Abstract: In the period 1849 -1851, a collection of articles by A. Müller and F.C. Franke appeared in the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik, which discussed various aspects of double bass playing. The two double bassists agreed on some points, including that the double bass has a very important role in the orchestra, that there was a lack of good double bass players at the time, and the general characteristics of a good instrument. But, they debated other subjects, such as playing stance, left hand technique, bow technique, the necessary components of daily practice, and the common practice of simplifying double bass parts. Their discussion on these topics has implications for historically informed performance, especially in regard to the performance of Beethoven's symphonies, while also raising questions regarding technical development that are relevant to modern double bassists who play all styles of music.

August Müller and Friedrich Christoph Franke were two German double bassists in the mid-nineteenth century who were concerned about the state of double bass playing in their time.i While it seems that they never met each other, they did correspond with one another, in a manner of speaking, through articles published in the NZfM.ii These articles appeared in the period from 1848 - 1851 and deal with various subjects related to double bass playing. Franke and Müller's discussion in these articles provides a great deal of insight, not only about nineteenth-century double bass technique, but also about the construction and set-up of instruments, how double bassists were trained, and orchestral performance practices.

August Müller, born in 1808, was a double bassist for the court orchestra at Darmstadt from 1825 until his death in 1867 and eventually rose to the position of its principal double bassist. Müller made his solo debut in Darmstadt in 1836 and soon gained renown performing in London and Paris.iii Between 1847 - 1864 Müller wrote a number of articles for the NZfM, including the extended series, "On the double bass and its use, with regard to the symphonies of Beethoven," which appeared in eight installments between June 1848 and March 1849.iv In his first installment, Müller listed all the existing method books he knew, and this list was essentially responsible for initiating the written debate between himself and Franke.v

Friedrich Christoph Franke was born in 1804 in the town of Sangerhausen and joined the Prussian military in 1821 as a musician in the Alexander-Regiment of Berlin. In 1824, he gained employment as a double bassist in the orchestra of the Königsstädtisches Theater in Berlin, where he performed a self-composed concertino with variations in 1830. Franke became the principal double bassist of the Duke of Anhalt's court orchestra in Dessau in 1834, and later joined the court orchestra in Strelitz.vi His contributions to the NZfM indicate that he stayed in Dessau until at least 1851.vii Franke's method book, Instructions for Playing the Double Bass, was first published in 1845, and later reprinted in 1874.viii

An anonymous letter appeared in the NZfM in October 1848 that inquired why Müller had neglected to include Franke's method book in his list of existing double bass tutors, and invited him to include a discussion of the method in a later article.ix Müller obliged, though his review of Franke's method did not appear until after his series on playing the double bass in Beethoven's Symphonies was completed. Meanwhile, Franke wrote an article in December 1848 that again called attention to the omission of his method, while also highlighting the points in Müller's articles with which he disagreed. After Müller wrote a critical review of the method in June 1849, Franke provided one last rebuttal in January 1851, and this concluded the exchange as far as it was documented in the NZfM.

Franke and Müller's unique dialogue reveals a great deal about the state of double bass playing circa 1850: information that is valuable today to those in the field of historically informed performance, as well as to bassists playing any style of music who are looking to explore non-standard playing techniques as a way of enhancing their performances. While the diversity in historical technique already becomes obvious from looking at various sources that discuss double bass playing from the late-eighteenth to mid-nineteenth centuries, their differences can now only be discussed and evaluated from a modern point of view.x Reading Franke's and Müller's opinions of each other's instructions however, offers a contemporaneous critical review of each author's works. Their discourse yields detailed explanations and justifications, allowing modern players to more deeply understand the two bassists' ideas about playing.

This examination of Franke's and Müller's playing methods will focus primarily on the points about which the two authors disagree and on practices that deviate from modern trends in double bass performance practices. The following subjects will be discussed in roughly the same order in which they appear in Franke's and Müller's own publications: the role of the double bass, the state of double bass playing, characteristics of the instrument, playing stance, left hand technique, bow technique, the components of a practice regimen, and suggestions for performing Beethoven's symphonies. These instructions will be explored in relation to their relevance to modern double bass playing in the contexts of both general playing technique and historically informed performance.

While Franke and Müller disagreed on many points, they were both passionate exponents of the double bass and prefaced their instructions for playing the instrument with a discussion of its importance. In his method, Franke explains that the bass line determines the harmonic progression and thus the intrinsic value of music, and that therefore a good bass section is necessary for the effective execution of a work. He praises the double bass as an instrument with the fullness and majesty of a strong organ pedal, as one that no other instrument can match in its depth and diversity of tone, and as one that is able to equal the nuance in performance of all other instruments.xi Müller puts it more briefly, and states that an orchestral performance in which the bass is poorly heard is "imperfect."xii

That the bass line is the foundation of a piece of music has been a widely accepted rule throughout Western musical history, and sources from the nineteenth century in particular devote paragraphs or even entire sections to describing the double bass's important role in ensemble situations. The German music pedagogue Franz Joseph Fröhlich called a good double bassist the "soul of all music."xiii Johann Joachim Quantz, who though he is most famous for his treatise On Playing the Flute, also studied the double bass and numerous other instruments, and wrote that "many persons do not appreciate how valuable and necessary it is in a large ensemble when [the double bass] is well played. . . . Especially in an orchestra, where one person cannot always see the others or hear them well, the double bass player, together with the violoncellist, forms the point of equilibrium, so to speak, in maintaining the correct tempo."xiv More emphatically, Jacques Claude Adolphe Miné begins his double bass method with the words, "The double bass is the lowest instrument of the orchestra. Its power makes it indispensable for nourishing and binding the masses of harmony found in symphonic music."xv That Franke, Müller and so many others felt the need to include such statements in their discussions of the instrument suggests that perhaps double bassists of the time were inadequately, and noticeably so, performing the role so inherent to their instrument. Further evidence of this deficit appears in Franke's and Müller's writings.

Both Franke and Müller comment resentfully on the apparent lack of good double bass players, and present suspected causes.xvi Each author lists the same primary reasons for this unfortunate deficiency:

Training in double bass playing is not up to the same standards as that of other instruments:

Müller writes that there are no completely sufficient method books or truly capable teachers, and that while some conservatories are in the early stages of attempting to remedy this discrepancy, other institutions do not take enough interest in the double bass.xxii He compares double bass training to the preparation of sourdough bread, in which the same old piece of dough is kept and kneaded for generation after generation.xxiii Franke agrees that there is a lack of good double bass methods, and adds that those that exist are not widely disseminated, which he claims is demonstrated by Müller's unfamiliarity with his method.xxiv

The double bass is not granted enough financial priority:

Franke argues that based mainly on economic grounds, double bass players are not sufficiently trained before they are sent to work in orchestras.xv Müller suggests that a reward should be offered for someone to write a good double bass method, but that he believes that most publishers would not even accept a double bass method for free.xxvi

Franke and Müller are not alone in pointing out the deficiencies of double bassists in the nineteenth century, or in laying the blame on external factors such as instruments or orchestral management. Fröhlich, for example, reprimands orchestras for their destructive habit of employing double bassists who damage the character of the bass line with superficial, cold or tasteless playing.xxvii Hause also notes the scarcity of good method books in the introduction to his own method.xxviii

Franke and Müller both stress that double basses must be constructed with quality materials and the proper proportions. Franke writes that while the size of instruments varies, they must still be proportionate in shape, size, and strength.xxix Müller applies this concept even further to strings. He says that the strings must be the correct distance from the fingerboard and from each other in order to prevent strings from colliding or rattling against the fingerboard while playing forte. Strings should also be the appropriate thickness for the instrument, relative to its size and the thickness of its constitutive wood. He further recommends using Italian-made strings, which he explains are superior to German and French strings because they are made from better materials, and are twisted more tightly, making them more flexible. Lastly, Müller prescribes a metal-wound A string because it is thinner and thus produces a clearer tone than an unwound A string.xxx

Franke and Müller also have similar ideas about what characterizes a good bow, namely, that it should be long and heavy enough to be effective on the very thick strings of the double bass. The two disagree however, on whether it is advantageous to add even more weight to the bow by filling the tip with lead. Franke suggests doing this in his method, and even stands by the idea after Müller states in his review of Franke's method that weighting the tip inhibits easy and free movement.xxxi

While Franke's and Müller's instructions provide a very clear picture of the ideal double bass in accordance with the state of instrumental development at the time, further observations reveal that such instruments were in fact quite rare. Franke remarks that a good instrument and good bow are rarely considered essential for double bass players, and offers this as yet another reason for the subpar performance of double bassists in many orchestras. He argues further that the lack of appreciation for both players and instruments does not inspire young artists to devote themselves to the double bass.xxxii Müller also observes that many orchestras suffer from the employment of mediocre instruments, whose sound is often lost in the orchestra and lacks resonance, or even worse, which produce a "hammering of the strings."xxxiii He writes that double basses crafted by the old Italian masters are rare, and that one usually hears instruments that are made of thin, low-quality wood and have improperly positioned bridges and fingerboards.xxxiv

Franke and Müller each provide instructions for holding the instrument. In his method, Franke describes two methods of standing with the instrument: one for larger players and one for smaller players. His recommended stance for larger people involves standing with the left foot behind the bass at the middle of the instrument, and the right foot a bit forward and turned slightly outward so that the leg makes contact with the edge of the lower bout of the instrument. In this position, Franke instructs the player to support his body weight on his left foot so that he can turn the instrument with his right knee to be able to reach all the strings. To play on the lower strings, the player should turn the bass forward a little and meanwhile lean the body slightly to the right. He warns however, that these movements should not be noticeable to the audience, and that a player's posture should always be upright and at ease. For smaller players, Franke offers a slight variation to this position; the bass should be turned more towards the player, the right foot should support his body weight, and the left foot should be placed behind the instrument in such a way that bending the knee forward slightly turns the instrument, thereby allowing access to all four strings.xxxv

Müller writes that in order to have the same ability as violinists and cellists to move the arms freely while playing, a player must hold the double bass with the inside of the left knee and the upper part of the right calf, with his right foot turned outward.xxxvi He further explains that one must have an endpin that is long enough to allow standing in this position, and also advises bass players to maintain a dignified posture since playing while standing makes them more visible to audiences.xxxvii In reference to Franke's method, Müller states outright that supporting the body on the right foot and leaning to the right to play the lower strings is wrong. According to Müller, a double bass player must always stand up straight and support his weight on his left foot, for if the player supports himself on his right foot, he will lose the freedom to move his right arm. He also advises smaller players to use smaller basses, or to choose another instrument entirely, rather than allowing them to hold the instrument in a different manner as Franke suggests.xxxviii

Neither Franke's nor Müller's suggested manner of holding the bass is popular among performers today. Aside from the fact that many modern double bassists choose to play while sitting, even those who stand would not promote supporting most of the body's weight on one leg, or suggest turning the bass with one's leg when moving from the higher to the lower strings and vice versa. However, some of these methods' principles have survived to the present day: Müller's assertion that one must not hold the double bass up with the left hand, and Franke's observation that how someone holds the double bass depends on the size of both the player and the instrument are still two of the most basic fundamentals of modern double bass technique.xxxix Other aspects of these standing positions may be more specifically applicable to historically informed performers. For instance, it is clear that both Müller and Franke held the bass in a fairly upright position, as their legs would otherwise not be close enough to the instrument to hold it in place and to turn it in order to access all four strings. In such a position, the bow exerts force horizontally across the strings more than down into the strings, a tendency that diminishes if the instrument is positioned at an angle. Historical cello and viola da gamba players also held their instruments fairly upright, a result of holding their instruments in place with their legs since they did not have endpins. The influence of this position on how the bow makes contact with the strings is part of the modern 'HIP' sound, which is commonly described as more open or resonant, but with less projection. Modern 'HIP' double bassists should therefore be cautious if they choose to sit or stand with the bass in a more angled position, and adapt their bowing accordingly.

Perhaps the most extreme contrast between Franke's and Müller's methods lies in their ideas about left hand technique and fingerings. Franke advocates the equal use of all four fingers, while Müller outlines a 3-finger system, which most double bassists today would recognize as standard fundamental technique. When evaluating their arguments, it is important to view these two methods within the context of the development of both the double bass and its playing technique. Methods dating from before Müller and Franke's discussion outline a variety of fingerings. Some employ all four fingers (e.g. Corrette and Miné, though unlike Franke, their methods suggest using either the second or third finger in different situations, instead of using these fingers for consecutive semitones in one position); while others exclude a finger in the lower positions (e.g. Hause and later Simandl, who outline strict 1-2-4 fingerings, and Bonifazio Asioli, who established the Italian 1-3-4 system); and still others use only first and fourth fingers (e.g. Fröhlich, and Giovanni Bottesini at times).xl This last 2-finger, or fisticuff, fingering system was a necessity for playing on thick strings that were strung quite high over the fingerboard; however, as instruments and strings developed, the practice was abandoned early in the nineteenth century.xli

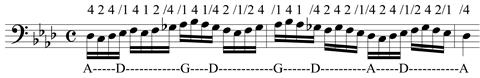

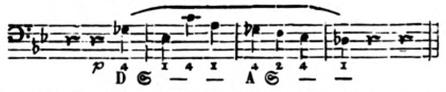

Franke claims that nothing is more natural than being able to reach all the notes between the open strings in one position, and that this yields the most reliable results for executing passagework.xlii Using all four fingers also allows the player to play more notes with fewer shifts, which Franke points out is advantageous even according to Müller's own rules.xliii Franke also implies that 3-finger technique is a byproduct of lower standards, which violinists and cellists would never accept; he asks, "What would you say if a violinist or a cellist would regress to this idea, try to declare a finger disabled and explain that a fingering derived from this is correct and useful?"xliv Franke uses an excerpt from the storm scene of Beethoven's Sixth Symphony to demonstrate the advantages of his fingering system. He provides two fingerings for the excerpt, each of which allows the entire passage to be performed without shifting (see figure 1).

Müller ardently disapproves of Franke's fingering system. He even goes so far as to say that the fingering rules that Franke outlines in his method prove that he does not have an "ex fundamento " understanding of the character of the double bass.xlv Müller argues that one can see by looking at the hand that it is only suited to reach two semitones, and that it is only possible to reach three semitones within one position by stretching out the hand and fingers in an unnatural way that weakens the hand. He goes on to say that the third finger is not an independent finger and should therefore only be used in conjunction with another finger. This finger is more useful when it supports the fourth finger, which is naturally weaker than the second.xlvi As an exception, Müller prescribes the use of the third finger in two situations: when playing whole-tone trills, for which he says using the whole hand would be too cumbersome; and to play the notes that lie one octave above each open string because the fourth finger is too short to reach them.xlvii

Figure 1. Franke's fingering options for Beethoven, Symphony no. 6, movt. 4, mm. 41 - 43.xlviii

While Müller does not include the excerpt from the Sixth Symphony discussed above in his collection of articles on playing Beethoven's symphonies, his most likely choice of fingering can be extrapolated from the rules and examples he presents in his articles (see figure 2). If one uses the conventional 3-finger system advocated by Müller, it is not possible to play more than three or four consecutive notes without shifting, and sometimes only one note lies between two shifts. Whether this fingering or Franke's expends less energy is largely a matter of personal preference, and depends on various factors. Someone with a relatively broad hand or long fingers might be able to execute Franke's fingerings with little trouble, while someone with a smaller hand might prefer shifting over stretching to reach notes. Moreover, training will have an impact on preference as well. Those who have learned the modern technique known as pivoting to expand their reach within a single position, and who use all four fingers independently, would prefer Franke's fingering; while players who never use the third finger in the lower positions would likely struggle to suddenly incorporate it in this passage. Nevertheless, it is not necessary to adhere to one method just because it is the most familiar. Double bassists who practice both systems, as well as other non-conventional fingerings, have the advantage of being able to choose whichever fingering is most useful in any given situation.

Figure 2. Fingering Müller would likely choose for Beethoven, Symphony no. 6, movt. 4, mm. 41 - 43. Shifts are indicated by a slash ( / ).xlix

Though Müller's fingering system more closely reflects standard modern technique, he provides the rather questionable justification that double bassists have already learned how to execute all the difficult passages they might come across with the 3-finger method.l Unfortunately for Müller, this argument contradicts his earlier complaint that double bass training is like old sourdough that is made into loaf after loaf of the same bread, instead of developing and progressing. Franke also criticizes Müller's reasoning and maintains that using the third finger does not reduce clarity in fast passages.li There is no way to definitively prove that one method or the other is more 'correct' for every bass, player, and situation. Whether dealing with the twenty-first, nineteenth, or any other century, double basses come in a variety of sizes, with diverse set-ups; and players have different hand sizes, as well as varying levels of agility, flexibility, strength, and coordination: factors which lead them to prefer different fingering systems.

Another dispute regarding left hand technique has to do with how the fingers contact the string. Franke writes that double bassists should not play on their fingertips as violinists do, but should instead extend the first segment of the finger and place it firmly on the string so that it cannot escape and gives a pure and melodious sound. Franke also indicates that the first segment of the thumb should be applied to the neck as a counter pressure, more or less across from the position of the middle finger.lii

Müller disagrees and bluntly states that Franke's method is wrong, and that the strings should be depressed with the meatiest part of the finger, which is something in between playing on the very tips, as violinists do, and laying the finger across the string as Franke suggests. He also rejects Franke's prescribed placement of the left thumb, stating that the first joint of the thumb should be placed on the right side of the neck.liii

Franke responds that his and Müller's suggested hand positions are essentially the same because the difference in the position of the thumb and fingers is hardly more than the width of a hair.liv It is indeed possible that Franke's and Müller's finger placements are in fact almost identical, and that the two simply interpret the terminology differently, specifically with regard to what it means to 'lay' the finger across the string. Their opinions on the matter of thumb placement differ more clearly. Müller's method of placing the first knuckle of the thumb on the right side of the neck puts the neck more deeply into the hand than Franke's method of placing only the tip of the thumb behind the neck.

From these descriptions alone, since diagrams or illustrations are absent in both sources, it seems that Franke's hand position reflects what most modern bassists would consider proper technique. However, his statement that the thumb applies a counter pressure goes against the currently prevailing rule that in order to prevent injury, the thumb should be relaxed and the strings should be depressed by the weight of the player's hand and arm — and not by pressing the fingers down, holding the instrument with the thumb, or using any significant muscular force.

Franke and Müller each adamantly contend that their own way of holding the bow is correct and that the other's is unnatural, though they follow the same fundamental principles and differ only slightly in mechanics. Both Müller and Franke describe an underhand (German) bow hold with the thumb placed over the stick, one finger serving to direct the stick, and two fingers placed in the frog. This leaves one finger without a clear purpose, which leads to the discrepancy that arises between their two holds.

Franke chooses to place the little and ring fingers in the frog and uses the middle finger to direct the bow, which leaves the index finger free to rest somewhere between the middle finger and thumb while providing support.lv Müller, on the other hand, uses the index finger to direct the bow, places the middle and ring fingers in the frog, and leaves the little finger free to settle under the frog.lvi

Müller calls Franke's bow hold "unnatural" and "forced" because it causes the weight of the hand to fall mostly on the stick rather than the frog, which Müller claims causes the player to "hack" and "saw" with the bow.lvii Franke counters this statement by listing five objections to Müller's method:

In practice, the primary difference between the two methods is that Müller's bow hold creates the sense of holding the frog, while Franke's feels like holding the stick. Modern bow holds follow Franke's example in this respect, and give one the sense of holding the stick more than the frog. That being said, since the frogs of modern German bows are generally shorter than those in Müller and Franke's time and thus lack the space for two fingers, most modern methods involve placing the index and middle fingers on the stick, the ring finger in the frog, and the little finger underneath the frog, which can perhaps be seen as an amalgamation of Franke's and Müller's bow holds.

Müller also criticizes some of Franke's instructions for different bow strokes. While Franke writes in his method that one performs staccato by lifting the bow from the string between notes, Müller insists that the bow must stay on the string during the short pause between notes in order to keep the string from ringing, and to prepare for the next stroke. According to Müller, a bouncing bow is only used for fast repeated notes in piano.lix Franke readily accepts this correction, but is less forgiving of Müller's comment that his instructions for col legno should have been omitted because the technique is "unpoetic" and outdated.lx Franke defends himself by saying that col legno is an existing expression, and is therefore rightfully included in his method.lxi

Both authors advise a method of practice meant to help aspiring double bass students rise to a professional level of performance. Franke's method book provides a detailed guide to this training and includes exercises in every key, for all types of bowings, and in various styles. He also includes examples from the orchestral repertoire, and sections on ornamentation and accompanying recitatives. In his review, Müller commends the method for having good exercises that are presented in a reasonable order, and that address the various aspects of playing. He also compliments in particular the sections on supplementary subjects such as ornamentation, compositional styles, and accompanying recitatives; the latter of which, he states, no one else has written about before.lxii

Though Müller did not write a method in a traditional format, he nonetheless includes suggestions for a routine of daily practice in the second installment of his extended article; Müller's routine consists of:

Franke writes that Müller's routine is too limited, and suggests adding both exercises in fourths, fifths and sevenths, as well as more bowing styles than just slurs.lxiv While the addition is not extreme, it does indicate that Franke has a more technical approach to double bass playing than Müller, the latter of whom speaks more about the value of strength and dependability in players.

Roughly two thirds of the content of Müller's "On the double bass and its use" covers playing Beethoven's symphonies. Müller systematically discusses each symphony, and includes both general advice and instructions for specific excerpts from each of the nine symphonies. Although Müller calls Beethoven's symphonies a "true treasure for the development of double bassists," he also criticizes the composer for overestimating human strength and not always considering the range and mechanics of the instrument, as evidenced by passages in Beethoven's symphonies that are too low or excessively difficult.lxv He claims that to be able to perform the Ninth Symphony, a double bassist must have the strength of Polyphemus and the technical abilities of Paganini.lxvi

In many places, Müller advises either transposing complete or partial passages up one octave so that they sound in the same octave as the cellos, or simplifying fast passages by playing longer note values and leaving the shorter notes in between to the cellos. According to Müller, these changes are necessary either to compensate for composers' disregard for the double bass's playing range, or for the sake of clarity. His remaining instructions include fingering and bowing recommendations and other practical advice. Müller also lists four main principles for successfully performing Beethoven's symphonies:

Franke is less readily willing than Müller to depart from what the composer has written. He acknowledges that many composers do not heed the double bass's playing range, but he opposes transposing for any other reason or simplifying fast passages. These changes are not up to the performer, he writes, but rather to the conductor, who is solely responsible for the intentions of the composer.lxviii As an example, Franke refers to Müller's modifications of two excerpts from Beethoven's Fifth Symphony.

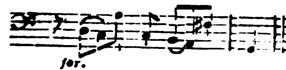

Müller transposes the motive that occurs in mm. 44 - 45 of the fourth movement of Beethoven's Fifth Symphony up one octave, and instructs that the high A should be executed as a harmonic on the D string, which allows the entire passage to be played with only one shift between the fourth and fifth notes (see figure 3). Müller states that since this motive is played only by the bass instruments, it should be heard very clearly, and that the low notes and quick string crossings required to execute the passage in its original form make it unclear.lxix

Figure 3. Müller's modification of Beethoven, Symphony no. 5, movt. 4, mm. 44 - 45.lxx

| Beethoven's version: | Müller's modification: |

|

|

Müller claims that the passage occurring in mm. 80 - 90 of the same movement should be reduced in order to conserve energy (see figure 4), but Franke opposes the simplification and states that the several indiscriminate changes that Müller suggests cannot be allowed.lxxi This disagreement again demonstrates the difference between the two players' concepts of double bass playing: Müller is concerned with stamina and having enough strength for a solid performance, and will cut out notes to achieve this end; while Franke adheres more closely to the prescribed notes, and is more optimistic about double bassists' stamina and technical abilities. Unfortunately, one can only speculate about whether Franke and others who followed his line of thought were successful in faithfully performing the written parts as powerfully as Müller and his fellow simplifiers.

Figure 4. Müller's reduction of Beethoven, Symphony no. 5, movt. 4, mm. 80 - 90.lxxii

Beethoven's version (mm. 80 - 85):

Müller's reduction (mm. 80 - 90):

Some of Franke's objections stem from the two bassists' contradicting ideas about fingering. In general, Müller's fingerings require more shifting and avoid open strings whenever possible, while Franke's fingerings utilize open strings in order to avoid shifting. An example of their differing preferences can be seen in mm. 16 - 17 of the first movement of the Second Symphony (see figure 5). Müller permits the open D in order to facilitate the required crescendo, but then continues up the D string with a closed G.lxxiii Franke however suggests playing the entire passage in one position with the G and A-flat on the G string, though he also instructs that the open strings be played with the proper tone color.lxxiv

Figure 5. Fingerings for Beethoven, Symphony no. 3, movt. 1, mm. 16 - 17.lxxv

Franke seems to misinterpret some of Müller's fingering suggestions, for he claims that Müller at times indicates reaching a minor third in one position: a span that is possible using Franke's system, but not Müller's. In each case however, the fingerings that Müller writes can in fact be executed using his own 3-finger system. The three examples that Franke sets forth are from the first movement of the Third Symphony, the third movement of the Fourth Symphony, and the fourth movement of the Sixth Symphony.

Franke apparently assumes that the minor thirds in these examples are intended to be executed without shifting, which he supports by quoting Müller's statement, "This shift, because it generates clumsy playing, is always reprehensible!"lxxvi However, referring to the quote in its original context in Müller's article reveals that Franke has misinterpreted Müller's words. Müller is not referring to shifting in general here, but rather specifically to shifting from one note to another with the fourth finger. That being the case, shifting from first finger on E-flat to fourth finger on G-flat, as Müller indicates for mm. 346 - 347 of the first movement of the Third Symphony, would be perfectly acceptable (see figure 6).

Figure 6. Müller's fingering for Beethoven, Symphony no. 3, movt. 1, mm. 346 - 347.lxxvii

Franke's next example, mm. 6 - 9 of the third movement of the Fourth Symphony, also suffers from missing information. The example shown comes from Müller's article (see figure 7), while Franke's version does not contain Müller's fingerings or string indications, and is truncated to the first beat of m. 8. Franke therefore only shows the descending minor thirds of G-flat to E-flat and C to A, which he hopes to convince readers should be played in a single 4-finger position, while in fact Müller clearly indicates that a great deal of shifting is necessary. According to Müller, the first four notes spanning a major sixth are all to be played on the D string, which requires shifting between each note; and the last four notes are to be executed in two positions on the A string. As Müller explains, one would have to shift numerous times anyway, and this rather unorthodox fingering at least helps one to achieve an even tone and calm bow because it avoids too many string crossings.lxxviii

Figure 7. Müller's fingering for Beethoven, Symphony no. 4, movt. 3, mm. 6 - 9.lxxix

In reference to the excerpt that begins in m. 64 of the fourth movement of the Sixth Symphony, Franke adds that he does not know of a rule that allows for the second finger to play the C-sharp, and that the third finger should be used instead (see figure 8).lxxx While the third finger would be logical for someone using all four fingers, in the 3-finger system one would most likely shift from first finger B to second finger C-sharp so that the D could then be played with the fourth finger, thereby avoiding the 'reprehensible' fourth-to-fourth finger shift from C-sharp to D.

Figure 8. Müller's fingering for Beethoven, Symphony no. 6, movt. 4, m. 64.lxxxi

While Franke does not comment on Müller's other suggested simplifications, two excerpts from the Sixth Symphony do prompt additional consideration. First, in the fourth movement Müller reduces the recurring figure that first appears in mm. 21 from sixteenth notes to eighth notes (see figure 9). He suggests that the double basses only play the notes that outline the harmony — while the cellos play the full motive — because continuously playing such loud and fast notes would result in a mess.lxxxii A common opinion among modern bassists, however, is that this particular passage is actually allowed, or even intended, to be somewhat 'messy' to create an effect. This movement of the symphony is titled "thunderstorm," and the fast, loud, low, and slurred notes played by the cellos and basses in this passage are thought to depict thunder. Müller's reduction makes the figure easier to perform, but it may also reduce the passage's resemblance to rumbling thunder. Nevertheless, a programmatic work can suggest an idea without exactly imitating its sound; Beethoven himself described his symphony as "more sentiment than tone painting," perhaps indicating that performers should aim to evoke the emotions associated with experiencing a thunderstorm rather than attempt to imitate its sound.lxxxiii

Figure 9. Müller's reduction of Beethoven, Symphony no. 6, movt. 4, mm. 21 - 22. Müller notates Beethoven's version with stems pointing up, and his own suggested modification with stems pointing down.lxxxiv

Müller's suggested modification of mm. 43 - 50 of theSixth Symphony is unique in that he suggests changes to a section in which Beethoven has already given the cellos and double basses independent parts (see figure 10). Müller reasons that transposing the lower notes up an octave improves clarity in the passage, and he confidently proclaims that Beethoven himself would approve of this change.lxxxv However, there are some indications that Beethoven had a very specific double bass part in mind in this section, and that the composer was perhaps even trying to avoid the modifications that Müller suggests.lxxxvi It was common practice in Beethoven's time — when a single part was usually written for the cellos and double basses — for double bassists to transpose any notes that fell below the range of their instrument (in Müller's case, a notated E). The transposition was generally applied to a whole passage in order to preserve its contour: in other words, to avoid breaking up the musical line.lxxxvii According to this rule, it would be logical to transpose the entire motive in question as Müller does, in order to maintain the same contour in both the double bass and cello parts. In this case however, Beethoven writes the passage so that the double basses enter an octave below the cellos, and then he breaks the double bass line so that only the last two sixteenth notes of the motive are played in unison with the cellos. If Beethoven expected double bassists to be inclined to transpose the motive from the beginning, he may have created a separate double bass part to indicate that the double basses should not follow common performance practices in this instance.

Figure 10. Müller's modification of Beethoven, Symphony no. 6, movt. 5, mm. 43 - 48.lxxxviii

Original:

Müller's suggestion:

As highlighted by the example above, the matter of when and how to modify double bass parts in nineteenth-century orchestral works is complex. Beethoven's symphonies are among the earliest orchestral works to include sections with independent double bass parts, and early-nineteenth century double bassists would have seen these parts as unique. Criticisms of 'simplifiers' suggest that nineteenth-century composers may have started writing separate double bass parts as an attempt to discourage undesirable modifications.lxxxix Even with independent parts, some double bassists who were used to simplifying their parts would likely have continued the practice out of habit. It appears that Müller was one of those performers who adhered to the old tradition, while Franke was more inclined to follow the developing trends in compositional and performance practices.

Müller's and Franke's articles reveal a great deal, not only about double bass playing in the mid-nineteenth century, but also about the two musicians themselves. Although little information is available about Franke's level of prestige or influence during his lifetime, his method and the two articles he authored in NZfM demonstrate that he was an experienced double bassist and active as an advocate of this somewhat neglected instrument. Franke's guidelines reflect a very idealistic view of double bass playing: he based his fingering system on convenience for the instrument's tuning and he believed that double bassists can use all four fingers just as the other string players do; he maintained that double bassists must play their part as it was written, unless the notes fall below the instrument's range; and rather than deny smaller people the opportunity to play double bass, he described a different way for them to hold the instrument.

While available documentation seems to suggest that Müller was better known than Franke, the former was more cautious in promoting his instrument's technical potential. Müller insisted that the human hand is only capable of reaching two semitones in one position; he advised the simplification of bass parts that he felt were too difficult to execute well; and he warned smaller people to stay away from the double bass and choose another instrument. Müller was also somewhat fixated on the physically arduous nature of the instrument. His articles on playing Beethoven's symphonies repeatedly warned players to conserve their strength, and the issue is central to an additional article he wrote for the NZfM years later.xc Müller was even praised for his secure and not overly technical approach to playing by composer Hector Berlioz, who wrote, "Without trying, as he easily might, to execute turns and trills of needless difficulty and grotesque effect, he makes this enormous instrument sing out broadly and grandly, drawing forth tones of the greatest beauty, which he shades with much art and feeling."xci

In context of the development of double bass playing, it is understandable that Müller's simple yet solid playing was more popular than Franke's more complex and demanding method during their time. As a result of double bassists not being particularly respected, the instrument's technical capabilities were generally still quite basic, and apparently lagged behind those of other instruments. Therefore, many double bassists may have lacked the dexterity to implement Franke's fingering system or to execute difficult passagework in its original form. Rather than striving for and falling short of the seemingly unattainable ideal of technical mastery, many conductors, teachers and performers concentrated on the double bass's role of setting the harmonic foundation in orchestral music. This more conservative approach would have afforded a greater rate of success for musicians of average professional aptitude who were engaged as the double bassists in many orchestras.

A number of double bassists who lived in the nineteenth century transcended the technical difficulties of their instrument and earned renown for their talents. The most famous examples are of course Domenico Dragonetti (1763-1846) and Giovanni Bottesini (1821-1889), whose performances and compositions for double bass demonstrated the instrument's virtuosic capabilities. Though much of Franke's life remains a mystery, his method and articles suggest that he at least recognized a higher technical potential in the double bass than many musicians of his time. In his method book Franke claims that he "grew up behind the double bass," and he may indeed have achieved a much higher technical level than most double bassists as a result of spending his entire life devoted to the instrument.xcii It is feasible that, as a true master of the instrument, he could both employ a 4-finger system that most other double bassists would find too physically exhausting, and precisely and clearly execute fast passage work in the orchestral repertoire that many other performers would need to simplify. The only other possible explanation for his writings could be that he was tenaciously idealistic about the possibilities of the double bass and perhaps a bit delusional about his own abilities. The more likely scenario though, is that he was a lesser-known talent in his day who has now all but been forgotten. Fortunately, his efforts to promote and defend his method in the NZfM have preserved his legacy, allowing later generations of double bassists to reevaluate his ideas, many of which it seems were not widely accepted during his lifetime.

The depth of Franke and Müller's discussion brings up issues of fingering choices that are relevant to modern performers of all styles. The methods that many bass players use today were either written in the late nineteenth century (much closer to Franke and Müller's time than the present day), or are directly based on those methods.xciii In this period, instruments were still set up with gut or sometimes silk strings, which played quite differently than modern strings made primarily of metal. This calls into question how Simandl's fingering system is still the prevailing standard in double bass technique after 140 years of technical development and the eventual transition to steel strings. Fisticuff technique, in essence a 2-finger system with even less possibility for dexterity, died out as strings developed and instruments became more playable. As such, a reconsideration of fingerings would be expected to occur alongside the further evolution of string technology. Instead, the 3-finger 'Simandl' system remains widely accepted as standard, while deviations from this system are now generally viewed as advanced or non-traditional techniques.

Müller and Franke's written discourse about the double bass, which appeared in the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik between 1849 - 1851, provides a uniquely in-depth source on the values and circumstances that influenced double bass playing in the mid-nineteenth century. Modern 'HIP' performers can use these articles to explore how historical techniques can be used to enhance historically informed performance, especially in regard to the practice of simplifying double bass parts in orchestral music. These and other early sources also highlight the wide variety of fingering systems that existed before Simandl technique became the predominant standard as it remains today. Modern performers of all styles should question why fingering technique did not keep evolving alongside string technology, and are encouraged to explore the advantages and disadvantages of Franke's 4-finger system in conjunction with other fingering techniques. Additionally, while Franke's ideas have been briefly referenced in modern artistic research, newly rediscovered information about his career grants him a rightful place on the list of important historical double bassists.

Although Müller and Franke discuss their own performance values and playing methods in great detail, they are just two of many perspectives of historical double bass performance practices. Although I chose to focus on how their ideas compared to each other, there is even more to be learned from examining their methods relative to sources from other regions and periods. As primarily orchestral double bassists, Müller and Franke do not delve into the subject of melodic or solo playing, and thus omit topics that would be hard to avoid in a method for solo playing, but that are perhaps less essential to the double bass's orchestral role: topics including thumb position, alternative tunings, and stylistic elements such as vibrato, portamento, and rubato are not discussed by either author, and therefore need to be explored through other sources. The practice of modifying double bass parts also warrants further examination, as the process certainly evolved throughout history as scoring became more specific. Double bassists performing baroque basso continuo parts, those performing Classical symphonies with a single part for the cellos and double basses, and those performing an independent double bass part in Romantic or later works, all faced different expectations from composers, conductors and performing colleagues regarding their degree of faithfulness in executing their parts as written.

One of the unexpected results of this research is an increased awareness of individual performers' personalities and their role in the development of double bass performance practices throughout music history. Müller's and Franke's writings are an ideal reference for this topic not only because they demonstrate pronounced differences in opinion between two musicians who were active in the same period and working in reasonable proximity to one another, but also because they happened to be some of the last sources published prior to the ever popular Simandl method, which in a way marks the beginning of modern double bass playing. Motivated by a century of developing albeit insufficient methods, yet still free from the influence of widely standardized technique, Müller and Franke represent a critical point in the double bass's pedagogical history.

Franke, F.C. Anleitung den Contrabass zu spielen. Chemnitz: J.G. Häcker, 1845. Accessed August 1, 2014. http://www.mdz-nbn-resolving.de/urn/resolver.pl?urn=urn:nbn:de:bvb:12-bsb10497336-0.

Müller, August. "Tabletten eines Contrabassisten." Neue Zeitschrift für Musik 27, no. 52 (December 25, 1847): 309-310. Accessed August 13, 2014. https://archive.org/details/NeueZeitschriftFuerMusik1847Jg14Bd27.

Müller, August. "Ueber den Contrabaß und dessen Behandlung, mit Hinblick auf die Symphonien von Beethoven." Neue Zeitschrift für Musik 28, no. 45 (June 3, 1848): 265-267. Accessed July 15, 2014. https://archive.org/details/NeueZeitschriftFuerMusik1848Jg15Bd28.

Müller, August. "Ueber den Contrabaß und dessen Behandlung, mit Hinblick auf die Symphonien von Beethoven. (Zweiter Artikel)" Neue Zeitschrift für Musik 29, no. 29 (October 7, 1848): 161-166. Accessed July 15, 2014. https://archive.org/details/NeueZeitschriftFuerMusik1848Jg15Bd29.

"Anfrage" Neue Zeitschrift für Musik 29, no. 30 (October 10, 1848): 179. Accessed July 15, 2014. https://archive.org/details/NeueZeitschriftFuerMusik1848Jg15Bd29.

Müller, August. "Erwiderung." Neue Zeitschrift für Musik 29, no. 38 (November 7, 1848): 224. Accessed July 15, 2014. https://archive.org/details/NeueZeitschriftFuerMusik1848Jg15Bd29.

Franke, F.C. "Bemerkungen zu dem Aufsatze in dies. Zeitschr., Band 28. Nr. 45: Ueber den Contrabaß und dessen Behandlung, mit Hinblick auf die Symphonien von Beethoven, von Aug. Müller, und dessen zweiten Artikel, Band 29. Nr. 29." Neue Zeitschrift für Musik 29, no. 47 (December 9, 1848): 272-275. Accessed July 15, 2014. https://archive.org/details/NeueZeitschriftFuerMusik1848Jg15Bd29.

Müller, August. "Ueber den Contrabaß und dessen Behandlung, nebst einem Hinblick auf die Symphonieen von Beethoven. (Dritter Artikel und Schluß)" Neue Zeitschrift für Musik 30, no. 2 (January 4, 1849): 9-11. Accessed July 15, 2014. https://archive.org/details/NeueZeitschriftFuerMusik1849Jg16Bd30.

Müller, August. "Ueber den Contrabaß und dessen Behandlung, nebst einem Hinblick auf die Symphonieen von Beethoven. (Fortsetzung)" Neue Zeitschrift für Musik 30, no. 3 (January 8, 1849): 15-18. Accessed July 15, 2014. https://archive.org/details/NeueZeitschriftFuerMusik1849Jg16Bd30.

Müller, August. "Ueber den Contrabaß und dessen Behandlung, nebst einem Hinblick auf die Symphonieen von Beethoven. (Fortsetzung)" Neue Zeitschrift für Musik 30, no. 5 (January 15, 1849): 28-32. Accessed July 15, 2014. https://archive.org/details/NeueZeitschriftFuerMusik1849Jg16Bd30.

Müller, August. "Ueber den Contrabaß und dessen Behandlung, nebst einem Hinblick auf die Symphonieen von Beethoven. (Fortsetzung)" Neue Zeitschrift für Musik 30, no. 13 (February 12, 1849): 65-67. Accessed July 15, 2014. https://archive.org/details/NeueZeitschriftFuerMusik1849Jg16Bd30.

Müller, August. "Ueber den Contrabaß und dessen Behandlung, nebst einem Hinblick auf die Symphonieen von Beethoven. (Fortsetzung)" Neue Zeitschrift für Musik 30, no. 15 (February 19, 1849): 82-83. Accessed July 15, 2014. https://archive.org/details/NeueZeitschriftFuerMusik1849Jg16Bd30.

Müller, August. "Ueber den Contrabaß und dessen Behandlung, nebst einem Hinblick auf die Symphonieen von Beethoven. (Schluß)" Neue Zeitschrift für Musik 30, no. 21 (March 12, 1849): 109-113. Accessed July 15, 2014. https://archive.org/details/NeueZeitschriftFuerMusik1849Jg16Bd30.

Müller, August "F. C. Franke's Anleitung den Contrabass zu spielen." Neue Zeitschrift für Musik 30, no. 45 (June 4, 1849): 243-246. Accessed July 15, 2014. https://archive.org/details/NeueZeitschriftFuerMusik1849Jg16Bd30.

Müller, August. "Ueber das Wirken des Musikers im Orchester." Neue Zeitschrift für Musik 31, no. 41 (November 18, 1849): 217-219. Accessed August 13, 2014. https://archive.org/details/NeueZeitschriftFuerMusik1849Jg16Bd31.

Müller, August. "Ueber das Wirken des Musikers im Orchester. (Schluß)" Neue Zeitschrift für Musik 31, no. 43 (November 25, 1849): 229-230. Accessed August 13, 2014. https://archive.org/details/NeueZeitschriftFuerMusik1849Jg16Bd31.

Franke, F.C. "Ueber den Contrabaß." Neue Zeitschrift für Musik 34, no. 3 (January 17, 1851): 29-32. Accessed August 1, 2014. https://archive.org/details/NeueZeitschriftFuerMusik1851Jg18Bd34.

Müller, August. "Der Contrabassist als Arbeiter." Neue Zeitschrift für Musik 57, no. 25 (December 19, 1862): 225-226. Accessed August 13, 2014. https://archive.org/details/NeueZeitschriftFuerMusik1862Jg29Bd57.

Müller, August. "Ein guter Contrabaß." Neue Zeitschrift für Musik 60, no. 13 (March 25, 1864): 108. Accessed August 13, 2014. https://archive.org/details/NeueZeitschriftFuerMusik1864Jg31Bd60.

Asioli, Bonifazio. Elementos para el Contrabajo, con un nuevo modo de hacer uso de los dedos. Translated into Spanish by Mariano Herrero y Sessé. Manuscript. Milan: c.1873. Accessed November 24, 2014. http://bdh.bne.es/bnesearch/detalle/bdh0000158396.

Bach, Johann Sebastian. St. Matthew Passion. Edited by Alfred Dürr. Urtext Study Score. Kassel: Bärenreiter, 1974.

Beethoven, Ludwig van. Beethoven, the Man and the Artist as Revealed in his own Words. Edited by Friedrich Kerst and Henry Edward Krehbiel. Project Gutenberg, 2002. Accessed December 6, 2014. http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/3528.

Beethoven, Ludwig van. Symphony No. 6. Manuscript. From International Music Score Library Project, Petrucci Music Library. Accessed September 15, 2014. http://imslp.org/wiki/Special:ReverseLookup/46098

Berlioz, Hector. Autobiography of Hector Berlioz, member of the Institute of France, from 1803 to 1865. Comprising his travels in Italy, Germany, Russia, and England. Volume 2. Translated by Rachel Holmes and Eleanor Holmes. London: Macmillan & co., 1884). Accessed August 25, 2014. http://www.archive.org/details/autobiographyof02berl.

Bottesini, Giovanni. Grande Méthode Complète de Contrebasse. Paris: Escudier, c. 1869. Accessed July 1, 2014. http://imslp.org/wiki/Special:ReverseLookup/254239

Brun, Paul. A New History of the Double Bass. Villeneuve d'Ascq: Paul Brun Productions, 2000.

Corrette, Michel. Méthodes pour apprendre àjouer de la contrebasse à3, à4, et à5 cordes, de la quinte ou alto et de la viole d'Orphee: Réimpression de l'édition Paris, 1781. Geneva: Minkoff Reprint, 1977.

Dalla Torre, Silvio. BASSics: Basics of the Four-Finger-Technique for Playing the Double Bass According to the "New Dutch School." Rostock: Sidatoverlag, 2004.

Dalla Torre, Silvio. "Two, Three, or Four Fingers." Accessed September 25, 2014. http://silviodallatorre.com/index.php?language=en&hauptrubrik=double-bass&ebene=2&thema=6.

Fröhlich, Franz Joseph. Vollständige Theoretisch-praktische Musikschule. Bonn: N. Simrock, 1811. Accessed July 1, 2014. http://reader.digitale-sammlungen.de/resolve/display/bsb10527195.html.

Hause, Wenzeslas. Méthode Complette de Contrebasse. Mainz: Schott, 1826.

Hofmeister XIX. Accessed January 17, 2015. http://hofmeister.rhul.ac.uk.

Ledebur, Carl Freiherrn von. Tonkünstler-Lexicon Berlin's: von den ältesten Zeiten bis auf die Gegenwart. Berlin: Ludwig Rauh, 1861. Accessed January 1, 2015. https://archive.org/details/tonknstlerlexi00lede.

Miné, Jacques Claude Adolphe. Methode de Contre-Basse. Paris: A. Meissonier, c. 1830. Accessed July 1, 2014. http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b52501989f.

Petracchi, Franceso. Simplified Higher Technique. London: Yorke Edition, 1982.

Pinca, Massimo. "August Müller's Contributions to the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik (1848-1849): Evidence of Approaches to Orchestral Double Bass Playing in the mid-19th Century." Ad Parnassum, A Journal of Eighteenth- and Nineteenth-Century Instrumental Music 12, no. 23 (April 2014): 15-59.

Rabbath, François. Art of the Left Hand. Directed by Hans Sturm. Muncie, IN: Ball State University/Avant Bass, 2010. DVD.

Rabbath, François. Nouvelle Technique de la Contrabasse. Vol. 3. Paris: Alphonse Leduc, 1984.

Review of "F. C. Franke, Anleitung den Contrabass zu spielen." Neue Zeitschrift für Musik 22, no. 43 (May 28, 1845): 177. Accessed July 15, 2014. https://archive.org/details/NeueZeitschriftFuerMusik1845Jg12Bd22.

Simandl, Franz. New Method for the Double Bass. New York: Carl Fischer, 1904. Accessed July 1, 2014. http://imslp.org/wiki/Special:ReverseLookup/272043

Quantz, Johann Joachim. "Chapter 17, Section 5: Of the Double Bass Player in Particular." In On Playing the Flute. 2nd ed. Translated by Edward R. Reilly. London: Faber & Faber, 1985.

Unless otherwise noted, foreign language texts that are quoted or paraphrased in this paper have been translated into English by the author. See appendix for original text and translations.

i Silvio Dalla Torre, "Two, Three, or Four Fingers," http://silviodallatorre.com/index.php?language=en&hauptrubrik=double-bass&ebene=2&thema=6. Dalla Torre's article seems to be the only source that gives the full name Friedrich Christoph Franke. Franke is listed as "F. Christoph Francke" in Carl Freiherrn von Ledebur, Tonkünstler-Lexicon Berlin's: von den ältesten Zeiten bis auf die Gegenwart (Berlin: Ludwig Rauh, 1861), 161, https://archive.org/details/tonknstlerlexi00lede; All other sources, including Franke's own publications, include only the initials F.C.

ii See bibliography for chronological listing of Franke's and Müller's publications.

iii Massimo Pinca, "August Müller's Contributions to the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik (1848-1849): Evidence of Approaches to Orchestral Double Bass Playing in the mid-19th Century," Ad Parnassum, A Journal of Eighteenth- and Nineteenth-Century Instrumental Music 12, no. 23 (April 2014): 17-19.

iv German title: "Ueber den Contrabaß und dessen Behandlung, mit Hinblick auf die Symphonien von Beethoven." Divided across eight issues of the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik : vol. 28, no. 45 (June 3, 1848); vol. 29, no. 29 (October 7, 1848); vol. 30, no. 2 (January 4, 1849), no. 3 (January 8, 1849), no. 5 (January 15, 1849), no. 13 (February 12, 1849), no. 15 (February 19, 1849), no. 21 (March 12, 1849).

v August Müller, "Ueber den Contrabaß und dessen Behandlung, mit Hinblick auf die Symphonien von Beethoven," Neue Zeitschrift für Musik 28, no. 45 (June 3, 1848): 267, https://archive.org/details/NeueZeitschriftFuerMusik1848Jg15Bd28.

vi Ledebur, 161.

vii Franke signs off his 1851 article with, "F.C. Franke, herz. Dessauischer Kammermusikus." F.C. Franke "Ueber den Contrabaß," Neue Zeitschrift für Musik 34, no. 3 (January 17, 1851): 32, https://archive.org/details/NeueZeitschriftFuerMusik1851Jg18Bd34.

viii Hofmeister XIX, http://hofmeister.rhul.ac.uk: March 1845 (p. 34) & February 1874 (p. 19).

ix "Anfrage," Neue Zeitschrift für Musik 29, no. 30 (October 10, 1848): 179, https://archive.org/details/NeueZeitschriftFuerMusik1848Jg15Bd29.

x For a representative sampling, see Michel Corrette, Méthodes pour apprendre àjouer de la contrebasse à3, à4, et à5 cordes, de la quinte ou alto et de la viole d'Orphee: Réimpression de l'édition Paris, 1781 (Geneva: Minkoff Reprint, 1977); Franz Joseph Fröhlich, Vollständige Theoretisch-praktische Musikschule (Bonn: N. Simrock, 1811), http://reader.digitale-sammlungen.de/resolve/display/bsb10527195.html; Wenzeslas Hause, Méthode Complette de Contrebasse (Mainz: Schott, 1826); Jacques Claude Adolphe Miné, Methode de Contre-Basse (Paris: A. Meissonier, c.1830), http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b52501989f; Johann Joachim Quantz, "Chapter 17, Section 5: Of the Double Bass Player in Particular," in On Playing the Flute. 2nd ed. trans., Edward R. Reilly. London: Faber & Faber, 1985.

xi F.C. Franke, Anleitung den Contrabass zu spielen (Chemnitz: J.G. Häcker, 1845), 2, http://www.mdz-nbn-resolving.de/urn/resolver.pl?urn=urn:nbn:de:bvb:12-bsb10497336-0.

"Bass nennt man in Allgemeinen bei jedem Musikstücke die tiefsten Töne, gleichviel, ob sie gesungen, oder auf irgend einem Instrumente hervorgebracht werden; durch sie bestimmt der Componist die Harmonie Folge, den eigentlichen, innern Werth der Musik. Es ist dem [zu] folge eine gute Besetzung des Basses hauptsächlich erforderlich, der Ausführung eines Tonstücks den vollendeten Eindruck zu sichern. Wie [nun] einem Orgelwerke ein kräftiges Pedal zur Erhebung dient und demselben Fülle und Majestät giebt, so bewirkt dies bei einem Orchester ein gut besetzter Bass, dessen Basis immer der Contraviolon bleiben wird, da unter allen musikalischen Instrumenten keines ist, welches bei solcher Tiefe, durch die Menge der verschiedenartigsen Töne, solche Würde behauptet, während er den übrigen Instrumenten in allen Nüancirungen gleich kommt."

xii Müller, "Ueber den Contrabaß" (June 3, 1848): 265.

"Diese mangelhafte Seite so mancher Kunstproductionen wird gewiß Jedermann bedauern, der Urtheil hat, und wird mit meiner Behauptung übereinstimmen, daß diejenigen Ausführungen von Orchesterwerken, wobei die Bässe im Ensemble nur mangelhast gehört werden, sehr unvollkommen genannt werden müssen."

xiii Fröhlich, 92.

"Contrebassist, so zu sagen, die Seele der ganzen Musik sey."

xiv Quantz (trans. Reilly), 246-247.

xv Miné, 1.

"La contre-basse est l'instrument le plus grâve de l'orchestre; sa puissance de son le rend indispensable pour nourir et lier les masses d'harmonie qui se trouvent dans la musique en simphonie."

xvi Franke, Anleitung, 1.

"Wie sehr auch die Wichtigkeit des Contraviolon bei jeden Orchester hervortritt, so findet man doch nur wenig Contrabassspieler welche dieses Instrument gut zu behandeln verstehen";

Müller, "Ueber den Contrabaß" (June 3, 1848): 265.

"Der Contrabaß, dieses wichtige Orchester-Instrument, blieb bis jetzt im Allgemeinen hinsichtlich seiner Ausbildung in auffallendem Verhältnisse gegen alle andere Musik-Instrumente zurück."

xvii Franke, Anleitung, 1.

"Ausser den sonst erforderlichen Fähigkeiten gehört allerdings starke Muskelkraft, viele Ausdauer und bedeutende körperliche Anstrengung dazu wenn jemand auf diesem kolossalen Instrumente irgend Fortschritte machen will, allein wer den Parnass erklimmen will, darf sich keine Mühe verdriessen lassen."

xviii Müller, "Ueber den Contrabaß" (June 3, 1848): 266.

"wird der Contrabaß gar oft von Subjecten behandelt, welchen bei allem Eifer die nöthige körperliche Kraft und Größe fehlt. . . . Ein David kann diesen Goliath nicht bezwingen!"

xix Franke, Anleitung, 1.

"Erscheint nämlich dessen Stellnug hier nach nur als eine sehr untergeordnete, so kann sie auch der Natur der Sache nach den Kunstjünger nicht eben zu dem an sich höchst trocknen und angreifenden Stadium des Contrabassspieles aufmuntern."

xx Müller, "Ueber den Contrabaß" (June 3, 1848): 265-266.

"betrachtet man meistens den Contrabaß als ein Instrument, welches nicht genug Interesse bietet, um seine Ausbildung zum Lebenszwecke zu machen. . . . er steht oft, sehr oft verlassen und verkannt, und geräth leider meistens in die Hände von Ignoranten"

xxi Ibid., 266.

"Es existiren genug Institute, bei welchen die Contrabassisten sich erst im Mannesalter diesem Instrumente gewidmet haben: was kann man daher von ihnen erwarten?"

xii Ibid.

"der Grund, daß dem Contrabasse die verhältnißmäßig gleiche Ausbildung wie den andern Instrumenten noch nicht geworden ist, auch darin, daß man weder ganz zweckmäßige Schulen hat, noch wirklich gebildete Lehrer in diesem Fache zu gewinnen sucht, welche ihre Zöglinge auf den rechten Weg bringen und sie darauf erhalten. . . . Die Directoren und Vorsicher von Etablissements, welche die Ausbildung der praktischen Musik zum Zwecke haben, sind viel zu nächlässig darin, und nehmen selbst viel zu wenig Interesse an dem Contrabaß."

xiii Ibid.

"Man behilft sich wie es eben geht, und so wird denn der alte Sauerteig seit langer Zeit, von Generation zu Generation, bewahrt und geknetet."

xxiv Franke, Anleitung, 1.

"Ein Hauptgrund weshalb es verhältnissmässig so wenig tüchtige Contrabassisten giebt, liegt aber auch darin, dass für diese Instrument noch zu wenig wirklich practische, auf Erfahrung gegründete Schulen erschienen sind, die bereits vorhandenen aber theils ihrem Zwecke nicht genug entsprechen, theils nicht hinlänglich bekannt und verbreitet sind. . . . Dies und die mir von verschiedenen Seiten gewordene Ausforderung veranlassten mich, das nachstehende Werkschen den bereits vorhandenen Schulen anzureihen";

F.C. Franke, "Bemerkungen zu dem Aufsatze in dies. Zeitschr., Band 28. Nr. 45: Ueber den Contrabaß und dessen Behandlung, mit Hinblick auf die Symphonien von Beethoven, von Aug. Müller, und dessen zweiten Artikel, Band 29. Nr. 29" Neue Zeitschrift für Musik 29, no. 47 (December 9, 1848): 275, https://archive.org/details/NeueZeitschriftFuerMusik1848Jg15Bd29.

"Bei der Aufzählung sämmtlicher herausgekommenen Lehrbücher und Schulen ist unbegreiflicher Weise gerade das neueste (schon oben citirte) kleine Werk: Anleitung den Contrabaß zu spielen, Chemnitz, bei J. G. Häcker, obschon in Nr. 43. dies. Zeitschr., Bd. 22 vom J. 1845 eine anerkennende Recension darüber erschienen, gar nicht in Erwähnung gebracht. . . . jedenfalls aber dient es zum vollständigen Beweise, daß die geringe Anzahl der hierher gehörenden vorhandenen Werke nicht hinlänglich bekannt und verbreitet ist."

xxv Franke, Anleitung, 1.

"gute Contrabassisten su selten sind auch darin dass bei der Wahl des Contrabasspielers für ein Orchester aus mancherlei, namentlich aber aus öconomischen Rücksichten nicht immer mit der nöthigen Umsicht zu Werke gegangen wird."

xxvi Müller, "Ueber den Contrabaß" (June 3, 1848): 267.

"Warum setzt man nicht einen Preis für eine gute Contrabaßschule aus? . . . Welcher Musikalien-Verleger wird einen Künstler für eine Contrabaßschule anständig honoriren? — Ja man muß fürchten, daß die meisten Herren eine Schule für den Contrabaß gar nicht, am Ende nicht einmal gratis übernehmen würden."

xxvii Fröhlich, 92.

"Wir können nicht umhin, die verderbliche Gewohnheit bei vielen Orchestern zu rügen, wo man dieses Instrument Personen anvertraut, die, wenn sie auch einige Fertigkeit im Mechanischen derselben sich erworben haben, weit entfernt, den tiefen Charakter zu ahnden, welcher in der von ihnen vorzutragenden Stimme liegt, theils mit Oberflächlichkeit die würdigsten kräftigen Stellen, den reinen Ausfluss der höhern Begeisterung des Tonsetzers, mit kälte behandeln, theils die sanftesten zartesten Gegensätze mit einem unzeitigen geschmacklosen Feuer verderben."

xxviii Hause, "Vorrede," in Méthode Complette de Contrebasse (Mainz: Schott, 1826).

"Troz seiner Unentbehrlichkeit, giebt es doch sehr wenige die denselben gut zu behandeln wissen. Sollte die Ursache wohl darinnen zu suchen seyn, dass noch keine Anleitung zur zweckmaesigen Behandlung desselben vorhanden ist, daran doch jedes andere Instrument keinen Mangel hat?"

xxix Franke, Anleitung, 2.

"Die Grösse des Contraviolin ist sehr verschieden, man findet aber bei einem guten Instrumente stets ein richtiges Verhältniss der Form, Grösse und Stärke jedes einzelnen Theiles an sich selbst, wie zu dem ganzen Baue."

xxx August Müller, "Ueber den Contrabaß und dessen Behandlung, mit Hinblick auf die Symphonien von Beethoven. (Zweiter Artikel)" Neue Zeitschrift für Musik 29, no. 29 (October 7, 1848): 161-163, https://archive.org/details/NeueZeitschriftFuerMusik1848Jg15Bd29.

"Die Saiten müssen (neben dem, daß man sie hoch legt, um das Anschlagen auf das Griffbret zu vermeiden) auf dem Steg möglichst weit auseinander und so gelegt werden, daß man jede der beiden mittleren kräftig mit dem Bogen anstreichen kann, ohne dabei eine andere mit anzustreichen; . . . der benutze immer italienische Saiten, die ohne allen Zweifel den Vorzug vor allen deutschen und französischen verdienen. Wir haben das gute Material nicht wie die Italiener; auch sind unsere deutschen Saiten, so wie auch die französischen, wenn sie auf das Instrument gezogen sind, von einer unausstehlichen Härte und Starrheit. Die Ursache dieser letzten unangenehmen Eigenschaft ist, daß sie in viel längeren Wellen gedreht sind als die italienischen. . . . Was die Dicke der Saiten anbelangt, so muß sowohl die Größe als auch die Construction des Instruments den Maßstab geben . . . Zum Schluß noch die Bemerkung, daß nach meinen Erfahrung eine übersponnene A-Saite (welche im fertigen Zustande etwas dicker als die auf dem Instrumente befindliche G-Saite sein muß) der nicht übersponnene vorzuziehen ist, da letztere im Spiele genirt, weil sie viel dicker als die anderen Saiten sein muß, und auch bei weitem nicht den freien Ton wie die übersponnene hat."

xxxi Franke, Anleitung, 2;

"wenn der Kopf mit Blei ausgefüllt ist, so gewährt die dadurch hervorgebrachte Schwere manchen Vortheil";

August Müller, "F. C. Franke's Anleitung den Contrabass zu spielen," Neue Zeitschrift für Musik 30, no. 45 (June 4, 1849): 244, https://archive.org/details/NeueZeitschriftFuerMusik1849Jg16Bd30.

"Nur glaube ich nicht, daß es gut ist, den Kopf des Bogens mit Blei auszufüllen; er wird so zu schwer und hemmt die leichte, freie Bewegung";

Franke, "Ueber den Contrabaß," 29.

"Bei dem Bogen empfehle ich den Kopf mit Blei auszufüllen, und muß, obgleich Hr. M. Bd. 30, Nr. 45 dies nicht für gut hält, dabei verbleiben, denn: der Bogen ist ohne dies Hülfsmittel am Ende der Stange durch den Frosch ungleich schwerer als am Kopfende, so daß der Spieler die Hauptschwere desselben in der Hand hat und auf diese Weise die Töne nur durch Kraftaufwand hervorbringen kann, indeß der mit Blei ausgefüllte Kopf ein Gegengewicht giebt, welches die Kraft des Spielers wesentlich unterstützt, mithin Vortheile gewährt, die selbst der kräftigste Bassist nicht verschmähen wird."

xxxii Franke, "Bemerkungen": 273.

"die zum Contrabaßspiel erforderlichen materiellen Bedürfnisse (ein gutes Instrument, ein guter und hinsichtlich der Stärke im richtigen Verhältniß stehender Bezug, ein guter Bogen u.) nur äußerst selten für nothwendig erachtet werden. — Eine solche Stellung, in welcher die Erzeugnisse (die Töne) zwar überall, das Instrument selbst sammt seinen Spielern aber so selten gewürdigt weden, kann allerdings auch nicht geeignet sein, Kunstjünger anzuspornen, sich im vollen Sinne des Wortes dem Contrabasse zu widmen."

xxxiii August Müller, "Ein guter Contrabaß" Neue Zeitschrift für Musik 60, no. 13 (March 25, 1864): 108, https://archive.org/details/NeueZeitschriftFuerMusik1864Jg31Bd60.

"entweder produciren sie, wenn ihnen im forte von den Spielern tüchtig zugesetzt wird, einen harten, holzigen Ton ohne Nachklang, oder sie treten nicht genug hervor und verschwinden sogar nicht selten ganz in der Masse. Des auch zuweilen vorkommenden ganz und gar verwerflichen Aufschlagens der Saiten"

xxxiv Ibid.

"Die alten Contrabässe von bekannten italienischen Meistern sind selten, sogar sehr selten. . . . Ferner sind die meisten sehr dünn von Holz, und zwar von einem nichts weniger wie ausgesuchten Holze, sowol an Decke und Boden als auch an den Zargen. Auch fehlt es an passender Mensur, an richtigem Arrangement des Steges, des Griffsbretts etc. etc. Mit einem Worte: sie sind für ihren zu erfüllenden Zweck in hohem Grade unzureichend."

xxxv Franke, Anleitung, 3.

"Je grösser der Spieler ist, desto mehr Vortheile wird derselbe erlangen, wenn er den Contraviolon, welcher mit der linken Hand am Halse festgehalten wird, gerade vor sich hinstellt , so dass der linke Fuss, mitten hinter dem Instrumente stehend, seinen eignen Körper trägt, den rechten Fuss dagegen ein wenig vorwärts setzt und das etwas auswärts gebogene Knie an der Zarge und dem Rande des Bodens anlegt, um durch eine Bewegung desselben das Instrument vor- und rückwärts drehen zu können, wie es die Hervorbringung der Töne auf der tiefsten und auf der höchsten Saite erfordert. Beim Gebrauch der tiefsten Saiten kann man, indem man das Instrument vorwärts wendet, zugleich den eignen Körper ein wenig nach der rechten Seite biegen. Je kleiner der Spieler ist, desto vortheilhafter wird es, das Instrument mit der Large, wo die tiefste Saite liegt, mehr nach sich gewendet vor sich zu stellen, auf dem rechten Fusse, welcher dem Rande des Bodens gans nahe seinen Platz erhält, seinen eignen Körper ruhen zu lassen, und den linken fuss hinter dem Instrumente so zu setzen, dass das ein wenig vorwärts gebogene Knie den Boden berührt, und durch eine Bewegung die schon erwähnte Wendung des Instruments bewerkstelligt. Auch hierbei ist die Biegung des eignen Körper beim Gebrauch der tiefsten Saite nicht zu verwerfen, jedoch dürfen alle Bewegungen immer nur kann bemerkbar sein, wie überhaupt mit vieler Sorgfalt darauf zu achten, dass die Haltung stets gerade und ungezwungen, und jede unnöthige Bewegung zu vermeiden ist."

xxxvi August Müller, "Tabletten eines Contrabassisten," Neue Zeitschrift für Musik 27, no. 52 (December 25, 1847): 309, https://archive.org/details/NeueZeitschriftFuerMusik1847Jg14Bd27.

"Eine große Nothwendigkeit für das gute Spiel auf dem Contrabaß ist das Festhalten des Instruments mit der inneren Seite des linken Knies und des oberen Theils der rechten Wade, wobei die Spitze des rechten Fußes nach Außen gekehrt werden muß. . . . Der Violinspieler muß die Violone fest mit dem Kinn halten, will er ungenirt und frei wirken; so auch der Cellist, welcher sein Instrument fest zwischen den Beinen hält. . . . Die Arme, die Mittel zur Hervorbringung der Töne, müssen frei und ungezwungen wirken können"

xxvii Müller, "Ueber den Contrabaß" (October 7, 1848): 163.

"Der von mir schon empfohlene längere Fuß des Instruments wird deises Festhalten sehr unterstützen. . . . der Spieler muß besonders auf eine würdevolle Haltung bedacht sein, da er sein Instrument stehend behandelt und somit dem Auge des Beobachters mehr ausgesetzt ist."

xxxviii Müller, "F.C. Franke's Anleitung": 244.

"Bei der Stellung des Körpers empfiehlt Hr. Fr., den Körper etwas nach der rechten Seite zu biegen, wenn die tieferen Saiten angestrichen werden sollen. Ich finde dies eben so falsch als den Rath, daß der kleinere Spieler das Instrument mehr nach sich zuwenden soll und auf dem rechten Fuß seinen eigenen Körper ruhen zu lassen. Der Contrabassist muß, meiner Ansicht nach, stets gerade und aufrecht stehen und darf sich bei dem Gebrauch der tieferen Saiten nicht auf die rechte Seite neigen; das Gewicht des Spielers selbst aber muß immer auf den linken Fuß kommen. Stützt sich der Contrabassist auf die rechte Seite, dann verliert er an der freien Bewegung des rechten Armes. Das linke Knie wird die nöthige Wendung des Instruments schon bewerkstelligen, wenn die tieferen Saiten im Gebrauche sind. — Kleine Contrabassisten sollen auch kleinere Instrumente nehmen, oder noch besser von der großen Geige ganz wegbleiben."

xxxix Müller, "Ueber den Contrabaß" (October 7, 1848): 163.

"Der linken Hand des Contrabassisten darf nur (wie der des Cellisten) die einzige Function des Tönegreifens obliegen";

Franke, Anleitung, 3.

"Die Stellung wirkt hauptsächlich auf die Kraft und Gewandheit, es kann aber eine und dieselbe nicht Jedem die vortheilhafteste sein, weil dieselbe mehr von der Grösse des Spielers zu der des Instruments abhängt"

xl Bottesini used 1-4 fingerings for both half steps and whole steps, but employed 1-3-4 fingerings for consecutive half steps. For more on fingering systems, see Dalla Torre, "Two, Three, or Four Fingers," and/or Massimo Pinca, "August Müller's Contributions to the Neue Zeitschrift für Musik (1848-1849): Evidence of Approaches to Orchestral Double Bass Playing in the mid-19th Century." Ad Parnassum, A Journal of Eighteenth- and Nineteenth-Century Instrumental Music 12, no. 23 (April 2014): 38-40.

For specific examples mentioned, see Corrette, 6, 9; Miné, 3-9; Franke, Anleitung, 7-8; Hause, 3-4; Bonifazio Asioli, Elementos para el Contrabajo, con un nuevo modo de hacer uso de los dedos, trans. (Spanish) by Mariano Herrero y Sessé. manuscript (Milan, 1873?), http://bdh.bne.es/bnesearch/detalle/bdh0000158396; Franz Simandl, New Method for the Double Bass (New York: Carl Fischer, 1904), 8, http://imslp.org/wiki/Special:ReverseLookup/272043;Giovanni Bottesini, Grande Méthode Complète de Contrebasse. Paris: Escudier, c.1869. http://imslp.org/wiki/Special:ReverseLookup/254239, 27-28; Fröhlich, 98-103.

xli Brun, 83-89.

xlii Franke, "Ueber den Contrabaß": 30.

"kann nichts zweckmäßiger sein, als in der ersten Lage, ohne springen, oder rutschen zu müssen, alle Töne und dadurch die möglichst sichersten Regeln für jede vorkommende Passage zu erhalten" Franke, "Ueber den Contrabaß,"

xliii Franke, "Bemerkungen":274.

"Dieser Griff bedingt zwar in den tieferen Lagen eine Spannung der Finger, man hat dadurch aber den unberechenbaren Vortheil, ohne zu springen oder zu rutschen, auch in der tiefsten Lage alle Töne greifen zu können; . . . Ueberflüssiges Springen ist aber eben so verwerflich, als der Verf. ausdrücklich das Rutschen erklärt."

xliv Ibid.

"Was würde, ja was müßte man dazu sagen, wenn ein Violinist oder Violoncellist auf die Idee verfiele, einen Finger für untauglich erklären und das Richtige und Zweckmäßige einer daraus zu folgernden Applicatur darthun zu wollen?"

xlv Müller, "F. C. Franke's Anleitung": 244.