Volume 17 of the OJBR presents Learning Strategies for Complex Rhythms: Approaching Richard Barrett's splinter for contrabass solo (2018-2022) by Kathryn Schulmeister.

Kathryn Schulmeister's award-winning article examines the rhythmic complexities of Richard Barrett's solo double bass work splinter, in meticulous and vivid detail. More importantly, the article discusses approaches to analyzing, preparing, and practicing the difficult rhythmic passages, in addition to discussing the theoretical and interpretive underpinnings for those approaches. Fans of Brian Ferneyhough's Trittico per G.S. (1989) for solo double bass and Theraps (1976) by Iannis Xenakis would also be interested in learning about Barrett's splinter. Also, any musical practitioner in any genre of music who has taken on or is currently taking on the challenge of performing very complex rhythmic passages in their solo and/or orchestral repertoire would be interested in the solutions that the author proposes.

The article was the winner of the 2022 ISB Research Competition, in the Student Division, while the author was a graduate student at the University of California San Diego.

Kathryn Schulmeister is a member of several contemporary music ensembles including the renowned Australian ELISION Ensemble, Fonema Consort (NYC), and the Echoi Ensemble (LA). She has performed as a guest artist with various adventurous international ensembles such as Klangforum Wien, Ensemble MusikFabrik, Delirium Musicum, Ensemble Dal Niente, and Ensemble Vertixe Sonora. Kathryn served as a core member of the Hawaii Symphony Orchestra for three consecutive seasons from 2014-2017 and has performed with the Ojai Festival Orchestra, Phoenix Symphony, New West Symphony, California Chamber Orchestra, Lucerne Festival Alumni Orchestra, Pacific Lyric Opera, Maui Chamber Orchestra, and Hawaii Opera Theater. Kathryn received her Doctor of Musical Arts degree in Contemporary Music Performance from the University of California San Diego, Master of Music degree from McGill University, and Bachelor of Music degree from the New England Conservatory of Music.

How do we learn to perform contemporary scores with complex rhythms? For the past five years as a graduate student with a specialization in contemporary music performance, I have devoted part of my performance practice to designing my own unique methodologies to address the myriad of interpretive challenges that arise in the learning processes of innovative compositional scores. To learn these scores, I developed practice strategies that depart from the approaches I cultivated during my classical conservatory training. In this paper, I will introduce and discuss Richard Barrett's new work for solo double bass, splinter (2021), and explain how I strategized the deciphering of complex rhythmic notation with multiple methods of rhythmic translation. The learning strategies included in this paper are by no means meant to be exhaustive nor are they intended to serve as pedagogical texts. Rather, this paper is offered as a contribution to the ongoing discussion of how a performer could consider designing their learning methods to fit the conceptual, musical, and technical demands of new works that have limited or no performance history.

Richard Barrett (b. 1959 in Swansea) is an internationally acclaimed composer, performer, and scholar with a prolific output of innovative compositions for a variety of musical ensemble formats and technologies. His published writings on his own creative practice and research in contemporary musical thinking illuminate the perspective from which his compositions are conceived. His work encompasses a wide variety of approaches to composing for contemporary musicians, including graphic scores for structured improvisations, hybrid scores that include standard notation and guided improvisational sections, and completely traditionally notated scores that feature extraordinary amounts of detailed and intellectually challenging material for performers to interpret both in terms of rhythmic and pitch content. Barrett also performs as a computer musician and improviser, which influences his compositional process and areas of interest. As a Welsh composer emerging in the late twentieth century, he has been both influenced by and associated with a cohort of British composers committed to a radical approach to composition, often referred to controversially as the 'New Complexity'1.

Although this trend of 'New Complexity' in music composition is often associated with the superficial appearance of their meticulously notated scores which pose monumental challenges for performers to interpret, musicologist Richard Toop argues that the true commonality among the artists involved in this movement lies in their shared deeper sense of motivation, of their experience as musicians living on the 'fringes' of Europe, outsiders in relation to the dominant European contemporary musical traditions in Germany and France. In his often-referenced article "Four Facets of the New Complexity", Toop writes:

I think the key lies in [James] Dillon's comment:

I tend to think that one of the reasons I found Xenakis fascinating was that we both come from the fringes of Europe.

The essence of all four composers [Michael Finnissy, James Dillon, Chris Dench and Richard Barrett], I believe, lies in precisely this 'fringe' notion, interpreted not in a negative, self-disparaging sense, but in a positive (albeit somewhat predatory) one. In The Theatre and its Double, Artaud claims that European theatre can only be revitalised by the radical incursion of non-European conventions and ways of thinking. He had in mind the traditions of Asian theatre; but for our four composers, as it seems to me, Britain too is sufficiently 'remote' for the invasion/assault to be artistically productive.2

As Toop suggests, the shared qualities of complexity seen in the notation of these composers is more indicative of a shared radical philosophical approach to composition rather than a shared artistic or aesthetic concept.

On the visual surface, Barrett's scores share notational characteristics with a whole host of compositions from various composers which feature assiduously notated rhythmic material, often utilizing multiple overlays of polyrhythmic ratios and irrational subdivisions of the governing tempo for the work. The composer most often associated with this trend in complex notation is British composer Brian Ferneyhough (b. 1943, Coventry), a mentor of Barrett's and a clear influence on Barrett in terms of radical instrumental composition.3 It must be noted, however, that each individual composer has their own unique artistic concepts and priorities, and the superficial similarities in their notational systems do not necessarily justify similar approaches to their interpretation and performance. For example, Ferneyhough's intention with his approach to writing rhythmic material is fundamentally different from Barrett's, and therefore could be considered differently from an interpretation and performance standpoint. As Toop articulates:

In Ferneyhough's work, though, the irrational values are generally a means of redefining the overall rhythmic flow from one bar (or beat) to the next and merely provide the framework for complexly sculpted internal rhythms. With the younger composers (and most drastically, perhaps, with Chris Dench) a more obvious model is Xenakis, and the aim is usually, as with Xenakis, to create different simultaneous pulses which are usually periodic and, far from seeking to redefine motion at the barlines, these periodic groups habitually go across them.4

As Toop points out, Ferneyhough's rhythmic ideas are often molded to create elegant complex relationships to the consistent pulse and profile of the meters with which he composes, while some of the younger generation composers such as Barrett employ compositional processes more similar to the stochastic methods of Greek composer Iannis Xenakis (1922-2001) and German composer Karlheinz Stockhausen (1928-2007), with their shared interest in generating varied simultaneous tempi within a piece. On the visual surface of the notated score, their collective works may appear similar to Ferneyhough's, but conceptually each composer works with their own personal ideas of how rhythm can be imagined.

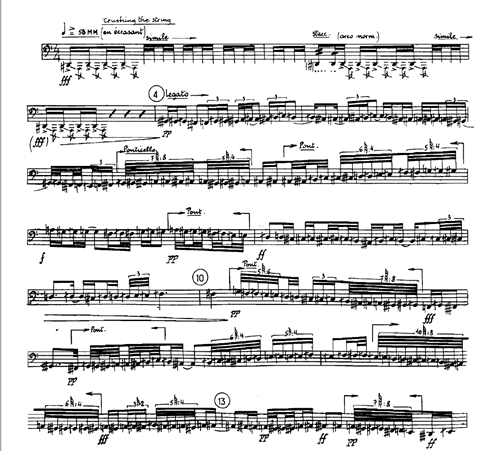

Both Ferneyhough and Xenakis have composed significant solo works for the double bass, Trittico per G.S. (Ferneyhough, 1989) and Theraps (Xenakis, 1976). While both pieces pose tremendous challenges to the performer in terms of the rhythmic interpretation and technical virtuosity required to perform the demands of these works, the nature of how rhythmic ideas (temporal relationships) are conceptualized within each piece differ significantly. In Xenakis' Theraps (1976) for solo contrabass, Xenakis uses stochastic principals to generate varied tempi within the work, which he overlays on a consistent meter of 4/4 for most of the piece (see figure 1).5

Figure 1: Xenakis: Theraps (1976)for solo contrabass, measures 1-13

Xenakis creates a single musical line which morphs through acceleration and deceleration as it traverses the pitch range of the contrabass. Although the rhythmic material in Theraps is complex in that it frequently features bracketed polyrhythms within single measures, it doesn't necessarily relate to the traditional profile of the 4/4 meter (i.e., it doesn't favor traditionally strong or weak beats).6 I assert that Xenakis is rather using the 4/4 meter as a convenient method to create a consistently measured extended temporal canvas upon which to articulate varied tempi generated by his stochastic theory and expressed through polyrhythmic subdivisions of the beat.

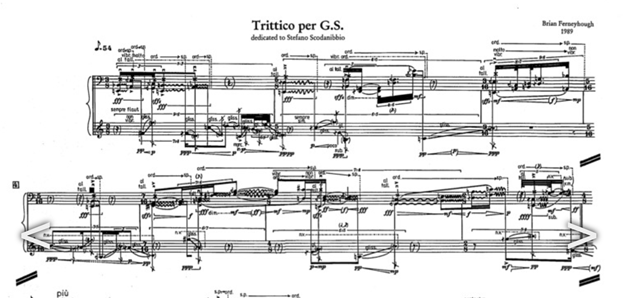

In contrast, Ferneyhough's Trittico per G.S. (1989) for solo contrabass presents an approach to rhythm that is not concisely linear but rather complex in its superimposition of multiple layers of rhythmic lines that intentionally disrupt and interfere with each other, all written within rhythmic relationships to carefully constructed meters that vary nearly every measure (see figure 2).

Figure 2: Ferneyhough: Trittico per G.S. (1989) for solo contrabass, measures 1-7

In Trittico per G.S., Ferneyhough creates intricately sculpted rhythmic phrases within the inherited traditions of a metric framework. In the authoritative article on the performance of Ferneyhough's iconic solo percussion work, Bone Alphabet (1991-92), percussionist Steven Schick explains that Ferneyhough does not conceive of the rhythmic material within the work as constantly varying tempi. Consequently, Ferneyhough advised the interpretation process to not involve the translation of polyrhythmic ratios into tempo values as a learning method to solve the rhythmic challenges.

On this subject, Schick writes:

In my conversations with Ferneyhough, he has clearly indicated his opposition to such tempo-based solutions to polyrhythmic composites. He maintained that polyrhythms conceived as modulations of speed cause a reorientation of the strong and weak beats that lend metric sense to a given passage.7

Schick's insight and Ferneyhough's scores both suggest that an artistic interpretation of rhythm within a Ferneyhough score may be dealt with differently than how one interprets rhythm in a Xenakis score. Although some notable complex rhythm experts including Edwin Harkins insightfully point out that elements of meter, tempo, and rhythm are theoretically equally interchangeable in how they can be notated and intellectualized8, Ferneyhough's sentiment in his conversations with Schick and the clear intentions of the principles guiding the compositional processes of Xenakis and Barrett suggest there is room for nuanced and individualized approaches in building personal interpretations of these varied pieces. In other words, there are multiple strategies that could be employed to realize the rhythmic challenges of these works, and I argue that it's useful to consider the artistic inspirations and conceptual intentions of individual composers when deciding how to navigate the process of learning and performing their works.

In Barrett's recent book publication, Music of Possibility, Barrett writes that his approach to composition is inspired by a drive to use music as a means of imagining new horizons and challenging our perceived artistic limitations, both within the musical works themselves and beyond. In reference to his own artistic priorities, Barrett writes:

My text was entitled "The Possibility of Music", but proposed the idea of a "music of possibility", with the intention of characterising a music which might seem a small and insignificant phenomenon within the musical world as a whole, but which is actually in some transdimensional way "larger than the profit-friendly musics which seem to surround it, because of the breadth of its imaginative horizons, and the freedom we have, both as musicians and as listeners, to explore them. This is one of the few real freedoms available to us, after all." And it might serve, in however small a role, as some kind of emancipatory model for other areas of life.9

Barrett's proclamation of imaginative freedom within the music he composes indicates that he intentionally departs from inherited traditions of Western art music in meaningful ways, which ideally creates a sense of exploratory freedom for the performer and the listener to experience in his music. This is a critical point for a performer to understand in developing learning strategies for Barrett's work. It must be understood from the beginning of the learning process that the experience of realizing and understanding the score will push the performer to venture into learning processes that prior traditional training may not have entirely prepared them for.

Regarding learning rhythmically complex contemporary scores, British pianist and contemporary music scholar Ian Pace writes:

Interpretative strategies need to be continually re-examined when learning a new piece or re-learning an old one. But at heart they represent a strategy of resistance in performance; resistance towards certain ideological assumptions that entail absorption of musical works into the culture industry. [...] This type of musical aesthetic, whereby musical works exist in a critical and dialectical relationship to wider experiences and consciousness (and by implication to the world), is to my mind one of the most important ways in which music can become more than passive entertainment. Looking hard at the relationship between notation, metre and time, is one of the most powerful ways of enacting this in practice.10

Pace articulates how the act of strategizing the learning process for an interpretation which deliberately resists the gravity of inherited cultural assumptions has a palpable artistic value that comes across in performance, ideally by stimulating the audience into having an engaging, critical experience rather than solely passive listening. Pace further posits that the primary purpose of this type of music is to call into question the act of making music, the consciousness of the present moment, and to invigorate the senses with the experience of an unfamiliar territory. Therefore, the challenges posed by learning such a rhythmically complex score offer the performer the opportunity to create a unique learning strategy which intentionally departs from their prior training and questions the inherited cultural assumptions of how rhythm can be learned and performed.

As a composer and performer Barrett has experimented with various points of departure from the traditions of Western art music, with emphases on the four practices that he argues are of the most consequence in the development of twentieth century music:

1.2 the development of systematic composition methods;

1.3 the growing use of electronic and digital technology;

1.4 the evolution of improvisation towards independence from pre-existent stylistic/structural frameworks

1.5 a widening awareness of the geographical, historical and political dimensions of music.11

In approaching the learning process for Barrett's splinter (2018-2022) for solo double bass, I argue that it is useful to consider which innovations Barrett applies in this specific composition and to be aware of his larger perspective on music making. For example, although the development of systematic composition methods defines the most critical aspects of splinter as an innovative contemporary work, I would argue that understanding Barrett's performance practice as a computer musician and improviser could also influence the interpretation and performance of this work. In other words, although the focus of my learning process deals with the challenges of the score that emerge from systematic compositional processes, in the realization of the interpretation I exercise the right to make interpretive choices given my understanding of the intentions of the composer, which are informed by his various artistic values and practices. In practice, this means that I understand that the intention for his music is to evoke a sense of malleability and freedom in relation to the perception of the rhythmic material within the work, even though the score features meticulously notated highly complex rhythmic information that might appear rigid at a first glance.

splinter (2018-2022) for solo double bass is directly related to one of Barrett's in-progress works for large-scale ensemble titled PSYCHE12. The conglomerate work will feature several solo and chamber ensemble works that feature individual performers as well as small ensembles and provide short concert pieces that can be performed independently from the PSYCHE complete work. In the program notes for this work, Barrett writes: "splinter is derived from the solo part of elsewhen for contrabass and ensemble, which itself forms part of the conglomerate composition PSYCHE."13

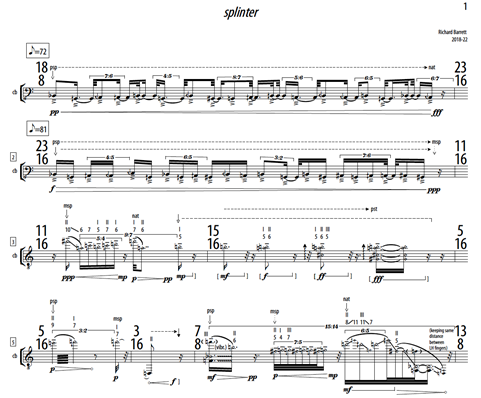

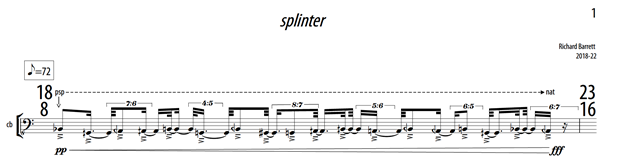

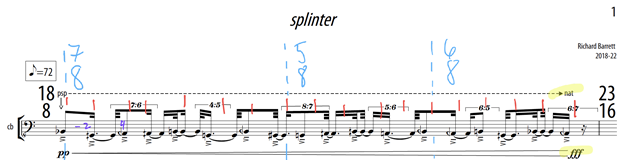

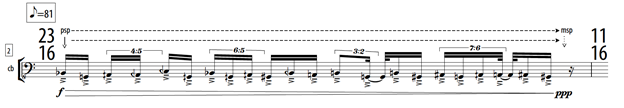

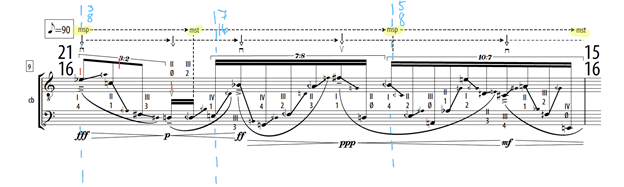

Figure 3: Barrett: splinter (2018-2022) for contrabass solo, measures 1-7

At a first glance, the score for splinter (see figure 3)appears to be written in a language that I already know fluently and understand, a notation system which I have studied and practiced reading and interpreting for well over 20 years, with rigorous conservatory training at elite higher learning music institutions: standard Western music notation. Barrett's score, however, uses the Western music notation system to represent highly detailed layers of complex rhythmic information in such a way that challenges a performer in their ability to intellectually understand and technically execute the prescribed rhythmic material. Not only is the music not sight-readable in the sense that it is impossible to do a casual "read-through"14 of the piece (due to the rhythmic challenges), but it also requires a significant amount of creative deciphering, time, and attention to intellectually understand the notated material of each individual bar. Although it's quite normal to come across passages in contemporary music that require extensive practice to execute, it's another challenge altogether to have to solve the rhythmic problems of each individual bar just to simply conceive of how the rhythm might sound.

Although the pitch material of splinter similarly presents unique challenges to the performer, Barrett's score is remarkable in its successful conception of the physical parameters of the double bass and how the notes will fit within a player's hand position. Barrett even goes so far as to notate specific fingerings for passages that move about the full range instrument with rapid speed and varied durations. In this sense, given that Barrett's fingerings work well, he makes clear in his score that he has thoughtfully studied the instrument while writing exceptionally challenge music. His notated fingerings expedite the time-consuming process of forming personal fingerings for the work, a process which requires trial and error and potentially could require countless hours in addition to the numerous hours required to decipher the rhythmic material.

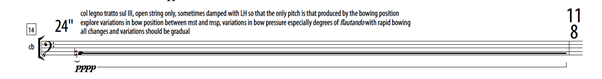

Aside from the gargantuan tasks of learning the rhythmic and pitch material of splinter, there are a select few moments of improvisational exploration that contribute to the form of the piece and provide a sense of poetic gesture to the seemingly ultra-rational score. At four distinct moments in the work, the scores indicates for the performer to explore gradual variations in timbre (see figure 4) in an unmetered duration (between 24-50") in a manner which Barrett describes as "...shouldn't be separated from the sounds around them, but should emerge as if taking place continuously below the music's audible surface."15 This instruction not only evokes a highly imaginative soundscape for the performer to draw upon in shaping their interpretation, but also suggests to the performer that the same exploratory spirit could be evoked in character from the metered material that makes up the majority of the work.

Figure 4: Barrett: splinter, measure 14

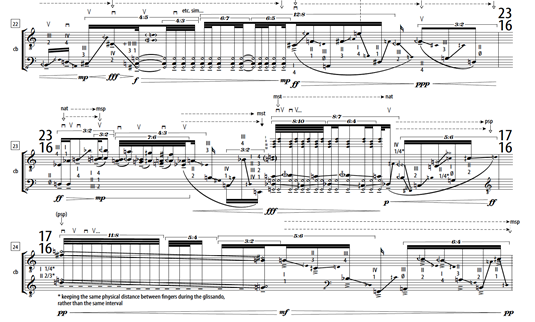

In several key moments of the work, Barrett composes a few passages for the bassist to perform three and/or four simultaneous musical lines across three and/or four strings, which approaches the brink of being technically impossible, however there are strategies for creating the effect of playing across the four strings. Barrett's score invites this sort of strategy in that it clearly notates parts of the lines that should be favored or played on certain strings, and exactly when to alternate the bow between different combinations of strings (see figure 5, measure 23). Although Barrett writes glissandi to be performed with the left hand, the alternating articulations of the right hand (the bow) will render the sound of the passage somewhat indeterminate and therefore gestural in form rather than strictly precise. The result is a unique timbral gesture that inhabits a musical space somewhere between the hyper precise single line notation that makes up most of the piece and the few unmetered open exploratory passages.

Figure 5: Barrett: splinter, measures 22-24

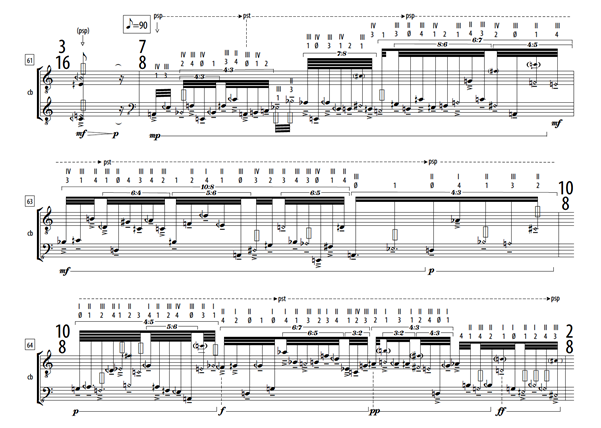

Overall, then, I conceive of splinter as an 8-minute solo piece with five sections separated by unmeasured periods of timbral exploration. The first section (from measures 1-14) articulates a single melodic line, which frenetically inhabits a flexible rhythmic grid and expresses the pitch and dynamic range of the bass with rapid fluidity and agility, often with brief yet sizable glissandi. The second section (from measures 15-24) departs from the linear nature of the first section by articulating short gestures that chaotically alternate between different registers of the instrument. The second section also features moments where short gestures are rapidly performed by alternating strings within a close range of pitch, and introduces a variety of timbres, rhythmic, and gestural figures that contrast the singular nature of the first section (see figure 5). Although the second section also features glissandi, much more of the material in the second section is focused on the complex sonorities that emerge from the playing of multiple strings simultaneously and or back and forth in close succession. In the third section (measures 26-32), the texture of the work initially thins out to soft articulations of harmonics high in the double bass pitch range. In the middle of the third section, the score gives the performer an extensive opportunity to explore the triple stop of playing clustered pitches across the second, third, and fourth strings. The third section finishes with another flourish of high harmonics in fleeting glissandi gestures. The fourth section (measures 34-58) introduces two new types of material: fast slurred lines in stepwise motion or alternating thirds (with various quarter tones), and repeated alternations between multiphonics with slight variations and articulations of the open fourth string. As the fourth section progresses, the material becomes more varied and reminiscent of the prior sections save for the presence of single isolated articulations of varying textures including pizzicati16 and accented double stop harmonics17. The fifth and final section (measures 59-75) of splinter integrates multiphonics into a continuous stream of rapidly alternating notes which dramatically alter with varying intervallic relationships. The energy output required to perform this section suggests that measures 62-64 (see figure 6) are a climactic point of expression for the entire work. Measures 65 to the end could be interpreted as a coda, with brief references to gestures and material introduced earlier in the work, and a final continuously descending passage spanning the very last six measures of the work.

Figure 6: Barrett splinter, measures 62-64

In the sections that follow, I will explain how I used multiple processes of rhythmic translation as a primary learning strategy for creating my performance interpretation of Barrett's splinter.

At the start of my learning process, I found that the most immediate and acute challenge of preparing an interpretation of Barrett's splinter is learning to understand and technically perform the rhythmic material in the score. I say this because the notes themselves are not unknown values to me, and at the beginning of the learning process I immediately understood how to play the notes on the score, but I did not immediately understand how to approach representing the rhythms.

The rhythmic challenges posed by Barrett's score far surpass the traditional range of complexity that is typically encountered in contemporary music, although not unprecedented as earlier discussed in this paper. The challenge lies in the multiple layers of rhythmic information within the score that the performer must decipher, intellectually understand, and physically be able to execute with an accuracy that can be perceivable by a listener. As percussionist Professor Steven Schick writes in his essay on learning Ferneyhough's notoriously rhythmically complex Bone Alphabet: "Learning is measured by a palpable change of state: you have learned if you can do, think, realize, or notice something that you formerly could not."18 As Schick eloquently points out, the goal for my learning process with splinter is to be able to intellectualize and physically represent the material on the score. The research question lies in how to get to the point of understanding and execution, and there are multiple paths that one could take in getting there.

Since the starting point of the learning process creates a situation where a performer cannot initially intellectually understand and therefore cannot physically represent the rhythmic material on the score, the learning process must take on a strategy of rhythmic translation for the performer to be able to understand and learn to reproduce the information. Rhythmic translation, meaning to express the rhythms notated into different, more comprehensible terms19, can work in different ways. As complex rhythm expert Edwin Harkins explains, meter, tempo, and notated rhythm can all theoretically be interchangeable to produce the same sounding result.20 Therefore, a performer could use this knowledge to translate one of these terms into another. For example, a performer may not be able to simultaneously calculate multiple layers of polyrhythmic relationships, but they could translate a single rhythmic ratio into a tempo value equivalent calculated to accurately represent one layer of polyrhythmic information.

In the case of addressing the rhythmic challenges of Barrett's splinter, I decided to use multiple methods of rhythmic translation to help me learn to interpret and perform the rhythmic material. The methods I used included translating meters of single measures into multiple shorter sub-measures, translating polyrhythmic ratios into tempi, and translating the durations of groups of notes into rhythmic subdivisions of tempi. All these methods combined allowed me to strategize how I would learn to translate the rhythms of the score into my performance on the contrabass. In the section that follows, I will provide detailed examples of how these specific methods of rhythmic translation worked in deciphering the rhythmic challenges in Barrett's splinter.

Although these processes of rhythmic translation may seem to conceptually diverge from the ideas presented in the musical score, Barrett himself thinks of the musical ideas in terms of tempi relationships, and I would argue this approach is not only efficient and precise in the learning process for the performer, but also philosophically aligned with Barrett's intention for the rhythmic profile of the work. Regarding his compositional approach to rhythm, Barrett writes:

The presence of "complex" or "irrational" rhythmical subdivisions, sometimes nested within each other, is a frequent (although not omnipresent) feature of my notated compositions. Usually, they function to generate flexible rhythmical grids, [...] where streams of activity (different instrumental parts, or different voices or layers within a single part) might be coordinated with or discoordinated from one another to varying degrees.21

As Barrett writes, his compositional intention is to create flexible rhythmic subdivisional grids which allow for moments of coordination, non-coordination, and heterophony among multiple ensemble parts or within a complex/polyphonic solo instrumental part. Barrett applies two principal systems to create this musical structure: a hierarchical approach and a non-hierarchical approach. For the hierarchical approach, Barrett takes inspiration from Clarence Barlow's book, Bus Journey to Parametron (1980), and systematically generates a probability gradient22 between simple subdivisional ratios, which are then expressed as metric modulations of a consistent pulse. For his non-hierarchical approach, Barrett composes subdivided durations that are distinct in tempo from their adjacent notes, using a logarithmic scale of durational values to generate rhythmic values. In both cases, the perceivable musical effect is a sense of rapidly changing tempi, from note to note and from measure to measure as well.

With this understanding of Barrett's compositional intentions, I needed to decide how I would strategize learning and performing the score as it maps highly detailed notated material onto a flexible rhythmic subdivisional grid. I needed to find a way to communicate a common pulse and a sense of notes flexibly aligning with or swerving around that common pulse in a highly varied and unpredictable way for the listener to potentially be able to perceive. I believe that Barrett is inspired by the freedom of movement that exists in the natural world and emulating that with his highly complex rhythmic material. Therefore, my task as a learner was to find a way to be accountable for both the rigorous structure that the score provides while also embodying the spirit of freedom and possibility that inspires Barrett's work.

Throughout splinter, many of the measures contain a relatively large number of beats within an odd meter and are challenging to intellectually track in performance given the additional and more pressing task of interpreting the immense amount of rhythmic information written within the lengthy individual measures. For example, in the very first measure of splinter, the meter of the bar is 18/8 (see figure 7), which on its own isn't necessarily a difficult meter for a performer to intellectualize, however given that Barrett intends to create flexible subdivisional grids for rhythm in his work, it naturally follows that after the first note of the piece (which begins on the first beat of the measure, or the "downbeat"), none of the subsequent notes in the measure are articulated on a subsequent eighth note beat of the measure.

Figure 7: Barrett: splinter,measure 1

In theory, the rhythm problems that present themselves in measures such as the first measure could be manageably addressed with traditional learning methods of breaking down the measure into chunks and learning the polyrhythmic relationships in isolation. This process could then be followed by a process of embodying the rhythmic material and committing the material to memory, slowly assembling the rhythmic material of the measure together in a string of memorized events practiced in isolation. The reality of the learning process, however, proved to be more challenging than a theoretical one. In my initial practice sessions and meetings with my advisor, I rehearsed with a custom made click track that featured 18 beats for the first measure, and I would frequently get lost in the middle of the measure and end up adding or subtracting a beat at some point in the measure. It was clear from the beginning of the learning process that I needed to find a solution to help me train my ability to track the rhythm accurately throughout the measure of 18 beats.

Tracking the 18/8 meter of the first measure became a performance challenge for me by the second eighth note of the bar, where most of succeeding notes are articulated not only in misalignment with the recurring pulse of the measure (the eighth note), but also with varying polyrhythmic relationships dictated by odd and irregular subdivisions of the common beat. By the end of the second beat of the first measure, the rhythm notated indicates a bracketed 7:6 relationship for the underlying rhythmic figure, meaning that the speed of the 32nd notes within that bracketed figure should be articulated within the timeframe of what would be equal to six 32nd notes at the governing tempo of the measure (in this case, an eighth note = 72bpm). Thus, the tempo of the bracketed figure has a relationship of 7:6 to the governing tempo of the measure. To understand and clearly execute the notated rhythm of this polyrhythmic relationship, the performer must not only keep track of the governing pulse of the measure and how each note relates to that pulse, but also intellectualize and physically mark the rhythmic tempi of the 7:6 relationship as it begins and ends on subdivisions of beats within the measure.

To begin the process of breaking down the material into smaller, more familiar, and thus more comprehensible information, I first made annotations to the score by dividing individual measures into smaller sub-measures. Therefore, I had to choose points to divide the measure into shorter sub-measures where I felt I could accurately relate to and align with as precisely as possible to new downbeats. This process took some trial and error, and at times, I would edit the decisions that I made if I found after a process of experimentation that the re-organization of the measure didn't work well. For the first measure of splinter, I decided to divide the measure into three shorter sub-measures. I translated 18/8 (original meter) into 7/8 + 5/8 + 6/8 (see figure 8). I also calculated how the polyrhythmic material in the measure would relate to the eighth note pulse of the measure and marked in my score an approximate visualization of where the eighth notes I would hear in the click track would align with my performance of the rhythm articulated on the page. Thankfully, Barrett takes great care and works with an extraordinary attention to detail in how accurately spaced his notation of rhythms appears on the page, so I found my annotations of writing in lines to mark the pulsed beats of the bar in line with the notational spacing of the score.

Figure 8: Barrett: splinter,measure 1, with annotations

Translating the meter of 18/8 into three shorter sub-measures allowed me to conceptualize the measure into more comprehensible chunks that I could track with more consistency and accuracy than I could with the original bar of 18/8. I made decisions about how to divide the bar based on several factors. Most importantly, I attempted to annotate and draw new bar lines where I believed I could most accurately align the rhythm written on the score with both my execution and the reference that I would use to monitor the accuracy (whether that was counting in my mind or using the external reference of a metronome/click track). By narrowing my focus on how I counted the rhythm within each bar, I immediately noticed that I was able to train my mind and body to be able to perform the notated rhythms with much more accuracy and consistently.

Although it may seem that translating the 18/8 meter into three shorter sub-measures could potentially alter the phrasing of the measure (it is clear from the score that Barrett intends to a create a gradual consistent build of dynamic intensity and timbral evolution from the precise start to finish of the measure), I argue that it's possible to take into consideration how the phrases are constructed, and to phrase across the annotated bar lines to make the intended shape of the composition. In the same way that one could connect the material of multiple measures under a phrasing line, a performer can make the full phrase of the 18/8 bar come to life while using the translated meters method to aid rhythmic accuracy.

This method of meter translation combined with the use of a custom made click track that I built for practicing and learning this piece (which I will discuss in much more detail in a subsequent section) allowed me to practice aligning certain rhythmic landmarks in the measure to gauge my accuracy and understanding of the rhythm as I practiced. Since I quickly found this method of meter translation to be effective, I continued to apply this process to the rest of splinter as was necessary, which given the hyper complexity of the piece proved to be necessary in nearly every measure of the work.

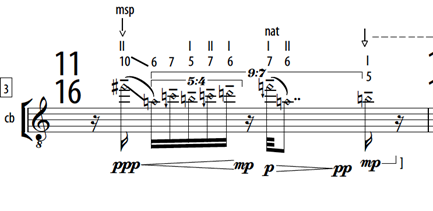

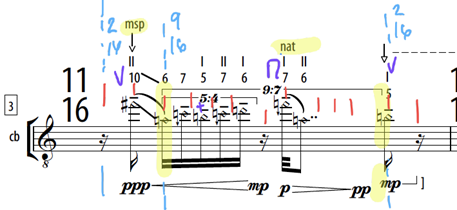

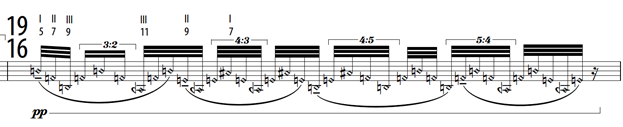

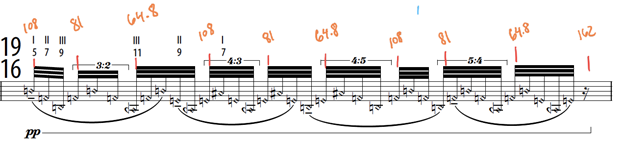

In the second measure of splinter, I applied nearly the exact same strategy that I applied in the first measure in that I broke down the long measure into three shorter sub-measures, however since the second bar has not only an odd meter but also a different subdivision of the pulse marked by the meter of the bar, my approach slightly altered to fit the exact rhythmic challenges of the second measure. In measure 2, the meter of the bar is 23/16 (see figure 9), however the tempo (indicated as a tempo change in the score) is expressed in eighth notes as an eighth is equal to 81bpm. Given that the tempo is both faster than the initial tempo of the piece and expressed in eighth notes, I decided to once again build the click track in eighth notes for the majority of the second measure, save for the very last three sixteenth notes of the bar, which need to be articulated as both smaller subdivisions and in an odd number to accommodate for the odd meter of the bar in sixteenth subdivisions.

Figure 9: Barrett: splinter, measure 2

Unlike in measure 1, I was able to determine two strategic internal points of measure 2 to align with downbeats of smaller sub-measures. From the original metric structure of 23/16, I translated measure 2 into three shorter sub-measures: 5/8 + 5/8+ 3/16 (see figure 10). In this case, the articulated beat of the third measure within the original measure 2 is measured in 16th notes, which works well in preparing the tempo for the following four measures, which all have unique lengths expressed with 16th note subdivisions of the same general governing tempo of an eighth note equals 81bpm.

Figure 10: Barrett: splinter, measure 2, with annotations

In the third measure of splinter, I continued to apply my method of breaking down measures into shorter sub-measures, and I also applied a new process of translating polyrhythmic material into distinct tempo values for part of the measure. Within measure 3 (see figure 11), there is a bracketed rhythm which indicates that the durational value of the nine notated 32nd notes within that bracket should occur within the exact time frame of seven 32nds at the governing tempo of the bar (in this case, eighth note = 81bpm, or sixteenth note = 162bpm).

Figure 11: Barrett: splinter, measure 3

Considering that not only would the 9:7 ratio be extremely challenging for me to intellectualize and technically perform, but also that within that bracket there is also another indicated polyrhythmic ratio of 5:4 (expressed in sixteenth notes), I decided to translate the 9:7 ratio to a new localized tempo of 208.3 bpm for the bracketed material. I calculated the new tempo by solving for the tempo variable of the bracketed 16th note as it relates in a 9:7 ratio to the original 16th note tempo of 162 bpm (calculated from the tempo marking of an eighth note is equal to 81 bpm). The equation to solve for the tempo (x) of the new 16th note within the bracketed material in measure 3 works as follows:

With the tempo of the 16ths within the bracketed material calculated, I could then learn the rhythmic material within the bracket as it relates to the new tempo of 208.3, rather than as a ratio of 9:7 to the original tempo of the measure. I combined this method of rhythmic translation, in this case rhythmic ratio to tempo, with the meter translation method. I divided measure 3 into three shorter sub-measures, 2/16 + 9/16(with the new tempo of 208.3) + 2/16 (see figure 12). To clarify, the two 2/16 measures that frame the 9/16 measure are both in the original tempo of the section, with the sixteenth note equal to 162 bpm. The reason that I decided to create two 2/16 bars instead of two 1/8 bars is because I needed to understand the sixteenth subdivision of the eighth note to perform the written material of the measure (i.e., I didn't have the temporal context to be able to perform those rhythms accurately without subdivision). In theory, I could memorize the eighth note tempo and perform a subdivision of that tempo but given that tempi for this piece change rapidly and nearly every measure, I felt it was more time efficient and technically accurate to train myself to think in sixteenth notes for this measure.

Figure 12: Barrett: splinter, measure 3, with annotations

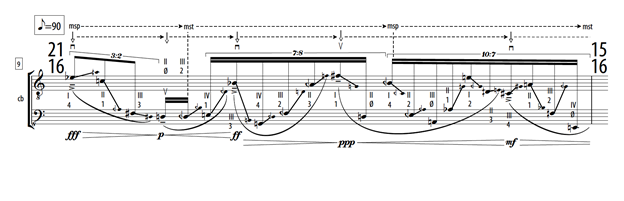

I applied the exact same method of rhythmic translation in measure 9 as I did in measure 3. Measure 9 (see figure 13), a measure of 21/16, features three separate brackets with varying rhythmic ratios.

Figure 13: Barrett: splinter,measure 9

Since the first ratio of 3:2 in terms of eighths notes is a standard polyrhythm that most musicians trained in Western music can perform by memory, I decided not to calculate the new tempi for the bracketed material at the beginning of the measure and instead grouped together the first three eighth note beats of the bar as the first sub-measure of measure 9. I then calculated the tempi of the new sixteenth notes within the following bracketed material with the ratios 9:7 and 10:7 and created sub-measures of 7/16 and 5/8 for the rest of measure 9, with the sub-measures beginning at the start of each of the bracketed sections. I decided to make the third sub-measure of measure 9 a 5/8 bar instead of a 10/16 bar because the tempo of the new sixteenth note was 257.2 bpm and I found it be more effective to subdivide the new eighth note pulse of 128.6 bpm as a reference tempo instead.24 Therefore, measure 9 (see figure 14) became a measure of 3/8 + 7/16(new tempo of 157.5) + 5/8 (new tempo of 128.6).

Figure 14: Barrett: splinter,measure 9 with annotations

The methods I've explained and exemplified with my analyses of measures 1, 2, 3, and 9, apply to most of the rhythmic challenges in splinter save for the cases in which I needed to apply the third method of rhythmic translation: translating the durations of groups of notes into rhythmic subdivisions of tempi. This third method first became necessary in strategizing an approach to learn the rhythmic material in measure 13, and subsequently became useful for more occasions in the subsequent parts of splinter. Measure 13 (see figure 15) presents an unprecedented rhythmic challenge within splinter in that it features a string of rapid notes (entirely made of variations of sixteenth and thirty-second notes) in groups of either odd numbers or within brackets notating polyrhythmic ratios to odd numbers of beats or subdivided beats within the bar. This presents a situation where neither a meter translation nor a translation of polyrhythmic ratio to tempo solves the problem of creating a comprehensible translation of the rhythmic material for the understanding and performance of the measure.

Figure 15: Barrett: splinter,measure 13

To solve this problem, I decided to use a process of translating the duration of groups of note values into tempi, in order for me to then be able to understand the note values as subdivisions of the calculated tempi, rather than in relation to the governing tempo of the bar. For the groups of notes that were direct subdivisions of the governing tempo (an eighth note equal to 81bpm), I grouped the notes together based on their notational barring (connection by notational stem) and calculated the total duration of the grouped notes. For example, the first three thirty-second notes of measure 13, each with an individual durational value of 324 bpm, could be instead interpreted as three equal subdivisions of a single beat of 108 in value (equal to a dotted sixteenth note). With this same process, I calculated the durational value of each group of notes within the measure, which solved the rhythmic problems of the bracketed polyrhythmic note groupings within the bar. For the note groupings written within the brackets of 4:3, 4:5, and 5:4, I calculated the durational value of each bracketed group, which then allowed me to interpret the rhythm as equal subdivisions of the calculated duration. For example, in the portion of the measure where there are four thirty-second notes written under a bracket that indicates the polyrhythmic ratio of 4:3, I calculated that the duration of the group of four notes needed to occur within the same duration as three thirty-second notes at the governing tempo of the bar (which also happens to be the same duration as the first note grouping of the measure), therefore, those four notes could be interpreted as four equal subdivisions of the pulse 108 bpm. I applied the same process of translating the duration of groups of note values into tempi for the entire measure and added an additional pulse for the duration of the sixteenth rest at the end of the measure (see figure 16). Measure 13, originally a 19/16 measure, became a measure of 10 beats of varying durations defined by rates of bpm: 108 + 81 + 64.8 + 108 + 81 + 64.8 + 108 + 81 + 64.8 + 162.

Figure 16: Barrett: splinter,measure 13 with annotations

In practice, I trained myself to memorize the tempi to perform the various subdivisions of unprecedented, individualized pulses. The most important feature of this solution, however, proved to be just the ability to intellectually understand how to approach the rhythms with confidence and measurable accuracy.

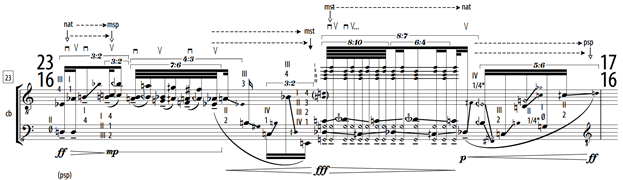

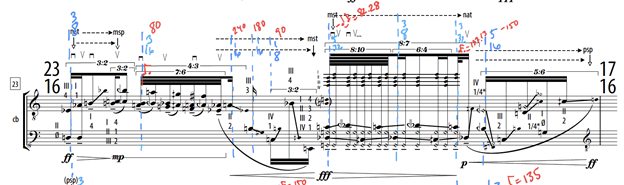

With the tools of multiple methods of rhythmic translation that I developed in the first part of splinter, I successfully integrated all three methods into measures that presented multifaceted rhythmic challenges and complexities. Measure 23 (see figure 17) is an example of some of the most complex rhythmic puzzles that need to be deciphered in splinter.

Figure 17: Barrett: splinter,measure 23

The primary challenge with measure 23 is that beyond the complexities of the playing techniques involved (multiple stops, microtones, artificial harmonics, etc.), there are multiple layers of polyrhythmic ratios nested within each other within an already challenging meter of 23/16. My strategy in deciphering the rhythmic material within measure 23 was to first address the nested polyrhythms of 8:10 and 6:4 within the bracketed polyrhythm of 8:7. Within this one bracket of material, I combined all three methods of rhythmic translation: First, I translated the 8:7 into three sub-measures of 5/32 + 6/4 + 3/23. Second, I calculated the durational value of the 8:10 grouping of notes (82.28bpm) and the value of the three thirty-second notes into a tempo value (137.13bpm) for a single beat that could then be subdivided by the notes within the groupings (82.28bpm), and third, I calculated the tempi for 6:4 material such that the eighth note pulse (154.3bpm) for the 3/8 sub-measure covering that grouping would reflect the accurate tempo given the multi-layered polyrhythmic information within the score. After organizing a strategy for this bracket of material, I then addressed the rest of the measure, which still featured numerous other complexities and challenges. Over the course of the entire measure, I translated the 23/16 meter into nine sub-measures (see figure 18) with the meters of 3/8 + 3/16 (click for whole bar equals 80bpm) + 1/16 (new tempo of 240) + 1/16 (new tempo of 180) + 1/8 (new tempo of 90) + 5/32 (click for whole bar equals 82.28bpm) + 3/8 (new tempo of 154.3) + 3/32 (click for whole bar equals 137.13bpm) + 5/16 (new tempo of 150).

Figure 18: Barrett: splinter,measure 23 with annotations

For the first bracketed material of the measure, I calculated the tempo of an eighth note in the 3:2 bracket as 135bpm, which helps with the subdivisions of the individual eighths within the bracket. In the second bracketed material of the bar, a 7:6 bracket is nested within the 4:3 bracket. In this case, I divided the 4:3 bracket into two sub-measures and solved the challenge of the nested 7:6 bracket by calculating the duration of the entire group of seven thirty-second notes, which came out to be equal to the durational value of 1 beat at 80 bpm. With this solution, I annotated the score by translating the 7:6 into a bar of 3/16 and decided to only reference the entire duration of the bar with one beat of 80bpm. Therefore, I could understand and practice interpreting the rhythm as seven equal subdivisions of a single beat of 80bpm. Given that the final sixteenth note within the 4:3 bracket is not a part of the 7:6 bracket, and it does not share a durational value nor a comprehensible relationship to the preceding rhythmic material, I decided to give that note a dedicated individual sub-measure and pulse (a sixteenth equal to 240bpm) calculated to reflect the 4:3 relationship to the tempo of the measure. I also decided to give the subsequent sixteenth note similar treatment and annotated the measure to include a second 1/16 measure, with a pulse reflecting a sixteenth note at the governing tempo of the measure, 180bpm. For the following 3:2 bracket, I decided to make the bracketed material fit within a sub-measure of 1/8 at the tempo of the measure, 90bpm. For the final bracketed segment of measure 23 I translated the 5:6 ratio to a new tempo of 150 for the sixteenth note within the bracketed material and annotated the score to make the last note grouping of the bar a sub-measure of 5/16.

I applied these three strategies of rhythmic translation (meter translation, polyrhythmic ratio translation, and durational grouping translation) to the entire score of Barrett's splinter and made decisions about which methods to use based on the specific challenges of each measure. In the sections that follow, I will describe how I built the click tracks for learning splinter, my practice strategies, and my conclusions about the learning process.

Once I had a designed a system for understanding the rhythmic material of splinter not only intellectually, but also potentially in way that I could attempt to perform on my instrument, it became clear that building a click track would be necessary to have a metronomic tool to practice with. Although a traditional metronome could produce close to all the tempi that I need for this piece, there are two major problems with using a traditional metronome: 1. A standard metronome would not be able to represent the fractional nature of the tempi calculated as translations of rhythmic ratios and 2. A standard metronome would have to be manually adjusted to change the tempo, therefore it would be impossible to practice the entire third measure, or any significant passage of the piece with a standard metronomic reference for accuracy. Although it could be argued that it isn't necessary to have a metronomic reference in order to memorize these tempi and put together an interpretation, given the accessibility of technology today, the hyper-precise nature of the notation, and the knowledge that Barrett intends for the tempi of individual notes, beats, and measures to be perceptibly varied, I decided to build a customized click track to help me learn the rhythms of splinter with the most precise and objectively measurable tools possible.

I realize that this approach of creating a click track may seem counterintuitive to the spirit of freedom and imaginative horizons that inspires Barrett's music, but I do not think the two ideas are mutually exclusive. In the same way that it is common to use a metronome for training a performer's understanding of a common pulse or as a tool to develop rhythmic accuracy, I too need to use an external resource to aid in my intellectual and physical training in my learning process of splinter.25

I made the decision to build my own click tracks for splinter as a tool not only for learning to intellectualize and technically perform the rhythmic material of this work, but also as a means for assessing my precision along the way. Given that Barrett intends to create perceivable changes in tempi in his creation of flexible rhythmic grids, I believe that my approach of translating complex rhythmic material into specific tempi applied locally to the measures, partial measures, or even single beats, is appropriate and effective for realizing the complex nature of this piece. Not only did my method of making a comprehensive click track for this work apply to creating the fully realized performance of the piece, but it also helped me design a practice strategy in which I could use the click tracks at various speeds to slowly intellectualize, embody, and learn the rhythmic material of the piece in small chunks. I then continued with a process of gradually stringing together larger segments of material and gradually increasing the tempo of the click track as I practiced bringing smaller sections up to the performance tempo.

I generated the click tracks by working with version 3.1.3 of Audacity®26 recording and editing software. There are several advantages to using a digital audio workstation to create a personal click track for practice purposes. The first is that you can easily manipulate and edit aspects of the click track, from determining the number of preparatory beats in a track to the frequencies27 of the downbeats (first beats) of individual measures vs the remaining beats. The second is that you can create rhythm tracks with fractional values, meaning that I could build a metronomic track for myself which included the details of my calculated solutions for rhythmic challenges, down to the 10th of a bpm. The third and most important advantage of this method is that it's possible to create a compilation of all the changing tempi and meters of the work; there is no technical limitation to creating a specific metronomic track for the entire work. In other words, with the combination of my rhythmic translation strategies and the computer technology of digital audio workstations, I could create a tool that could help me precisely gauge my understanding and performance of every rhythmic challenge posed in splinter. Some musicians might argue that this method seems to exert hyper rigid control over learning the rhythms of a score that was never intended to be performed by a computer. I, however, feel an immense relief and sense of empowerment in knowing that I have a method that will undoubtedly train my mind and body to precisely understand and perform the rhythmic material of splinter to the best of my ability. I am confident that the creativity in interpretation and performance is not sacrificed with the use of this learning strategy.

There are two main strategies that I developed to begin the process of mapping the rhythmic complexities of splinter onto my physical muscle memory to build my performance interpretation of this work. The first strategy was to meticulously plan how I would learn chunks of material, and how exactly I would put together progressively longer passages until I eventually could perform the entire work. The second strategy was using the computer application Transcribe!28 to easily manipulate the speed with which I could play the click track, making it possible to slow down and speed up the click track with subtle speed adjustments.

Given the extraordinary challenge that each individual measure presents in splinter, I decided it was necessary to make separate click tracks of every single individual measure to learn each measure separately, one at a time. Since it's helpful to be able to hear a few repeated beats of a given tempo before one begins to play in reference to that tempo, I created 4 preparatory beats for each individual click track of each measure. The preparatory beats always correspond to the tempo reference of the beginning of the bar, even if it's a translation from a polyrhythmic ratio.

Once I made individual click tracks for each measure, I then created click tracks for short passages of two to several measures, depending on the complexity of the material. For the click tracks for shorter passages, I also created four preparatory beats for each track with the same principle as applied in creating the click tracks for individual measures. I found that putting together short groups of measures to be doable once I had learned the individual measures thoroughly, since I had already started to develop an aural and muscular memory for the rhythmic challenges of each individual bar. After creating click tracks for shorter passages of several measures, I then created click tracks of longer passages, again determined from my analysis of the score, piece structure, and what I predicted to be manageable.

In practicing, I needed to be able to start at a very slow tempo, because it was physically impossible for me to immediately execute the rhythmic complexities of this work at full performance tempo. The transcription program Transcribe! became a significant practice tool to solve this problem. Intended as a transcription software for musicians to transcribe music from audio recordings, the program has a user-friendly feature that automatically loops imported audio tracks (in this case, the click track), and features a dial where the user can adjust the tempo of the recording from 1-100% of the normal playing speed. With these features combined, I could import a click track into the application, slow down the click track to a speed appropriate for starting to learn and practice (e.g., 50%), and keep the click track on a repeated loop with the built-in preparatory beats so I could repeat each measure or passage as many times as necessary. As simple as it may seem, I found this method incredibly useful and effective. Although there are no shortcuts to learning a complex piece of music, these tools helped me strategize an efficient method of learning that worked, and that I had confidence in. As efficient as this process is, I still could only manage to learn one or two measures a day as it on average took several hours to learn each individual measure.29 With this method I was able to successfully learn to perform the rhythmic challenges of splinter at performance tempo, and by using the click track, I had a measurable, objective scale to assess my performance accuracy.

Once I began to bring passages of material up to performance tempo, I began the process of video recording myself practicing. Listening and viewing recordings of myself playing through passages of the piece gave me a chance to both assess my performance and develop my understanding of splinter from an external point of view while I'm not splitting my attention between all the intellectual and technical demands of performing the music. If the process of practicing with a click track seems to not have much room for personal interpretation and creative expression, I believe that reviewing practice recordings provides the opportunity for more subtle and nuanced self-reflection in sound production (tone), phrasing, gesture, timbral quality, etc. I have not yet decided whether I would use a click track in a live performance or not, but in any case, I believe the method of practicing with a click track aids in the learning of Barrett's splinter.30

In conclusion, I found through my practice-based research and analysis that my methods of rhythmic translation and building of a click track worked successfully as a learning strategy for tackling the immense rhythmic demands of Barrett's splinter. Although I can understand a point of view that may critique my approach for being perhaps overly literal or mechanical in rhythmic interpretation, I personally do not see it that way. In my interpretation of splinter, I don't imagine that Barrett intends for the same gestures of romanticism that could be interpreted in other new complexity scores (such as those of Brian Ferneyhough), but rather that Barrett is inviting the performer to transcend to worlds of music previously unknown. Further, I imagine that I will develop an aural and physical muscle memory from extensive practice with the click tracks that will eventually lead me to experiment with performing an interpretation from memory in which I take more expressive liberties with the rhythmic material.

In writing on his compositional idea of radically idiomatic instrumentalism, Barrett writes:

The piece could then perhaps be viewed as a window into an entire repertoire that does not and will never exist, like a lost world of which a single artefact remains, an object which should be shaped so as somehow to invoke that whole world (in a related way to that in which serial music might attempt to invoke an entire configuration-space without having to map every point in it, as outlined above).31

From the musical score of splinter, and Barrett's statements on his own work, I believe that his score is an opportunity for a performer to push themselves intellectually, technically, and physically, to explore unknown musical territory.

1 Toop, Richard. "Four Facets of the New Complexity." Contact 32 (1988): 4-50.

2 Ibid.

3 Førisdal, Anders. "Radically Idiomatic Instrumental Practice in Works by Brian Ferneyhough." In Transformations of Musical Modernism, edited by Erling E. Guldbrandsen and Julian Johnson. Music since 1900, 279-98. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015.

4 Toop, Richard. "Four Facets of the New Complexity." Contact 32 (1988): 4-50.

5 Xenakis, Iannis. "Theraps." edited by Editions Salabert, 1976.

6 Latham, Alison. The Oxford Companion to Music. Revised First Edition. Edited by Alison Latham. Oxford University Press, 2011. "The beats are usually categorized according to where they fall in the bar: as 'weak' beats (the second and fourth in a four-beat bar, the second and third in a three-beat bar, or the second in a two-beat bar), or 'strong' beats (the first and, to a lesser degree, the third in a four-beat bar, and the first in a three-beat or a two-beat bar)."

7 Schick, S. The Percussionist's Art: Same Bed, Different Dreams. University of Rochester Press, 2006. P.104.

8 Vanoeveren, Ine. Tomorrow's Music in Practice Today. University Press Antwerp, 2018.

9 Barrett, Richard. Music of Possibility. Vision Edition, 2019. P.1.

10 Pace, Ian. "Notation, Time and the Performer's Relationship to the Score in Contemporary Music." In Unfolding Time. Studies in Temporality in Twentieth Century Music, 149-92: Leuven University Press, 2009. P. 191.

11 Barrett, Richard. Music of Possibility. Vision Edition, 2019. P.1-2.

12 PSYCHE was commissioned by the Australian ELISION Ensemble and will be premiered by the ensemble in the coming years.

13 Barrett, Richard. "splinter." 2018-2022.

14 In Pace's article on the relationship between a performer and a contemporary music score, Pace refers to the common practice of sight reading through a score at the beginning of a learning process as a chance for a performer to get an overall general sense of the piece. Pace, Ian. "Notation, Time and the Performer's Relationship to the Score in Contemporary Music." In Unfolding Time. Studies in Temporality in Twentieth Century Music, 149-92: Leuven University Press, 2009.

15 Barrett, Richard. "splinter." 2018-2022.

16 Barrett, Richard. "splinter." 2018-2022. Measure 46

17 Ibid. Measure 49.

18 Schick, S. "Learning Bone Alphabet". The Percussionist's Art: Same Bed, Different Dreams. University of Rochester Press, 2006. P.92.

19 Merriam-Webster. "Translate". Merriam-Webster Dictionary Online, 2022. https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/translate

20 Vanoeveren, Ine. Tomorrow's Music in Practice Today. University Press Antwerp, 2018.

21 Barrett, Richard. Music of Possibility. Vision Edition, 2019. P. 19-21.

22 In this context, a probability gradient refers to a rate of change in the durational value of notes.

23 208.3 is rounded up from the real solution of 208.285714

24 In practicing with a click track, I've learned that at a certain point, if the metronome click is too fast, it can be very difficult to respond and play along with. In some cases, a click track sounding the subdivision of a beat works best, and in others the more effective approach is to have the click mark groups of beats or subdivided beats.

25 It should be noted that both Steven Schick and Ian Pace argue against using click tracks for the preparation of works of different composers with similar rhythmic challenges to the ones found in Barrett's work because they believe that playing along with a computer-generated metronomic track could potentially rob the performer of the artifacts of humanity and freedom of timing in interpretation that should not only be allowed but also celebrated and emphasized in performance. I completely understand and respect this point of view, however I still feel that click tracks work well in aiding the learning process for Barrett's splinter.

26 Audacity® software is copyright © 1999-2021 Audacity Team. https://audacityteam.org/.

27 I found in my early practice sessions that I needed to adjust the frequencies of the click track such that the first beat of every measure was significantly higher than the remaining beats to aurally register and follow the click track as I simultaneously focused on performing the specific notes and techniques in splinter.

28 Transcribe! Version 8.75.2 for Mac. Copyright © 1998-2020 Seventh String Software. www.seventhstring.com

29 Given the time-consuming nature of this type of learning process, it is critical to organize a reasonable timeline for learning and preparing a performance interpretation of this type of work. I would advise planning for at least 3-6 months to learn splinter, although I would recommend 6-12 months as an ideal learning period.

30 It should be noted that ELISION, the ensemble with whom Barrett has had the longest continuing collaborative relationship with, plans to perform Barrett's chamber work for Double Bass, Percussion, and Harp with a click track in live performance (with Barrett's supervision). Therefore, I do not believe it is any sort of artistic/ethical taboo to perform with a click track in a live performance of Barrett's music.

31 Barrett, Richard. Music of Possibility. Vision Edition, 2019. P.27.

Barrett, Richard. "Improvisation Notes August 2005." Contemporary Music Review Vol. 25, Nos. 5/6 (October/December 2006) 403-04.

Barrett, Richard. "Splinter." 2018-2022.

Barrett, Richard. Music of Possibility. Vision Edition, 2019.

Barrett, Richard. "Richard Barrett." 2022, richardbarrettmusic.com.

Førisdal, Anders. "Radically Idiomatic Instrumental Practice in Works by Brian Ferneyhough." In Transformations of Musical Modernism, edited by Erling E. Guldbrandsen and Julian Johnson. Music since 1900, 279-98. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2015.

Fox, Christopher. "Music as Fiction: A Consideration of the Work of Richard Barrett." Contemporary Music Review 13, no. 1 (1995/01/01 1995): 147-57.

Ivan, Hewett, and Barrett Richard. "Fail Worse; Fail Better. Ivan Hewett on the Music of Richard Barrett." The Musical Times 135, no. 1813 (1994): 148-51.

Pace, Ian, Mark Delaere, Justin London, Pascal Decroupet, and Bruce Brubaker. "Notation, Time and the Performer's Relationship to the Score in Contemporary Music." In Unfolding Time. Studies in Temporality in Twentieth Century Music, 149-92: Leuven University Press, 2009.

Redgate, Roger. "Ferneyhough as Teacher." Contemporary Music Review 13, no. 1 (1995/01/01 1995): 19-21.

Schick, Steven. "Meandering." Chap. 12 in The Modern Percussion Revolution: Journeys of the Progressive Artist, edited by Kevin Lewis and Gustavo Aguilar. New York, NY: Routledge, 2014.

Schick, Steven. The Percussionist's Art: Same Bed, Different Dreams. University of Rochester Press, 2006.

Toop, Richard. "Four Facets of the New Complexity." Contact 32 (1988): 4-50.

Toop, Richard. "On Complexity." Perspectives of New Music 31, no. 1 (1993): 42-57. http://www.jstor.org/stable/833036.

Vanoeveren, Ine. "Cassandra's Dream Song." [In English]. FORUM+ 25, no. 1 (Mar 2018 2021-03-17 2018): 32-39.

Vanoeveren, Ine. Tomorrow's Music in Practice Today. University Press Antwerp, 2018.

Whittall, Arnold. "Resistance and Reflection: Richard Barrett in the 21st Century." The Musical Times 146, no. 1892 (2005): 57-70.

Xenakis, Iannis. "Theraps." edited by Editions Salabert, 1976.

Praised for her "expressive and captivating performance" (GRAMMY.com), bassist Kathryn Schulmeister brings radiant energy to her creative musical practice ranging from classical to experimental. With a fearless curiosity for collaborative environments, Kathryn's enthusiasm for seeking opportunities to integrate improvisation, movement and theatre into her creative practice have led her to thrive as an active performer in festivals and venues around the world.

Kathryn is a member of several contemporary music ensembles including the renowned Australian ELISION Ensemble, Fonema Consort (NYC), and the Echoi Ensemble (LA). She has performed as a guest artist with various adventurous international ensembles such as Klangforum Wien, Ensemble MusikFabrik, Delirium Musicum, Ensemble Dal Niente, and Ensemble Vertixe Sonora.

Equally passionate and experienced as an orchestral musician, Kathryn served as a core member of the Hawaii Symphony Orchestra for three consecutive seasons from 2014-2017 and has performed with the Ojai Festival Orchestra, Phoenix Symphony, New West Symphony, California Chamber Orchestra, Lucerne Festival Alumni Orchestra, Pacific Lyric Opera, Maui Chamber Orchestra, and Hawaii Opera Theater.

Kathryn received her Doctor of Musical Arts degree in Contemporary Music Performance from the University of California San Diego, Master of Music degree from McGill University, and Bachelor of Music degree from the New England Conservatory of Music.

For more information about Dr. Kathryn Schulmeister, please go to https://kathrynschulmeister.com/

© 2003 - 2026 International Society of Bassists. All rights reserved.

Items appearing in the OJBR may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the International Society of Bassists, and advance notification of the editors of the OJBR.

Any redistributed form of items published in the OJBR must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in The Online Journal of Bass Research in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] in [MONTH/YEAR], and it is republished here with the written permission of the International Society of Bassists.

Libraries may archive issues of OJBR in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of the OJBR and the International Society of Bassists.

Citations to articles from OJBR should include the URL as found at the beginning of the article and the paragraph number; for example:

Volume 3

Alexandre Ritter, "Franco Petracchi and the Divertimento Concertante Per Contrabbasso E Orchestra by Nino Rota: A Successful Collaboration Between Composer And Performer" Online Journal of Bass Research 3 (2012), <http://www.ojbr.com/volume-3-number-1.asp>, par. 1.2.Volume 2

Shanon P. Zusman, "A Critical Review of Studies in Italian Sacred and Instrumental Music in the 17th Century by Stephen Bonta, Burlington, VT: Ashgate Publishing Co., 2003." Online Journal of Bass Research 2 (2004), <http://www.ojbr.com/volume-2-number-1.asp>, par. 1.2.Volume 1

Michael D. Greenberg, "Perfecting the Storm: The Rise of the Double Bass in France, 1701-1815," Online Journal of Bass Research 1 (2003) <http://www.ojbr.com/volume-1-complete.asp>, par. 1.2.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.