Volume 16 of the OJBR presents A Technical Guidance for the Dragonetti Concerto In A Major By Édouard Nanny and Beyond by Irmak Sabuncu.

Dr. Sabuncu's article presents technical preparation exercises and corresponding background information for students who are learning Dragonetti's famous double bass concerto. The article can also be consulted by double bass teachers who are guiding students who are in the process of learning the concerto. The article offers solutions to identified technical challenges involving bow stroke, thumb position, harmonics, and intonation/shifting. In addition to his own teaching experiences, Dr. Sabuncu's article is informed by his teachers, Duncan McTier, Bozo Paradzik, and Jeff Bradetich.

Dr. Sabuncu obtained his D.M.A. in the double bass studio of Professor Jeff Bradetich at the University of North Texas in May 2021. He was also a teaching fellow at the University of North Texas from 2017 to 2020. He completed his practical training in Bern Symphony Orchestra (Switzerland) in 2011. From 2012-2017, he worked as a double bass lecturer at the Mersin University, State Conservatory.

The Dragonetti A Major concerto1 was originally written by Édouard Nanny, one of the most prominent bassists of the French Contrabass School2. An examination of the structure of Dragonetti's concertos and É. Nanny's technical approaches in his well-known double bass methods will provide clarity to this fact. Thus, this concerto is the subject of this article and my doctoral thesis. Moreover, it is considered a milestone of double bass literature for students primarily due to its technical methods.

One of the biggest challenges for students and teachers while studying a new piece is defining the technical problems and determining an appropriate work plan. Therefore, this article is written to serve as a pedagogical pathway to preparing and performing the first and second movements of the Dragonetti Concerto in A Major for Double Bass and Orchestra, which is based on my recently published doctoral thesis, "A Technical Preparation Guide for the Dragonetti Concerto in A Major for Double Bass and Orchestra by Édouard Nanny."

The technical challenges are listed as "Bow Stroke Types and Their Practice Suggestions in the Piece," "Thumb Position," "Harmonics," and "Intonation and Shifting." Each title is exemplified with a selected passage from the concerto, followed by explanations of technical difficulties, suggestions for solutions, exercises, and etudes.

The problems and suggestions I address in this paper are based on my teaching experiences at the Mersin University State Conservatory in Turkey and the University of North Texas. It is also influenced by my observations of the pedagogical approaches of Professor Duncan McTier, Bozo Paradzik, and Jeff Bradetich with whom I have had the privilege to study.

Producing the desired sound requires the student to understand that the instrument is sensitive to touch and reacts accordingly. Therefore, being conscious of the standard elements below will be beneficial in obtaining the aimed sonority:3

Furthermore, the vibration frequency of the string determines the pitch, and the vibration amplitude determines the dynamics of the sound produced. This fact needs particular consideration for the strength and speed applied.

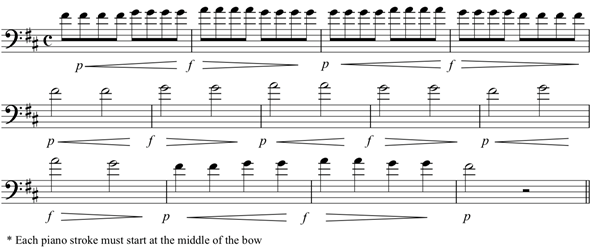

Based on these principles, the first exercise (Exercise 1), is derived from the method books of two cello masters from the 20th century: P. Tortellier's How I Play How I Teach4 and M. Eisenberg's Cello Playing of Today5. The exercise should use a full bow at the closest possible spot to the bridge, with maximum string vibration, and change the bow right on the tip and frog. The goal is to raise awareness of the abovementioned principles while suggesting them as a daily practice.

Exercise 1. Irmak Sabuncu, Exercise for Detaché

Slow quarter notes often appear simple, yet they can be problematic in terms of musical expression (Example 1). Besides the sonority requirements, the necessity of crescendo and decrescendo dynamics while applying the bow proportion is a challenge.

The section from the opening of the second movement of the Dragonetti A Major Concerto is demonstrated below:

Example 1. Dragonetti, Concerto in A Major, I, mm. 9-10

Exercise 2 (below) was tailored as a study concerning the challenges.

Exercise 2. Irmak Sabuncu, Exercise for Detaché

Two facts must be considered in this exercise. First, increase the bow proportion to attain the desired crescendo or the opposite for the decrescendo. Second, point the bow tip down on each bow stroke to ensure that it moves closer to the bridge. Crescendo and decrescendo should be considered horizontal movements rather than vertical movements so, using excessive strength should be avoided.

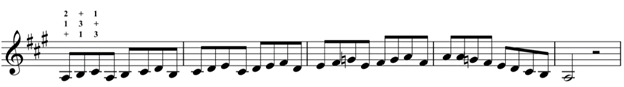

The following section contains alternating groups of the slurred and detached sixteenth and triplet notes.

Example 2. Dragonetti, Concerto in A Major, I, mm. 42–45

The principle is to focus on the minimum number of simultaneous problems and master the skill with the simplest exercise. Thus, Exercise 3 is for preliminarily focusing on the placement, strength, proportion, speed, and angle of the right hand in playing the sixteenth note. It is only performed with note A to ensure bow placement without using the left hand.

Exercise 3. Irmak Sabuncu. Exercise for Sixteenth

The challenge with playing triplets is to divide the beat into three instead of four. It requires a different bow to play each stroke (the first stroke is a downbow, and the second is an upbow or otherwise). This creates a challenge for muscle memory. Exercise 4 will also be a preliminary study for this, and the basic principles mentioned for the right hand.

Exercise 4. Irmak Sabuncu. Exercise for Triplets

The principle of playing the two-slurred, one-separate triplet figure is for playing the third note off the string at the frog. As a pre-workout, at the last measure of Exercise 4, it is recommended to play the A at the first half of the bow, close to the frog by an upbow.

As a continuation, Exercise 5 is designed to improve triplet playing along with left and right-hand coordination. It is derived from the tune called "Max's Magic" from J. Bradetich's technical exercises.6

Exercise 5. Irmak Sabuncu, Exercise for Triplets

Although it is not directly relative to the bow strokes, a principle to consider is that left wrist movements support left-hand finger movements. The left wrist should rotate in the direction of finger movement, resembling a vibrato. In this way, the exercise will also provide ease for left and right-hand coordination. As in Exercise 4, it is recommended to play close to the frog.

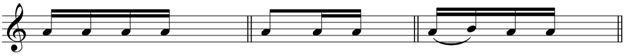

Following the coordination study, Exercise 6 can potentially contribute to a fluent G major scale when played with various fingerings.

Exercise 6. Irmak Sabuncu, Exercise for Variations

Exercise 7, inspired by Kreutzer Fiorillo7, can be applied as a final study to offer a systematic development before proceeding to the etude.

Exercise 7. Irmak Sabuncu, Exercise for Variations

The etude number two from Kurt B. Möchel's8 book Zweck-Etüden für Kontrabass will complement the Exercises 1-7.

Figure 3. Kurt B. Möchel, Zweck-Etüden für Kontrabass, 8, 9

The literature suggests that a correct thumb position is critical for pieces from the beginning to the most advanced level. This section contains brief suggestions without quotations from the concerto.

The curved shape of the fingerboard in string instruments makes the consciousness of intonation necessary while performing horizontally, that is, in the same position. It is even more distinct in the thumb position. This paper contains pictures of the thumb position and some helpful horizontal exercise suggestions for the thumb position.

The primary step for an ideal thumb position is to obtain the ideal hand position, which allows pressing the fleshy parts of the first, second, and third fingers without contraction. The lengths of fingers, the size of palm, and the position of the thumb on the string are the determining factors for the shape and position of the left hand. The examples below show the common thumb positions, and Picture 4 shows the recommended hand position.

Picture 1 |

Picture 2 |

Picture 3 |

Picture 4 |

Another suggestion to prevent the left arm from contracting is to minimize the distance of the left wrist from the left shoulder. As the left hand moves away from the shoulder, controlling becomes challenging, which causes a contraction of the whole body, starting at the left arm. Picture 6 is the recommended arm position.

Picture 5 |

Picture 6 |

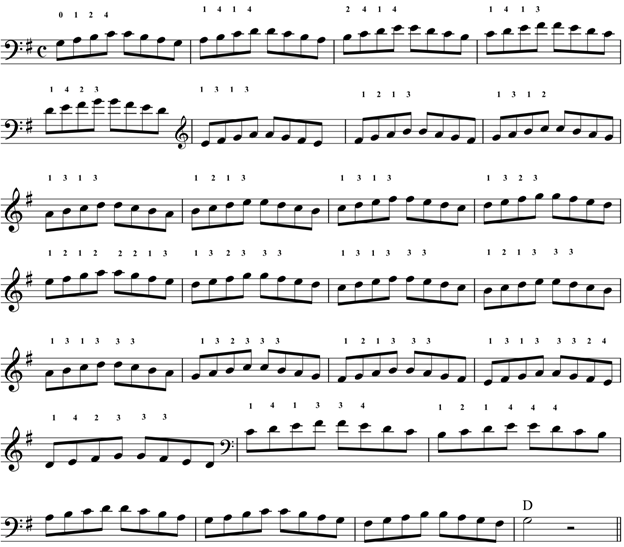

These recommendations for a healthy and effective thumb position should be considered when executing the A Mixolydian scale in Exercise 8 (below). Besides playing in the same position, the left wrist should move in the finger's moving direction while executing this example. Thus, the action is carried out with the whole hand and not only with the fingers. As a result, the hand will not be stiff, and the player gains extra speed.

Exercise 8. Irmak Sabuncu, Exercise for Thumb Position

A subsequent study (Exercise 9) contributes to the string-crossing ability of horizontal playing. This exercise was derived from Jeff Bradetich's "thumb drill" exercise.9

Exercise 9. Irmak Sabuncu, Exercise for Thumb Position

Finally, it is worth briefly mentioning the hand size adaptation. Because the positions on the fingerboard become smaller as one gets closer to the bridge, the hand position needs to be adapted to it. Exercise 10 aims to help the hand size adaption on different places of the fingerboard by executing the C and G major scales with the same fingering pattern.

Exercise 10. Irmak Sabuncu, Exercise for Thumb Position

One of the reasons for choosing the Dragonetti Concerto for this article is that it can be used to teach the fundamentals of basic double bass techniques, including playing harmonics. As a practice method, addressing the challenge as a horizontal and vertical approach is helpful for the beginner level. Vertical playing means arpeggios on the same string executed by position change, while horizontal playing is a lyrical passage in the same position in the high register managed by string crossing. A selection from the first movement of the concerto that exemplifies vertical playing is shown below in Example 4.

Example 4. Dragonetti, Concerto in A Major, I, mm. 108–115

Picture 7 depicts the recommended hand shape for the first position. Generally, the first three notes of the arpeggio are played using the thumb, first, and third fingers, respectively. The inward first finger will help the third finger to reach the third note of the arpeggio.

Picture 7

It is more effective to have an approach that considers each octave as one hand position (Pictures 8a and 8c) after the awareness of these two positions by studying the transition motion between them (Picture 8b). Pictures 8a, 8b, and 8c are the recommended left hand transition motions on the same string.

Picture 8a |

Picture 8b |

Picture 8c |

It is helpful to pay attention to the bow angle while playing vertical harmonics. If the bow's tip is facing downward, it veers toward the bridge, but it swerves toward the fingerboard if its tip is facing upward. Picture 9a is the suggested bow angle for ascending harmonic arpeggios movement and 9b is for the descending harmonic arpeggios.

Picture 9a |

Picture 9b |

Finally, the following exercises (Exercises 11, 12, 13, and 14) will contribute to the memory of the left hand, the internalization of the position transition motion, and the execution of the whole arpeggio by muscle memory.

Exercise 11. Irmak Sabuncu, Exercise for Harmonic Arpeggios

Exercise 12. Irmak Sabuncu, Exercise for Harmonic Arpeggios

Exercise 13. Irmak Sabuncu, Exercise for Harmonic Arpeggios

Exercise 14. Irmak Sabuncu, Exercise for Harmonic Arpeggios

Example 5 shows the section from the concerto's second movement as a sample of playing the song-like horizontal harmonics.

Example 5. Dragonetti, Concerto in A Major, 2, mm. 53–60

The general problems in lyric harmonic playing that evoke the whistle are as follows:

Considering these potential problems, Exercises 15 and 16 will promote awareness of the right hand and describe the left hand's position for each note.

Exercise 15. Irmak Sabuncu, Exercise for Harmonic Arpeggios

Exercise 16. Irmak Sabuncu, Exercise for Harmonic Arpeggios

Exercises 17 and 18 additionally include string crossings in harmonic playing. If the third finger is not long enough, playing the D on the G string (second finger) and C on the D string (third finger) can be tricky. In this case, tilting the left hand as far left as possible and holding it horizontal to the bridge will expand the range of the third finger.

Exercise 17. Irmak Sabuncu, Exercise for Harmonic Arpeggios

Exercise 18. Irmak Sabuncu, Exercise for Harmonic Arpeggios

The G major arpeggio at the opening of Dragonetti Concerto is often a challenge in terms of intonation and shifting (Example 6).

Example 6. Dragonetti, Concerto in A Major, 1, mm. 1-13

The problematic approach is practicing the transition between these notes before being mentally sure about these notes. It often results in frustration. I propose a two-step approach to avoid this issue. The first step is to play these notes one octave lower, which establishes the correct intonation mentally. The second step is shifting, which is the transition between two notes. Let us assume the first note (G) as the departure point and the second note (B) as the arrival point. A common mistake is trying to shift directly without being conscious of the intonation and location of the arrival point. Instead, correctly adopting the departure and arrival points by practicing them individually in terms of location and intonation can achieve a reliable shift more accurately. It is recommended to execute these three notes of G Major arpeggio only by the second finger for a powerful opening.

Some frequent challenges for beginner or intermediate-level players are the uncertainty of the correct intonation and the inability to listen properly. The following section from measures 73-78 in the first movement of the concerto is chosen to work on these issues.

Example 7. Dragonetti, Concerto in A Major, 1, mm. 73–78

A common mistake in executing the first measure is not listening properly to the first two notes, E and B (red), and instead focusing on the high B and C (blue) at the thumb position (Example 8). The important principle for string instruments is that every executed note is a reference to the next. Since the G is harmonic in this passage, it will make the intonation problem even more transparent.

Example 8. Dragonetti, Concerto in A Major, 1, mm. 73

Exercise 19 was tailored based on the challenges previously mentioned. It aims to approach each note individually by neglecting the passage's rhythmic structure. The exercise is structured to play each note accurately and serve as a reference for playing the next note correctly. Notably, executing a staccato in the slur requires applying the right hand after pressing the left-hand note. This practice makes listening to each note easier and obtaining an optimum bow proportion.

Exercise 19. Irmak Sabuncu, Exercise for Intonation and Shifting

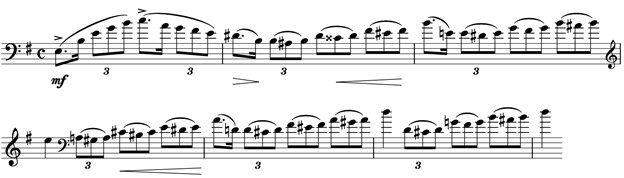

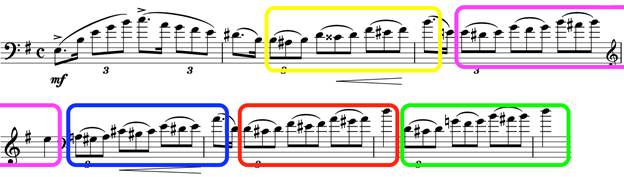

Passages like Example 9 become problematic both musically and intonation-wise if they are practiced note by note. However, it is useful to take a look at the structure of the passage before attempting to practice it. The first notes of the triplets and the first note of the next bar (in yellow) are the notes of a B major arpeggio. The next similar sequence is in the key of E minor (marked in purple), then A major (in blue color), followed by D Major (red), and the figure in the green is the G Major 6/4 chord, resolved by a final D major arpeggio.

Example 9. Dragonetti, Concerto in A Major, 1, mm. 76-78

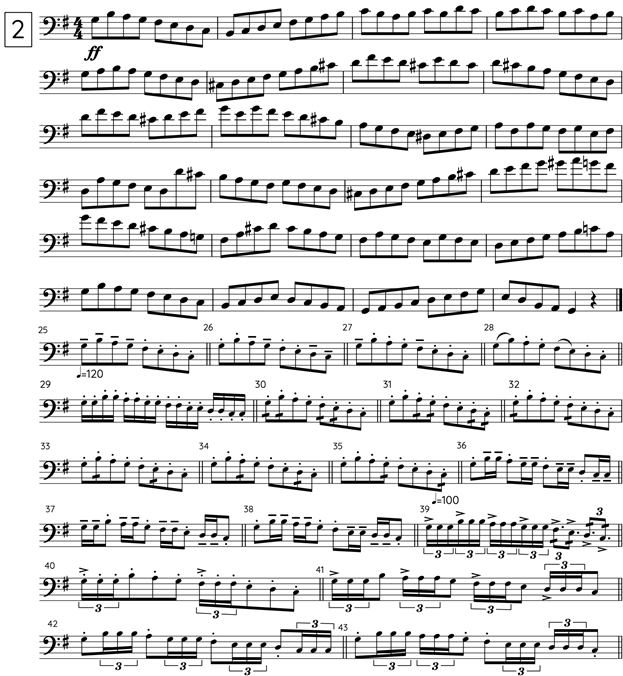

Studying this section as an arpeggio, without the inclusion of its chromatic ornaments (Exercise 20), is beneficial for a more accurate intonation, and it also contributes to a better musical understanding of the passage. The practice method for Examples 7 and 8 is also applicable here.

Exercise 20. Irmak Sabuncu, Exercise for Intonation and Shifting

The chapters "Bow Stroke Types in the Piece and Suggestions" and "Thumb Position" contain exercises tailored for left-right hand coordination, slurred and detaché sixteenth-note and triplets playing, and recommendations for playing in thumb position (Exercises 1-7 and Example 3, Picture 1-6). These serve as preparatory drills for passages like the following section from J. M. Sperger Double Bass Concerto No: 1510 first movement.

Example 10. J. M. Sperger, Concerto No: 15, mm. 76-83

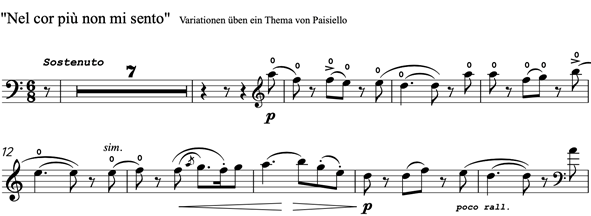

The preparatory exercises and guidance for the vertical execution of the harmonic arpeggio movements and the horizontal lyrical playing on the harmonics are presented under the chapter "Harmonics" (Exercises 11-18). Although the suggestions and exercises aimed to approach Dragonetti's A Major concerto's specific sections, it is possible to come across similar passages in many works written for double bass, especially in the works written by G. Bottesini. In this context, the recommendations presented in this section shall contribute to the player's technical skills as a preliminary preparation for the specific sections from "Nel core piu non mi sento" by G. Bottesini11 and similar challenges.

Example 11. G. Bottesini, "Nel cor più non mi sento", mm. 9-16

Example 11. G. Bottesini, "Nel cor più non mi sento", mm. 107-110

Arpeggio passages embellished by neighboring chromatic notes (mentioned under the Chapter "Intonation and Shifting") are often encountered in string literature. The suggested method of practicing only the main notes of the arpeggio without the surrounding chromatic embellishment is also applicable for the following three sections of the first movement of the Koussevitzky F# minor Concerto12.

Example 12. Koussevitzky, Concerto in F# minor, 1, mm. 61-62

Example 13. Koussevitzky, Concerto in F# minor, 1, mm. 65

Example 14. Koussevitzky, Concerto in F# minor, 1, mm. 67

As stated in the introduction, choosing an adequate approach towards the technical challenges and finding a solution for them can be an overwhelming task at the beginning stages of practicing a new piece.

In response, this article evaluated the problems that pose a technical challenge for the double bass playing through excerpts from the Dragonetti A Major Concerto and presented exercises that are designed as solutions for them.

However, these technical difficulties are not specific to this concerto and they are often encountered within the repertoire of the instrument. Therefore, these ideas aim to provide a preliminary study for the works of the literature that are both technically and musically more demanding than the Dragonetti A Major Concerto. Therefore, this article primarily stands as a practice guide to the concerto but can also serve as a collection of preliminary exercises beneficial to other works in the instrument's literature.

1 Domenico Dragonetti. Concerto pour Contrebasse à Cordes et Piano. Paris: Alphonse Leduc, 1925.

2 See, for example, Paul Brun, A New History of the Double Bass (Villeneuve d'Ascq: P. Brun Productions, 2000), 95; Philip H. Albright, "Original Solo Concertos for The Double Bass" (DMA document, University of Rochester, 1969), 29–35; and Rodney Slatford, "Domenico Dragonetti," Proceedings of The Royal Musical Association 97, no. 1 (1970): 21–28.

3 J. Bradetich, private lessons, August 2017- May 2021.

4 Paul Tortellier, How I Play, How I Teach (London: Chester Music, 1988), 38.

5 Maurice Eisenberg, Cello Playing of Today (Great Britten: Lavender Publications, 1966), 26.

6 Jeff Bradetich, The Ultimate Challenge (USA Idaho: Music for All to Hear, 2009).

7 Nanny, Edouard, Rodolphe Kreutzer, and Federigo Fiorillo. Études de Kreutzer et de Fiorillo. Paris: Alphonse Leduc, 1921.

8 Kurt B. Möchel, Zweck-Etüden für Kontrabass = Etudes Pratiques Pour la Contrebasse = Special Studies for Double Bass (Mainz: B. Schott's Söhne, 1931), 8, 9.

9 Jeff Bradetich. Double Bass: The Ultimate Challenge. [Juliaetta, ID]: Music for All to Hear, 2009.

10 Johann Matthias, Sperger. Konzert D-dur Nr. 15 für Kontrabass und Orchester. Arranged for double bass and piano by Michinori Bunya. Leipzig: Friedrich Hofmeister, 1999, 2.

11 Giovanni Bottesini, Klaus Trumpf. Ausgewählte Stücke für Kontrabass und Klavier [music] / Giovanni Bottesini; nach den Quellen herausgegeben und eingerichtet von Klaus Trumpf. Leipzig: VEB Deutscher Verlag für Musik, 1984, 24,27.

12 Isaac Trapkus, ed., "Double Bass Concerto, Op.3 (Koussevitzky, Serge)," IMSLP, 2021, View Website, 2.

Bradetich, Jeff. University of North Texas, Interview with the Author, 20 November 2020.

Bradetich, Jeff. 2009. Double Bass—The Ultimate Challenge. USA Idaho: Music for All to Hear.

Brun, Paul. 2000. A New History of the Double Bass. Villeneuve d'Ascq: P. Brun Productions.

Dragonetti, Domenico. Concerto pour Contrebasse à Cordes et Piano. Paris: Alphonse Leduc, 1925.

Eisenberg, Maurice. 1966. Cello Playing of Today. Great Britain: Lavender Publications.

Giovanni Bottesini, Klaus Trumpf. Ausgewählte Stücke für Kontrabass und Klavier [music] / Giovanni Bottesini; nach den Quellen herausgegeben und eingerichtet von Klaus Trumpf. Leipzig: VEB Deutscher Verlag für Musik, 1984.

Möchel, Kurt B. Zweck-Etüden für Kontrabass = Etudes Pratiques Pour la Contrebasse = Special Studies for Double Bass. Mainz: B. Schott's Söhne, 1931.

Nanny, Edouard, Rodolphe Kreutzer, and Federigo Fiorillo. 1921. Études de Kreutzer et de Fiorillo. Paris: Alphonse Leduc.

Nanny, Edouard. 1920. Complete Method for the Four and Five Stringed Double Bass. Paris: Alphonse Leduc.

Sperger, Johann Matthias. Konzert D-dur Nr. 15 für Kontrabass und Orchester. Arranged for double bass and piano by Michinori Bunya. Leipzig: Friedrich Hofmeister, 1999.

Tortellier, Paul. 1988. How I Play, How I Teach. London: Chester Music.

Trapkus, Isaac, ed. "Double Bass Concerto, Op.3 (Koussevitzky, Serge)." IMSLP, 2021. View Website.

Born in 1981 in Germany, Irmak Sabuncu began music at the age of 10 with piano lessons. He then began double bass training in 1996 at Çukurova University, Turkey in Prof. Tahir Sümer's class. He continued his education in 1998 in Dokuz Eylül University, State Conservatory, Turkey. In 2005, he graduated from Prof. Tahir Sümer's double bass class. Irmak was accepted to Zurich University of the Arts (Zürcher Hochschule der Künste) in 2006. For the years of 2009 and 2010, he pursued his Konzert Diplom and CAS (Certificate of Advanced Studies in Music Performance) diplomas, respectively in the class Prof. Duncan McTier. Subsequently, he was accepted to the class of Prof. Bozo Paradzik in 2010 for pursuing Orchester Diplom in Musikhochschule Luzern, Switzerland and he completed this degree in 2013. Irmak also completed his practical training in Bern Symphony Orchestra (Switzerland) in 2011. He participated in Prof. Zakhar Bron's chamber orchestra.

In 2010, he attended to Sion Festival in Zhdk Strings Chamber Orchestra with Prof. Rudolf Koelman and Shlomo Mintz also participated "Herbst in der Helferei" (Zürich) Festival with Zürich Stringendo Chamber Orchestra throughout the four years (2008, 2009, 2010, and 2011). He took part in Winterthur Musikkollegium, Collegium Novum Zürich, Zürcher Kammerorchester, Berner Kammerorchester as well as Musikkollegium Basel orchestras. He attended workshop and master classes of Prof. Tahir Sümer, Prof. Bozo Paradzik, Franco Petracchi, Gary Karr, and Massimo Giorgi. During 2012-2017, he worked as a double bass lecturer at the Mersin University, State Conservatory, and teaching fellow in the University of North Texas from 2017 to 2020.

Irmak obtained his D.M.A. from the class of Professor Jeff Bradetich at the University of North Texas in May 2021.

© 2003 - 2026 International Society of Bassists. All rights reserved.

Items appearing in the OJBR may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the International Society of Bassists, and advance notification of the editors of the OJBR.

Any redistributed form of items published in the OJBR must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in The Online Journal of Bass Research in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] in [MONTH/YEAR], and it is republished here with the written permission of the International Society of Bassists.

Libraries may archive issues of OJBR in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of the OJBR and the International Society of Bassists.

Citations to articles from OJBR should include the URL as found at the beginning of the article and the paragraph number; for example:

Volume 3

Alexandre Ritter, "Franco Petracchi and the Divertimento Concertante Per Contrabbasso E Orchestra by Nino Rota: A Successful Collaboration Between Composer And Performer" Online Journal of Bass Research 3 (2012), <http://www.ojbr.com/volume-3-number-1.asp>, par. 1.2.Volume 2

Shanon P. Zusman, "A Critical Review of Studies in Italian Sacred and Instrumental Music in the 17th Century by Stephen Bonta, Burlington, VT: Ashgate Publishing Co., 2003." Online Journal of Bass Research 2 (2004), <http://www.ojbr.com/volume-2-number-1.asp>, par. 1.2.Volume 1

Michael D. Greenberg, "Perfecting the Storm: The Rise of the Double Bass in France, 1701-1815," Online Journal of Bass Research 1 (2003) <http://www.ojbr.com/volume-1-complete.asp>, par. 1.2.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.