Abstract: This paper presents a historical, analytical and editorial study on Brazilian bassist, composer and pedagogue Lino José Nunes (?- 1847) and the recently discovered manuscript of his 1838 double bass method called Methodo Prático ou Estudos Complettos para o Contrabaxo. The emergence of a thriving music scene in early 19th century Rio de Janeiro as an outcome of a war of Kings allowed the development of Nunes's career. The manuscript reveals several performance and compositional practices of the time, such as the kinds of instrument used in Brazil and their tuning, sight reading in all clefs, real time transposition, and the fistcuff fingering. It also reveals a mature composer who uses the circle of fifths, thematic development, chromaticism and procedures from Italian and German opera at local and larger levels in his double bass lessons. The performance editions of the six complete Lessons for unaccompanied double bass are discussed with the hope that they become part of the historical double bass repertory [Editor Note: The performance editions are available for download at the ISB site, for fund raising to help bass projects]. Also, the whole historical manuscript of the method (presented in Appendix II and Appendix III) is provided as an urtext reference source.

There seems to be something contradictory in the catchy title above as Brazil is not really an "old" country and the "new" double bass music presented here is not new, but the second oldest double bass music of its kind in the world, as we shall see. The history of Brazil — a notably interracial country — is recent when compared to the majority of those in Europe. As the first Portuguese arrived in the year 1500, two main musical manifestations were established: concert music of European traditions and popular music of European and African traditions. Despite the horrors of African slavery by the Europeans in the Americas, the mixing of races brought about a new social class — the mulattos — and, at the same time, their music. The Afro-Americans in the New World, compressed between the free "White" and the unvoiced "Black," largely contributed to the development of concert music outside of Europe and, even more, to the emergence of popular genres such as the ragtime in North America, the habanera in Central America, and the lundu and modinha in South America (Cançado, 2000, p.5-7). But what are the reasons that led Brazil to occupy the center stage for the earliest relevant concert music scores in general to be found in the New World? First, the intense gold rush at the beginning of the 18th century made it possible for every major town to have small chamber groups and orchestras1 and produce their own music. Second, the unique and surprising translocation of a European empire to Brazil in the beginning of the 19th century brought with it an outstanding musical environment never experienced before in the Americas.

In 1808, trapped on the Iberian Peninsula between the Atlantic Ocean and the military expansionist forces of Napoleon Bonaparte, King John VI of Portugal had no choice but to flee to colonial Brazil in forty-six ships with a select population of about 12,000 courtesans (Bueno, 2004, p.142). Planning a trip with no return, the king created in Brazil a cultural scene that the Portuguese were accustomed to in Europe. In very little time, the Royal Chapel Choir and Orchestra were established in Rio de Janeiro " . . . with a quality equivalent to important European towns . . . " (Lino CARDOSO, 2006, p.337). Besides sacred, symphonic, and operatic music, military music was very present as an evident sign of the newly created empire (Binder, 2006, p.25; Tinhorão, 1976). But before that, the musical life in Rio was already in progress, both popular and classical, a scene in which the music school of the mulatto Father José Maurício Nunes Garcia, one of the most distinguished musicians in colonial and imperial Brazil, became a reference for the poor to study for free (Mattos, 1967, pp.31-32). There is the starting point for our personage: Lino José2 Nunes (? - September, 5, 1847).3

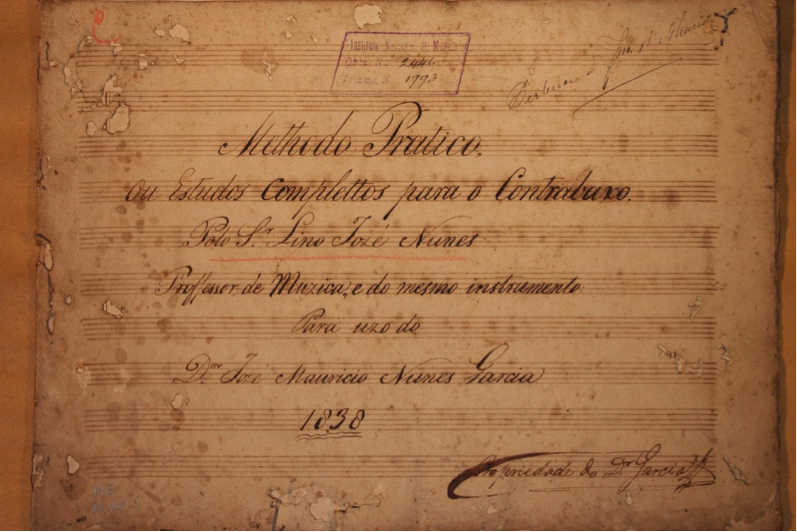

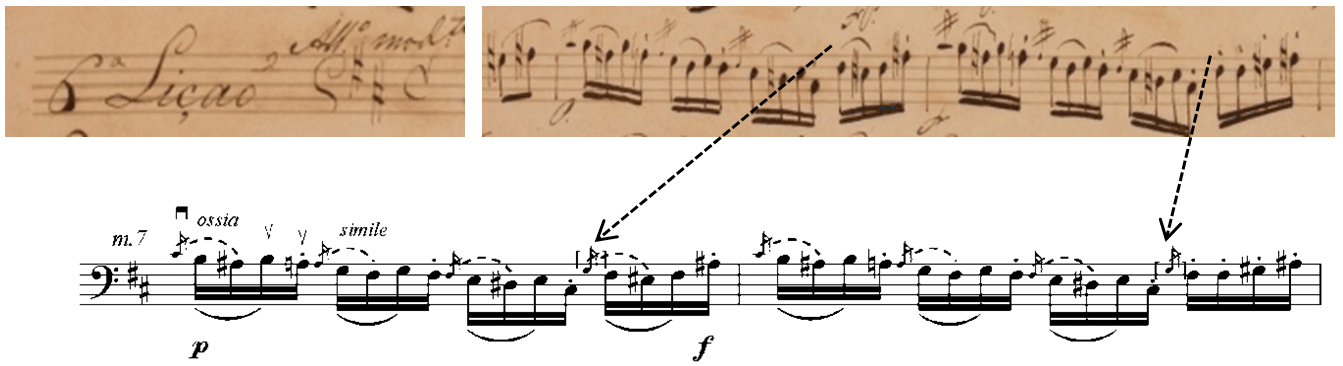

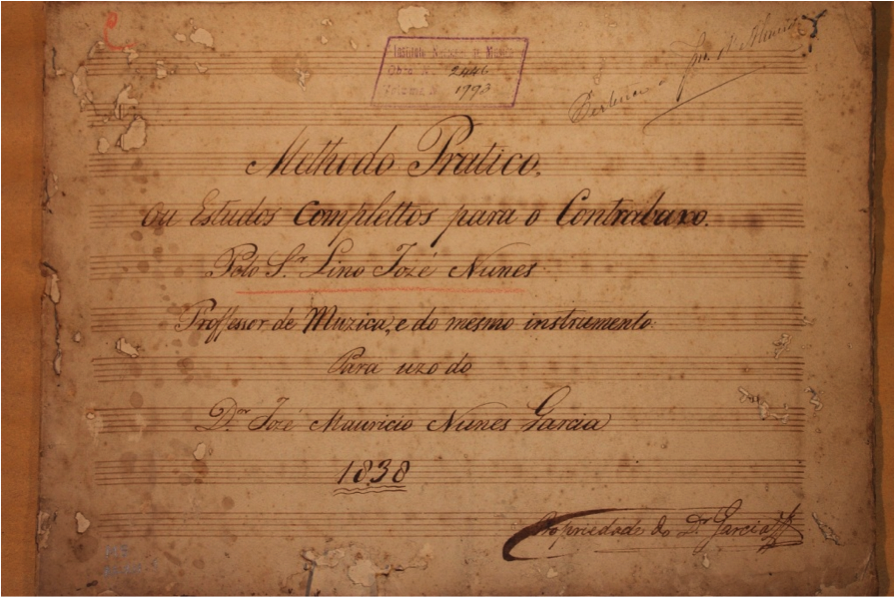

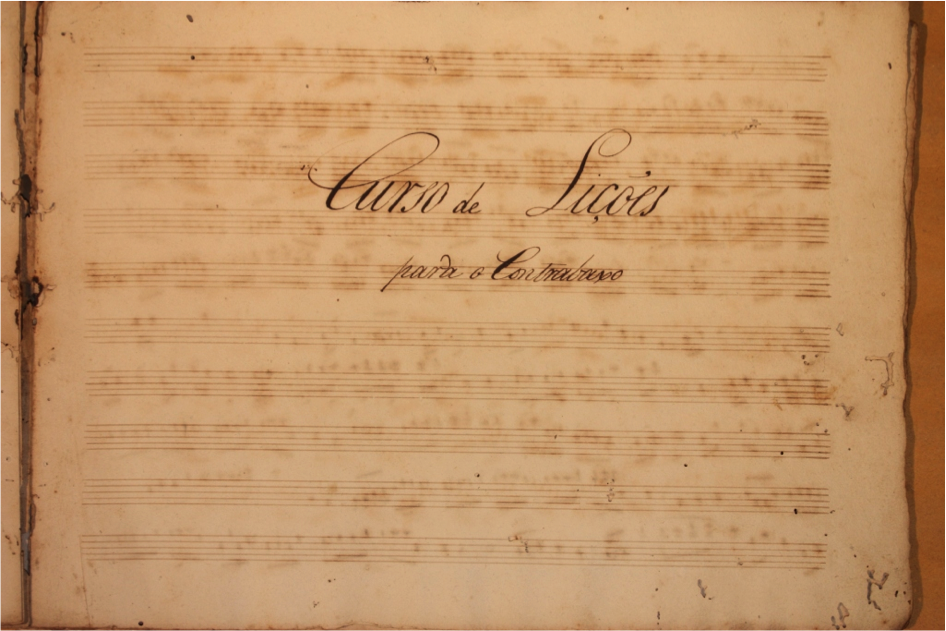

Father Garcia took the young Nunes as a protégé who, in return, would show gratitude during his whole career. Born to Paula Joaquina (no middle or last names, which was typical for slaves) and to an unknown father (possibly the common case of "bastard" offspring of white men with female slaves),4 Nunes showed his affectionate relationship to the Garcia family in two documented occasions. First, the mature Nunes commissioned Father Garcia for the Santa Cecilia Mass (Mattos, 1967, p.34), considered one of his masterworks. Second, he dedicated to Dr. Garcia Jr. his "Methodo Prático ou Estudos Complettos para o Contrabaxo" ("Practical Method or Complete Studies for the Double Bass"), from now on called only "Methodo"(Nunes, 1838). Dr. Garcia Jr. was one of Father Garcia's children, who probably studied double bass with Nunes, as can be seen on the front page of the manuscript5 in Ex.1. Unfortunately for the history of the double bass, he gave up music for medicine.6

Ex.1 - Front page of Lino José Nunes's 1838 "Methodo Pratico ou Estudos Complettos para o Contrabaixo", dedicated to Dr. José Maurício Nunes Garcia.

Nunes excelled as a distinguished musician, becoming a singer, multi-instrumentalist (double bass, guitar, and Portuguese guitar), teacher, and composer, who sometimes acted as a conductor. As a composer he also left "Cupido tirando [a aljava] dos hombros" ("Cupid taking off [the quiver] from his shoulders"), "Se os meus suspiros podessem" ("If my whispers could"), and "De Huma simples amizade" ("Of a simple friendship"), three pieces for voice and piano. These modinhas were published in 19th century Portugal in a collection of Brazilian and Portuguese modinhas and re-published by Doderer (Org., 1984, pp.60-71, pp.102-103 and pp.114-115, respectively). [Editor Note: The arrangements of these three pieces for double bass, voice, and piano are available for fund raising download at the ISB site to help bass projects.] As a young man, he sang at the Royal Chapel Choir and later became the principal double bassist of the Royal Orchestra, his main job in life. Nunes also played in several other ensembles in Rio, such as those of the Royal Chamber, the Teatro São Pedro de Alcântara Theatre, and the Teatro Tivoly. He taught at the Conservatório Dramático Brasileiro, at the Dance and Music Conservatory of Rio de Janeiro, and at the private school of Father Garcia, where he studied as a young man (André Cardoso, 2011, 427-429). Being the foremost double bassist in the first half of 19th-century Brazil, Nunes probably played in most of the many operas premiered or re-staged during his time at the Royal Orchestra: 37 by Rossini, 15 by Donizetti, 6 by Bellini, and one by Verdi (Andrade, 1967, vol.1, pp.113-126; vol.2, pp.121-130). He was probably the bassist chosen for two premières of Mozart's masterworks in Brazil: the Requiem conducted by Father José Maurício in 1819 in the famous arrangement by Sigismund Neukomm7 (Mattos, 1967, p.29) and the opera Don Giovanni in 1821 (Mattos, 1967, p.33). Finally, the importance of Nunes in Rio's concert music scene is illustrated by the outcome of the major political-economic crisis during the reign of King Pedro I, who composed and played several instruments: harpsichord, violin, flute, clarinet, bassoon, and trombone (Bueno, 2004, p.170). Drowned in debt, the country's political master minds saw no other outlet other than sending the bohemian king back to Portugal (Andrade, 1967, vol.1, p.163, p.169, vol.2, p.231)8 and dramatically cut financial costs everywhere. In an 1828 desperate letter, thirty-seven musicians of the Royal Chapel Orchestra, including Nunes, wailed and begged to keep their jobs:

" . . . having to bear so far with great suffering and silence all those misfortunes that the inevitable series of unfavorable and more or less mortifying happenings have fallen over their heads . . . the excessive evils that afflict them. Dedicated since their childhood to a not so happy a profession . . . They used a good deal of their years in a defenseless study . . . fruit of their labor . . . a decent subsistence, an award to which every non-idling citizen should aspire. There was a time when they appropriately received it . . . [but now] a bitter existence, with some having to look for the sustenance of their numerous and indispensable families; not being able to have another employment that would help to alleviate their hardship: which means will they choose in order to escape so violent and oppressive a state? . . . " (quoted by Andrade, 1967, vol.1, pp.161-162; underlines by the present author).

But it was to no avail. The Royal Chapel Orchestra was closed by decree in 1831. However, among some seventy instrumentalists (Lino Cardoso, 2006, p.5), Nunes was one of only four kept — paid by service9 — in order to provide the minimum support to the essential activities of the choir (also dramatically reduced by a government decree; Andrade, 1967, vol.1, p.164). Striving to survive as a musician in a scenario drastically changed, Nunes offered his services to teach, compose, and perform in both popular and classical circles. In a newspaper advertisement published in Rio he had the guts, in a very sexist society,10 to announce that he would " . . . teach all people of both sexes . . . all kinds of music . . . ,"especially the fashionable " . . . Italian canzone and Portuguese modinhas . . . everything with accompaniment of "viola" [the Portuguese guitar]" (newspaper clip with unmentioned name and date; Andrade, 1967, vol.2, p.209).

How can we place Nunes's "Methodo" in the context of double bass history? French organist and composer Michel Corrète (1707-1795) was the author of at least seventeen tutors for musical instruments (Sas, 1999, p.100). Among them is a collective method with an extensive title — "Méthodes pour aprendre à jouer de la contrebasse à 3, à 4 et a à 5 cordes, de la Quinte ou Alto et de la Viole d'Orpgée . . . " — published in Paris in 1773 (Miller Lardin, 2006; Corrète, 1977 [reprint]), which includes the violone with three, four and five strings, besides two other instruments: the alto viol and the viola d'Ophée. During the sixty-five years that separate Corrète's and Nunes's methods, only nine others were written (see list in Appendix I for a list of historical double bass methods) and only two by double bass players. The first consisted of volumes 1 and 2 of "Méthode complète de contrebasse a 4 cordes" (Hause, Paris, c.1828) by Bohemian Wenzel Hause (1764-1845), whose school was established in Prague and then, extended to Vienna and Leipzig (Hartmann, 1983, p.11-12). Hause's method would be complete only in 1840, when volume 3 was published in Prague. Second, Spanish bassist José Venancio López (?-1852), who taught at the Madrid Conservatory, wrote his "Método de Contrabajo" but it is still lost (Gándara, 2000). Thus, Lino José Nunes's "Methodo" can be considered as the second double bass method written by a bassist. Moreover, besides revealing performance practices of that time in detail, Nunes's "Methodo" brings a musical content that is much more attractive when compared to his predecessor Hause's, and even to the very popular method of Hause's most famous pupil Franz Simandl. Simandl's is similar to his master's and considered by pedagogues as being didactically problematic and having an arid musical content (Karr, 1995, p.54-57; Sankey, 1978, p.70-71; Montgomery, 2011, p.5-6).

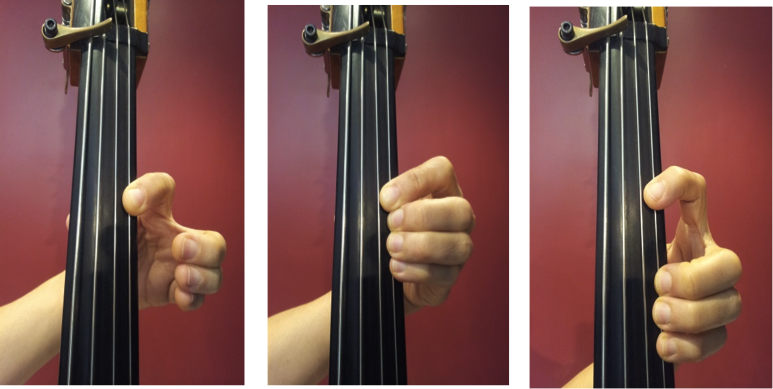

The physical difficulties associated with playing the double bass can be appreciated in Italian bass pedagogue Isaia Billè's own 1890 poem, published as an epigraph of his seminal book, Nuovo metodo per contrabasso a 4 e 5 cordes. He mentions " . . . thy thick and hard strings . . . " (" . . . tue grosse e dure corde . . . ") that ineptly played, resulted in " . . . grotesque voices and so deaf notes . . . " (" . . . grottesche voci e note tanto sorde . . . ") (Billè, 1922, p.117). Raymond Elgar (1987, p.74), in the first book of his trilogy dedicated to the double bass, Introduction to the double bass, reports that one of the gut strings of the Paris Conservatory's octobass has a diameter of half an inch (1,27 cm)! Elgar (1987, p.105) also talks about historical double bass methods and mentions the "fistcuff"(or "fisticuff") fingering, the firm and tight grip of the left hand on the double bass neck that the bassist resorted to when dealing with the difficulty of pressing down the strings.11 As the name suggests, the "fistcuff" has only two options: the open position (played with finger 1) or the closed position (played with finger 4 to which fingers 2 and 3 were added). The closed position was used for both half step (indicated by the lower case "m" indicating a "minor" second) and whole step departing from finger 1 (indicated by the capital "M" indicating a "major" second) to play, for example, the notes A3, A#3, (or Bb3) and B312 as shown in Ex.2.

Ex.2 — The "fistcuff" fingering: notes A3 with finger 1, A#3 with finger 4 ("minor" position) and B3 with finger 4 ("major" position) based in Elgar's description in Introduction to the double bass (1987, p.105).

In vol.4 of his 7-volume method, Marangoni (1929, p.42) mentions the "Babylon" of fingerings for the double bass: " . . . after almost 300 years of its first presence in the orchestra, there is not a single fingering system, as it happens with the other instruments of its family". He presents a synoptic table of what seems to be the most influential double bass schools in Italy. There we can infer that a common limitation in double bass construction at that time was the excessive string tension near the nut, as fistcuffs were common in Europe. He also brings the surprising information that this technique was used by various double bass icons of the double basses tuned in perfect 4ths: Dragonetti (when playing B2-C3 on the A-string or E3-F3 on the D-string), Bottesini (when playing B2-C3 on the A-string, E3-F3 on the D-string or B3-C4 on the G-string) and even Simandl (when playing F#2-G2 on the E-string) In his method, J. Fröhlich (1829) gives the "fistcuff" fingering a different name — "clamp" — from which we can also infer the dual-only use of the left hand fingers. However, he advocates the substitution of finger 4 by finger 3 in higher positions, where the strings are more flexible. The practice of "fistcuff" was in use in Brazil in the 19th century and is documented in Nunes's "Methodo".

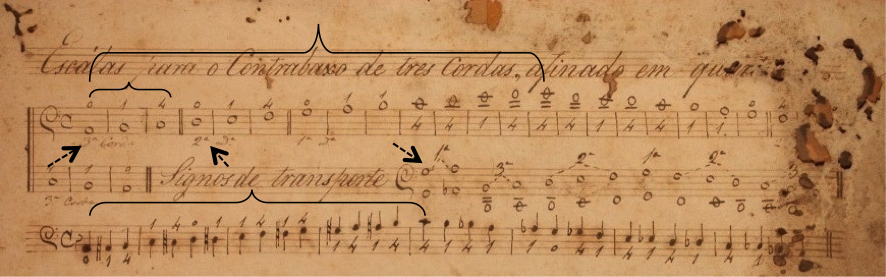

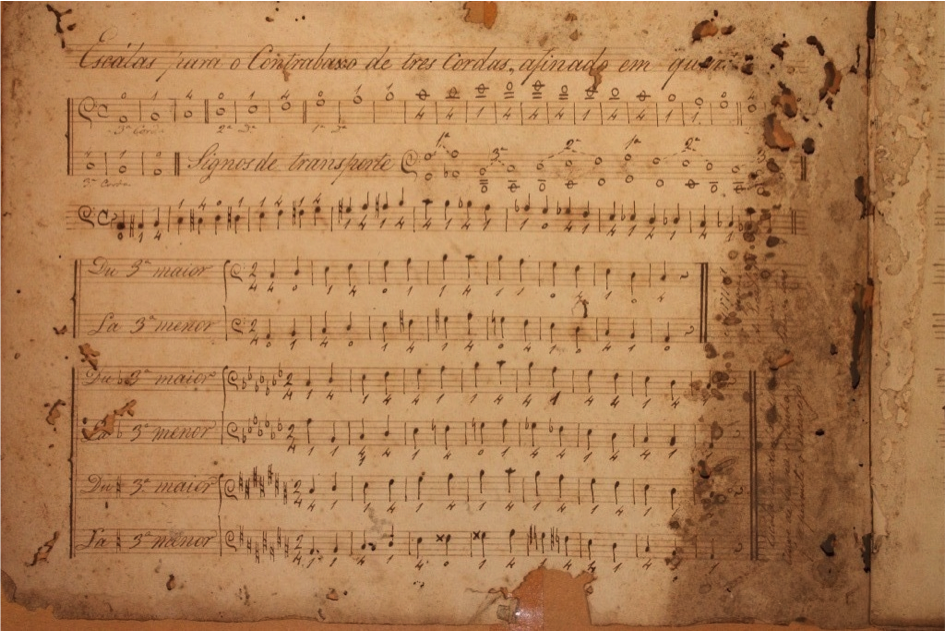

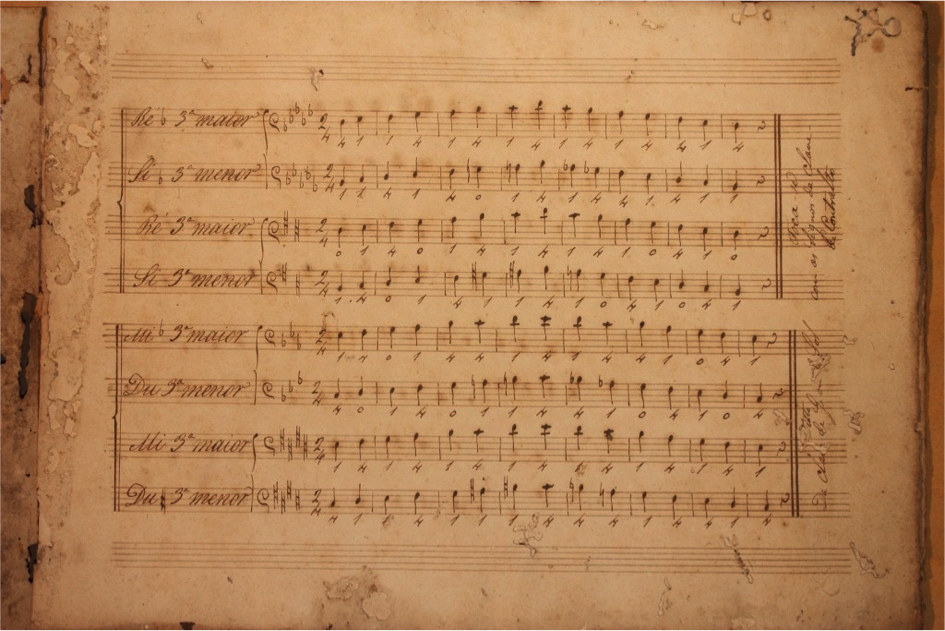

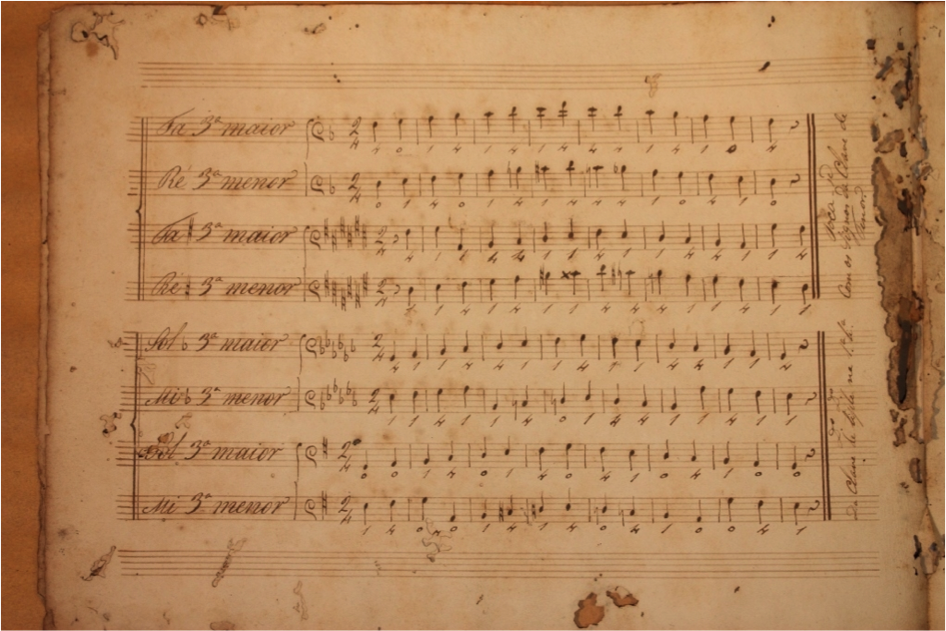

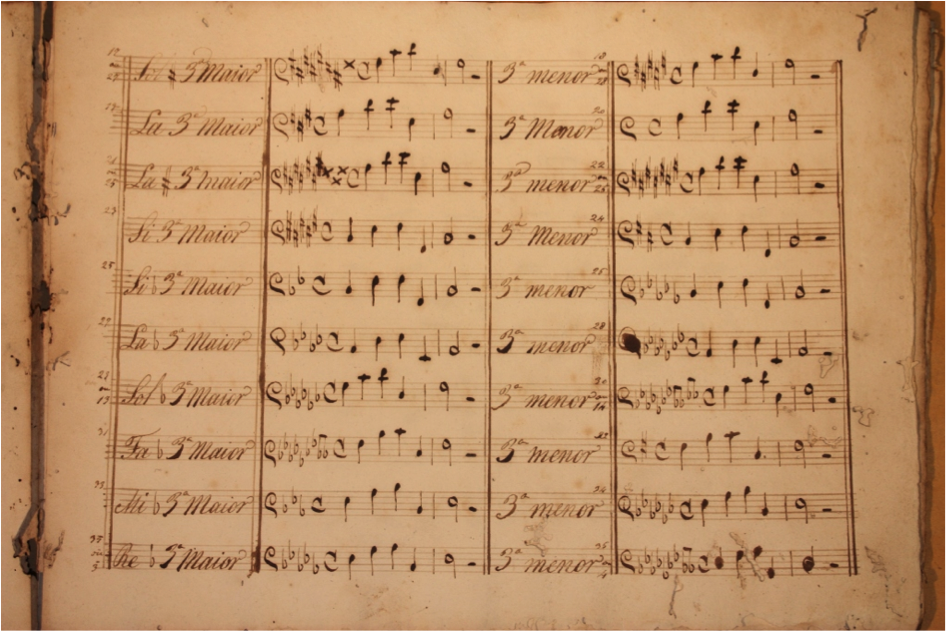

Lino José Nunes's "Methodo"is divided in two larger parts. Part I, devoted to the double bassist's preparatory daily practice, is subdivided into three smaller sections. Section A (Nunes, 1838, pp.2-5, Ex.3), named as "Escalas para o contrabaxo de tres cordas afinado em quartas" ("Scales for the 3-stringed double bass tuned in fourths"). Before the scales, Nunes provides three preparatory elements. The first element is a scalar diatonic A minor scale, from A2 to G4, covering the whole orchestral tessitura of the 3-stringed bass explored in his "Method". In this scale, while the symbols "o", "1" and "4" over the notes reveal the "fistcuff" fingering system, the word "3ª corda" ("3rd string") under the first notes indicates the string for the notes to be played on. The highest note in the "Method ," a G4, suggests orchestral bassists in Brazil did not know the capo tasto technique and possibly employed the practice of leaving gaps in the bass line (or transposing it one octave down) when facing notes such the G#4 and A4, very common for the cello's 1st string.13 On the other hand, the lowest note, A2, confirms the most common double bass used in Brazil, the 3-stringed double bass tuned in 4ths. Secondly, Nunes presents the "Signos de transporte" (Transposing signs), constituted by whole-note pairs to illustrate, at the same time, the reading notes and the corresponding actual notes. Thirdly, Nunes introduces a chromatic scale in quarter notes from A2 to C3, where symbols for the index and "pinky" fingers suggest again the "fistcuff" fingering and, probably, the only one known (or at least documented) in Brazil.

Ex.3 - Range of the "Brazilian" double bass (A2 to G4), the "fistcuff" fingering system, string designation, the octave transposition and the chromatic scale (Nunes's Methodo, Part I, Section A, p.2).

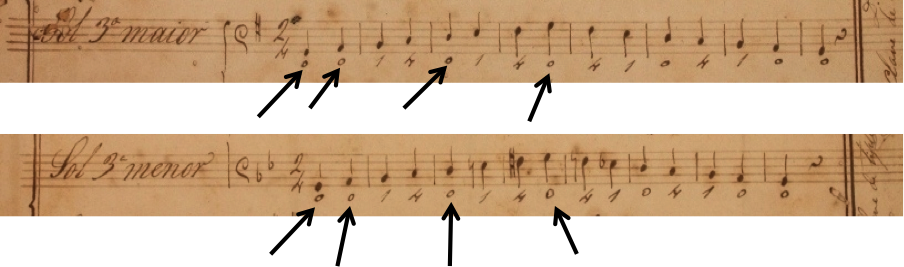

But there is a discrete piece of information in the "Methodo" that suggests another type of double bass in use in Brazil in the first half of the 19th century. When Nunes provides the G major (p.4) and G minor (p.5) scales with their respective fingerings, he places the symbol "o" (the small circle symbol that represents open strings) above the notes G2, A2, D3 and G3 (Ex.4), which points to the 4-stringed double bass with its 4th string tuned just a major second below the 3rd string. The reason behind it is probably the difficulty to manufacture strings to go that deep. This tuning is mentioned by Brun (1982, p.181) in Nicolai's 1816 bass method, by Planyavsky (1998, p.121), and much earlier in a treatise by Thomas Baltazar Janowka in 1715. The possibility for a 3-stringed double bass tuned G2 - D3 - G3 "à l'italienne", according to Brun (1982, p.168) seems improbable due to the four open string symbols in Nunes's manuscript. But those are the only instances Nunes mentions the low G2, which points to the existence of 4-stringed basses in Brazil, in spite of the apparently massive predominance of 3-stringed instruments.

Ex.4 — Open string symbols ("o") in the G major (p.4) and G minor (p.5) scales suggest the use of the 4-stringed double bass tuned to G2-A2-D3-G3 in Imperial Brazil (Nunes's Methodo, Part I, Section A, pp.4-5).

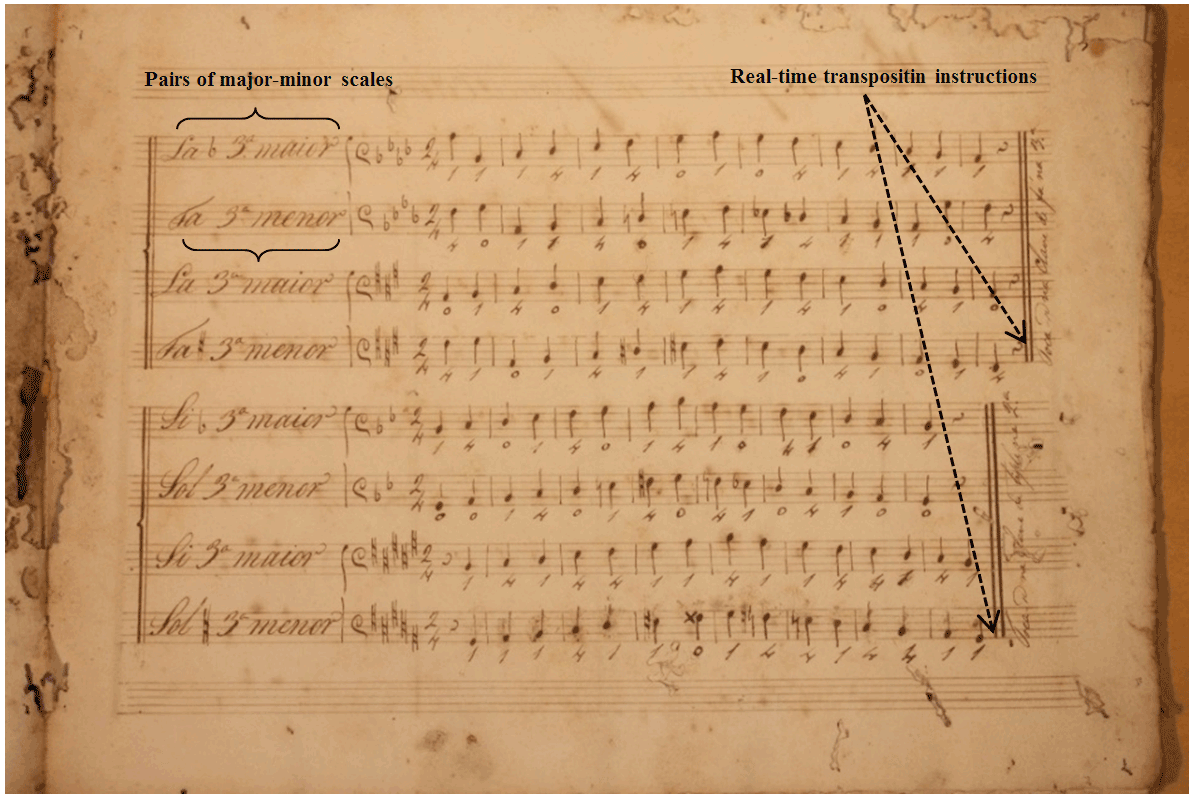

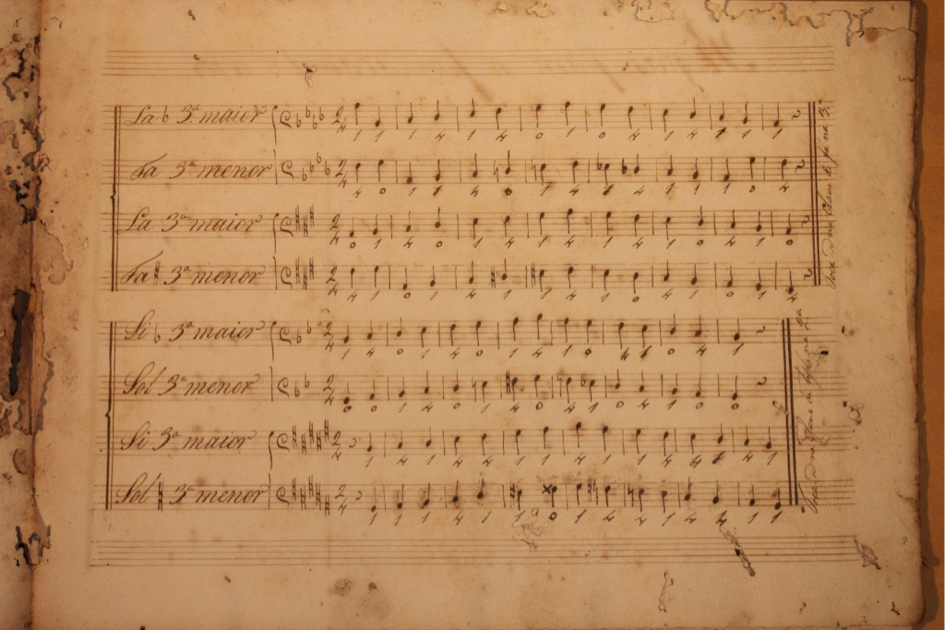

Nunes provides pairs of one-octave scales in major keys (C major - C flat major etc.) followed by their relative minor keys (A minor - A flat minor etc.). For each group of four scales, there are instructions written vertically for the practice of transposition in various ways. For example, on p.3 (Ex.5), at the end of the top system is written "Toca-se na clave de Fá na 3ª [linha]" ("To be played in the bass clef in the 3rd [line]"), while at the end of the bottom system is written "Toca-se na clave de tiple na 2ª [linha]" ("To be played in the "tiple" [the choir´s sopranino boy] clef in the 2nd [line]"). These indications suggest that the skill to transpose in real time (i.e., during the performance) was in demand in Imperial Rio, a city known to receive famous Italian opera divas and castrati.

Ex.5 — Major and minor scales in all tonalities followed by instructions for real time transposition in various clefs (Nunes's Methodo,Part I, Section A, p.2).

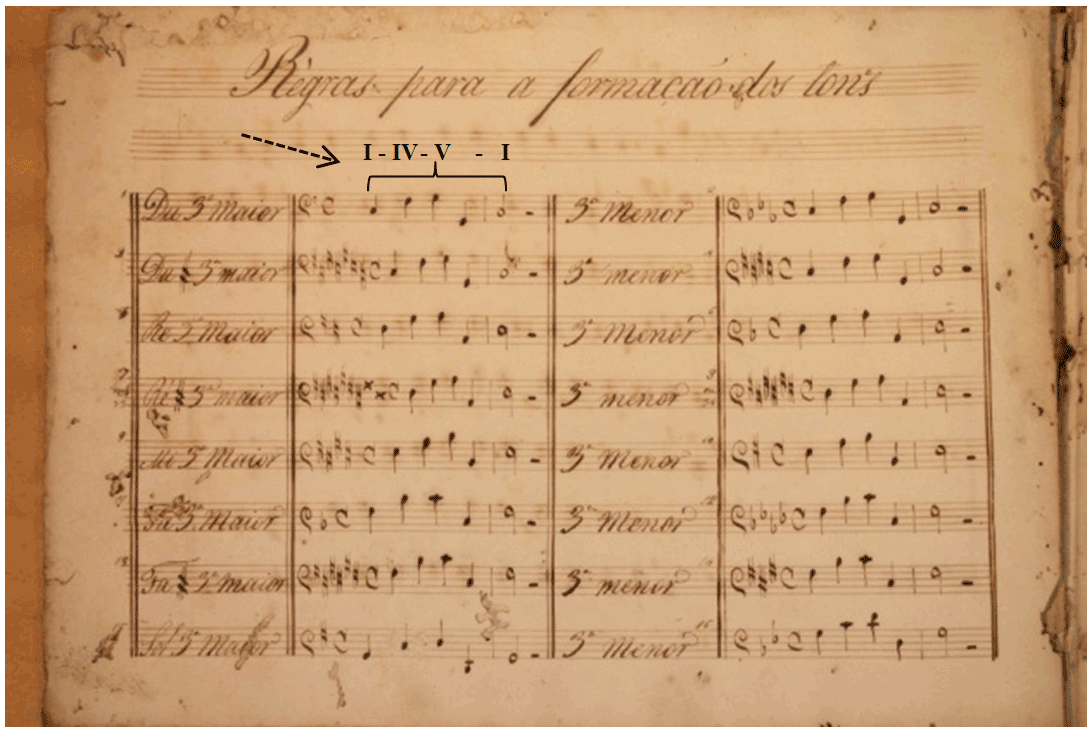

Section B of Part I in the "Methodo" (Nunes, 1838, pp.6-7, Ex.6) is called "Règras para a formação dos tons" ("Rules for the establishment of tonalities"; pp.6-7) and presents cadential formulas, which bassists should learn in order to realize the I-IV-V-I harmonic progression in all major and respective minor homonymous keys. Pedagogically, these formulas seem to be connected with the performance practice of accompanying singers who need to change the key of the music, such as in an operatic solo.

Ex.6 — Cadential formulas for the orchestral bassist to be able to accompany in all keys (Nunes's Methodo, Part I, Section B, p.6).

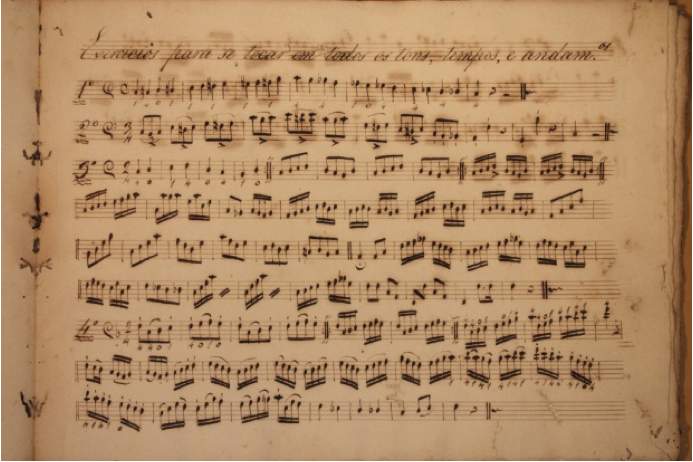

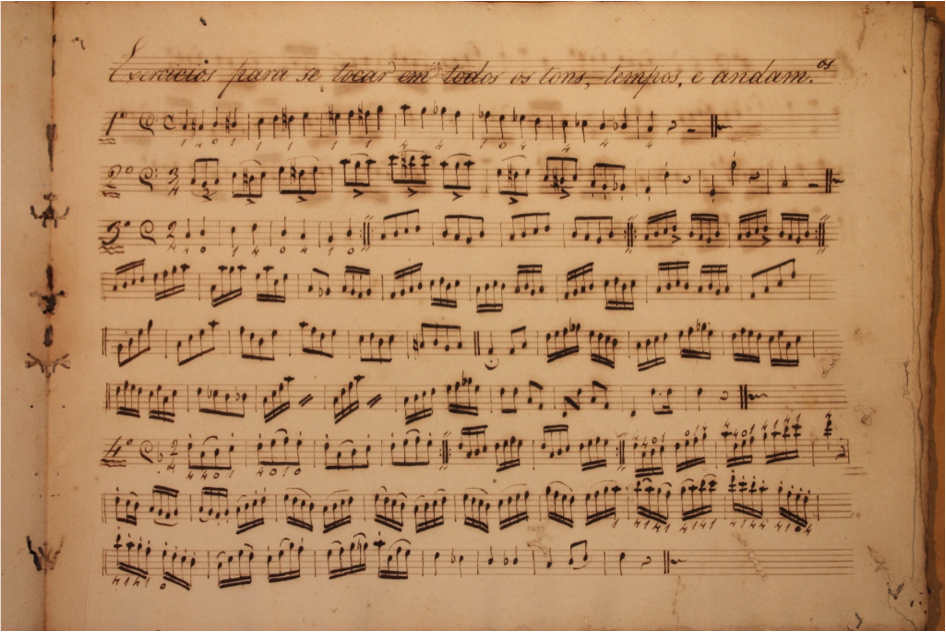

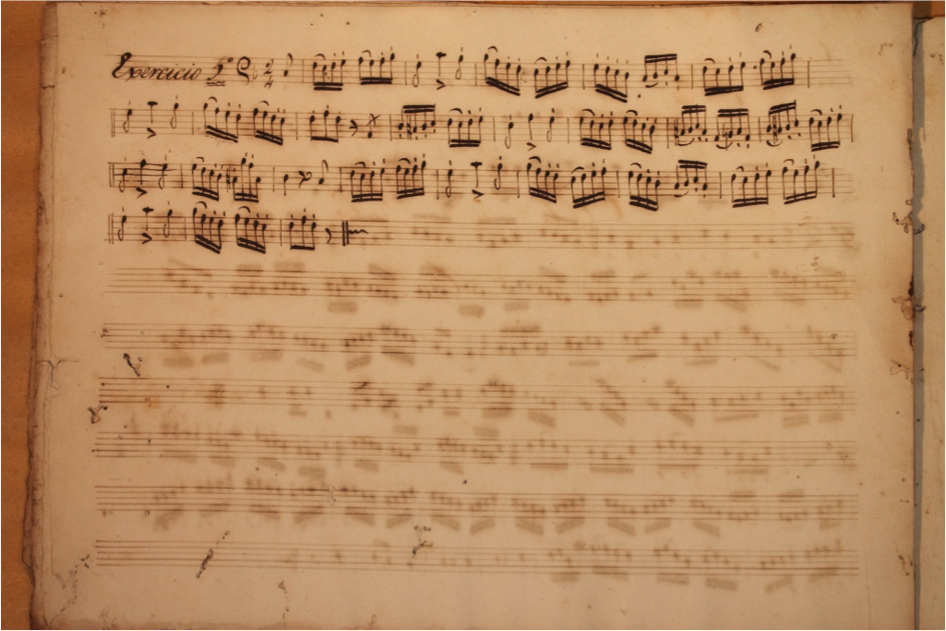

As its name suggests, Section C of Part I in the "Methodo" (Nunes, 1838, pp.8-9, Ex.7), "Exercicios para se tocar em todos os tons, tempos e andam." ("Exercises to be played in all tonalities, tempi and character"; pp.8-9) aims at providing the double bassist with the flexibility required in the most common operatic and symphonic repertory: duple, triple and quadruple meter, chromaticism, ornaments, scales and arpeggios, syncopations with off-beat accents, diverse articulation (2, 3 and 4-note slurs, staccato, marcato), etc.

Ex.7 — Exercises in all keys, tempi and character for the flexibility of the double bassist (Nunes's Methodo, Part I, Section C, p.8.).

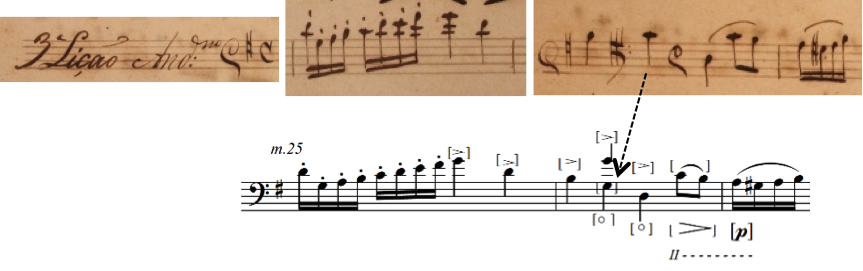

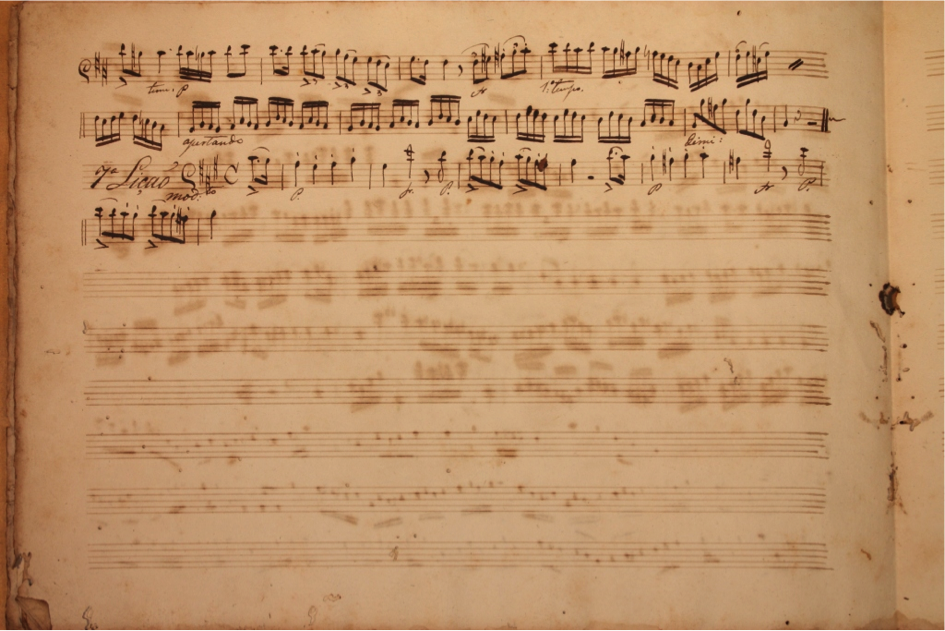

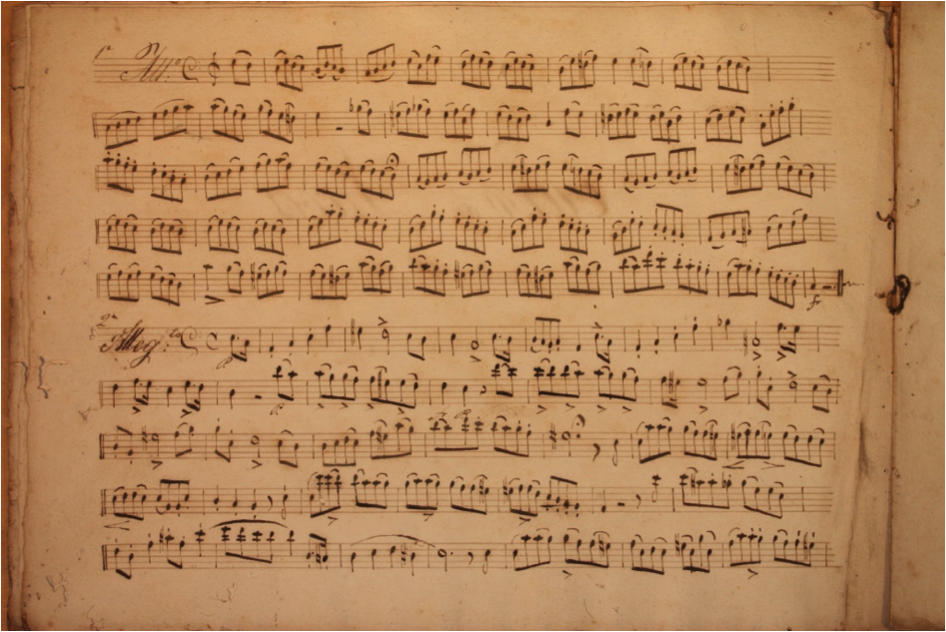

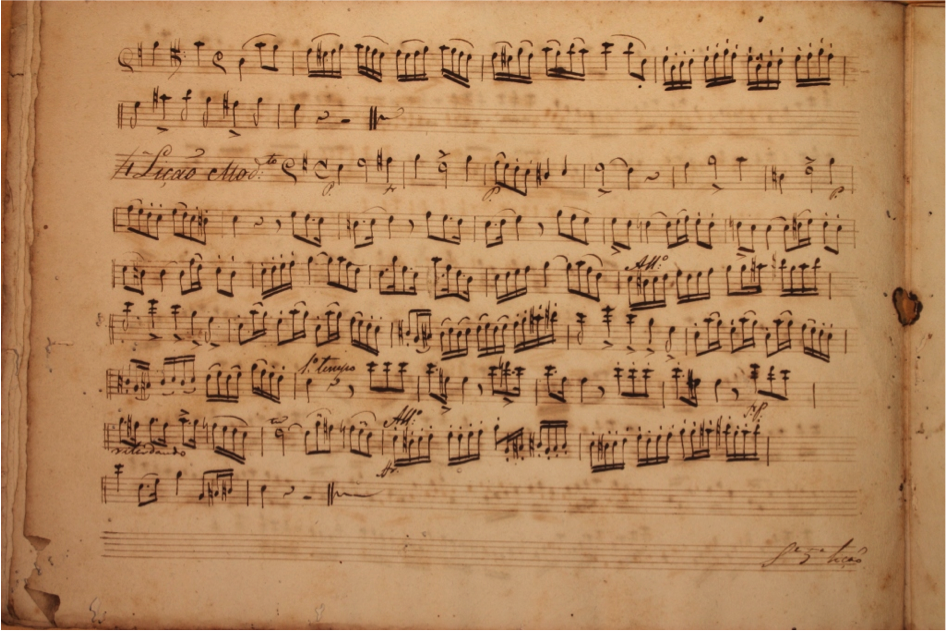

Part II of the "Methodo", called "Curso de Lições para o Contrabaxo" ("Course of Double Bass Lessons"; pp.10-15), was left incomplete in m.8 of the 7th lesson. However, this section brings the most musically interesting material of the "Method", namely the six complete lessons, which can be performed in recital programs as a set or separately. As J. S. Bach excelled in his Well-Tempered Clavier (1722), Nunes's plan was to pedagogically provide a set of 24 double bass lessons, covering all major and minor keys. His unifying scheme around the circle of fifths is evident in these six complete lessons, arranged in pairs of major-minor tonalities: C major-A minor, G major-E minor, D major-B minor. Other unifying factors among these lessons are the recurrence and development of thematic materials, such as military rhythms (reflecting the establishment of the new Brazilian Empire), syncopations, and opera elements (fermatas, recitatives, ornamented lines, the aria-cabaletta pair), as it will be shown. On the other hand, Nunes gives each lesson a unique personality, allowing the bassist to focus on specific technical elements.

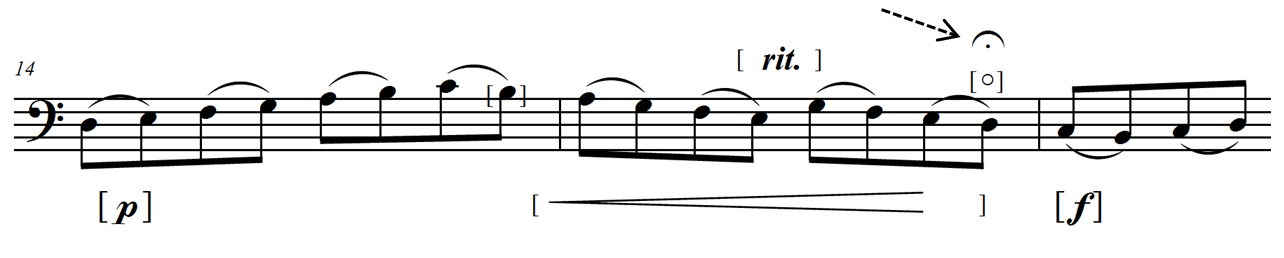

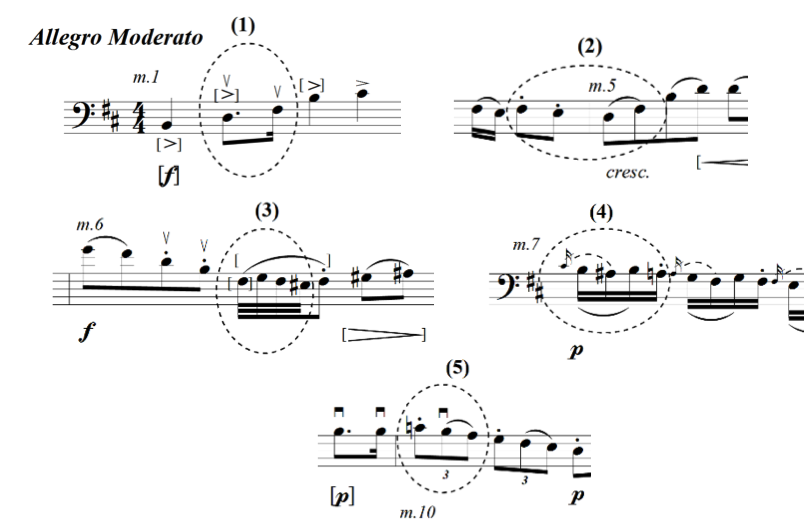

Lesson 1, constructed as an A-B-A'-C form, acts as an introductory piece, constructed with easier and technically more restricted materials, namely the key of C major with no modulations (only a few altered neighboring tones), the limited range of a minor 10th (from A3 to C4), and mostly stepwise 8th notes with two-by-two slurs or staccato. But Nunes was also pedagogically concerned with the accompanying role of the orchestral double bass, especially in opera, a most favored genre in Imperial Rio. In the last note of m.15 he places a typical opera fermata, so the bassist can practice that neuralgic moment when he/she must pay more attention to the conductor, who pays attention to the soloist singer during his/her suspension of the metrics (usually happening in a fermata, cadenza or recitative) to finally resolve on the downbeat of the next measure (Ex.8). All notated symbols and words between brackets in the musical examples and in the performance editions reflect interferences to the original manuscript.

Ex.8 — Fermata in Nunes´s Lesson 1: opportunity for the double bassist to practice a crucial element of the opera, a most favored genre in Imperial Brazil.

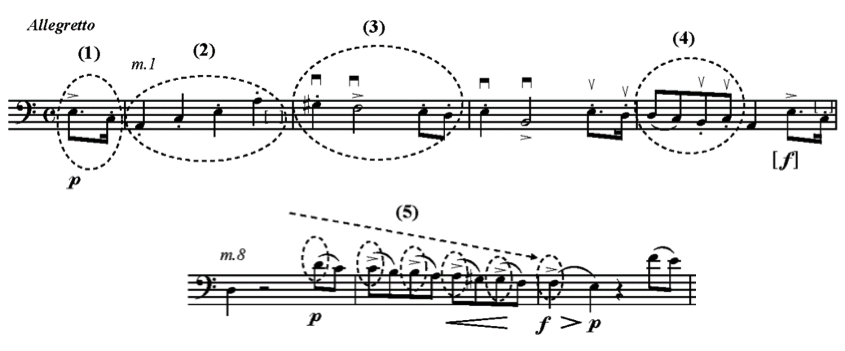

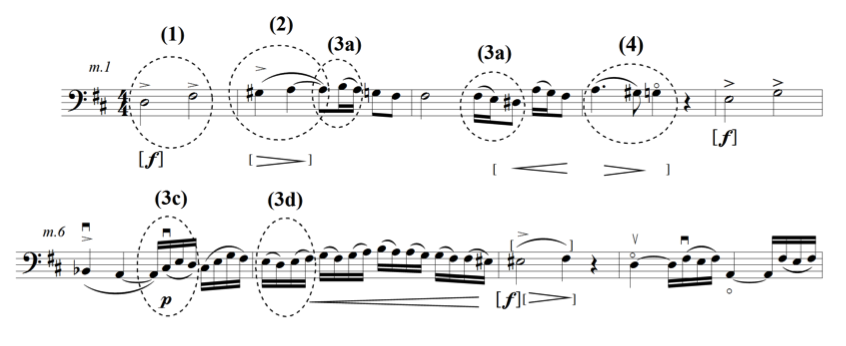

In Lesson 2, Nunes explores the contrast between military inspired music and the opera cantabile, very common genres in Imperial Rio in the first half of the 19th century. Although it does not modulate, Lesson 2 is musically much more challenging than Lesson 1. In the key of A minor, its rhapsodic A-B-C form is based on the thematic development of five motifs (Ex.9): (1) the martial pick up, (2) the marching staccato quarter notes, (3) the martial syncopation, (4) slurred and staccato 8th-note groups, and (5) the cantabile descending line of two-by-two slurred 8th notes in the fashion of the so-called Mannheim sighs (Sadie, 1988, p.462).

Ex.9 — The five thematic motifs in Nunes's Lesson 2.

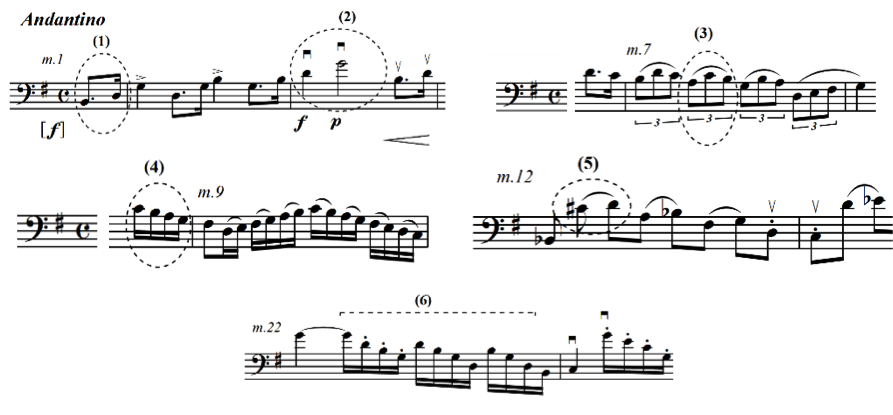

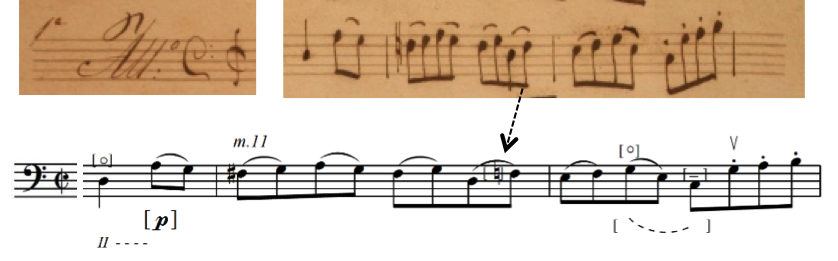

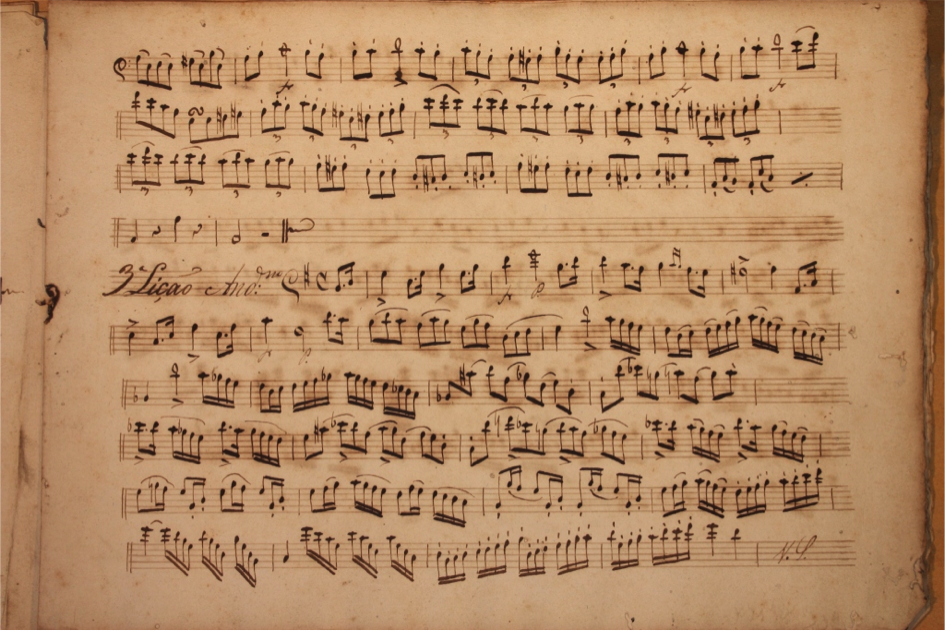

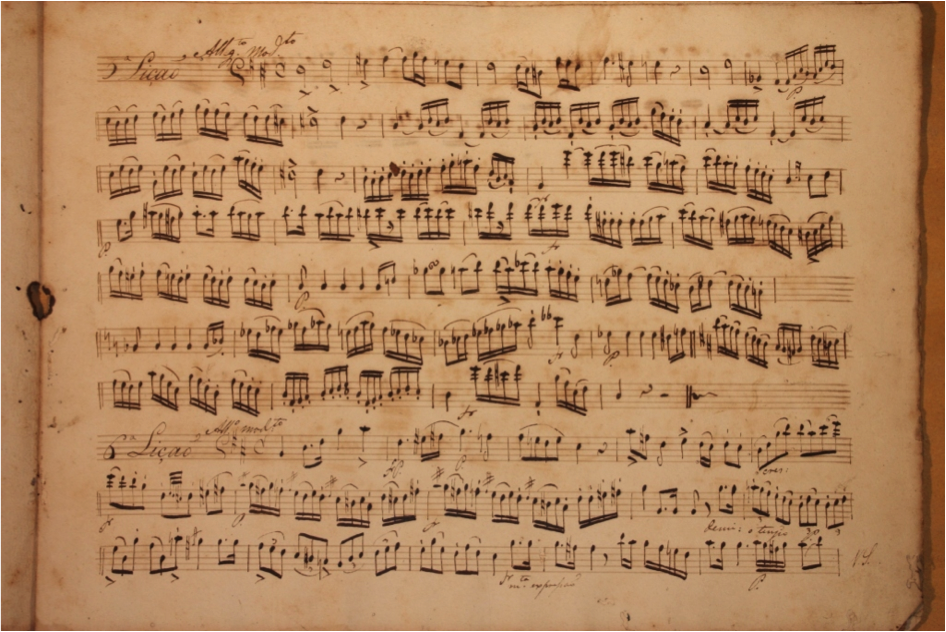

Lesson 3 begins in G major, modulates to G minor in m.10 and returns to the home key in m.18. Not just this procedure, but also the use of secondary dominants and non-functional chromaticism gives the bassist the opportunity to focus on intonation correction of altered notes such as B flat, E flat, F natural, C sharp and A sharp. Heavily based on the classical patterns of double period phrasing (m.1, 8, 12, 18, 22), melodic repetitions and sequences, the rhapsodic nature of Lesson 3 (an A-B-C-D-F-G structure) seems to be derived from the theme and variations form, departing from six motifs (Ex.10): (1) the martial pickup, (2) the martial syncopation, (3) sequenced triplets (4) 16th-note groups, (5) syncopated slurred 8ths, and (6) virtuosic 16th-note arpeggios, reflecting Nunes's pedagogical preoccupation to teach skills in demand for the symphonic and operatic repertory.

Ex.10 — The six thematic motifs in Nunes's Lesson 3.

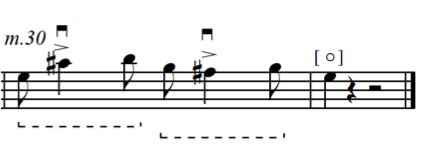

At the end of Lesson 3 (m.30), possibly pointing to his African descent, Nunes uses another kind of syncopation, namely the emerging so-called Brazilian syncopation (Ex.11). Typically in faster rhythms and sequenced, the Brazilian syncopation began to appear in nineteenth-century popular genres such as the lundu and modinha (Lima, 2010, Lima 2005) and become a standard feature in the twentieth-century genres of choro, samba, and bossa nova.

Ex.11 — The so-called Brazilian syncopation, used by Nunes at the end of Lesson 3.

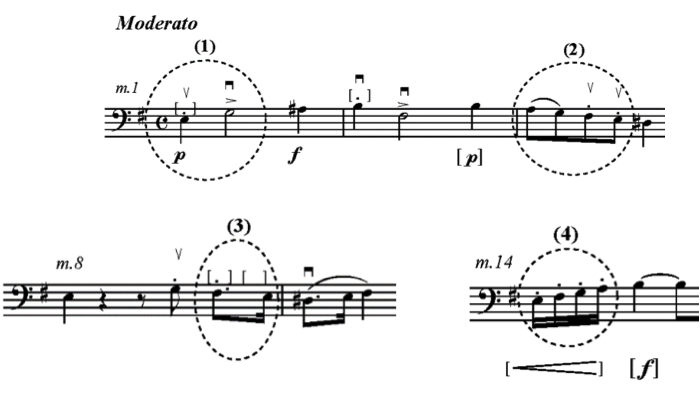

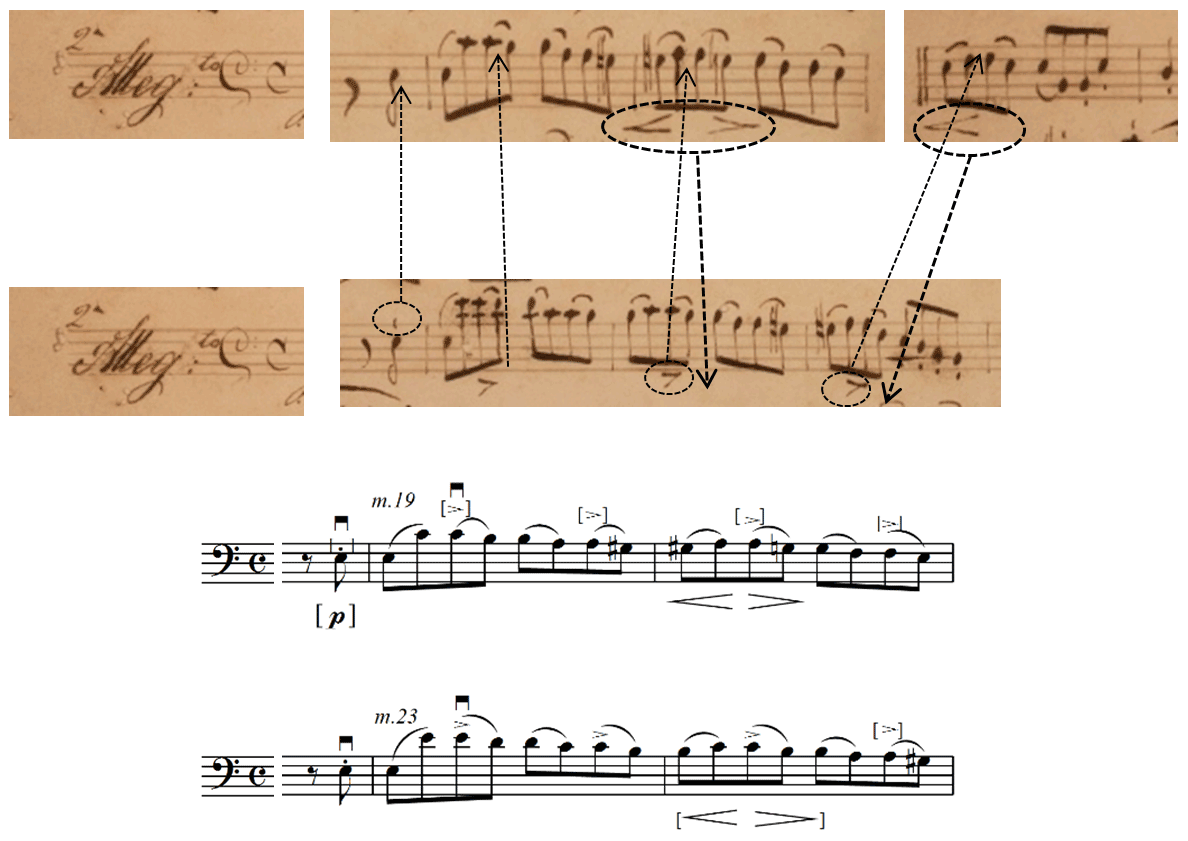

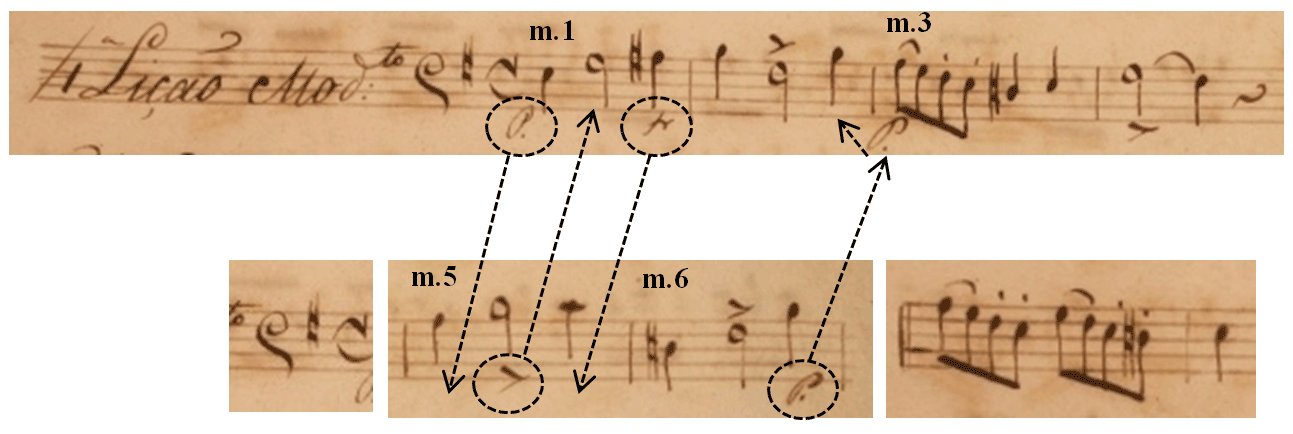

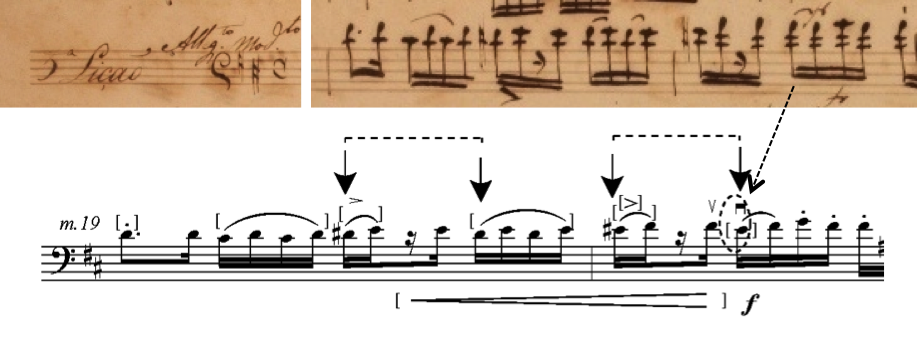

An Italian opera expert (Andrade, 1967, vol.1, pp.113-126; vol.2, pp.121-130), Nunes favors that dramatic genre in Lesson 4. The two pairs of contrasting tempi (Moderato-Allegro in mm.1-23 and 1° Tempo-Allegro in mm.24-33), makes an A-B-A'-B' form and were clearly inspired by the aria-caballeta sequence. Here, they are like two miniatures of this typical Rossinian operatic pair (Taruskin, 2010b, p.1 of 9), which were very familiar to Nunes. Almost all materials in Lesson 4 are derived from four motifs (Ex.12) that had already appeared in previous lessons: (1) the large syncopation in m.1, (2) the four 8th-note group with two slurred notes followed by two staccato ones in m.2, (3) the martial dotted 8th note followed by a 16th note in m.8, and (4) scalar groups of 16th notes in m.14.

Ex.12 — The four basic motifs of Lesson 4.

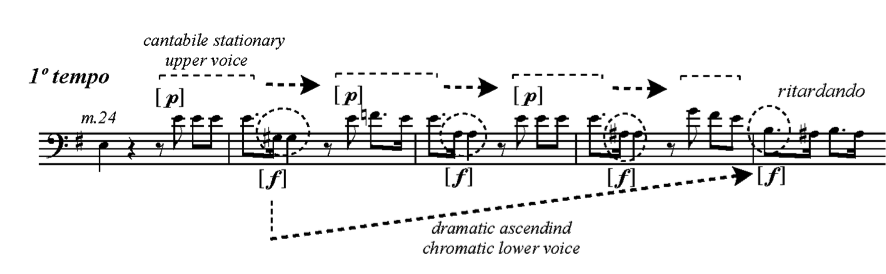

Although Lesson 4stays in the key of E minor all the time, Nunes provides variety by giving bassists another opera treat. In section A', he creates a recitative with a polyphonic melody implying two "personas": (1) a cantabile upper stationary voice gravitating around the note E4 over (2) dramatic interventions of an ascending chromatic lower voice progressing from a G# 3 to a B3. The conduction of these independent and opposing melodic layers are emphasized by means of 8th-note rests strategically placed between them (Ex.13).

Ex.13 — Opera recitative in Lesson 4 with two independent contrasting "personas" (upper and lower voices).

Lesson 5 is structured according to an A-B-C-D-E rhapsodic form based on recurrences and development of four basic motifs presented right at the beginning of the piece. These motifs are common to previous lessons (Ex.14): (1) the marching martial half notes with marcato in m.1, (2) the syncopation in m.2, (3) slurred 16th-note groups and their variations in mm.2, 3 and 7, and (4) descending cantabile chromaticism in m.4.

Ex.14 — The four basic motifs of Lesson 5.

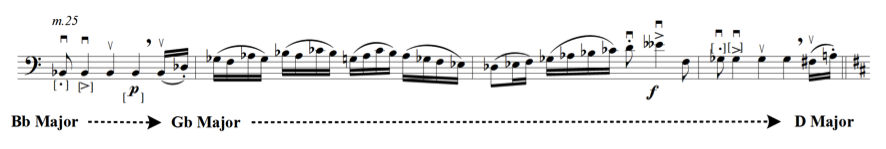

Harmonically speaking, Lesson 5 is the most challenging of the set and, therefore, the one presenting more intonation difficulties. Here, Nunes resorts to a sophisticated chromaticism that probably reflects his familiarity with masterworks by Mozart (Requiem14 and Don Giovanni15) and Bellini (Norma16), whose music he played and sang. Another influence could be Domenico Scarlatti (E Major Sonata K.264)17, the Italian who became a paragon in Portugal, while Brazil was its colony. While in D major, in a short span of time, Nunes covers the chromatic total using altered notes resulting from secondary dominants (D# in m.3, B flat in m.6, C natural in m.14) or non-functional ornamental chromaticism (G# in m.2, E# in m.7). If, within a big picture, Nunes used the circle of fifths to plan his double bass lessons (in a sequence of major-minor key pairs), he refers to it again internally in Lesson 5. By chaining modulations by the interval of a descending major third in a few measures (a procedure to be found in Europe among only the most adventurous composers), he completes the full harmonic cycle in three steps, by turning the key tonic into the mediant of the next key. He first moves from D major to B flat major (m.22), then from B flat major to G flat major (m.25) and, finally from G flat major back to D major (m.28), as shown in Ex.15. It is not a surprise that a very similar procedure is to be found in one of Nunes's role models: Mozart's Don Giovanni.18 Among the opera composers Nunes premiered in Rio was Giuseppe Verdi,19 who was known to explore distant tonalities. Although Verdi's Otello was premiered only 1887 — 40 years after Nunes had already written Lesson 5 — the dark nature of the G flat passage (with six flats!) in the Brazilian music shares the dark atmosphere and cantabile legato of the famous bass section solo in in the Italian opera (preparing the scene in the fourth Act in which Otello kills Desdemona), which gradually moves into tonalities also full of flats such as E flat minor (with six flats!) and C flat major (with seven flats!).

Ex.15 — Lesson 5: Modulations to distant keys by major thirds around the circle of fifths (B flat major-G flat major-D major) anticipates by 40 years the double bass section solo from Verdi's Otello.

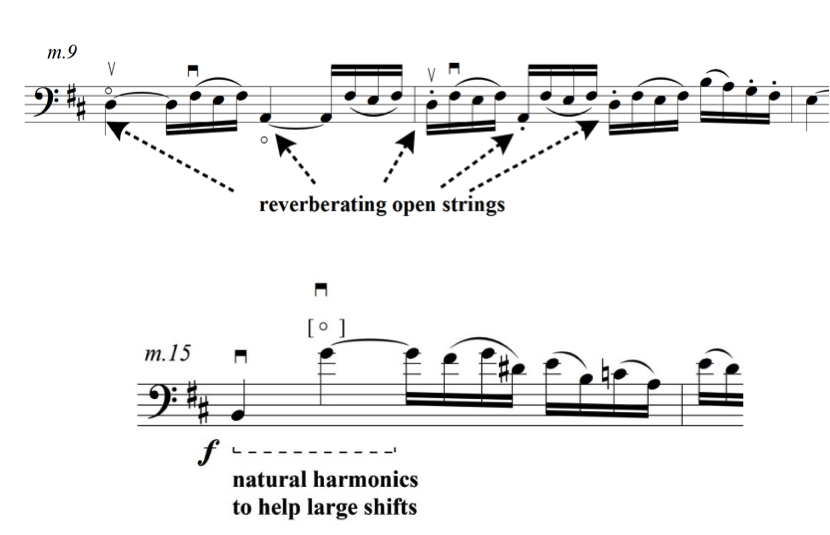

Another aspect of double bass idiomatic writing in Lesson 5 is Nunes's extensive use of reverberating open strings (mm.1, 6, 9,14,16, 22,30, 31 and 32) and natural harmonics (mm.15, 31, in order to help large shifts), as shown in Ex.16. The key of D major on the double bass yields the tonic, dominant and subdominant as the D, A and G open strings, strategically explored by Nunes.

Ex.16 — The reverberation of open strings (m.9) and natural harmonics (m.15) in Lesson 5.

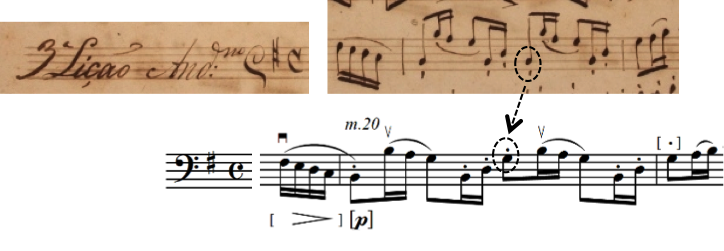

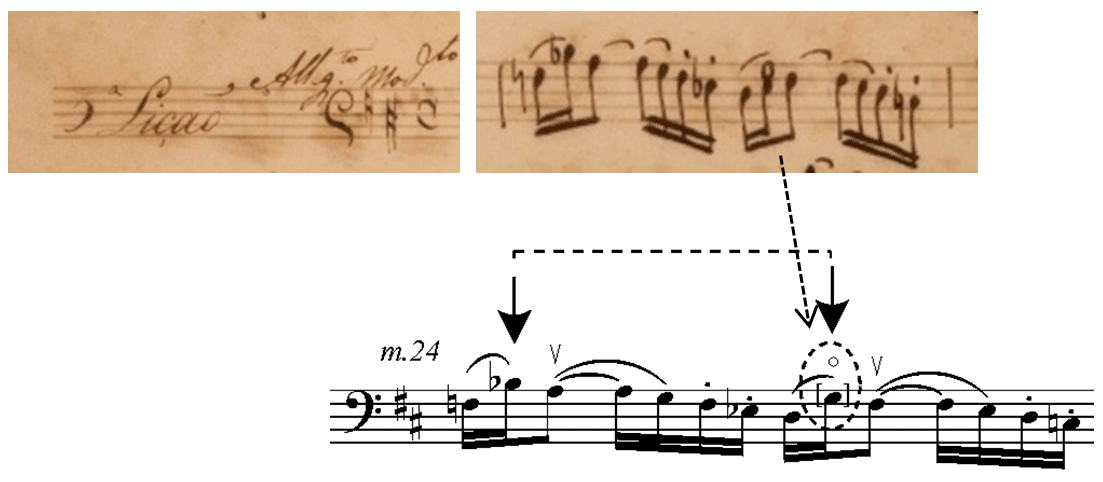

As it happened in the previous lesson, Nunes also structured Lesson 6 as an A-B-C-D-E rhapsodic form. He resorted to five motifs — two used in previous lessons — (1) as the martial dotted 8th note plus a 16th note, (2) 8th notes slurred two-by-two or in staccato — and new motifs — (3) the 32nd-note turn, (4) the 16th-note group ornamented with a grace note, and (5) triplets (Ex.17).

Ex.17 — The five basic motifs of Lesson 6.

In Lesson 6, Nunes wants the bassist to focus on the achievement of clear articulation in operatic ornaments, such as the turns in mm.6, 15, and 16 and a really demanding sequence of eight groups of 16th notes grouped four-by-four with a grace note in the beginning of each (see Ex.24 below). Nunes also wanted the bassist to practice typical opera tempo changes as in the Allegro Moderato of the beginning turns into a "dim. o tempo" ("diminishing the tempo") in m.9 and to a "mto. expressivo" ("molto espressivo") in m.13, then comes back to a "1° Tempo" ("Tempo primo") in m.19, and finally rushes with an "apertando" ("pressing") in m.21, another trait of the cabaletta spirit.

Reviewing consolidated philological references in music, Figueiredo (2012; 2004, p.40) presents the typologies by Georg Feder (eight categories), James Grier (four categories) and Maria Caraci Vela (five categories) to finally propose a taxonomy with seven categories for score editions. Although these authors present common features as far as the edition of scores aiming at performances20 are concerned, a hybrid type of performance edition and musicological edition is proposed in this paper. Here, the option for performance editions was made having in mind that most double bassists still are not familiar with the realization of HIP performance practices in urtext scores. However, all changes in the originals were placed between brackets in the performance editions so the reader can easily identify the editor's interferences. Bowings and indication of strings, absent in the originals, were added at the editor's discretion. Nunes's manuscript is well preserved and reflects a very careful calligraphy. However, formal and harmonic analysis, melodic contour, symmetry, recurrence, and development of thematic materials were used to identify and correct/regularize wrong notes and inconsistences of rhythms, and placement of articulations and dynamics. Next, the main editorial decisions are explained in each lesson.

There are three wrong notes in the manuscript of Lesson 1. At the beginnings of m.11 and m.19, Nunes placed a sharp in the F3 notes to make them lower neighboring tones to G. However, these sharps should not be carried over to the next F3 in the same measures. Thus, they received naturals in the performing edition (Ex.18). Finally, the last note of m.14 should be a B3 and not an A3, since it is part of a descending scale (see Ex.8 above).

Ex.18 - Correction of a wrong note (an F natural instead of an F sharp in m.11) in the performance edition of Nunes's Lesson 1, and suggestions of string, open string signs, dynamics, and alternate bowing and slur.

Only one indication of dynamics appears during the whole Lesson 1: a forte in the last measure, which can be understood as a sign of possible previous dynamics changes. As Nunes focused on few elements in this introductory lesson, terraced forte-piano dynamics pairs, based on the explicit double period pattern, were added to the score. Obvious missing ties and staccato signs were corrected (mm.2, 6 and 28). A ritardando-crescendo pair was added to m.15, allowing the bassist to not reach the opera fermata abruptly (see Ex.8 above). This also serves the purpose of bringing the bow closer to the tip in order to allow for more time to hold that suspension during the up bow. Still in m.15, an open string symbol ("o") was added to the D3 under the fermata as it would be a natural performance practice of the time. Two consecutive up bows were suggested on the second beat of m.22-25, 28, 30, and 32-33 in order to keep the bow closer to the frog and facilitate the staccati in the descending scales.

There was only one wrong note in Lesson 2. The D3 at the beginning of m.16 should be a C3 as it is the turning point of the melodic contour and outlines the F major chord in the second inversion. Symmetry was central for editing this lesson. For example, by crossed comparison (Ex.19), similar decisions were made for the marcati in mm.23-25 (applied to m.19-21) and hairpin pairs (crescendo-decrescendo) signs in mm.19-21 (applied to m.23-25). At a higher level, the staccati in the thematic 8th notes preceding the syncopation in m.13 and the martial pick up in m.29 were applied to the many corresponding inconsistent spots. The emphasis on the second beats of the martial syncopations occupying a whole measure (quarter note - half note - quarter note) were secured with the notation of a down bow on the second beat, which sometimes resulted in two consecutive down bows or two consecutive up bows (mm.2-3). The very inconsistent dynamics notation was mitigated by parallel reasoning. For example, there is no dynamic indication between the piano in the pick up to m.1 and the piano in m.8. Thus, a forte was added to the pick up to m.5 as it marks the second half of the parallel period. Other types of echo structures also received forte and piano indications (m.12 and m.15, m.19 and m.23, m.32 and m.34, m.43 and m.44, m.45 and m.46). Still in relation to bowings, reversed bows (up and down bows on strong and weak beats, respectively) were suggested to make clearer the staccato and slurred notes in m.48.

Ex.19 — Crossed comparison in parallel passages allowed the inclusion of articulation signs (staccato and marcato) and dynamic signs (hairpins) in the performance edition of Nunes's Lesson 2.

There are two wrong notes in the manuscript of Lesson 3. First, the E3 in m.20 should be a G3 (Ex.20), which can be inferred by the other six recurrences of the same note in m.18-20 and the fact that all melodic contours around it converge to this open string, a resource idiomatically used by Nunes. The second wrong note is due to a wrong octave designation: the G4 in m.26 (written in tenor clef) should be a G3 (Ex.21) to not break the descending G major triad after the 16th-note scales (m.24-25) reach their climax. Nunes's use of the open G string motivated the inclusion of the open string and natural harmonics signs in several G and D notes throughout the lesson to emphasize the intended reverberation. Slurs were added to the notes in the feminine cadence in m.4 (G#3-A3) and the appoggiatura in m.28 (E4-D4). Slurs and marcato signs were added to the sequence of syncopations in the last measure (C#4-D4 and A3#-B3) in order to characterize the performance practice of emphasizing the so-called Brazilian syncopation, reflecting the emerging African influence in the popular genres of modinha and lundu (Lima, 2005, p.49). As it happened in Lesson 2, consecutive down bows were added to the martial syncopation of m.2 and m.6. In order to make the realization of the double appoggiatura in m.3 easier, a slur connecting it to the next note (an A3) was added. The echoes of mm.12-14 in mm.15-17 and of mm.18-19 in mm.20-21 led to the inclusion of forte-piano pairs. A forte was also added to m.22 due to the typical symphonic tutti nature of the arpeggio and scales that almost covers the double bass tessitura (B flat2 to G4) used by Nunes on this passage.

Ex.20 — Note correction in in the performance edition of Nunes's Lesson 3: G3 (and not E3) in m.20, based in other recurrences in the passage.

Ex.21 — Another note correction in the performance edition of Nunes's Lesson 3: G3 (and not G4) in m.26, based on the descending arpeggio line contour.

As far as wrong notes are concerned, only one was detected in Lesson 4: the D3 at the end of m.15 should be a D3 sharp in order to work as the leading tone of E minor. To keep the same string timbre, the use of the D string was suggested for the whole chromatic passage in mm.10-13. As it happened in Lessons 1 and 2, martial syncopations were emphasized with down bows on the second beat of mm.1, 2, 5, 6, 18 and 21. Retaking the bow was also suggested in mm.30-31 to keep the bow at the frog and its clear articulation. A crossed comparison of the parallel periods in mm.1-4 and mm.5-8 (Ex.22) made clear the inconsistent notation of their paired dynamics. While the piano and forte in m.1 were added to m.5, the marcato in the syncopation of m.5 was added do m.1. The piano in m.3 was anticipated to the end of m.2 because of its position in m.6, which makes more sense regarding the phrasing.

Ex.22 — Crossed comparison of parallel periods (mm.1-4 and mm.5-8) allowed the inclusion /correction of missing dynamics and articulations in the performance edition of Nunes's Lesson 4.

Although no hairpins were found in Lesson 4, expressive chromatic passages and typical climaxes typically constructed with ascending scales and descending arpeggios motivated the notation of operatic crescendi and decrescendi. The sudden tempo changes, reflecting the aria-caballeta pair, were prepared with suggested ritardandi (m.16 and m.23) and a fermata in the dominant (m.29)before the resolution in the tonic (m.30). In the same passage, in order to connect the trill to the fermata in m.29, the ornament of a turn (typical for the solo string repertory) was suggested. The original staccati in the 16th notes of m.14 were applied to similar passages in mm.16-17. The two layers of the polyphonic melody in m.24-28 were emphasized with the regularization of the contrasting articulations found in the manuscript: staccato for the 8th notes and marcato for the quarter notes.

There are two wrong notes in the manuscript of Lesson 5 (Ex.23). The first note on the second beat of m.19 should be an E#4 sharp instead of an F#4, due to the recurrent pattern of a semitone lower appoggiatura in the same measure and in the previous measure. On the third beat of m.24, the E3 should be a G3 not only because it happens in a melodic sequence of the first beat (an ascending 4th followed by a descending minor 2nd), but also because the little circle on top of it is the symbol of an open string.

Ex.23 — Correction of two wrong notes in the performance edition of Lesson 5: the E#4 (m.19), based on its appoggiatura role; and the G3 (m.24), based on the recurrent melodic pattern and the open string symbol notated in the manuscript.

Patterns in parallel phrasing guided the correction of inconsistent articulation and dynamics in Lesson 5. For example, the marcato accents in m.1 were copied to m.5. Both slurs over the two 16th-note groups in m.17 were copied onto the same patterns in m.18. The slur in the last two notes of m.25 was applied to the correspondent notes in both m.22 and m.28. Likewise, the articulations in the 16th notes of the third and fourth beats of m.30 were copied to the notes on the first and second beats of the same measure. Chromatic stepwise appoggiaturas are a very recurrent trait in Lesson 5 (m.2, 4, 6, 8, 13, 18 and 19), to which slurs were added in order to highlight the typical performance practice of a diminuendo in such cases. As it happened in Lesson 3, Nunes explores the reverberation of open strings in Lesson 5, especially in long notes. Thus, the small circle sign was placed on top of several A2, D3 and G3 notes. To facilitate the reading of the score, the ornament symbol for the turn in m.23 was substituted by its realized form. Although the notation of dynamics is very inconsistent (the first sign appears only in m.6), the symmetry of phrasing and harmonic progressions allowed several suggestions. The emphases caused by large leaps (B2–G4 in m.15 and D3-G4 in m.32) and syncopations (mm.22, 25 and 28) were stressed by retaking down bows. Alternative two-note slurs were given to facilitate the articulation of a G flat major passage on the D string.

There are no wrong notes in Lesson 6. However, two grace notes missing right before the fourth beats of m.7 and m.8 (Ex.24) were added. Alternative slurs and bowings were suggested in the performance edition with the aim of keeping the beginning of all 16th-note groups starting with a down bow and staying near the frog for the purpose of an easier and clearer articulation.

Ex.24 — Correction of two missing grace notes (m.7 and m.8) in the performance edition of Lesson 6, and an added ossia for alternate bowings to help a clearer realization of this virtuosic passage.

To mirror mm.15-16, the notation of the turn in m.6 was changed to its realized form. As it happened in Lesson 4, the suggestion of the operatic aria-cabaletta pair was prepared with a ritardando before the 1° Tempo (i.e., Tempo primo) in m.19. At the same time, a forte was added at this tempo change because it reflects a bravura section with typical 16th note runs with an "apertando" (i.e., an accelerando). Also, there is no other dynamic marking between the forte piano subito in m.18 and the diminuendo at the end of the lesson, in m.24. Two consecutive up bows were suggested at the 16th-note groups in mm.8-9 to keep the bow closer to the frog and help the articulation of this very ornamented passage. Similarities of character and melodic structure guided the inclusion of accents in several passages, such as in mm.1-2, mm.11-12 and mm.15-18.

In a long history associated with European traditions, the discovery of Lino José Nunes's manuscript of 1838 in Brazil opens a new perspective in the appreciation of the double bass outside the Old World. Considered now to be the second double bass method written by a double bassist in the world, the Methodo Prático ou Estudos Complettos para o Contrabaxo is the outcome of an amazing story with a war, politics, and social transformations in a new empire in the New World. Probably the son of a black slave woman and an abandoning European father, Nunes became the most recognized double bass player in the first half of the 19th century in Brazil. Moreover, as an eclectic musician (comfortable in the symphonic, operatic and popular scenes), he excelled not just as a double a bassist, but also as a singer, guitar player, pedagogue, and composer, which contributed to the unique traits and musical qualities of the Methodo's content.

Part I of Lino José Nune's "Methodo" (manuscript provided in Appendix II) reveals several double bass performance practices in Imperial Brazil. It tells us that the Italian 3-stringed instrument tuned in perfect fourths — A2-D3-G3 — was the most common 16-foot string instrument. It also points to the existence of the 4-stringed double bass tuned to G2-A2-D3-G3, with the 4th string tuned only one step below the 3rd string. According to Nunes's time, bassists developed skills to sight-read in all clefs and transpose to all tonalities during the performance, a practice connected to the intense agenda of vocal music, especially the opera.

Part II of Nunes's "Methodo" (manuscript provided in Appendix III) was left incomplete in the middle of the 7th piece. However, it brings music that can be incorporated to the historical double bass repertory: the six complete Lessons. The variety of these unaccompanied pieces was planned by Nunes to provide the students with technical and musical skills to face the demands of the symphonic and operatic repertory. Restricting rhythms, articulations, register, and the harmonic spectrum, he designed Lesson 1 as opening preparatory study allowing the focus on legato versus staccato in scalar phrases, and the interruption of the musical flux for the opera fermata. Lesson 2 explores the contrast between military and operatic cantabile music. Lesson 3 brings virtuosic symphonic scales and arpeggios. Lesson 4 gives the student the opportunity to practice opera elements such as the aria-cabaletta pairing and the cadenza. Lesson 5 is an audacious adventure into chromaticism and distant modulations while anticipating the mood of Verdi's famous Otello double bass solo. Lesson 6 also is in the operatic mood as it is focused in the realization of ornaments and virtuosity in the fiery finale.

The analysis of Nune's performance procedures and compositional process in Part 1 of the Methodo was providential for the preparation of the performance editions of the six Lessons. His use of a structured harmonic plan (at local, medium and large compositional levels), parallel periods and phrasing based on motifs, and their thematic development allowed the correction of wrong notes and compatibility of inconsistencies in articulations and dynamics. The addition of bowings, fingerings and some character indications are intended to provide a more substantial and clearer musical context. The notation of all interferences between brackets allows the double bassist and other readers to identify the original and the edited music.

The authors thank Brian Scoggin, Jim Coker and Craig Swygard for their reading and feedback on the present article.

ANDRADE, Ayres de. Francisco Manuel da Silva e seu tempo: 1808-1865, uma fase do passado do Rio de Janiero à luz de novos documentos. v.1 e v.2. Rio de Janeiro: Tempo Brasileiro, 1967.

ANONYMOUS. Padrão das 10 Sepulturas que há no Capítulo . . . Manuscript from the collection of Arquivo Provincial from Província Franciscana da Imaculada Conceição do Brasil. São Paulo: Manuscript, 1822-?. 124 pages.

BINDER, Fernando Pereira. Bandas Militares no Brasil: Difusão e Organização entre 1808-1889. PPGM/USP, São Paulo, 2006. (Masters in Music).

BRUN, Paul. Histoire des contrebasses a cordes. Preface by Jean_Marc Rollez. Paris: La Flute de Pan, 1982.

BRUNORIO, Frei Róger. Dados do músico Lino José Nunes da Capela Imperial no Convento de Santo Antônio. E-mail from Frei Róger Brunorio, August, 29, 2014.

BUENO, Eduardo. Brasil, uma história: a incrível saga de um país. Preface by Mary del Priore. São Paulo: ática, 2004. 447p.

CABIDO DA CATEDRAL METROPOLITANA DO RIO DE JANEIRO. Certidão de casamento de Lino José Nunes e Mathilde Barbara da Conceição. Rio de Janeiro: Capela Imperial de Nossa Senhora do Monte Carmelo: 31 de março, 1818.

CANçADO, Tania Mara Lopes. O "Fator atrasado" na música brasileira: evolução, características e interpretação. Per Musi. Belo Horizonte: UFMG, 2000. p.5-14.

CARDOSO, André. Um método brasileiro de contrabaixo, do século XIX (1838): Lino José Nunes. Revista Brasileira de Música. v.24, n.2. Rio de Janeiro: UFRJ, 2011. p.425-435.

CARDOSO, Lino de Almeida. O Som e o soberano: uma história da depressão musical carioca pós-Abdicação (1831-1843) e de seus antecedentes. São Paulo: USP, 2006 (Doctor of Social History). 375p.

COHEN, Irving Hersch. (1967) The historical development of the double bass. New York: New York University. 263p. (Doctor of Philosophy).

ELGAR, Raymong. Introduction to the double bass. Princeton, New Jersey: Stephen W. Filho, 1987 (previous edition by the author in 1960).

FIGUEIREDO, Carlos Alberto. Tipos de edição. Debates. n.7. Rio de Janeiro: Centro de Artes e Letras — Unirio: 2004. p.39-55.

______. Os Erros textuais: aspectos e atitudes editoriais. In: Anais do 2° Simpósio brasileiro de pós-graduandos em música: O Contexto brasileiro e a pesquisa em música. Rio de Janeiro: Unirio, 2012. p.102-120.

GáNDARA, Xosé Crisanto. Diccionario de la Música Española e Hispanoamericana. vol. 6. Ed. Emilio Casares Rodicio with Victoria Eli Rodriguez and Benjamín Yépes Chamorro. Madri: Sociedad General de Autores y Editores, 2000.

HARTMANN, Erich. The development of the Double bass and the schools of double bass in Prague, Vienna and Leipzig. Translated by Ruth Cantieny. International Society of Bassists. v.9, n.3. Spring, 1983. p.9-13.

KARR, Gary. Karr talk: Simadlites, Beware!. International Society of Bassists Magazine. Vol.20, n.2. Spring/Summer. Dallas: ISB, 1995. p.54-57.

LIMA, Edilson Vicente. A Modinha e o lundu: dois clássicos nos trópicos. São Paulo: USP, 2010 (Doctor of Musicology).

_____. A Modinha e o lundu no Brasil: as primeiras manifestações da música popular no Brasil. Música erudita brasileira. Textos do Brasil. Org. by Ricardo Bernardes. Brasília: Ministério das Relações Exteriores, 2005. pp.41-46.

MATTOS, Cleofe Person de. 2° Centenário do nascimento de José Maurício Nunes Garcia (1767-1830): exposição comemorativa. Rio de Janeiro: Biblioteca Nacional, 1967 (Manuscript memo by Father José Maurício Nunes Garcia, exhibited as Document 135).

MONTGOMERY, Michael. Training as a teacher in Argentina, ways to teach young bassists: where to turn for ideas. Bass World, The Magazine of the International Society of Bassists. Child's Play. Ed. by Virginia Dixon. Vol.34, n.3. Dallas: ISB, 2011.p.5-8.

MILLER LARDIN, Heather. Michel Corrette's Méthodes pour apprendre à jouer de la Contrebasse à 3. à 4. et à 5. cordes, de la Quinte ou Alto et de la Viole d'Orphée: A Translation with Commentary. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University, 2006 (Doctor of Musical Arts).

NEVES, José Maria. A orquestra Ribeiro Bastos e a vida musical em São João del-Rei. Rio de Janeiro: Fundação Roberto Marinho, 1984.

PLANYAVSKY, Alfred. The Baroque double bass violone. Translated by James Barket. London: Scarecrow Press, 1998.

SADIE, Stanley (ed.). The Norton/Grove concise encyclopedia of music. Assist. Editor Alison Lathan. New York: Norton, 1988.

SANKEY, Stuart; APPLEBAUM, Samuel; ROTH, Henry. Stuart Sankey. In The Way they play. Book 6. Neptune, N.J: Paganiniana Publications, 1976. pp.65-86.

SAS, Stephen. A History of double bass performance practice: 1500-1900. New York: Juilliard School, 1999. (Doctor of Music)

SILVA, Marcos Vieira; CASTILHO, Sabrina Simões. Performance musical em corporações dos Campos das Vertentes e sua articulação com tradições culturais. Memorándum, v.21. Belo Horizonte: UFMG, 2011. p.217-237.

TARLTON, Neil. Music reviews. Double Bassist. Londres, v.8. Spring, 1999, p.77.

TARUSKIN, Richard. Bel canto. In: Oxford History of Western Music / Music in The Nineteenth Century / Chapter 1 - Real Worlds, and Better Ones. vol.3. pp.1-11. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010a (Access in June, 20, 2014; www.oxfordwesternmusic.com).

______. Heart throbs. In: Oxford History of Western Music / Music in The Nineteenth Century / Chapter 1 - Real Worlds, and Better Ones. vol.3. pp. 1-9. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010b (Access in June, 20, 2014; www.oxfordwesternmusic.com).

______. Music as a social mirror. In: Oxford History of Western Music / Music in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries / Chapter 9 - Enlightenment and Reform. vol.2. pp.1-4. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010c (Access in June, 20, 2014; www.oxfordwesternmusic.com).

______. Scarlatti, at last. In: Oxford History of Western Music / Music in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth Centuries / Chapter 7 - Class of 1685 (II). vol.2. pp.1-9. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2010d (Access in June, 20, 2014; www.oxfordwesternmusic.com).

TINHORãO, José Ramos. Música Popular: os sons que vem da rua. Rio de Janeiro: Author's edition, 1976. 190p.

WOLFF, Christoph. Mozart's Requiem: historical and analytical studies, documents, score. Translated by Mary Whitthall. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994.

BILLè, Isaia. Nuovo metodo per contrabasso a 4 e 5 cordes. Part 1. Milan: Ricordi, 1922.

CORDEIRO, João Rodrigues. Fantasia para Contrabaixo (1869). Ed. by Sérgio Dias. Juiz de Fora: Author's electronic edition, 2000.

CORRèTE, Michel. Mèthodes pour apprendre a jouer de la contre-basse a 3 a 4 et 5 cordes, de la quinte ou alto et de la viole d'orphée. Genebra: Minkoff Reprint, 1977 (previously published in Paris: L'Edition de Paris, 1773 [1781]).

DODERER, Gerhard (Org.). Modinhas luso-brasileiras. Serie Portugaliae Musica. Lisboa: Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian, 1984.

FRÖHLICH, Joseph. Vollständige theoretische-praktische Musikschule für alle beym Orchester gebräuchliche wichtigere Instrumengte. Würzburg: manuscript, 1829.

HAUSE, Wenzel. Méthode complète de contrebasse a 4 cordes — Parts 1 and 2. Paris: ?, c.1828.

______. Méthode complète de contrebasse a 4 cordes — Part 3. Prague: ?, 1840.

MARANGONI, Giuseppe M. Scuola teorico-pratica del contrabasso. vol.1-7. Ed. Revised by F. Francesconi. Bolonha: Edizioni Bongiovanni, 1929.

NUNES, Lino José. Methodo Prático ou Estudos Complettos para o Contrabaxo. Facsimile of the original located at Alberto Nepomuceno Library, at Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro. Rio de Janeiro: (manuscript), 1838.

1 Orquestra Lira Sanjoanense (circa 1776) and Orquestra Ribeiro Bastos (circa 1790) in the town of São João del Rey (State of Minas Gerais, Brazil) are considered the two earliest symphonic orchestras still in activity in the Americas (Silva and Castilho, 2011, p.220; Neves, 1984, p.197-198).

2 Although Nunes's first name is written as "Lino Jozé" in the manuscript, we are using the spelling "Lino José" according to the musicological tradition in Brazil to use modern Portuguese.

3 Nunes's burial place (Santo Antônio Convent, Rio de Janeiro) and death year (1847) were given by Mattos (1997, p.220) and Andrade (1967, vol.2, p.135), respectively, based on the year the name of the musician " . . . was withdrawn from the Royal Chapel's pay roll . . . ". The latter is now confirmed with the disclosure by Frei Róger Brunorio (2014) of the burial book "Padrão das 10 Sepulturas que há no Capítulo" (page 1 and back of page 34), which brings Nunes's correct death date and place: September, 5, 1847; 6th grave of the cloister square.

4 Although Nunes's baptism certificate has not been found yet, his marriage certificate (Cabido . . . , 1818) and death certificate (Anonymous, 1822-?) bring minimum information about his parents and death date.

5 The manuscript of Nunes's"Methodo" was found at the Alberto Nepomuceno Library, located at Federal University of Rio de Janeiro and considered the largest repository of music manuscripts in Brazil.

6 Another story relates medicine to the history of double bass in Brazil a couple of decades after Nunes's Methodo Pratico as João Rodrigues Cordeiro (1826-1881), a Brazilian doctor and amateur bass player wrote his Fantasia para Contrabaixo e Orquestra de Cordas (Fantasy for double Bass and String Orchestra) in 1869 (Tarlton, 1999, p.77; Cordeiro, ed. by Sérgio Dias, 2000).

7 The Austrian Sigismund Neukkomm (1778- 1858), one of the foremost pupils of Michael and Joseph Haydn, was a major musical figure in Brazil, living there for 6 years (1816 to 1821).

8 1830 and 1831 were the fateful years for the Royal Chapel Orchestra. In 1830, the chapel masters were dismissed; first Marcos Portugal on the 7th of February and, then, Padre José Maurício Nunes Garcia on the 18th of April. In June of 1831, the Orchestra was officially extinct by a Decree of the Justice Minster Manuel José de Souza França. The orchestra and full choir were reestablished only in 1843.

9 After the extinction of the Royal Chapel in 1831, only four instrumentalists were kept being paid by the service: double bassists Lino José Nunes and José Venâncio de Assunção, and bassoon players Alexandre José Baret and Francisco da Mota.

10 In 1787, British William Beckford (quoted by Doderer, Org., 1984, p.IX) mentioned the custom of "voluptuous" modinhas being sung by two men, one normally dressed as a man and the other as a woman.

11 The difficulty to press down the strings onto the double bass fingerboard lead to solutions such as M. Langlois's pinching the strings between the thumb and forefinger and Giovanni Bottesini's pulling the string aside without touching the fingerboard (Cohen, 1967, p.159).

12 The octave designation used in this paper considers the central C of the piano as C4 (Sadie, 1988, p.583). Since the double bass is a transposing instrument, the actual pitch when it plays a C4 is a C3.

13 The gaps in the double bass line when doubling the cello were common even in the late 19th century, as in Brahms's Symphony # 2 of 1877, for example (Brun, 1982, p.205).

14 Wolff (1994, pp.96-99) mentions the unparalleled harmonic density of the Requiem.

15 Taruskin (2010c, p.2 of 4) talks about the " . . . the strains of an orchestral passage making frantic modulations around the circle of fifths, but ending on a diminished-seventh chord that coincides with Don Giovanni's fatal thrust".

16 Taruskin (2010a, p.7 of 11) narrates a chromatic passage in the opera Norma: "But then the tide of dissonance suddenly surges. Every beat of the seventh bar emphasizes the dissonant seventh (or the more dissonant ninth) of the dominant harmony, and the resolution to the tonic takes place against a chromatic appoggiatura to the third of the chord that clashes against its neighbor in the accompaniment as if G minor were vying with G major."

17 Taruskin (2010d, p.4 of 9) reveals Scarlatti's a local level chromaticism in his E Major Sonata K.264, which " . . . contains chords in whose roots lie the very maximum distance — namely, a tritone — away from the tonic on a complete (rather than diatonically adjusted) circle of fifths."

18 Wolff (1994, pp.96-99) calls attention to one of the innovations Mozart introduced with Don Giovanni, i.e. modulations by thirds to the mediant and submediant.

19 According to the detailed lists of operas staged in Rio prepared by Andrade (1967, vol.1, pp.113-126; vol.2, pp.121-130), Lino José Nunes, as the foremost double bassist of his time, may have participated in the premiere of Verdi's Ernani at São Pedro de Alcântara Theater in June, 16, 1846 (Andrade , 1967, v.2, p.124).

20 Figueiredo (2004. p.39-55) sees common features among these authors that can be related to what is proposed here as a performance edition: the "corrected impression in modern notation " and "musicological and practical edition" of Georg Feder, the "interpretive edition" of James Grier, the "practical edition" of Caraci Vela, and the "open edition" of Walther Dürr.

BILLè, Isaia. Nuovo metodo per contrabasso a 4 e 5 cordes. Part 1. Milan: Ricordi, 1922.

CORDEIRO, João Rodrigues. Fantasia para Contrabaixo (1869). Ed. by Sérgio Dias. Juiz de Fora: Author's electronic edition, 2000.

CORRèTE, Michel. Mèthodes pour apprendre a jouer de la contre-basse a 3 a 4 et 5 cordes, de la quinte ou alto et de la viole d'orphée. Genebra: Minkoff Reprint, 1977 (previously published in Paris: L'Edition de Paris, 1773 [1781]).

DODERER, Gerhard (Org.). Modinhas luso-brasileiras. Serie Portugaliae Musica. Lisboa: Fundação Calouste Gulbenkian, 1984.

FRÖHLICH, Joseph. Vollständige theoretische-praktische Musikschule für alle beym Orchester gebräuchliche wichtigere Instrumengte. Würzburg: manuscript, 1829.

HAUSE, Wenzel. Méthode complète de contrebasse a 4 cordes — Parts 1 and 2. Paris: ?, c.1828.

______. Méthode complète de contrebasse a 4 cordes — Part 3. Prague: ?, 1840.

MARANGONI, Giuseppe M. Scuola teorico-pratica del contrabasso. vol.1-7. Ed. Revised by F. Francesconi. Bolonha: Edizioni Bongiovanni, 1929.

NUNES, Lino José. Methodo Prático ou Estudos Complettos para o Contrabaxo. Facsimile of the original located at Alberto Nepomuceno Library, at Universidade Federal do Rio de Janeiro. Rio de Janeiro: (manuscript), 1838.Obs: The performance editions of the six complete Lessons for unaccompanied double bass (pp. 11-15 of the manuscript) are available at the ISB site for fund raising to help bass projects)

© 2003 - 2026 International Society of Bassists. All rights reserved.

Items appearing in the OJBR may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the International Society of Bassists, and advance notification of the editors of the OJBR.

Any redistributed form of items published in the OJBR must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in The Online Journal of Bass Research in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] in [MONTH/YEAR], and it is republished here with the written permission of the International Society of Bassists.

Libraries may archive issues of OJBR in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of the OJBR and the International Society of Bassists.

Citations to articles from OJBR should include the URL as found at the beginning of the article and the paragraph number; for example:

Volume 3

Alexandre Ritter, "Franco Petracchi and the Divertimento Concertante Per Contrabbasso E Orchestra by Nino Rota: A Successful Collaboration Between Composer And Performer" Online Journal of Bass Research 3 (2012), <http://www.ojbr.com/volume-3-number-1.asp>, par. 1.2.Volume 2

Shanon P. Zusman, "A Critical Review of Studies in Italian Sacred and Instrumental Music in the 17th Century by Stephen Bonta, Burlington, VT: Ashgate Publishing Co., 2003." Online Journal of Bass Research 2 (2004), <http://www.ojbr.com/volume-2-number-1.asp>, par. 1.2.Volume 1

Michael D. Greenberg, "Perfecting the Storm: The Rise of the Double Bass in France, 1701-1815," Online Journal of Bass Research 1 (2003) <http://www.ojbr.com/volume-1-complete.asp>, par. 1.2.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.