=1.85, p = 0.6) and an undershoot pattern was observed in the Free Trial condition, while a small magnitude overshoot pattern was observed in the Integrated Trial (Figure 5).

The same result was found in the analysis of ascending movements. The average of SRE between trials was marginally different (Z=1.85, p = 0.6) and an undershoot pattern was observed in the Free Trial condition, while a small magnitude overshoot pattern was observed in the Integrated Trial (Figure 5).

Figure 5 — Comparisons SRE (Signed Relative Error) between Integrated Trials (in grey) and Free Trials (in white) of double bassists trying to reach target notes in descending and ascending movements of the left hand.

The aim of this study was to investigate the double bass as far as the generation of undershoot and overshoot patterns and their relation with the sensorial information required in the performance. The starting point admitted that sensorial guidance (1) improves the accuracy and consistency of musical performance, (2) produces a less pronounced undershoot when compared to the no-guidance condition and (3) creates different undershoot/overshoot patterns in descending and ascending movements.

The results showed that the Integrated Trial (which combines vision, tact and ear) yielded greater precision and a tendency to a lower variability compared to the Free Trial (based on the ear only). These results indicate that the integration of visual and tactile cues increases the quality of intonation in an atonal, spatialized and interrupted sequence of pitches on the double bass, a sequence that comprises major intonation problems found in advanced repertories of the instrument. This fact may contradict the common belief that still prevails in conservative music pedagogy, which favors mainly the ear and do not consider vision and tact as relevant in movement regulation and precision. The findings also corroborate results of previous studies indicating the efficiency of visual and tactile sensorial sources in motor control not only in traditional laboratory aiming tasks (Elliott et al., 2014; Khan & Franks, 2003; Rabin & Gordon, 2004), but also in music performance (Lage et al., 2007). A possible explanation for the improved performance in the Integrated Trial (ear + vision + tact) is that tactile cues work as the first physical reference to the ongoing movement through the anchorage of the left forearm on the instrument, allowing the stabilization of the left shoulder and, consequently, providing an improved and stable movement control. Moreover, visual cues would direct focal vision towards the vicinity of a specific point on the fingerboard (Lage et al., 2007). Therefore, the internal processing seems to improve as far as accuracy and consistency are concerned. Nevertheless, this hypothesis claims for further research.

Regarding the overall analysis, the results showed that an overshoot pattern was produced in the Integrated Trial while an undershoot pattern was typical of the no-guidance trial (Free Trial). The quality of distance calibration in movement planning and online control is a plausible explanation for these results. The richer the structured visual information in a well-structured visual environment is, the better the system calibrates itself (Loftus, Murphy, McKenna, & Mon-Williams, 2004).

The uncertainty produced by the absence of systematic visual and tactile references in the double bass body may have led the participants to explore cognitive strategies responsible for undershoots in the Free Trial and for overshoots in the Integrated Trial. According to Imanaka and Abernethy (1992), undershoot and overshoot patterns can be linked to the specific strategy adopted in a specific task. It is also possible that the strategy may change as a consequence of an ongoing control process. In other words, the participants may have planned the movements to achieve the frequency below the target pitches to prevent the risk of overshooting and to reduce the probability of activating antagonistic muscles to reverse the movement (Elliott et al., 2014; Elliott et al., 2004; Lyons et al., 2006), what is considered a most embarrassing situation in music performance.

On the other hand, the use of both sensorial cues (vision and tact) may have led participants to achieve a higher degree of sureness and confidence to reach target pitches which, in terms of motor programming and use of feedback, produces an overshoot pattern. Even with this tendency to surpass the target pitch, a higher precision in reaching target pitches was observed in absolute RE measurements. An error in the overshoot pattern below 0.7% can be considered as a non-perceivable deviation, because the capacity of the human ear to distinguish successive and non-simultaneous tones is approximately a tenth of a semitone. Thus, bass players seem more confident to take more risks and make smaller mistakes when resorting to visual and tactile cues besides their ears.

The analysis of movement direction did not detect a well-defined undershoot/overshoot pattern between Free and Integrated Trials. However, the results showed a tendency (1) to achieve a frequency above the target pitch in both directions when sensorial guidance was available and (2) to achieve a frequency below the target pitch in the no-guidance condition. In descending movements (lower to higher registers) performed in the no-guidance condition, this tendency is in accordance with the search for minimum temporal and energetic costs to the system, also observed in other experimental motor behaviour findings (Elliott et al., 2004; Lyons et al., 2006) and in music research literature (Kantorski, 1986; Sogin, 1989). Surprisingly, this system strategy was not found in ascending movements (higher to lower registers) performed under the no-guidance condition. It was observed an overshoot pattern which produced frequencies below the target pitch. This contradicts the expectation of an undershoot pattern in this condition that would occur due to uncertainty of movement control in association with gravitational constraints.

This result allows one to speculate that when uncertainty (absence of systematic visual and tactile references in the instrument body) is present in ascending movements, the system opted for overriding temporal and energetic cost of overshooting (e.g., a longer distance travelled) in favour of achieving a frequency below the target pitch. In a descriptive analysis, the achieved frequency below the target pitch in this condition showed a higher level of directional error (-1,18%) when compared to the same condition in descending movements (-0.61). Possibly, the inherent search for minimization of temporal and energetic costs, which is often seen as beneficial to the system, could in fact need to be dismissed in specialized skills with very high demand of motor control (Oliveira, Elliott, & Goodman, 2005). This is the case for expert music performers in order to avoid the embarrassment of a feared major intonation defect on stage: a noticeable left-hand direction change that can be seen (in movement) and can be heard (in sound) by the audience in the performer's struggle to be in tune.

Further research needs to be carried out to analyse if this behaviour is driven by a perceptual factor in which playing out-of-tune below the target pitches is less uncomfortable than playing out-of-tune above the target pitches in situations performers feel less confident and not so sure about their intonation. Some research findings may support this supposition. Different melodic contours produce different outcomes in auditory processing. In animal models, it was observed that neurons in the auditory cortex of cats reacted differently to the same tone in inverse melodic contour (McKenna et al., 1989). Descending contours, for example, necessarily include shifts from higher frequencies to lower frequencies. The features of the auditory input may modulate motor behaviour, especially if one considers that the integration between auditory and motor systems is very well pronounced in trained musicians (Zatorre, Chen, & Penhune, 2007).

Concluding, the data presented here support the prediction that visual and tactile cues improve music performance accuracy on the double bass as far as intonation goes. Also, regardless of movement direction, the analysis of visual and tactile cues showed the production of undershoot patterns which may be connected to fear and, consequently, muscle contraction. The results regarding movement direction suggest that, in specific conditions of sensorial guidance, temporal and energetic mechanisms may be overruled by some demands of the task. This behaviour, which involves the participant's music embarrassing perception of bad intonation, is a matter still to be investigated. Finally, it is hoped that the results of this research will contribute to more inclusive and more democratic discussions in the international community of bassists, and to the diversity of ways of making music.

Applebaum, S., & Applebaum, S. (1973). The Way They Play (1 ed.). Neptune City, NJ: Paganiniana.

Avibigband. (2016). Fret markings on bass. Retrieved August 20, 2018, from http://goo.gl/V67CL7

Barber, B. (1990). Intonation: a sensory experience. American String Teachers Association, 40, 81-85.

Barber, B. (1991). Intonation: the major/minor difference. American String Teachers Association, 41, 82-86.

Bender, S., Resch, F., Weisbrod, M., & Oelkers-Ax, R. (2004). Specific task anticipation versus unspecific orienting reaction during early contingent negative variation. Clin Neurophysiol, 115(8), 1836-1845.

Borém, Fausto. (2011) Um sistema sensório-motor de controle da afinação no contrabaixo: contribuições interdisciplinares do tato e da visão na performance musical. Belo Horizonte: UFMG (Post Doctoral Dissertation).

Borém, Fausto, Lage, Guilherme, Vieira, Maurílio N., Barreiros, J. P. (2006). Uma perspectiva interdisciplinar da visão e do tato na afinação de instrumentos não-temperados In: Performance e interpretação musical: uma prática interdisciplinar.1 ed. Ed. Sônia Albano Lima. São Paulo: Musa Editora. p.80-101.

Brown, J. (2017). Just put these on. Retrieved August 7, 2018, from http://goo.gl/6m8E6M

Carlton, L. G., & Carlton, M. J. (1984). A note on constant error shifts in post-perturbation responses. J Mot Behav, 16(1), 84-96.

Elliott, D., Dutoy, C., Andrew, M., Burkitt, J. J., Grierson, L. E., Lyons, J. L., . . . Bennett, S. J. (2014). The influence of visual feedback and prior knowledge about feedback on vertical aiming strategies. J Mot Behav, 46(6), 433-443.

Elliott, D., Hansen, S., Mendoza, J., & Tremblay, L. (2004). Learning to optimize speed, accuracy, and energy expenditure: a framework for understanding speed-accuracy relations in goal-directed aiming. J Mot Behav, 36(3), 339-351.

Gabrielsson, A. (2003). Music Performance Research at the Millennium. Psychology of Music, 31(3), 221-272.

Galamian, Ivan. (1962). Principles of violin playing and teaching. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall.

Green, B. (1980). The Way they Play. In S. A. H. Roth (Ed.): Paganiniana.

Havas, K. (1979). The Twelve lesson Course in a New Approach to Violin Playing: Bosworth.

Havas, K. (1995). Stage fright; its causes and cure: with special reference to violin playing (10 ed.). London: Bosworth.

Imanaka, K. (1989). Effect of starting position on reproduction of movement: further evidence of interference between location and distance information. Percept Mot Skills, 68(2), 423-434.

Imanaka, K.; & Abernethy, B. (1992) Interference between location and distance information in motor short-term memory: the respective roles of direct kinesthetic signals and abstract codes. J Mot Behav, n.24, p.274-280.

Kantorski, V. J. (1986). String Instrument Intonation in Upper and Lower Registers: The Effects of Accompaniment. Journal of Research in Music Education, 34(3), 200-210.

Kenneson, C. (1974). A cellist's guide to the new approach (1 ed.). New York: Exposition Press of Florida.

Khan, M. A., & Franks, I. M. (2003). Online versus offline processing of visual feedback in the production of component submovements. J Mot Behav, 35(3), 285-295.

Lackner, J. R., & DiZio, P. (2000). Human orientation and movement control in weightless and artificial gravity environments. Exp Brain Res, 130(1), 2-26.

Lage, G. M., Borém, F., Vieira, M. N., Barreiros, J. P. (2007). Visual and tactile information in the double-bass intonation control. Motor Control, 11(2), 151-165.

Lage, G. M., Miranda, D. M., Romano-Silva, M. A., Campos, S. B., Albuquerque, M. R., Correa, H., & Malloy-Diniz, L. F. (2014). Association between the catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) Val158Met polymorphism and manual aiming control in healthy subjects. PLoS One, 9(6), e99698.

Loftus, A., Murphy, S., McKenna, I., & Mon-Williams, M. (2004). Reduced fields of view are neither necessary nor sufficient for distance underestimation but reduce precision and may cause calibration problems. Exp Brain Res, 158(3), 328-335.

Lyons, J., Hansen, S., Hurding, S., & Elliott, D. (2006). Optimizing rapid aiming behaviour: Movement kinematics depend on the cost of corrective modifications. Exp Brain Res, 174(1), 95-100.

Madsen, C. K. (1966). The Effect of Scale Direction on Pitch Acuity in Solo Vocal Performance. Journal of Research in Music Education, 14(4), 266-275.

McKenna, T. M., Weinberger, N. M., & Diamond, D. M. (1989). Responses of single auditory cortical neurons to tone sequences. Brain Res, 481(1), 142-153.

Medan, Y., Yair, E., & Chazan, D. (1991). Super resolution pitch determination of speech signals. IEEE Transactions on Signal Processing, 39(1), 40-48.

Morrison, S. J., & Fyk, J. (2002) Intonation. In The Science and psychology of music performance: creative strategies for teaching and learning. R. Parncutt and G. McPherson (eds.) New York: Oxford University Press. p.183-197.

Oliveira, F. T., Elliott, D., & Goodman, D. (2005). Energy-minimization bias: compensating for intrinsic influence of energy-minimization mechanisms. Motor Control, 9(1), 101-114.

Proteau, L., & Isabelle, G. (2002). On the role of visual afferent information for the control of aiming movements toward targets of different sizes. J Mot Behav, 34(4), 367-384.

Rabin, E., & Gordon, A. M. (2004). Tactile feedback contributes to consistency of finger movements during typing. Exp Brain Res, 155(3), 362-369.

Roberts, J. W., Elliott, D., Lyons, J. L., Hayes, S. J., & Bennett, S. J. (2016). Common vs. independent limb control in sequential vertical aiming: The cost of potential errors during extensions and reversals. Acta Psychol (Amst), 163, 27-37.

Robinson, P. (1990). Double Bass and Electric Bass Guitar: The Twain Shall Meet. American String Teacher, 40(4), 86-90.

Rolland, P., & Mutschler, M. (1986). The Teaching of Action in String Playing. Boosey and Hawkes.

Sloboda, J. (1996). The acquisition of musical performance expertise: deconstructing the "talent" account of individual differences in musical expressivity. In K. A. Ericsson (Ed.), The road to excellence: the acquisition of expert performance in arts and sciences, sports and games (pp. 107-126). New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

Sogin, D. W. (1989). An Analysis of String Instrumentalists' Performed Intonational Adjustments Within an Ascending and Descending Pitch Set. Journal of Research in Music Education, 37(2), 104-111.

Starr, W., & Suzuki, S. (1976). The Suzuki violinist: A Guide for Teachers and Parents. Introduction by Shinichi Suzuki. Knoxville, TN: Kingston Ellis Press.

Welz, K. (2001). Shared experience. Double Bassist, 18, 29-48.

Yarbrough, C., & Ballard, D. L. (1990). The Effect of Accidentals, Scale Degrees, Direction, and Performer Opinions on Intonation. Update: Applications of Research in Music Education, 8(2), 19-22.

Zatorre, R. J., Chen, J. L., & Penhune, V. B. (2007). When the brain plays music: auditory-motor interactions in music perception and production. Nat Rev Neurosci, 8(7), 547-558.

Zwicker, E., & Fastl, H. (1990). Psychoacoustics: Facts and Models (2 ed.). Berlin: Springer-Verlag.

Fausto Borém

School of Music

Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Brazil

Guilherme Menezes Lage

School of Physical Education

Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Brazil

First Brazilian to earn a Doctorate on Double Bass, Fausto Borém is the leader, composer and arranger of "Musa Brasilis Ensemble". He has presented recitals and lectures at ISB Conventions since 1993 and in several festivals in Europe. In Brazil, he teaches Bachelor, Masters and Doctorate bass students at UFMG (Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais), where he developed the Music Graduate Program and Per Musi, a top indexed scholarly journal. He has won several awards in both double bass performance ("2009 Brazilian Diapason D'or" with the "Juiz de Fora International Baroque Orchestra"; "São Paulo City Orchestra Soloists", 2007; 1st Prize in the "Jan Fowler Competition", 1983; 2nd Prize in the "Brazilian National Strings Competition", 1982), teaching ("UGA Teaching Assistant Award", 1993) and scholarly writing (Grand Prize in the "2018 ISB Research Competition," Honor Prize in the "2016 ISB Research Competition"). He has accompanied international performers in both classical (Yo‐Yo Ma, Midori, Menahem Pressler, Yoel Levi, Fábio Mechetti, and Arnaldo Cohen) and popular scenes (Hermeto Pascoal, Egberto Gismonti, Henry Mancini, Bill Mays, Grupo UAKTI and Toninho Horta). He has recorded five CDs with the "Juiz de Fora International Baroque Orchestra" and one Cd with the "Amazonas Baroque Orchestra". He has published dozens of works for the double bass, including the restoration of the 1838 "Double bass" manuscript and three songs by Afro-Brazilian Lino José Nunes and the 1898 manuscript of "Impromptu" for bass and piano by Leopoldo Miguez.

Guilherme M. Lage, holds a PhD in Neuroscience from UFMG (Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais), Brazil, where he is Full Professor in the Department of Physical Education, where he teaches Bachelor, Masters and Doctorate students. His research focuses on the relationships between motor behavior and neurobiology and also several interdisciplinary studies involving Physical Education, Music, and Acoustics.

© 2003 - 2026 International Society of Bassists. All rights reserved.

Items appearing in the OJBR may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the International Society of Bassists, and advance notification of the editors of the OJBR.

Any redistributed form of items published in the OJBR must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in The Online Journal of Bass Research in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] in [MONTH/YEAR], and it is republished here with the written permission of the International Society of Bassists.

Libraries may archive issues of OJBR in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of the OJBR and the International Society of Bassists.

Citations to articles from OJBR should include the URL as found at the beginning of the article and the paragraph number; for example:

Volume 3

Alexandre Ritter, "Franco Petracchi and the Divertimento Concertante Per Contrabbasso E Orchestra by Nino Rota: A Successful Collaboration Between Composer And Performer" Online Journal of Bass Research 3 (2012), <http://www.ojbr.com/volume-3-number-1.asp>, par. 1.2.Volume 2

Shanon P. Zusman, "A Critical Review of Studies in Italian Sacred and Instrumental Music in the 17th Century by Stephen Bonta, Burlington, VT: Ashgate Publishing Co., 2003." Online Journal of Bass Research 2 (2004), <http://www.ojbr.com/volume-2-number-1.asp>, par. 1.2.Volume 1

Michael D. Greenberg, "Perfecting the Storm: The Rise of the Double Bass in France, 1701-1815," Online Journal of Bass Research 1 (2003) <http://www.ojbr.com/volume-1-complete.asp>, par. 1.2.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.