Abstract: The art of improvising fermata embellishments, including cadenzas and lead-ins, once flourished among concerto soloists in the late eighteenth century. The composer-performer-improvisers of this period learned the creative skills that they needed to invent music in real time as an essential part of their craft. Though period treatises on performance practice provide guidelines for fermata embellishments, they neglect to furnish example cadenzas from specific concertos. This article examines the creative practices behind sixteen cadenzas by Johannes Sperger (1750-1812) from the manuscripts of six of his eighteen concertos for the Viennese violone as well as Anton Zimmermann's Concerto No. 1 and Franz Anton Hoffmeister's Concerto No. 3. These creative practices include the use of recurring stock formulas across cadenzas, the quotation of themes, motives, and figurations from specific concertos, and multiple beginning, middle, or ending sections that create cadenzas with various permutations. As with Mozart's piano concerto cadenzas, Sperger's contrabass concerto cadenzas contain evidence of both compositional and improvisatory practices, demonstrating a range of historical tools that present-day soloists can adapt for their own use to learn the related processes of fully composing, partially sketching, and freely improvising cadenzas. This three-part article first deduces Sperger's principles of cadenza creation, then analyzes selected manuscript cadenzas by Sperger, and lastly explains strategies for creating new cadenzas. The appendices compile stock formulas from selected Allegro cadenzas in C or D major and Adagio cadenzas in G or A major with the goal of helping performers learn to compose or improvise new cadenzas.

For the curious soloist, concertos from the late eighteenth century offer an opportunity to explore the art of extemporization, the invention of music in real time.1 During this time period, soloists often improvised new cadenzas, lead-ins, and embellishments each time they performed a concerto.2 The cadenza at the close of most first, second, and some third movements allowed the soloist to meditate on the preceding music in an oneiric soliloquy rife with surprises for the audience.3 Shorter than cadenzas, lead-ins, also called Eingänge or Fermaten,4 could appear in any movement and consisted of nonthematic improvised passages marked by fermatas, thus giving the soloist opportunities to make asides to the audience, either at transitions to new sections or before thematic reprises, as in a rondo.5 When a previously heard theme returned, the soloist created variety by adding tasteful embellishments.6 The realization of these extemporized elements required the soloist to make creative decisions in performance. These improvisatory practices waned in the nineteenth century due to the changing status of professional musicians from artisans trained through apprenticeships in court orchestras with aristocratic patrons to conservatory-educated bourgeois artists who performed for paying audiences in public concerts.7

This tripartite article investigates a subset of the extant manuscript cadenzas for the contrabass concertos written by and for prolific composer and Viennese violone virtuoso Johannes Sperger (1750-1812),8 including nine Allegro cadenzas and seven Adagio cadenzas. The first part explains the stylistic rules behind Sperger's cadenzas, the second part analyzes selected manuscript cadenzas with annotated transcriptions, and the third part presents the concept of a cadenza network with multiple possible realizations as a pedagogical tool for teaching and learning the process of creating cadenzas.9 The appendices contain cadenza networks in Viennese tuning and fourths tuning that consist of excerpts from the cadenzas presented in this article. These excerpts may be recombined, altered, and/or embellished to compose new cadenzas, or internalized as a knowledge base of idiomatic stock figurations to draw from while improvising cadenzas. The goal of this research is to equip performers, teachers, and students with stylistic context and strategies for creating new cadenzas.

Sperger's cadenzas demonstrate one late-eighteenth century contrabass soloist's personal style and approach to creating improvisatory cadenzas. His practice of notating cadenzas with multiple beginnings, endings, or interchangeable options, the presence of several cadenzas for one movement, and stock formulas that appear in several cadenzas indicate his improvisatory approach to fermata embellishment. Moreover, the creative practices that Sperger employed in his cadenzas can guide modern performers who seek to create new cadenzas in his style.

Whereas historical treatises and modern scholarship focus on cadenzas for the fortepiano, violin, or winds, this article explores cadenzas for the Viennese violone, which Sperger labelled 'Contrabasso solo' in his concerto scores.10 In and around Vienna in the late eighteenth century, the five- or four-stringed violone with seven frets, tuned from top down A-F#-D-A-[F♮, E, or D], attained the status of a solo instrument in virtuoso concertos, sinfonie concertante, and obbligato arias.11 Other composers who featured the Viennese violone in solo works are Franz Joseph Haydn, Karl Ditters von Dittersdorf, Wenzel Pichl, Anton Zimmermann, Franz Anton Hoffmeister, Johann Baptiste Vanhal, and Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart.12

Previously published research on Sperger contains almost no discussion of the manuscript cadenzas, lead-ins, and embellishments for his contrabass concertos. Sperger scholars have focused on biography, organology, repertoire, playing technique, and performance practice;13 thus there are few references to improvising cadenzas. After noting Sperger's burgeoning thematic creativity in the first movement of his Concerto No. 15, Michinori Bunya mused: "Also noteworthy is the new theme in the development, which surprisingly appears only once — would Sperger have wanted to improvise on it in a cadenza?"14 This question likely stems from Sperger's frequent use of thematic quotation and embellishment in his cadenzas for concertos by Dittersdorf and Vanhal.15 By quoting themes, the performer renders homage to the composer. In Sperger's cadenzas for his own concertos, however, he quotes themes comparatively less often. Instead, the recurrence of stock formulas, idiomatic figurations, and harmonic schemas in his cadenzas demonstrates that he recycled material from earlier cadenzas in later cadenzas and occasionally borrowed non-thematic passagework from his cadenzas for concertos by his contemporaries to use in his cadenzas for his own concertos and vice versa. These allusions result in humorous intertextual references for audiences familiar with his concerto repertoire.

The purpose of this research into Sperger's cadenzas is to renew the practice of composing, improvising, and/or extemporizing cadenzas among performers today. This article undertakes an analytical study of a subset of Sperger's extant cadenzas with the goal of articulating guidelines and formulating strategies that will help readers to understand his performance practices. If needed, soloists can then pursue further training in improvisation or composition to learn to create new cadenzas, either following Sperger's lead or in their own style. Crafting cadenzas is one of many ways in which bassists may express themselves by engaging creatively with late-eighteenth century concertos. Sperger's manuscripts attest to other opportunities for creative self-expression by bass soloists, including improvising lead-ins at certain non-cadenza fermatas and extemporizing embellishments for the restatements of rondo themes. Improvising cadenzas also invites soloists to take risks, which is part of what makes performances of late-eighteenth century concertos so exciting for the modern listener. In this respect, the soloist's role in Sperger's concertos resembles that of a jazz musician, for whom playing an instrument, performing, composing, and improvising are overlapping and inseparable competencies.16 Ultimately, recovering the practice of improvising cadenzas gives soloists yet another avenue for showcasing their personal creativity, thereby engaging audiences with uniquely expressive performances.

Before learning to imitate the musical style of Sperger's cadenzas, it is necessary to deduce the principles that guided his creative decisions by analyzing the extant examples. In theorizing musical style, Leonard Meyer asserts that "all the traits (characteristic of some work or set of works) that can be described and counted are essentially symptoms of the presence of a set of interrelated constraints" and posits that "the theorist/style analyst must infer the nature of the constraints—the rules of the game—from the play of the game itself."17 The purpose of this section, therefore, is to propose several stylistic constraints that are evident in Sperger's cadenzas. Meyer delineates stylistic constraints into three hierarchical categories: transcultural laws that describe pattern perception, intercultural rules that determine musical syntax, and individual strategies that represent creative decisions. In any given cadenza, Sperger employs a subset of possible creative strategies that conform to the prevailing stylistic rules.

Part 1 of this article reverse-engineers these stylistic rules from the sources and proposes a set of generative criteria to model the creative decision-making processes behind Sperger's first- and second-movement cadenzas for his own concertos. These criteria include the four-part form, harmonic progressions, motivic development techniques, and thematic quotation strategies that determine the structure and content of his cadenzas. Part 2 analyzes these criteria in selected cadenzas and identifies the stock formulas, recurring figurations, and harmonic progressions listed in the Appendices, thereby showing the development of Sperger's cadenza style.

The cadenzas examined in this article correspond to fermata pairs in the closing ritornellos of first movements in sonata-ritornello form and in the codas of second movements in da capo aria form or Romance form in Sperger's contrabass concertos.18 Modern theorists have studied the cadential function that cadenzas fulfill as parenthetical insertions within concerto movements,19 basing their observations on treatises by Quantz, Türk, and Koch.20 Whereas these scholars took piano cadenzas by Mozart and Beethoven as their main models, this article analyzes Sperger's contrabass cadenzas as a separate set of examples that may imitate but do not necessarily match the harmonic scope, idiomatic figurations, or contrapuntal complexity of keyboard cadenzas.

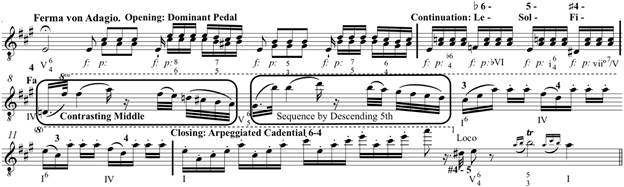

Eva and Paul Badura-Skoda have observed a tripartite structure in many of Mozart's first-movement cadenzas for his piano concertos with three sections: opening, middle, and closing.21 Robert Levin has proposed an alternative model that consists of an optional introduction, a first section that quotes from the first theme group, a second section that quotes from the second theme group, and a conclusion.22 In contrast, most of Sperger's cadenzas exhibit a tetrapartite structure in which thematic quotation, if present, most often occurs in the opening. Adapting from these Mozartian models, I have named the four sections in Sperger's cadenzas based on their rhetorical function: opening, continuation, contrasting middle, and closing. These labels reflect Sperger's frequent reliance on motivic development and iterative variations as generative strategies in the continuation, along with the change in register, motive, or rhythmic subdivision that demarcates the contrasting middle. These three models of cadenza form appear in Table 1.1.

Table 1.1. Three models of formal structure in cadenzas by Mozart and Sperger.

| Mozart: Badura-Skodas' Model | Mozart: Robert Levin's Model | Sperger: Four-Part Hybrid Model |

| Opening: virtuoso or thematic | Introduction: optional passagework | Opening: sometimes thematic |

| First section: first theme group | Continuation: developmental | |

| Middle: reminiscence theme | Second section: second theme group | Contrasting Middle: abrupt change |

| Closing: passagework before trill | Conclusion: closing flourish and trill | Closing: ascent to V64 and trill |

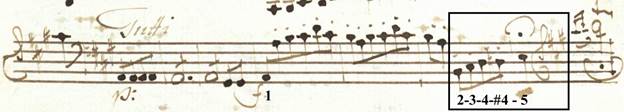

In keeping with Mozart's practices, Sperger's cadenzas elaborate the cadential progression V6453-I, while his lead-ins prolong V or V7.23 Sperger's cadenzas may delay the inevitable final trill and the expected resolution to the tonic with anticipatory predominant harmonies built upon chromatic neighbor tones to scale degree 5, including the secondary dominants V7/IV, V7/V, and vii°7/V. These progressions result in basslines that include scale degrees 3-4-#4-5, ♭7-6-♭6-5, #4-5-♭6-5, or ♭6-5-#4-5. This last chromatic encirclement of the dominant is called the le-sol-fi-sol schema.24 Upon arriving at a dominant pedal point, Sperger alternates between the cadential six-four chord and V7, with occasional detours to IV. Sometimes Sperger resolves V7/IV to a scalar outline of ii, ambiguously implying deceptive motion. In these instances, Sperger prioritizes resolving tendency tones like sevenths rather than explicitly playing roots.

A variety of stock formulas and recurring figurations appear in Sperger's cadenzas. Arpeggiated or scalar forms of the cadential six-four chord and V7 are ubiquitous in his cadenzas. Another common technique is the waveform scale, in which each quarter-note beat alternates between descending and ascending sixteenths, thereby outlining triads. Bariolage harmonic progressions, dominant pedal-point patterns, and double-stop scales in thirds appear in multiple cadenzas, some reproduced exactly, others with variations. Sperger also employs the rhythmic devices of diminution and augmentation to insert stock formulas from one cadenza into another.

Table 1.2 shows four strategies that Sperger employs to develop thematic fragments, motives, and figurations from the movement in his cadenzas. He transposes thematic fragments using the model-sequence technique to dissolve thematic quotations and to make transitions within the cadenza. In a strategy that I term the motivic-development schema, Sperger states, restates, and then develops a motive by spinning it out, either punctuating the end with a rest or transitioning directly into the next idea. In a related strategy that I call the triple-statement launch schema, Sperger repeats a bar-long dominant-pedal pattern three times before launching into another idea, often scalar figurations that ascend to the final arpeggiation of the cadential six-four chord in the high register. Though Sperger occasionally builds constructions resembling antecedent and consequent pairs that imply either half and authentic cadences or dominant-tonic alternation, his cadenzas rarely articulate formal cadences. Internal cadences in a cadenza are rare, since cadenzas normally generate suspense by delaying the resolution of a movement's final cadence.25 Whereas Mozart's piano cadenzas include homophonic textures and multi-voiced chords, Sperger favors monophonic textures, double-stops, or bariolage passages in his cadenzas.

Table 1.2. Motivic development devices in Sperger's cadenzas with examples labeled as Concerto.Movement.

| Motivic Development Device | Definition | Examples |

| Model-Sequence Technique | Transposed quote creates sequence | 2.I, 3.I, 11.I |

| Motivic-Development Schema | State, restate, then develop a motive | 2.I, 2.II, Z1.II, 7.I, 8.I, 8.II, 12.I, 13.I |

| Triple-Statement Launch Schema | State, restate, restate, launch or ascend | 2.I, 10.I, H3.II, 12.I, 12.II, 16.I |

| Antecedent-Consequent Pairs | Parallel phrases imply HC-IAC or V-I | 3.I, 8.II, 12.I |

Table 1.3 lists the diverse strategies that Sperger employs to quote themes in his cadenzas. As an opening or closing gambit,26 Sperger may begin or end a cadenza with a memorable thematic incipit that he develops using the model-sequence technique. Motivic citation refers to the quotation of a short musical motive, usually one that appears during the recapitulation or the transition to the cadenza.27 Varied recall occurs when Sperger quotes a previously heard theme with new variations. Sperger sometimes anticipates themes from the next movement or recollects themes from the previous movement. Sperger transposes themes originally heard in a non-tonic key into the tonic or places them over a dominant pedal. He occasionally transforms a theme's character from lyrical to dramatic by changing from the tonic major to the parallel minor key.

Table 1.3. Thematic quotation strategies in Sperger's cadenzas with examples labeled as Concerto.Movement.

| Thematic Quotation Strategy | Definition | Examples |

| Opening or Closing Gambit | Exact thematic quotation opens or closes the cadenza | 2.I, 2.II, 3.I, 3.II, 11.I |

| Motivic Citation | Use of a motive from the transition into the cadenza | 7.I, 8.I |

| Varied Recall | Quotation of theme or figuration with new variations | 3.I, 7.I, 13.I, 16.I |

| Anticipation/Recollection | Quoting material from next or previous movement | 3.II |

| Transposition | Secondary theme quoted in tonic key | 2.II |

| Transformation | Character change from major to minor or vice versa | 8.II, Z1.II, 12.I, 16.I |

The manuscripts in Part 2 contain evidence of Sperger's performance practices, which will form the basis of the discussion about learning to improvise cadenzas in Part 3. Sperger's cadenzas traverse the Viennese violone's four-octave range, employing harmonics and stopped notes in the highest octave and only one G# below the low A string. Sperger often notates several different embellishments for the same fermata in the solo part and/or on the cadenza page, which provides evidence of the evolution of his musical ideas. Sperger uses notations that resemble Coda and Dal Segno symbols to show corrections, insertions, and multiple beginnings or endings in his cadenzas. Sperger's use of false ending trills in cadenzas that contain a second iteration of the four-part form recalls Danuta Mirka's conception of the cadenza as a witty game between the soloist and the orchestra.28 These double cadenzas show Sperger subverting gestures that usually cue the ensemble to reenter. The next section analyzes selected cadenzas from Sperger's estate.

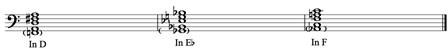

The manuscripts presented in this section are located at the Landesbibliothek Mecklenburg-Vorpommern Günther Uecker in Schwerin, Germany (hereafter D-SWI) and are labeled with the prefix 'Mus' and the shelf number. The numbering of Sperger's eighteen contrabass concertos follows the order and chronology given in Adolf Meier's catalogue.29 In the transcriptions of Sperger's manuscript cadenzas, the bass part is notated in the register in which it appears in the original text, which Sperger notated in treble clef an octave higher than modern practice. In the transcriptions, treble clefs with an octava bassa sign are a reminder to readers that the sounding pitch is two octaves lower than the written pitch. The transposable tuning of the fretted four- or five-string Viennese violone, labeled 'Contrabasso solo' in Sperger's concerto scores, appears in Example 2.2 with a picture in Example 2.1. For all but three of the concertos with cadenzas presented here, Sperger tuned the solo contrabass a half-step higher so that it functioned as a transposing instrument, with the solo part notated in the written keys of D and A rather than the sounding keys of E♭ and B♭.

Example 2.1. Viennese Violone in the Berlin Philharmonic Instrument Museum

Example 2.2. Transposable 4- or 5-string Viennese Tunings in D, E♭ and F.

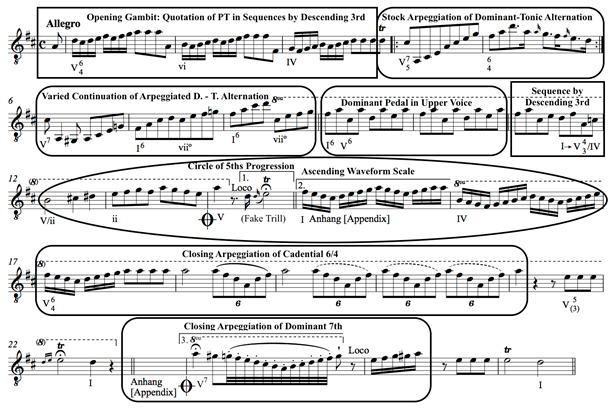

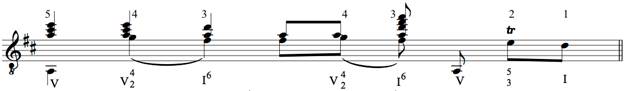

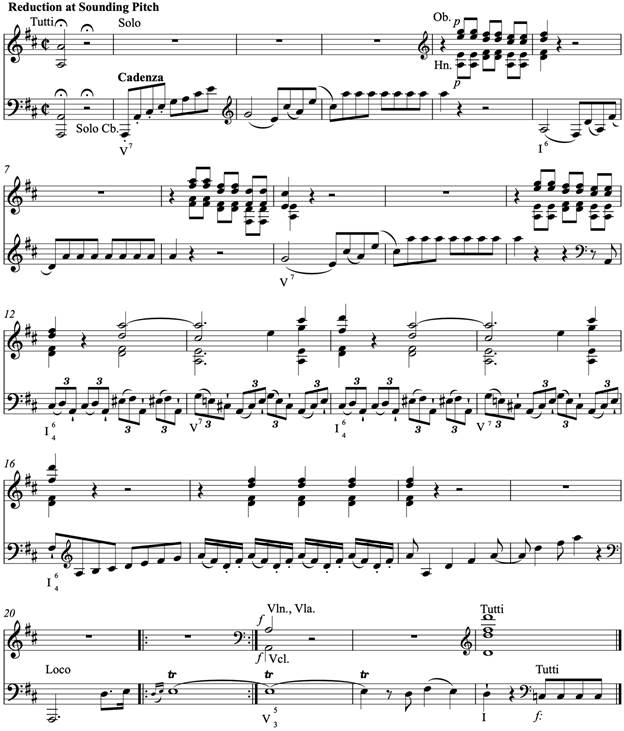

The first-movement cadenza for Concerto No. 2 contains three possible options of different durations. Shown in Examples 2.3 and 2.4, this cadenza contains both a specific thematic quotation from the movement and generic figurations like the ascending waveform scale that reappear in later cadenzas. As his opening gambit, Sperger quotes one bar of the primary theme and repeats it twice in sequence by descending third using the model-sequence technique. This sequence echoes the I-vi-IV progression in the tutti transition before the cadenza fermatas. In the continuation, Sperger implements the motivic-development schema with an arpeggiation of V7564 in bars 4-5, a stock formula that reappears with slight variations in the opening of the third cadenza on the cadenza page for Concerto No. 12 in Example 2.34 and in Sperger's cadenza for the first movement of Vanhal's concerto. The development of the V7564 arpeggiation rises to the high register, where Sperger employs the motivic-development schema again to spin out an upper-voice dominant pedal pattern. A feint via V43/IV moves to V/ii, before circle-of-fifths motion through ii and V leads to the first ending trill. This first version is the shortest option.

In the second version, this now false first ending trill ushers in an ascending waveform scale that peaks with four arpeggiations of the cadential six-four chord before a second closing trill. The third version continues from the high A before the first trill to a scale outlining V7, although the same continuation could be inserted after the high A in the penultimate bar of the second version, thus connecting all three versions in the order Sperger wrote them. The roman numeral analysis below the reduction in Example 2.5 shows Sperger's use of sequential transposition by descending third in bars 1-3 and bar 11, a dominant pedal point in the upper voice in bars 9-10, and a five-bar circle of fifths progression in bars 12-16 that spans the false first ending trill.

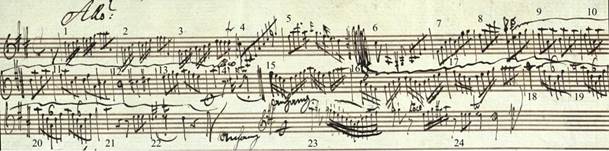

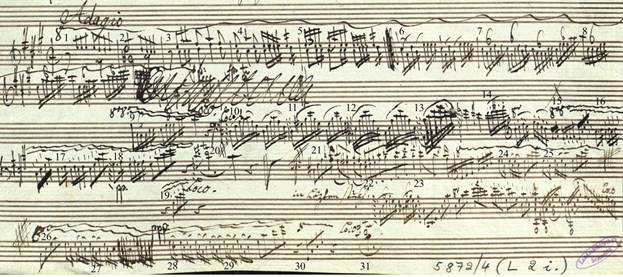

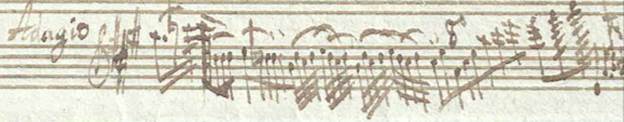

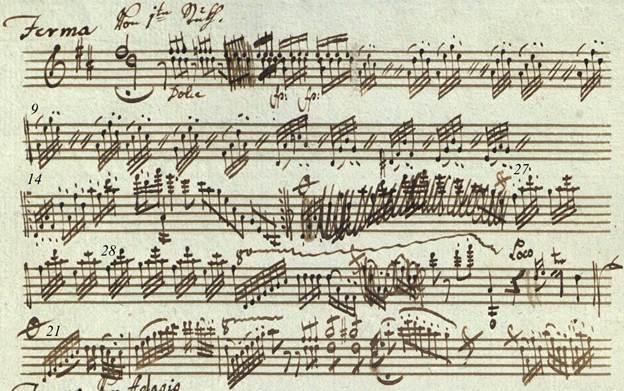

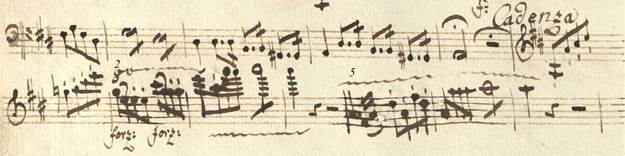

Example 2.3. Sperger, cadenza for I. Allegro moderato from Concerto No. 2 (m. 192), Mus 5872/4, L 2i.

Example 2.4. Transcription and harmonic analysis of cadenza for I. Allegro moderato from Concerto No. 2.

Example 2.5. Harmonic reduction of cadenza for I. Allegro moderato from Concerto No. 2.

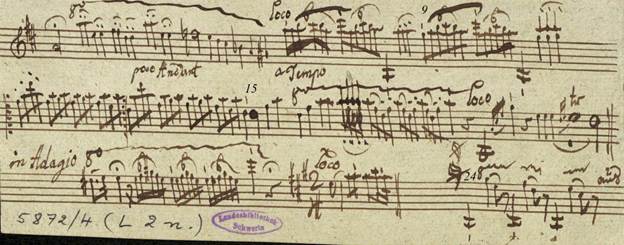

The three options on this cadenza page provide a glimpse into Sperger's creative process. There are scratched-out notes between bars 6 and 7. The bar line after the first ending trill with fermata resembles a final bar line, while the downbeat of bar 15 appears to have started as a D before Sperger altered it to F♯. Sperger labels each of the alternate endings Anhang [Appendix]. The first ending option notably fails to reiterate the cadential six-four chord before the trill, an omission that Sperger corrects in the second ending but not in the third, which contains a scalar outline of V7. The disposition of the three options shows the order in which Sperger notated them, generating alternative endings from his reservoir of idiomatic stock formulas perhaps because he deemed the first option to be too short, determined that the second option was too long, and then compromised with the third. As the longest of the three, the second option best reflects the archetypal four-part form of Sperger's cadenzas, with the high-register dominant pedal as the contrasting middle and the waveform scale as the start of the closing section.

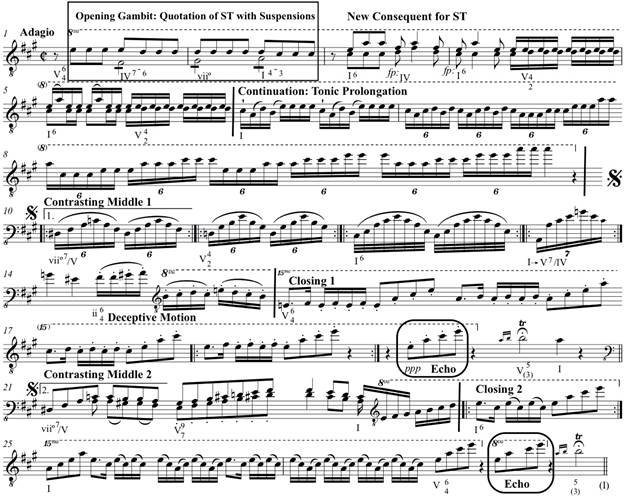

The second-movement cadenza for Sperger's Concerto No. 2 begins with an opening gambit by quoting a double-stop progression with suspensions from the secondary theme group, as shown in the top staff of Example 2.6. This quotation is a unique instance of linear voice-leading in the middle register. The middle staff shows the secondary theme where it first appears in the movement with its original bassline, resulting in a different three-voiced harmonic progression.

Example 2.6. Sperger, II. Cantabile from Concerto No. 2, Mus 5177/6 solo part, p. 11, mm. 62-65.31

As shown in Examples 2.7 and 2.8, the cadenza diverges from the quoted theme in the middle of the third bar, moves to the subdominant (I6-IV), and then alternates between tonic and dominant (I6-V42) before arpeggiating the tonic in sextuplets. After this high point, the cadenza diverges into two options for the contrasting middle section: an arpeggiated progression with a chromatically descending bassline or a double-stop passage. In the reduction in Example 2.9, the first ending progression in the top staff implies deceptive motion, with V7/IV resolving ambiguously to a scalar outline of ii64, while the second ending progression in the bottom staff arpeggiates vii°7/V before implying V97 with a double-stop scale in thirds. Both closing sections conclude the cadenza with arpeggiations of the tonic in successively higher inversions with an echo effect before the final trill. This echo results from pp dynamic markings in the first ending and a restatement of the arpeggio figuration one octave lower in the second ending. This cadenza shows Sperger's ability to craft endings with different figurations and harmonic trajectories.

Example 2.7. Sperger, Cadenza Network for II. Cantabile from Concerto No. 2 (m. 88), Mus 5872/4, L 2i.

Example 2.8. Transcription and Harmonic Analysis of Cadenza Network for II. Adagio from Concerto No. 2.

Example 2.9. Harmonic Reduction of Cadenza Network for II. Adagio from Concerto No. 2.

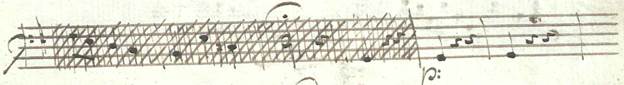

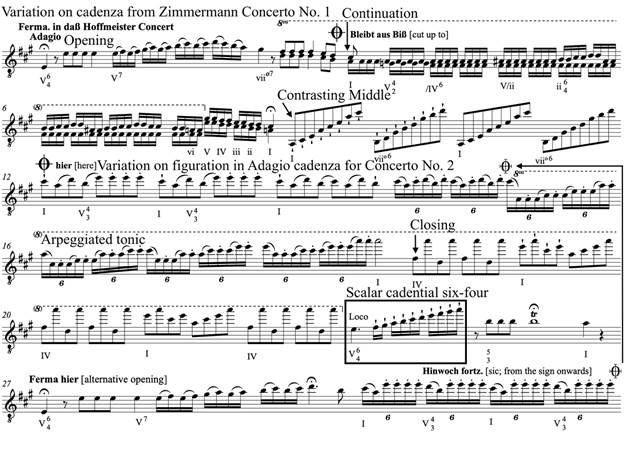

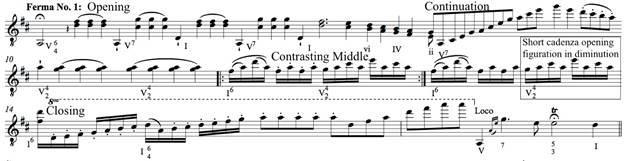

Anton Zimmermann (1741-1781), concertmaster of the Preßburg court orchestra where Sperger worked from 1777 to 1783, composed his first contrabass concerto for Sperger and his second for their colleague Josef Kämpfer (1737-after 1797).32 Sperger's estate holds the score and parts for the first concerto, including an unnumbered page in the solo part with three cadenzas on the front and a score fragment from another concerto on the back.33 Radoslav Šašina and Edicson Ruiz include the Allegro cadenza on this insert in their recordings of this concerto, but they follow Sperger's cut omitting the cadenza from the Andante in Example 2.10.34 This Andante is in G major, but the insert contains two Adagio cadenzas in A major, indicating that Sperger probably composed the cadenzas on the insert for another concerto.35 Sperger may have inserted this cadenza page into the solo part of Zimmermann's first concerto because the Allegro cadenza fit the character of the first movement; this suggests that Sperger transferred cadenza pages between concertos, with their current placement linked to the last time Sperger used them.

Example 2.10. Sperger, Cut in II. Andante from Zimmermann's Concerto No. 1, Mus 5817 solo part, p. 11.

The short Adagio cadenza from this insert appears in Examples 2.11, 2.12, and 2.13, while the long Adagio cadenza appears in Examples 2.14, 2.15, and 2.16. The short cadenza begins with vii°7/V, a harmony that figures prominently in the Allegro cadenza for Concerto No. 736 and opens the short Adagio cadenza for Concerto No. 8 in Example 2.25. The thirty-second note pattern in the short cadenza is a stock figuration that recurs in Sperger's Finale cadenza for Vanhal's Concerto.37 The long cadenza's opening outline of V7 returns in the cadenza in Example 2.44 with turns instead of grace notes. The continuation of the second cadenza features the open F♯ string in a pedal point on V/ii that reappears in the cadenza in Example 2.31, while the contrasting middle is a bariolage progression in the parallel minor with a sol-le-sol-fi-sol or 5-♭6-5-♯4-5 bassline. The closing tonicizes IV with a variant of the chromatic neighbor tone figuration that ends the Allegro cadenza for Sperger's Concerto No. 7 in A major (1781).

Example 2.11. Sperger, Short Adagio cadenza on insert in Zimmermann Concerto No. 1, Mus 5817 solo part.

Example 2.12. Sperger, Short Adagio cadenza on insert in Zimmermann Concerto No. 1, Mus 5817 solo part.

Example 2.13. Reduction of Short Adagio cadenza from Zimmermann Concerto No. 1, Mus 5817 solo part.

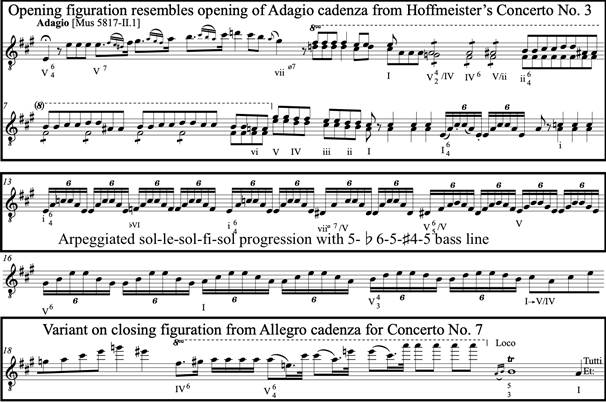

Example 2.14. Sperger, Long Adagio cadenza on insert in Zimmermann Concerto No. 1, Mus 5817 solo part.

Example 2.15. Sperger, Long Adagio cadenza on insert in Zimmermann Concerto No. 1, Mus 5817 solo part.

Example 2.16. Reduction of Long Adagio cadenza from Zimmermann Concerto No. 1, Mus 5817 solo part.

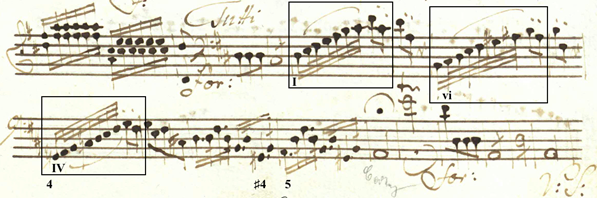

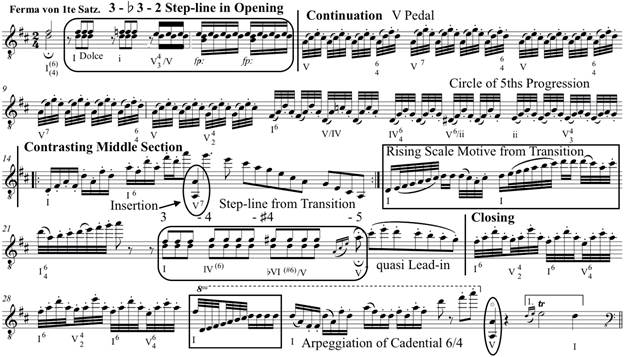

The first movement cadenza for Concerto No. 8 occurs after a ten-bar tutti transition containing a rising scale motive repeated in sequence by descending third, as shown with boxes in Example 2.17. The following bassline contains a step-line from scale degrees 4-♯4-5. In two examples of motivic citation, the rising scale motive and the 4-♯4-5 step-line appear in Sperger's cadenza for this movement, but the sequence by descending third is conspicuously absent.

Example 2.17. Sperger, pre-cadenza tutti in I. Allegro majestoso in Concerto No. 8, Mus 5177/4 solo pt., p. 9.

The Allegro cadenza from Concerto No. 8 in Example 2.18 opens with a descending chromatic step-line (3-♭3-2) over a tonic pedal that continues with a virtuosic bariolage passage over a dominant pedal. Sperger departs from the dominant pedal with a three-voice progression in the low register, where the frets of the Viennese violone render triadic patterns idiomatic. The ensuing repeated stock arpeggiation of I and V7 in the contrasting middle section contains a virtuosic leap down to an octave double-stop on A. Judging from the note spacing in the first iteration and the absence of the double-stop from the scribbled-out second iteration, Sperger evidently added the low double-stop after creating the initial version. This added virtuosity capitalizes on the range of the bass for comic effect while also furnishing a sonorous dominant pedal tone beneath the arching arpeggiated figuration, thereby sustaining the harmonic tension.

In this cadenza, Sperger uses symbols not to show alternative options but rather to replace erased sections in the body of the cadenza with new material from the bottom staff of the manuscript shown in Example 2.18. The first insertion contains two repetitions of a decorated version of the rising scale motive from the tutti transition, followed by the scale degree (3)-4-♯4-5 step-line from the transition in double-stops over a tonic pedal leading to a fermata on V. A group of seven eighth notes leads to a new figuration made up of parallel sixths oscillating around a dominant pedal in the middle voice, signaling the start of the closing section. The rising scale motive makes one last appearance before the closing arpeggiation of the cadential six-four chord, a low double-stop on the dominant, and the ending trill. Like the first movement cadenzas from the solo part of Concerto No. 12 in Example 2.34, this cadenza has an engaging narrative structure, alternating between dolce lyricism and dramatic virtuosity while juxtaposing the ethereal flageolet tones of high harmonics with the earthy depths of low multiple-stops. The second ending shows a chromatic ascent to a trill that appears at the bottom of this cadenza page. The slurs in Example 2.20 show melodic step-lines and conjunct motion in the bassline of this cadenza, which exemplifies several of Sperger's idiomatic figurations for the Viennese violone.

Example 2.18. Sperger, cadenza for I. Allegro majestoso from Concerto No. 8, Mus 5872/4, L 3b.

Example 2.19. Transcription of cadenza for I. Allegro majestoso from Concerto No. 8, Mus 5872/4, L 3b.

Example 2.20. Harmonic reduction of cadenza for I. Allegro majestoso in Concerto No. 8, Mus 5872/4, L 3b.

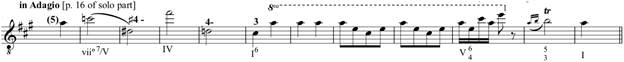

The cadenza fermata in the Andante poco Adagio from Concerto No. 8 follows a six-bar tutti transition ending with scale degrees 2-3-4-♯4-5 in the bass line, as shown in Example 2.21. In his two cadenzas for this movement, Sperger uses descending chromatic bass lines that refute this ascent. After dramatically arriving at the fermata, the long cadenza in Examples 2.22 and 2.23 begins with double-stop figurations over a dominant pedal before embarking on a le-sol-fi-fa progression that descends unexpectedly through scale degrees ♭6-5-♯4 to ♮4, not 5. Marked by a two-octave leap into the upper register, the contrasting middle section contains a sequence by descending fifth followed by alternation from I6 to IV with scale degrees 3 and 4 in the bass. After the closing arpeggiates V64, scale degrees ♯4-5 reappear, resolving the harmonic tension.

The bass line of Sperger's short cadenza for this movement also descends through scale degrees 5-♯4-♮4-3, reversing the ascent to the fermata before arpeggiating the cadential six-four chord. The slurs below the reductions in Examples 2.24 and 2.27 show the chromatic bass lines in both cadenzas. The first and second movement cadenzas for Concerto No. 8 show Sperger's use of conjunct chromatic motion in the melody and bassline to imply progressions that depart from and return to V64 or V7, creating an arc of tension and release within each cadenza.

Example 2.21. Pre-cadenza tutti in II. Andante poco Adagio from Concerto No. 8, Mus 5177/4 solo part, p. 9.

Example 2.22. Sperger, long cadenza for II. Andante poco Adagio from Concerto No. 8, Mus 5872/4, L 3b.

Example 2.23. Transcription, long cadenza for Andante poco Adagio from Concerto No. 8, Mus 5872/4, L 3b.

Example 2.24. Reduction of long cadenza for II. Andante poco Adagio from Concerto No. 8.

Example 2.25. Sperger, short cadenza for Andante poco Adagio, Concerto No. 8, Mus 5177/4 solo part, p. 16.

Example 2.26. Transcription of short cadenza for II. Andante poco Adagio from Concerto No. 8.

Example 2.27. Harmonic reduction of short cadenza for II. Andante poco Adagio from Concerto No. 8.

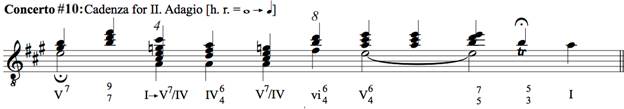

The first-movement cadenza for Concerto No. 10 in Example 2.28 and 2.29 consists of figurations that reappear with variations in the cadenzas for Concertos Nos. 12 and 16; this attests to Sperger's iterative embellishment of stock formulas. The opening sextuplet gestures and the continuation double-stops combine to create the opening of the cadenza for No. 16. The implied triple meter in the opening section of the cadenza for No. 10 creates metric ambiguity that resolves only after the first set of double-stops returns to cut time. The alternation between scale degrees 4 and 3 (G and F♯) in the lower voice of the double-stops presages similar voice-leading in passagework in the cadenzas for No. 12. The leaps between registers in this continuation exemplify Sperger's use of call and response to imply different characters. The sudden change to sixteenth notes in bar 9 signals the contrasting middle, which leads to the closing ascent. The dominant pedal pattern in the contrasting middle, the closing waveform scale interrupted by a repeated scale degree 5, and the scalar V64 each return in different cadenzas for Concerto No. 12. The crossed-out flourish and trill in the first ending contain scale degrees 1-2-3-2-1, while the second ending outlines V7, creating a 4-3-2-1 step-line. The reduction in Example 2.30 shows that this cadenza is primarily a prolonged dominant pedal point.

Example 2.28. Sperger, cadenza for I. Moderato from Concerto No. 10, Mus 5177/1 solo part, p. 18.

Example 2.29. Transcription of cadenza for I. Moderato from Concerto No. 10, Mus 5177/1 solo part, p. 18.

Example 2.30. Harmonic reduction of cadenza for I. Moderato from Concerto No. 10, Mus 5177/1, p. 18.

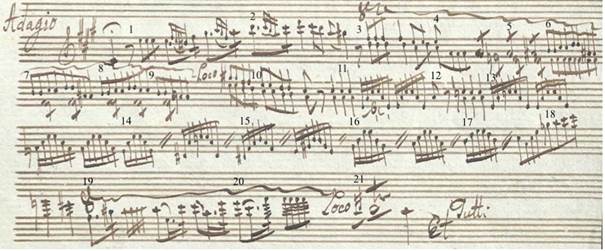

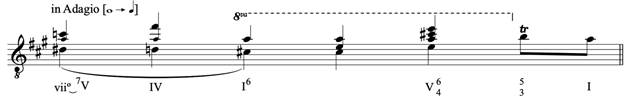

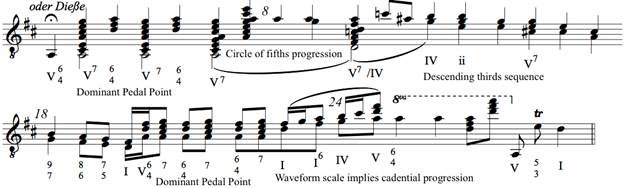

Of Franz Anton Hoffmeister's three contrabass concertos, Concerto No. 3 is the only one in Sperger's estate and the only one with his cadenzas.38 In his cadenza page for this concerto, Sperger uses symbols along with instructions to create a network of several possible Adagio cadenzas, given in Examples 2.31 and 2.32 with a reduction in 2.33. These options result from two possible openings and an internal cut. Taking the cut from bar 46 to bar 54 or the alternative opening in bar 69 approximately halves the total length. Sperger also scribbled out the original ending and replaced it with a longer alternative. This evidence suggests that Sperger started this virtuosic cadenza with an abundance of ideas that he later abridged to meet his expectations for cadenza length during his concert tours in search of employment from 1786 to 1789.39

Both openings for the cadenza in Example 2.31 are variants on the scalar outline of V7 in the long Adagio cadenza from Zimmermann's Concerto No. 1 in Example 2.14. The original continuation of the Hoffmeister Adagio cadenza is a sixteenth-note variation of the pedal point on V/ii in eighth notes from Example 2.14. The two-octave arpeggios of I and vii°6 in the contrasting middle are unique to this cadenza, but the ensuing tonic prolongation is in the Adagio cadenza for Sperger's Concerto No. 2 in Example 2.7. After these sextuplet tonic arpeggios, Sperger closes with a leaping figuration in harmonics that teasingly alternates between I and IV before moving to a scalar outline of V64. After a sextuplet variation on the tonic prolongation figure, the alternative opening reconnects at the tonic arpeggiation. This Adagio cadenza draws on figurations from earlier cadenzas and highlights Sperger's use of stock formulas to invent new cadenzas. In its original form, this Adagio cadenza is the longest of its kind in Sperger's output.

Example 2.31. Sperger, Cadenza for II. Adagio from Hoffmeister's Concerto No. 3, Mus 2850 solo part insert.

Example 2.32. Sperger, Cadenza for II. Adagio from Hoffmeister's Concerto No. 3, Mus 2850 solo part insert.

Example 2.33. Harmonic reduction of cadenza for II. Adagio from Hoffmeister's Concerto No. 3, Mus 2850.

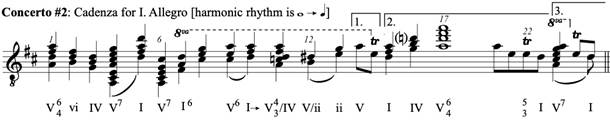

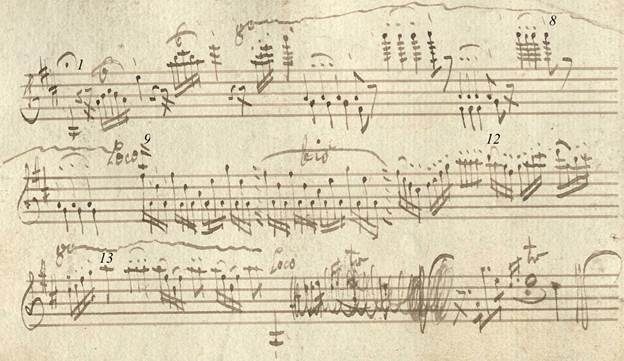

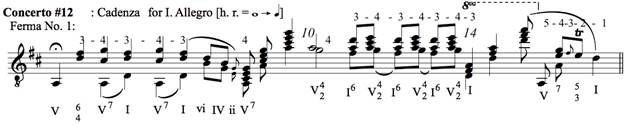

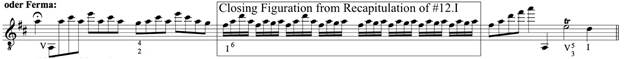

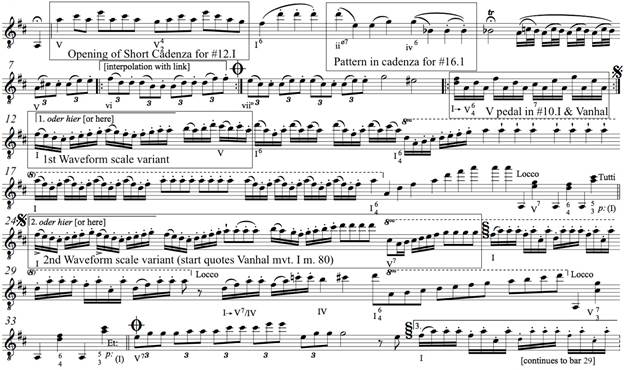

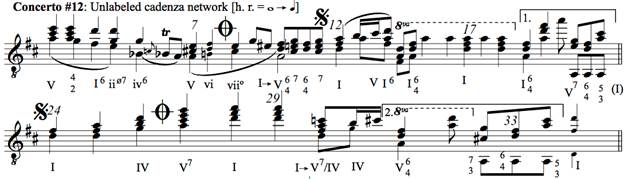

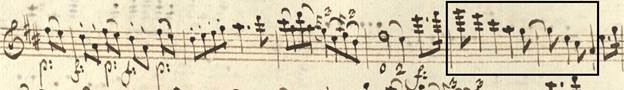

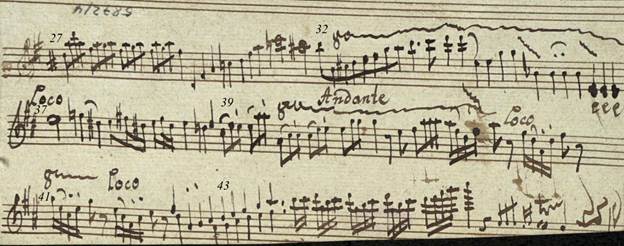

The solo part for Sperger's Concerto No. 12 includes a double-sided page with five cadenzas. The front holds the three first-movement cadenzas in Example 2.34 and the second-movement cadenza in Example 2.44, while the back holds the first-movement cadenza network in Example 2.41. These cadenzas show several improvisatory aspects of Sperger's creative process. Sperger employs recurring stock formulas in multiple cadenzas, either interwoven with quotes from the concerto or varied with embellishments. In the cadenza network, he uses symbols that map out several possible realizations given the same start and endpoints. This page from the solo part of Concerto No. 12 may indicate that Sperger drafted several cadenzas for one concerto and/or that he collected cadenzas for several concertos on one page; the metric mismatch between the triple-meter Adagio cadenza and the duple-meter Andante in Concerto No. 12 supports the latter.

One of the first-movement cadenzas and the second-movement cadenza contain stock figurations that also appear in the corresponding cadenzas for the Vanhal concerto (c.1786-1789, Vienna).40 This time period encompasses the completion dates of Sperger's Concertos No. 9 (1785-1786, Kofidisch and 1786-1787, Vienna) and No. 10 (1787, Berlin).41 The starting half notes, ending trills, and quadruple meter in two of the first-page cadenzas match the common-time first movement of Concerto No. 9.42 In addition, the non-trill ending of the cadenza network matches the half rest under the second cadenza fermata in the solo part of Concerto No. 15 (1796).43 This collection may therefore contain the accumulation of Sperger's improvisatory ideas for several of the concertos that he composed in the years after Concerto No. 8 (1783) and before Concerto No. 16 (1797), which each have a page with embellishments for all fermatas.

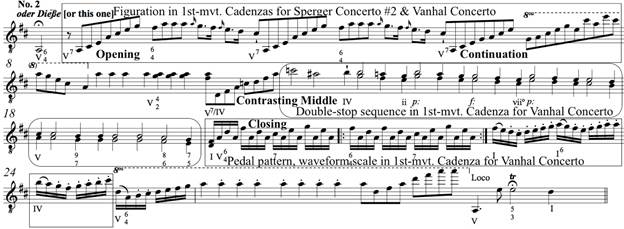

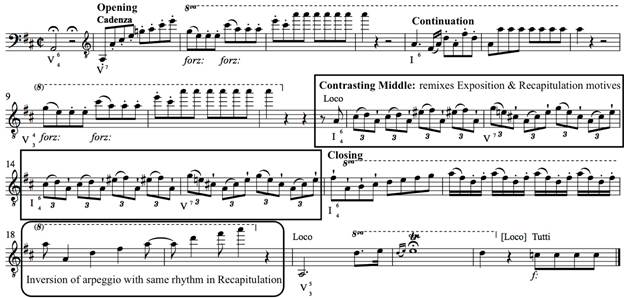

Of the three first-movement cadenzas in D major in Example 2.34, only the short middle cadenza quotes directly from the Allegro moderato in Concerto No. 12. Sperger labels the other two longer cadenzas No. 1 and No. 2, respectively, with oder [or] and oder Dieße [or this one] linking the three cadenzas. This disposition presents each cadenza as an alternative to the others, supported by contrasts in content and differences in length that suggest that each cadenza could be for separate performances of the same concerto or even for a series of several concertos. The distinctive elements of the two longer cadenzas fit into the four-part form of Sperger's cadenzas.

Example 2.34. Sperger, Cadenzas for I. Allegro moderato from Concerto No. 12, Mus 5176/7 solo part, p. 17.

The opening of the first cadenza in Example 2.35 employs double-stops to alternate between V64 and V7, while the continuation arpeggiates V7 in an arcing gesture. The contrasting middle section begins with two beats of closing figuration from the recapitulation of the first movement of Concerto No. 12, but then diverges into the opening figuration from the short cadenza and the cadenza network in diminution. The closing section ascends through scalar and arpeggiated forms of V64. The Arabic numerals above the staff in the reduction in Example 2.36 show the alternation between scale degrees 3 and 4 (F♯ and G) in the upper or lower voice throughout.

Example 2.35. Sperger, 1st Cadenza for I. Allegro moderato in Concerto No. 12, Mus 5176/7 solo part, p. 17.

Example 2.36. Harmonic Reduction of 1st Cadenza for I. Allegro moderato in Concerto No. 12.

The short cadenza in Example 2.37 and the cadenza network in Example 2.42 start with fermatas over quarter-note A's in two different octaves, rather than the half-note A under the first fermata in the other cadenzas in Example 2.34. Whereas a half-note low A is usual for Sperger's cadenza fermatas in common time or alla breve first movements, these quarter-note A's reveal an inconsistency between the fermata notes in the solo part and in the cadenza page. This short cadenza reprises closing theme figuration from the first movement of Concerto No. 12 that oscillates between scale degrees 3 and 4, prolonging the 5-4-3-2-1 step-line in Example 2.38.

Example 2.37. Sperger, Short Cadenza for I. Allegro moderato in Concerto No. 12, Mus 5176/7 solo pt., p. 17.

Example 2.38. Harmonic Reduction of Short Cadenza for I. Allegro moderato from Concerto No. 12.

The boxes in Example 2.39 show that the second cadenza for Concerto No. 12 mainly consists of figuration that also appears in the first movement cadenzas for Sperger's Concerto No. 2 and Vanhal's Concerto. The opening four bars and the waveform scale differ from the versions in the cadenza for Concerto No. 2, while the double-stop sequence in the contrasting middle has note values that are twice the length of those in the cadenza for Vanhal's concerto. The subtle differences between these similar passages in three cadenzas evince that Sperger varied stock formulas when creating generic cadenza content, to which he added quotations from specific concertos. The cadenza in Example 2.39 resembles a draft or a reworking of the Vanhal cadenza. The reduction in Example 2.40 shows Sperger's elision of a circle of fifths progression in the continuation with a descending thirds sequence in the contrasting middle.

Example 2.39. Sperger, 2nd Cadenza for I. Allegro moderato in Concerto No. 12, Mus 5176/7 solo part, p. 17.

Example 2.40. Harmonic Reduction of 2nd Cadenza for I. Allegro moderato from Concerto No. 12.

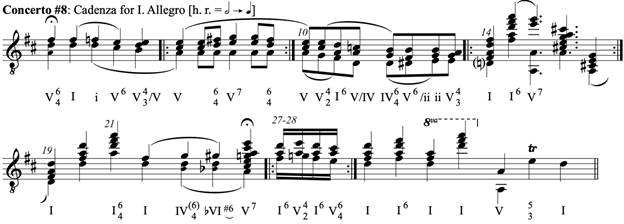

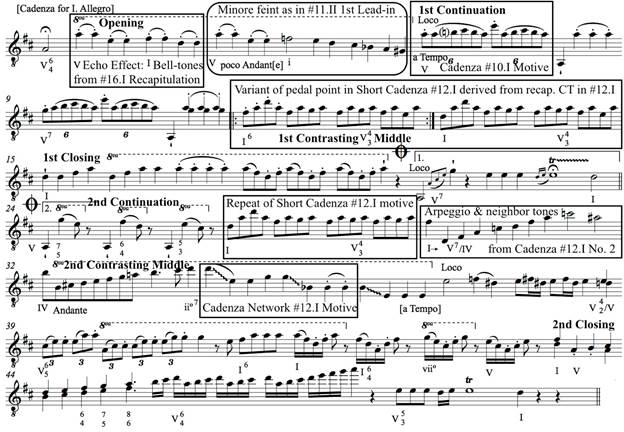

The cadenza network in Examples 2.41 and 2.42 is unique among Sperger's cadenzas for its use of symbols to notate three possible cadenzas with the same beginning and ending. This practice anticipates Robert Levin's use of numbered options in modular cadenzas for Mozart's Violin Concertos.44 This cadenza network shares its point of departure with the short cadenza for Concerto No. 12, but the ensuing leaping minore pattern reappears an octave higher in the cadenza for Concerto No. 16. The dominant pedal pattern in bar 11, meanwhile, also appears in the first-movement cadenzas for Concerto No. 10 and Vanhal's Concerto. At this point, the network diverges into two options, each of which starts with a variant of the waveform scale. The first option starts with a dominant pedal pattern in the middle register, ascends to a repeated high A that alternates with arpeggiation of the tonic triad, and ends with high harmonics arpeggiating V64 and a progression in double-stops rather than a trill. The second option quotes bar 80 of the first movement of Vanhal's Concerto before sequencing a two-beat waveform scale interspersed with repeated notes up by perfect fourth. This sequence leads to a dominant pedal in the upper register, a brief tonicization of IV, and a scalar ascent before this option ends with a similar double-stop progression. The shorter third option stems from the interpolation in bar 8, which leads to bar 34 before returning to the middle of the second option at bar 29. Example 2.43 presents harmonic reductions of all three options. The segno symbol moves to the second option, the coda symbol jumps to the third option, and the section symbol jumps back.

Example 2.41. Sperger, Cadenza network for I. Allegro mod. in Concerto No. 12, Mus 5176/7 solo part, p. 18.

Example 2.42. Sperger, Cadenza network for I. Allegro moderato in Concerto No. 12 or No. 15 (?).

Example 2.43. Harmonic Reduction of Cadenza Network for I. Allegro moderato in Concerto No. 12/15 (?).

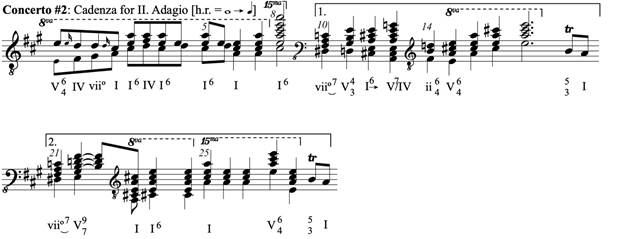

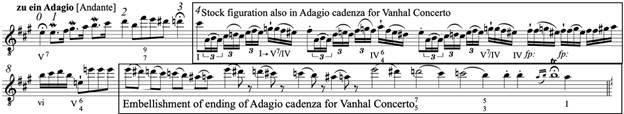

The Andante con Variazioni from Concerto No. 12 is in duple meter,45 which does not match the implied triple meter of the cadenza labeled zu ein Adagio [for an Adagio] from the cadenza sheet for Concerto No. 12 in Examples 2.44 and 2.45. Moreover, the only other second movement in theme and variations form in Sperger's contrabass concertos, the Andante poco Adagio from Concerto No. 18, lacks cadenza fermatas.46 The slow movements of Concertos No. 9 and No. 10 are in the same key as the metrically mismatched cadenza in Example 2.44, with cadenza fermatas in both solo parts over the same starting note and ending trill as this mystery Adagio cadenza; the Adagio from No. 9 is in duple meter, while the Andante from No. 10 is in triple meter.47 Due to the metric mismatch with the Adagio from Concerto No. 9, this cadenza could fit in the Andante from Concerto No. 10, allowing for the difference in the tempo marking.

This cadenza opens with an ornamented scalar outline of V7, like the long Adagio cadenza from Zimmermann's Concerto No. 1 in Example 2.14 and the Adagio cadenza for Hoffmeister's Concerto No. 3 in Example 2.31. Though this cadenza lacks bar lines, the stock sixteenth-note triplet figuration in the contrasting middle section appears in Sperger's Adagio cadenza for Vanhal's concerto with bar lines in triple meter.48 The closing of this cadenza embellishes the ending of the Adagio cadenza from Vanhal's concerto by progressively augmenting the rhythm, which changes the implied meter to duple before returning to triple at the end. The reduction in Example 2.46 shows the pedal points on V/IV and V in this cadenza.

Example 2.44. Sperger, Cadenza for an Adagio [No. 9 or 10?] in Concerto No. 12, Mus 5176/7 solo part, p. 17.

Example 2.45. Transcription of Adagio cadenza [No. 9 or 10?] in Concerto No. 12, Mus 5176/7 solo pt., p. 17.

Example 2.46. Reduction of Cadenza for II. Adagio (Concerto No. 9) or II. Andante (Concerto No. 10).

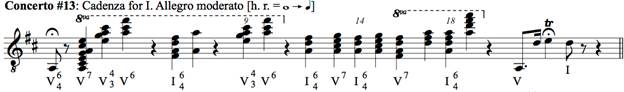

There are two sets of fermatas labeled "Cadenza" in the first movement of Concerto No. 13, one in the recapitulation and the other in the closing ritornello. Example 2.47 shows the blank line after the fermatas in the recapitulation, which leaves space for a short embellishment before the instruction Siegue [Segue], Sperger's indication for when a passage continues on the next page. Though labeled 'Cadenza,' these fermatas at an arrival on V7 invite a transitional lead-in. The piano-forte figuration following these fermatas on the next page appears in Example 2.48.

Example 2.47. Sperger, 1st 'Cadenza' fermatas for Allegro m. in Concerto No. 13, Mus 5176/6 solo part, p. 7.

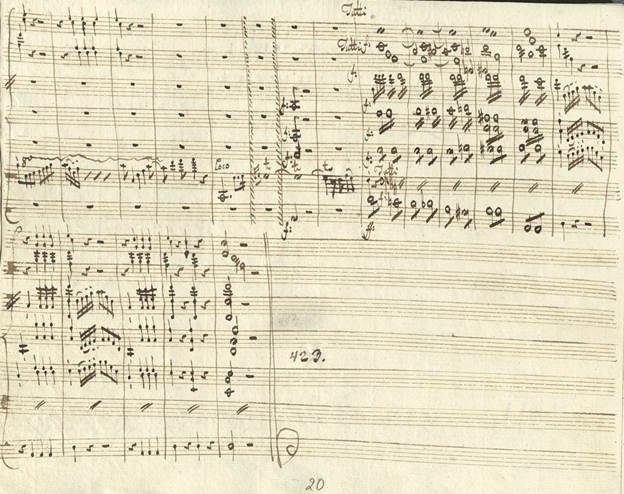

In contrast to his usual practice,49 Sperger notated the unique accompanied cadenza after the second set of fermatas in this movement directly in the solo part in Examples 2.49 and 2.50 and the score in Examples 2.53, 2.54, and 2.55, with slight differences between the sources.50 This fully metrical cadenza develops several motives from the movement by recombining them with variations in the cadenza, which demonstrates that Sperger sought to imitate an improvisatory chain of ideas even in a composed cadenza.51 Composing witty exchanges between the soloist and the winds in this cadenza freed Sperger to improvise a lead-in for the first set of fermatas.

Unlike the formulaic cadenzas for Concerto No. 12 that could fit into other concertos, the cadenza in the first movement of Concerto No. 13 derives its motives and the teasing character of its gestures from the parent movement. In the opening and the continuation, the soloist arpeggiates V7 and the cadential six-four chord in a call-and-response passage with the oboes and horns. The contrasting middle remixes the boxed triplet motive from Example 2.47 now alternating between dominant and tonic harmonies under a sustained progression in the winds. The closing section concludes with ascending arpeggiation of the cadential six-four chord that matches the boxed syncopated rhythm of a descending V7 arpeggio in the consequent phrase following the lead-in fermatas in Example 2.48. In the cadenza in the solo part, the closing trill is in the upper register, an octave higher than in the score. In the middle of this trill, the tutti string section loudly interjects on the dominant in an exaggerated parody of the tutti basso entrances notated under the cadenza fermatas in all three movements of Sperger's Concerto No. 1 (1777).52

Example 2.48. Sperger, After 1st Cadenza in I. Allegro moderato, Concerto No. 13, Mus 5176/6 solo part, p. 8.

The relative simplicity of the reduction of the solo part in Example 2.52 shows that though it only alternates between dominant and tonic in various inversions, this cadenza creates interest by juxtaposing extreme registers to create dramatic contrast, using dialogue with the orchestra to prolong harmonic tension, and gradually shortening the rhythmic subdivisions in the solo part.

Example 2.49. Sperger, cadenza for I. Allegro moderato in Concerto No. 13, Mus 5176/6 solo part, p. 8.

Example 2.50. Sperger, cadenza for I. Allegro moderato in Concerto No. 13, Mus 5176/6 solo part, p. 9.

Example 2.51. Transcription of cadenza for I. Allegro moderato in Concerto No. 13, Mus 5176/6 solo, p. 8-9.

Example 2.52. Harmonic reduction of solo part in the cadenza for I. Allegro moderato from Concerto No. 13.

Example 2.53. Accompanied cadenza in I. Allegro moderato in Concerto No. 13, Mus 5176/6 score, p. 19.

Example 2.54. Accompanied cadenza in I. Allegro moderato in Concerto No. 13, Mus 5176/6 score, p. 20.

Example 2.55. Orchestral reduction of accompanied cadenza in I. Allegro moderato in Concerto No. 13.

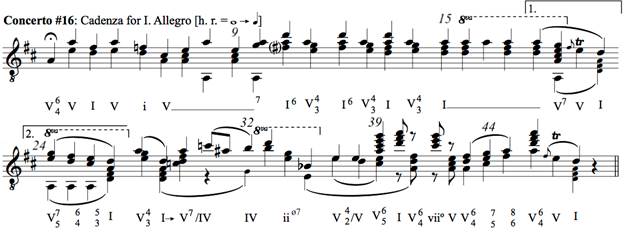

In Concerto No. 16, the first-movement cadenza fermatas occur in the closing ritornello after a seven-bar tutti. Sperger notated a cadenza for the first movement and a lead-in for the second movement on both sides of a small piece of paper in Mus 5872/4, catalogued in the Fragments and Sketches section of Meier's catalogue.53 Examples 2.56 and 2.57 present the front and back sides of this page with the lead-in inserted at the start of the third line of the front side. Sperger again uses symbols to create a cadenza with two endings, as well as the word aus [over] at the end of the first page to signal the page turn. While the first ending produces a cadenza of average length, the second ending doubles the length, resulting in Sperger's longest Allegro cadenza.

The form of this double cadenza contains a false first ending, which creates a deceptive first closing section. After the transitional second opening, the second half of this cadenza duplicates the remaining three formal functions of Sperger's cadenzas. The second continuation backtracks from the arrival on the cadential six-four chord in the first closing section, leading to a second contrasting middle section with a tempo change to Andante. While an A Tempo follows the poco Andante in the opening, no such indication appears after this Andante. Given the three-bar duration of the poco Andante, the Andante likely lasts only until the middle of the second line.

Example 2.58 shows these formal sections in bold, with boxes that indicate motives from prior cadenzas for other concertos by Sperger. The opening gambit quotes a piano bell-tone motive from the recapitulation of the first movement of Concerto No. 16, followed by a feint into the parallel minor originally from a lead-in for Concerto No. 11.54 The first continuation develops the opening motive of the first-movement cadenza for Concerto No. 10, while the first contrasting middle varies the pedal pattern from the short cadenza for Concerto No. 12. The V7/IV arpeggio and chromatic neighbor tones in the second continuation come from the second cadenza for No. 12, while the glissando figure in the second contrasting middle is from the cadenza network for No. 12. As in the cadenza for No. 13, the subdivisions progress from eighths to triplets to sixteenths.

The second half of this cadenza showcases Sperger's novel combinations of stock devices in his late cadenza style. The registral jumps in bars 41-42 create a call and response effect, while the closing scalar ascent employs double-stop thirds to imply the imitative entry of a second voice. Example 2.59 gives the harmonic reduction of this double cadenza for Concerto No. 16. While the first half alternates solely between tonic and dominant harmonies, the second half employs modal mixture in the glissando passage to imply iiø7 and then tonicizes IV and V. These secondary dominants embellish the progression IV-iiø7-V-(I), creating a greater sense of closure.

Example 2.56. Sperger, Allegro cadenza and Adagio lead-in for Concerto No. 16, Mus 5872/4, L 2n, front.

Example 2.57. Sperger, Allegro cadenza for Concerto No. 16 continued, Mus 5872/4, L 2n, back.

Example 2.58. Transcription of cadenza for I. Allegro moderato from Concerto No. 16, Mus 5872/4, L 2n.

Example 2.59. Harmonic reduction of cadenza for I. Allegro moderato from Concerto No. 16.

Though these manuscript cadenzas provide evidence of Sperger's aesthetic decisions, his creative process remains ambiguous. Do the sources examined in Part 2 represent compositional artifacts, improvisational evidence, or a combination thereof? Sperger's cadenzas show varied amounts of revision, with examples that contain crossed-out sections, scribbled-out endings, or inserted modifications. Sperger notates some cadenzas without interruption, while others contain erasures, insertions, or divergent options that create multiple beginnings or endings. Certain cadenza pages for a single concerto contain several cadenzas, which may indicate that Sperger either generated too many ideas to fit into a single cadenza or intentionally created several possible cadenzas in a brainstorming process. Comparing Sperger's handwriting in his neat autograph manuscript scores and his relatively untidy cadenzas reveals that he notated the latter in a more hurried manner, presumably for his own use in performance or as a memory aide while practicing. This trace evidence of Sperger's creative process suggests an improvisatory genesis for these cadenzas, which preserves music that was not included in the score or solo part.

This leaves the unanswerable question of when Sperger notated his cadenzas. Did he improvise the musical ideas they contain on the Viennese violone before writing them down? Or did he improvise cadenzas in his imagination, away from the instrument, and then notate them? Or could the evidence of Sperger's sometimes laborious revisions, additions, and/or insertions suggest a hybrid process of improvising ideas on the instrument, notating them, and later replacing, developing, or embellishing them? The absence of notated embellishments for almost half of the cadenza fermatas in Sperger's concertos gives rise to the possibility that Sperger did not need to notate cadenzas for every movement. The forty-four organ preludes, seven organ chorales, and two fortepiano sonatas in his estate attest to his proficiency as a keyboard player.55 Thanks to his training as an organist, Sperger could extemporize chord progressions.56 Sperger's notated cadenzas show that he realized these progressions using stock figurations that were idiomatic to the Viennese violone. By combining his ability to extemporize harmonic trajectories with a set of internalized schematic formulas, Sperger had full command of his instrument's harmonic language, which likely gave him the fluency to improvise cadenzas in performance.

The specific steps in preparing to improvise a cadenza mirror Sperger's compositional process and operate in parallel with learning a concerto. First, define the particular form of each concerto movement and identify the location and role of the main themes within that form. Next, select a variety of figurations for potential inclusion in the cadenza, using either stock formulas that appear frequently in Sperger's cadenzas or quotations from the solo or tutti episodes of the parent movement. Lastly, assemble generic schemas or concerto-specific progressions and construct a set of interlocking harmonic trajectories to use in the cadenza. Within this tonal framework, build a variable network of figurations and quoted themes so as to accumulate a wide range of possibilities to deploy when improvising. In a performance, this internalized musical constellation functions as a creative blueprint that enables the soloist to improvise new cadenzas.

Sperger used a variety of symbols, including segno and coda signs, to notate interchangeable options within his cadenzas, including corrections, insertions, and multiple beginnings or endings. This use of symbolic notation represents a valuable tool for learning the multidimensional thinking needed to improvise cadenzas, and it foreshadows Robert Levin's numbered combinatorial cadenzas for Mozart's violin and horn concertos.57 In the appendices to this article, I incorporate Sperger's symbolic notation and Levin's modular method into my approach to creating cadenza networks that facilitate the process of learning to improvise cadenzas. Rather than conceptualizing a cadenza as a pre-composed cadential extension in the closing ritornello, soloists can extemporize various cadenzas, each a different realization of a cadenza network. Heuristically, this allows for many routes between two points instead of just one straight line. The cadenza network is a preparatory step for developing the virtuosity needed to improvise cadenzas spontaneously in a concerto performance.

Improvising cadenzas using stock formulas combines skills like memory, self-assessment, and flow with prior preparation of musical materials and improvisational ideas.58 In her study of the integration of improvisation into performances by professional classical musicians, Juniper Hill describes the preparatory process of Finnish clarinetist Kari Kriikku in advance of improvising cadenzas. Kriikku cuts up copies of the score to make a cadenza by ear from a vocabulary of puzzle pieces. He found this prior preparation necessary for his cadenzas in early performances of newly learned or newly commissioned works. As a result, he is well-equipped to innovate when improvising cadenzas in later performances. Hill compares the process behind this continuous search for novelty to oral composition in storytelling, in which stock formulas complete a skeletal thematic structure,59 as with Jeff Pressing's knowledge base and referent.60

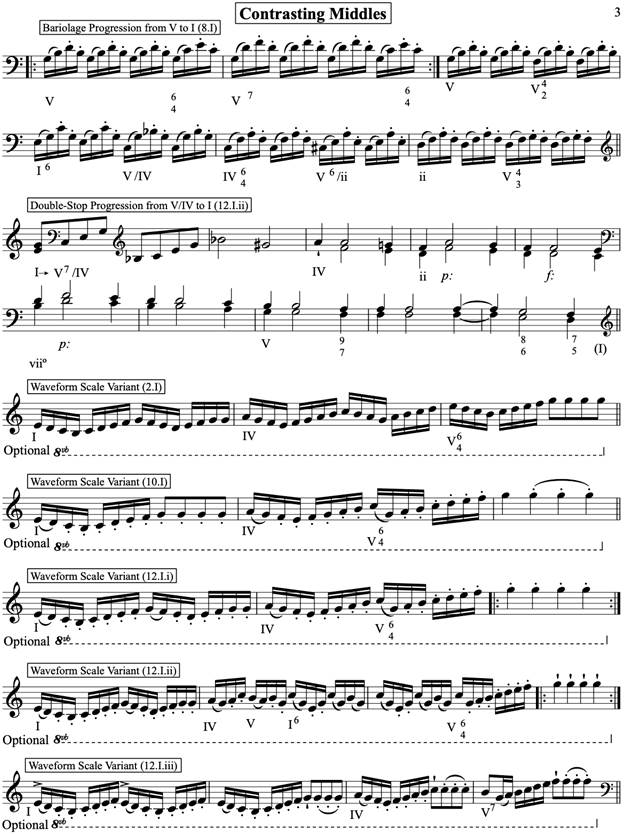

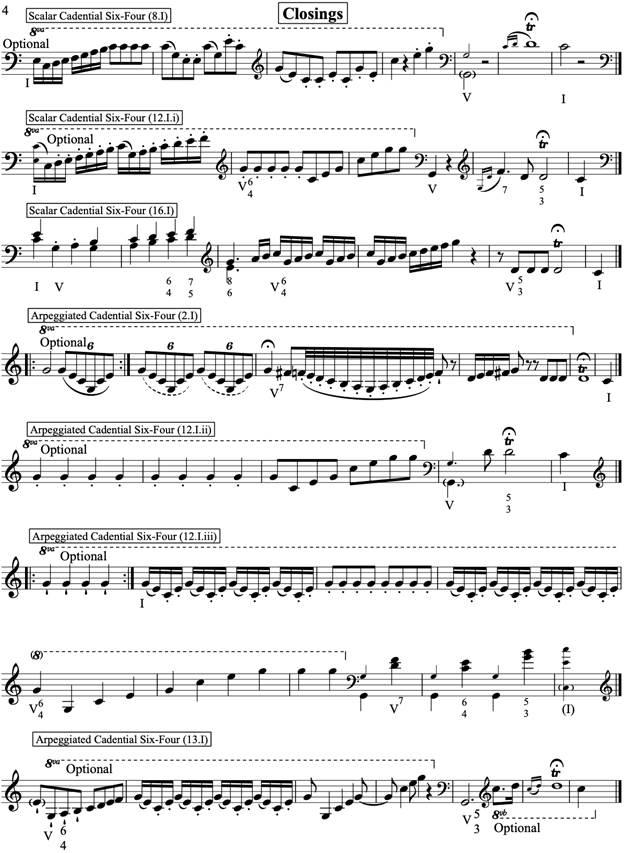

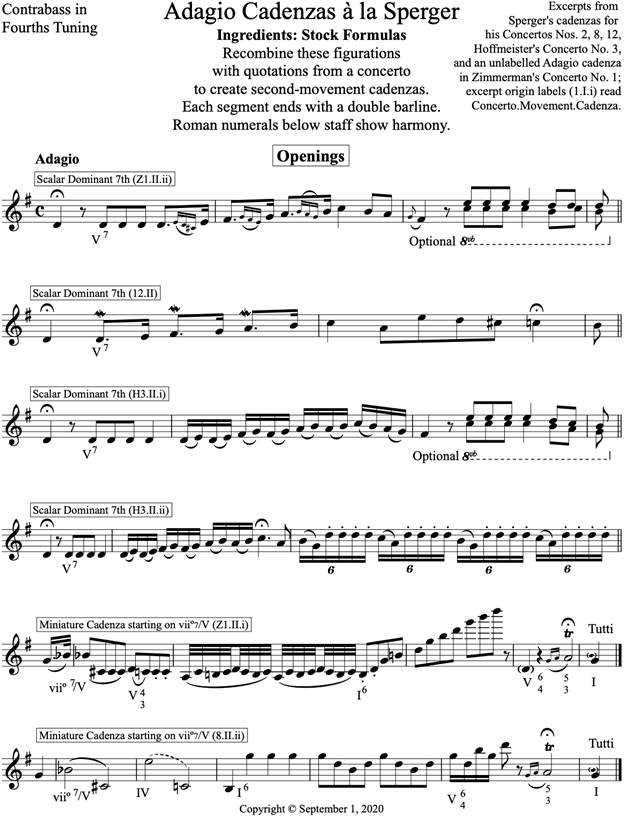

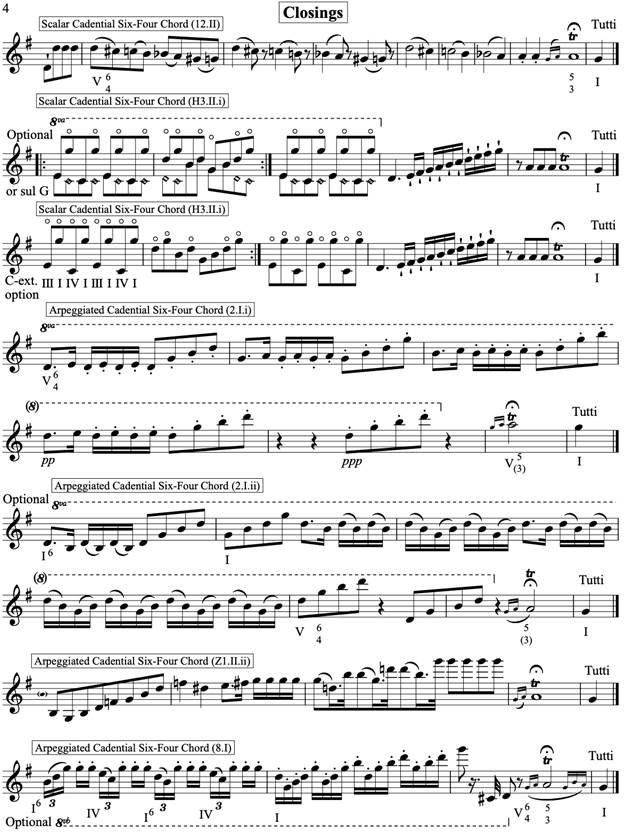

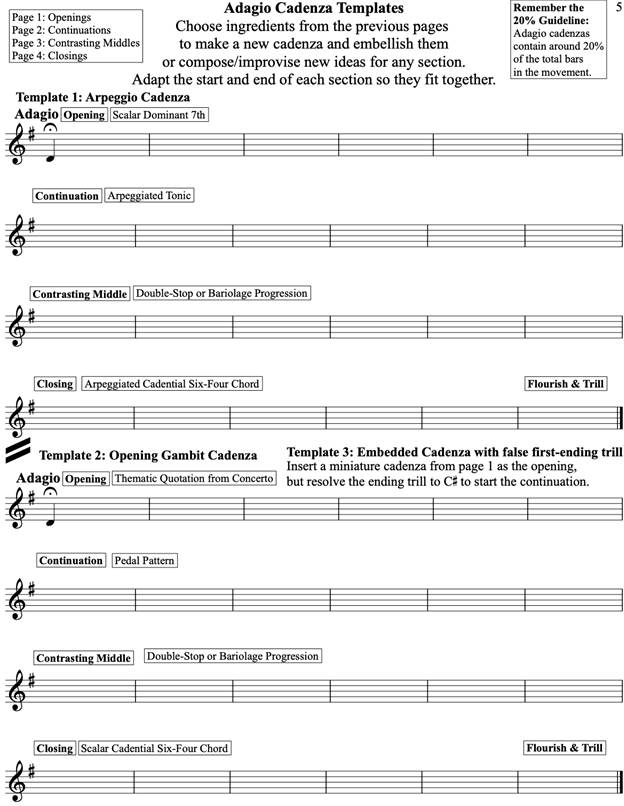

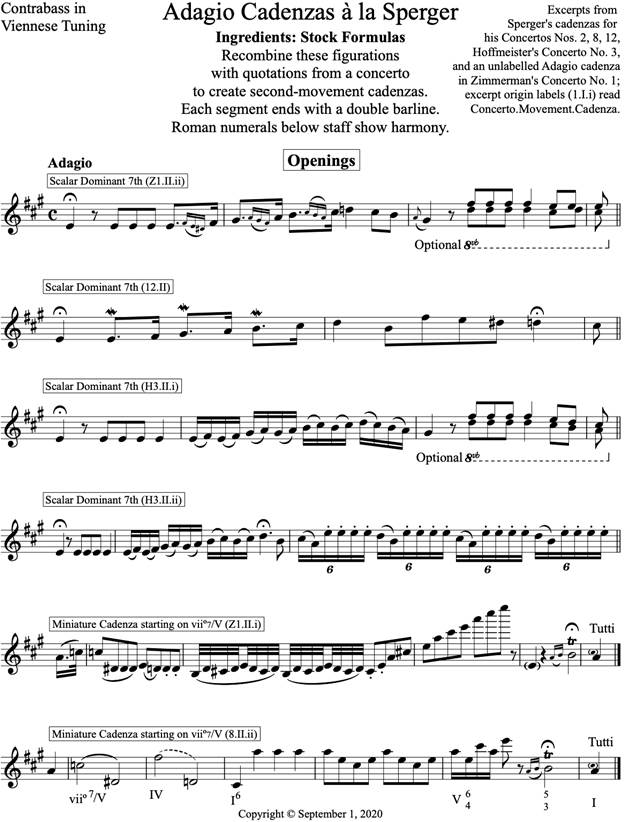

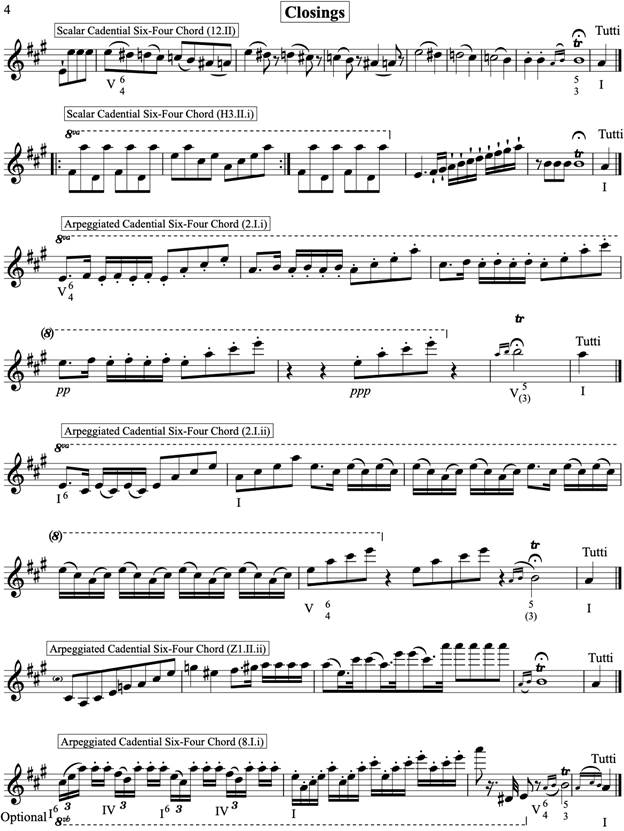

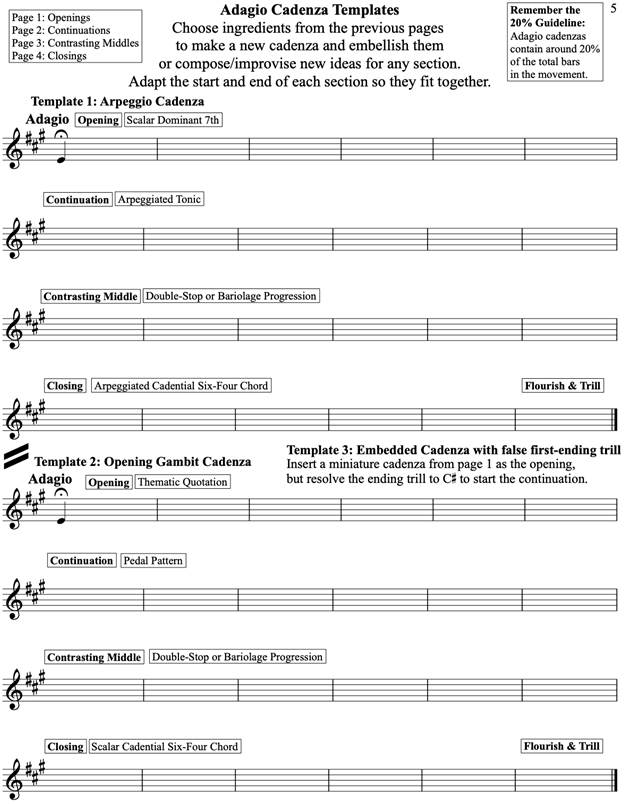

This approach to learning to improvise cadenzas, along with the succinct distillation of Mozartian cadenza figurations by Wolfgang Fetsch,61 provided inspiration for the worksheets entitled Allegro Cadenzas à la Sperger and Adagio Cadenzas à la Sperger in Appendices A, B, C, and D. The first four pages of each worksheet compile assorted figurations from Sperger's Allegro cadenzas and Adagio cadenzas, respectively, thereby assembling options for creating new cadenzas using the cadenza templates on the last page. The worksheets display the excerpts in the order in which they usually appear within Sperger's four-part cadenza form. In the Allegro cadenza worksheet, the first page contains V7 arpeggios, the second divides dominant pedal patterns by register, the third catalogues waveform scale variants, and the fourth inventories figurations of the cadential six-four chord and ending flourishes. In the Adagio cadenza worksheet, the first page furnishes openings, the second shows continuations, the third provides contrasting middles, and the fourth lists closing formulas.

The challenge with this fragmentary approach is that in order to create a coherent cadenza, each musical puzzle piece needs to align with the next in terms of register and harmony. Therefore, the arrangement of building blocks within a cadenza template depends upon fitting together the starting and ending notes of each excerpt, which the improviser can modify to create smoother transitions. Though I designed these worksheets to facilitate cadenza improvisation, they can also serve as reference tools to compare the various stock formulas and different structural templates that appear across Sperger's cadenzas.

A key metric for modern performers who endeavor to create new cadenzas for Sperger's concertos is the average length of Sperger's cadenzas in relation to their parent movement. In my doctoral thesis, I calculated the length of each of Sperger's cadenzas as a percentage of the total number of bars in the corresponding movement, excluding the cadenza itself.62 The meter preceding the cadenza fermatas determines the number of bars in unmeasured cadenzas. These calculations revealed that, proportionally speaking, Sperger wrote shorter cadenzas for his own concertos and longer cadenzas for concertos by his contemporaries. While surveys state that Mozart's piano concerto cadenzas are generally 10% of the length of the parent movement,63 Sperger's cadenzas exhibit less uniformity both over his career and among concerto movements. In Sperger's concertos with extant cadenzas, cadenzas average 7% of first movements and 18% of second movements. For concertos by Sperger's contemporaries with extant cadenzas by Sperger, cadenzas average 12.5%, 21%, and 18.5% of the three movements, respectively. The average cadenza length as a percentage of the parent movement for all the concertos in this study is 8.5% for first movements and 18% for second movements. These percentages provide a range of proportionate lengths that can guide modern performers as they create new cadenzas for concertos from the late eighteenth century. As approximate guidelines, Allegro cadenzas average ~10% and Adagio cadenzas average ~20% of the length of the parent movement.

By exploring the extant manuscript cadenzas for selected concertos in the estate of Johannes Sperger, this article uncovers new knowledge of performance practices that are applicable to historically informed pedagogy, which in turn leads toward more historically informed performances. With the goal of reviving the lost art of extemporaneous fermata embellishment, this article takes Sperger's multifaceted approach to creating cadenzas as a model to guide modern musicians who seek to learn to improvise their own. The cadenzas for fourths tuning composed in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries for cadenza collections64 and many modern editions65 of contrabass concertos from the late eighteenth century differ in style from Sperger's cadenzas to varying degrees, often by incorporating anachronistic elements. Through a stylistic study of Sperger's extant cadenzas, this article presents a selection of stock formulas and harmonic progressions from Sperger's cadenzas for his contrabass concertos and two by his contemporaries so as to equip today's performer-composer-improvisers to discover the many rewarding possibilities for creating new cadenzas. The Appendices contain worksheets called Cadenzas à la Sperger that are designed to facilitate cadenza creation by using excerpts from Sperger's Allegro cadenzas and Adagio cadenzas to fill structural templates derived from the recurring four-part form of his cadenzas. These worksheets introduce bassists to Sperger's approach to cadenza creation as they explore his concertos in either Viennese or fourths tunings.

Despite the clear differences between Viennese tuning and fourths tuning, there are commonalities that can help modern bassists to translate Sperger's idiom into fourths. There are ways to play double-stop scales in thirds in both tunings, but fourths tuning favors circle-of-fifths progressions with open strings or harmonics as bass notes, while Viennese tuning facilitates triads across strings. Fortunately for those creating cadenzas in fourths tuning, Sperger's cadenzas often prolong dominant harmonies using tension-building pedal points built around the fundamental and harmonics of the top A string, which is the same in Viennese tuning and solo tuning. Unfortunately, Sperger's cadenzas frequently arpeggiate the cadential six-four chord, which is possible entirely with natural harmonics in Viennese tuning in both D major and A major, but only in A major in solo tuning. A bass in solo tuning with a D-extension provides additional harmonics that offer partial solutions to this conundrum. Bassists without this work-around need to explore other ways to articulate the cadential six-four chord in preparation for crafting cadenzas in fourths tuning. Exercises that explore this translation process include transposing a passage down or up an octave or reducing a passage to its skeletal structure and re-embellishing it for fourths tuning with any necessary simplifications.66

Equally important to bass soloists is Sperger's role as leader of the ensemble during his concerto performances,67 which reverses the usual role of continuo players as followers laying a harmonic foundation for higher melodic instruments. In the eighteenth century, violinists likewise performed concertos as centrally located concertmasters, with the soloist playing the ripieno part during tutti ritornellos.68 By giving responsibility for directing the ensemble to the soloist, this performance practice removes the need for a separate conductor in historically imitative performances of Sperger's contrabass concertos. Sperger's extant lead-ins reveal that the soloist is responsible for fashioning the musical content within each fermata embellishment so as to give an effective cue for the tutti to enter in tempo. In contrast, some of Sperger's cadenzas contain false endings in which the soloist walks a fine line between teasing and confusing the tutti musicians as to when they will reenter. The dovetailing of Sperger's lead-ins with the music that follows them sets a high standard for modern soloists, while his intentional use of traditional gestures to maintain suspense within his cadenzas invites the soloist to engage in ludic interludes, provided that the ensemble knows the stylistic reentry signals.

Whereas the composed form of a concerto movement is prose with the possibility of embellishments in repeated material, the improvised cadenza is poetry left open for the soloist to craft.69 The cadenza is an embedded formal process, a small flexible form interpolated into a larger fixed form.70 As indeterminate elements within a concerto, cadenzas invite soloists to dramatically employ compositional devices in performance so as to complete the narrative arc of the movement in question, foreshadow the coming movements, and add a dose of musical humor or melodrama where appropriate. For attentive audiences, effective new cadenzas deepen the experience of the musical work, which exists in a plurality of realizations.71 For perceptive performers, the study of a concerto with its corresponding cadenzas illuminates both the macro-level compositional principles that guide the formal construction of each movement and the micro-level improvisational formulas and thematic transformations that create each cadenza through a retrospectively reflective formal process. The journey toward fluency in the ultimately subconscious process of improvising cadenzas requires the performer to internalize the concerto so profoundly that the performer "becomes" the composer. As a heuristic synthesis of the performer's reflections on the concerto, a cadenza is one of many solutions to a musical puzzle.

Appendix E. A map showing cities where Sperger lived in boxes and cities where he toured in ovals. 72

| Date: Dedicatee | Place | Composer | Concerto Number and Key | Manuscript Source |

| 1767: Pischelberger | Großwardein | Dittersdorf | Concerto No. 1 in E♭ major | D-SWI: Mus 1687 |

| 1767: Pischelberger | Großwardein | Dittersdorf | Concerto No. 2 in E♭ major | D-SWI: Mus 1688 |

| 1768: Pischelberger | Großwardein | Pichl | Concerto No. 1 in D major | D-SWI: Mus 4247 |

| 1768: Pischelberger | Großwardein | Pichl | Concerto No. 2 in D major | D-SWI: Mus 4246 |

| 1777 (19 Sept.) | Preßburg | Sperger | Concerto No. 1 in E♭ major | D-SWI: Mus 5176/3 |

| 1778 (17-30 Apr.) | Preßburg | Sperger | Concerto No. 2 in E♭ major | D-SWI: Mus 5176/12 score, Mus 5177/6 parts |

| 1778 (8 Aug.-8 Sep.) | Preßburg | Sperger | Concerto No. 3 in B♭ major | D-SWI: Mus 5176/1 |

| c1778: Sperger | Preßburg | Zimmermann | Concerto No. 1 in D major | D-SWI: Mus 5817 |

| c1778: Kämpfer | Preßburg | Zimmermann | Concerto No. 2 in D major | A-KR: H 48/147 |

| 1779 | Preßburg | Sperger | Concerto No. 4 in F major | D-SWI: Mus 5176/2 |

| 1779 | Preßburg | Sperger | Concerto No. 5 in E♭ | D-SWI: Mus 5174/2a |

| 1779 (12 July) | Preßburg | Sperger | Concerto No. 6 in G major | D-SWI: Mus 5176/9 |

| 1781 (1 September) | Preßburg | Sperger | Concerto No. 7 in A major | D-SWI: Mus 5176/8 |

| 1783 (28 July) | Kofidisch | Sperger | Concerto No. 8 in E♭ major | D-SWI: Mus 5177/4 |

| c1785: Pischelberger | Vienna | Hoffmeister | Concerto 'No. 1' in E♭ major (Adagio with obbligato violin) | A-WGM: IX 6394 |

| 1785-86 1786-87 |

Kofidisch Vienna |

Sperger | Concerto No. 9 in E♭ major | D-SWI: Mus 5177/7 |

| 1787 | Berlin | Sperger | Concerto No. 10 in E♭ major | D-SWI: Mus 5177/1 |

| 1787 | Vienna | Sperger | Concerto No. 11 in B♭ major | D-SWI: Mus 5177/2 |

| c1787 | Vienna | Sperger | Adagio in D major for Cb./Orch. | D-SWI: Mus 5180 |

| c1786-89: Sperger | Vienna | Vanhal | Concerto in E♭ major | D-SWI: Mus 5512 |

| c1786-89: Sperger | Vienna | Hoffmeister | Concerto 'No. 3' in E♭ major | D-SWI: Mus 2850 |

| After c1789: Pischelberger | Vienna | Hoffmeister | Concerto 'No. 2' in D major | A-WGM: IX 6393 |

| c1789-1793 | Ludwigslust | Sperger | Romance in D min. for Cb./Str. | D-SWI: Mus 5178 |

| c1790-1792 | Ludwigslust | Sperger | Concerto No. 12 in E♭ major | D-SWI: Mus 5176/7 |

| c1792 | Ludwigslust | Sperger | Concerto No. 13 in D major | D-SWI: Mus 5176/6 |

| c1793-94 | Ludwigslust | Sperger | Concerto No. 14 in E♭ major | D-SWI: Mus 5174/2b |

| 1796 | Ludwigslust | Sperger | Concerto No. 15 in D major | D-SWI: Mus 5177/5 |

| c1796-1797 | Ludwigslust | Hoffmeister, rev. Sperger |

Adagio for Cb./Str. in B♭ major (revision of Adagio in Mus 2850) |

D-SWI: Mus 5179 |

| 1797 (August) | Ludwigslust | Sperger | Concerto No. 16 in E♭ major | D-SWI: Mus 5176/11 |

| 1805 (8 November) | Ludwigslust | Sperger | Concerto No. 17 in B♭ major | D-SWI: Mus 5176/4 |

| 1807 (20 August) | Ludwigslust | Sperger | Concerto No. 18 in C minor | D-SWI: Mus 5176/5 |

Library Sigla Abbreviations:

A-KR: Benediktinerstift Musikarchiv in Kremsmünster, Austria

A-WGM: Archiv der Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde in Vienna, Austria

D-SWI: Landesbibliothek Mecklenberg-Vorpommern in Schwerin, Germany

1 David Dolan, "Back to the Future: Towards the Revival of Extemporization in Classical Music Performance," in The Reflective Conservatoire: Studies in Music Education, ed. George Odam and Nicholas Bannan (Aldershot: Ashgate, 2005), 91-126. David Dolan, "Walking Freely on a Firm Ground," Music in Time (January 2000): 13-20.

2 Robin Stowell, "Performance Practice in the Eighteenth-Century Concerto," in The Cambridge Companion to the Concerto, ed. Simon P. Keefe (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005), 218, 220-221.

3 William Drabkin, "An Interpretation of Musical Dreams: Towards a Theory of the Mozart Piano Concerto Cadenza," in Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart: Essays on His Life and His Music, ed. Stanley Sadie (New York: Oxford University Press, 1996), 163. The analogy between cadenzas and dreams originally appears in Daniel Gottlob Türk, School of Clavier Playing [1789], trans. Raymond H. Haggh (Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1982), 498n18.

4 Christoph Wolff, "Cadenzas and Styles of Improvisation in Mozart's Piano Concertos," in Perspectives on Mozart Performance, ed. R. Larry Todd and Peter Williams (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991), 229-232. See also Türk, School of Clavier Playing, 289-296.

5 Robert Levin, "Instrumental Ornamentation, Improvisation and Cadenzas," in The Norton/Grove Handbooks in Music: Performance Practice, Music After 1600, ed. Howard Mayer and Stanley Sadie (London: W. W. Norton & Co., 1989), 284.

6 Eva and Paul Badura-Skoda, Interpreting Mozart: The Performance of His Piano Pieces and Other Compositions, 2nd ed. (New York: Routledge, 2010), 213-250.

7 Robin Moore, "The Decline of Improvisation in Western Art Music: An Interpretation of Change," International Review of the Aesthetics and Sociology of Music 23, no. 1 (June 1992): 67-72. For a discussion of Sperger's place in this shift from aristocratic to bourgeois music-making, see Josef Focht, "Music in Ludwigslust: The Double Bassists Around Sperger and Their Places of Action," Magazine of the International J.M. Sperger Society (2019): 14-18.

8 See Appendix E for a map showing the cities where Sperger lived, worked, and performed. See Appendix F for a partial chronological list of contrabass concertos by Sperger and his contemporaries. For biographical background on Sperger in English, see Josef Focht, "Die Position Spergers als Kontrabassist der Mecklenburg-Schweriner Hofkapelle" [Sperger's Position as Double Bassist of the Mecklenburg-Schwerin Court Orchestra], trans. James Lambert, Sperger Forum 2/3, 4/5 (2004, 2006): 35; Klaus Trumpf, "Johann Sperger," trans. Sharon Brown, Bass World 1, no.3 (1975): 86-90; Klaus Trumpf, "Mozart Requiem for a Double Bassist," trans. Anja Weineck-Hucke with Vincent Osborn, Bass World 40, no. 1 (2017): 59-62; Klaus Trumpf, "The Mozart Requiem for a Double Bassist (Part 2): Viennese-Tuned Double Bass," Bass World 40, no. 3 (2018): 25-31; and Klaus Trumpf, "The Mozart Requiem for a Double Bassist, Part 3," trans. Vincent Osborn, Bass World 41, no. 3 (2019): 17-21.

9 For modern examples of cadenza networks, see Robert Levin, Cadenzas to Mozart's Violin Concertos, preface by Gidon Kremer (Vienna: Universal Edition, 1992).

10 Carl Philip Emanuel Bach, Essay on the True Art of Playing Keyboard Instruments [Berlin, 1753/1762], trans. and ed. William J. Mitchell (New York: W. W. Norton & Co., 1949), 142-146. Johann Joachim Quantz, On Playing the Flute [Berlin, 1752], trans. Edward R. Reilly (New York: Schirmer Books, 1985), 179-187. Türk, School of Clavier Playing [Leipzig, 1789], 297-309. Eva and Paul Badura-Skoda, Interpreting Mozart, 213-288. Levin, "Instrumental Ornamentation, Improvisation and Cadenzas," 267-291. Frederick Neumann, Ornamentation and Improvisation in Mozart (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1986), 240-281. Philip Whitmore, Unpremeditated Art: The Cadenza in the Classical Keyboard Concerto (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1991). Eva Badura-Skoda, "On Improvised Embellishments and Cadenzas in Mozart's Piano Concertos," in Mozart's Piano Concertos: Text, Context, Interpretation, ed. Neal Zaslaw (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1996), 365-371. Wolfgang Fetsch, "Cadenzas in the Mozart Concertos," Clavier 30, no. 10, (Dec. 1991), 13-17. Christoph Wolff, "Cadenzas and Styles of Improvisation in Mozart's Piano Concertos," 228-38. Chrisoph Wolff, "Zur Chronologie der Klavierkonzert-Kadenzen Mozarts," Mozart-Jahrbuch 1978-79, 235-246. Neal Zaslaw, "One More Time: Mozart and His Cadenzas," in The Century of Bach and Mozart: Perspectives on Historiography, Composition, Theory, and Performance (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2008), 239-249. Eduard Melkus, Cadenzas for Mozart's Violin Concertos (Vienna: Doblinger, 2013). Eduard Melkus, "On the Problem of Cadenzas in Mozart's Violin Concertos," in Perspectives on Mozart Performance, ed. R. Larry Todd and Peter Williams, trans. Tim Burris (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991), 74-91. Robin Stowell, "Improvisation," in Violin Technique and Performance Practice in the Late Eighteenth and Early Nineteenth Centuries (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985), 337-367. Zachary Ebin, "Period Style Cadenzas for Mozart's Violin Concertos," American String Teacher (February 2012): 38-43. Natalie Farrell, "Facing the Fermata: Recreating the Classical Cadenza in Modern Performances of Mozart's Flute Concerti," The Flutist Quarterly (Fall 2016): 35-38. Leslie Hart, "The Creative Hornist: Improvising Cadenzas in Mozart," The Horn Call - Journal of the International Horn Society 40, no. 3 (May 2010): 67-69. Betty Bang Mather and David Lasocki, The Classical Woodwind Cadenza: A Workbook (New York: McGinnis & Marx, 1979).

11 Adolf Meier, "The Vienna Double Bass and Its Technique During the Era of the Vienna Classic," trans. Klaus Schruff, International Society of Bassists Journal 13, no. 3 (Spring 1987): 10-16.

12 Josef Focht, "Solo Music for the Viennese Double Bass and Mozart's Compositions with Obbligato Passages for Double Bass." International Society of Bassists Journal 18, no. 2 (Fall 1992): 45-52.

13 Josef Focht, Der Wiener Kontrabass: Spieltechnik und Auffürungspraxis, Musik und Instrumente [The Viennese Contrabass: Playing Technique and Performance Practice, Music and Instruments] (Tutzing: Hans Schneider, 1999). Adolf Meier, Konzertante Musik für Kontrabass in der Wiener Klassik [Concertante Music for Contrabass in Viennese Classicism](Giebing über Prien und Chiemsee: Musikverlag Emil Katzbichler, 1969). Alfred Planyavsky, Geschichte des Kontrabasses [History of Double Basses](Tutzing: Hans Schneider, 1984). Igor Pecevski, "The Double Bass Playing Technique of J. M. Sperger," in Geschichte, Bauweise und Spieltechnik der tiefen Streichinstrumente, ed. Monica Lustig (Blankenburg: Stiftung Kloster Michaelstein, 2000): 129-138.

14 J. M. Sperger, Konzert D-Dur (Nr. 15) für Kontrabass und Orchester, ed. Michinori Bunya, cad. Claus Kühnl (Hofheim: Friedrich Hofmeister Musikverlag, 1999), ii. " . . . bemerkenswert ist auch das nur einmal überraschend aufretende neue Thema in der Durchfürung — ob Sperger darüber vielleicht in einer Kadenz improvisieren wollte?"