Abstract: This study addresses the discrepancy between the range of Beethoven's double bass parts and the instrument or instruments in use in Vienna in his day. Scholars and musicians have complained about Beethoven's apparent disregard for the instrument's capabilities since the middle of the nineteenth century. A systematic examination of Beethoven's orchestral writing for the double bass shows that this reputation is undeserved. In fact Beethoven paid close attention to the lower compass of the double bass throughout his orchestral writing: a clear boundary of F is observed to op. 55, and thereafter E, though F still obtains in some late works. Beethoven's observance of the F boundary suggests that he was writing for the Viennese five-stringed violone, and not the modern form of the instrument, as has previously been assumed in scholarship. Evidence pointing to the use of this instrument is presented.

Some of Beethoven's bass parts between op. 55 and op. 125 do in fact descend to C (sounding C1); yet there is no evidence supporting the existence of a double bass instrument capable of C1 in Beethoven's day. Possible explanations for these violations of the compass of the double bass are discussed. These focus on the possibility of simple proofreading error, and on evidence for the unwritten practice of reinforcing the double bass with one or more contrabassoons. The contrabassoon in Beethoven's day had a lower compass of C1, and Vienna was an early center for its production and use. Finally, out-of-range pitches are compiled and presented in table form.

Since the middle of the nineteenth century, scholars and musicians have complained about Beethoven's orchestral writing for the double bass. Central to these complaints are the appearance of pitches that fall outside the lower compass of the instrument. Some of Beethoven's double bass parts do in fact descend to C, sounding an octave below the open C-string of the cello. Yet double bass instruments in use in Vienna in the early nineteenth century are supposed by the scholarly literature to have had a lower compass of E. Despite modern assertions of the capability of C1 in the classical period,1 there is no evidence to support the existence of a stringed bass instrument capable of sounding C1 in Beethoven's time.2 In this article I will examine the circumstances and evidence surrounding this discrepancy, and attempt to address these complaints systematically. I will show that the Viennese five-stringed double bass (contemporaneously referred to as the violone), with its lower compass of F and the so-called "D Major" tuning (F A d f# a), was in fact still in use in Vienna in Beethoven's time, and that many of his double bass parts in fact match that instrument's lower compass. I will then discuss possible explanations for out-of-range pitches that appear in Beethoven's double bass parts.3

A significant portion of the problem addressed in this study is directly impacted by the condition of primary sources; sources for Beethoven's music are well known to be, at best, problematic. Study of source materials is, unfortunately, outside the scope of this study. I have not attempted to improve upon, nor do I take issue with, the work of scholars who have prepared the published editions of Beethoven's works. I take the position that the published editions reflect Beethoven's intentions, and I also hold Beethoven responsible as "editor" of his bass parts. I realize, however, that neither of these assumptions are safe ones. The primary sources for Beethoven's music reflect a complicated process of the various stages of revision and publication, and how much influence individual copyists, editors, and performers have had in producing this corpus of source material is virtually impossible to know. I have therefore accepted the published editions as "fact." Further study of source materials with a specific view to the problems raised in this study may provide more concrete support for the explanations I propose here, but it is also possible that definitive solutions to the problem outlined here are simply out of reach.

Most of Beethoven's orchestral music was written between 1800 and 1815, and nearly all of it was performed for the first time in Vienna. That city was unquestionably Beethoven's musical milieu, and he must have known both its practices and its musicians intimately.4 In fact, Beethoven's orchestral works up to op. 50 (Symphonies 1 and 2, Piano Concertos 1-3, Violin Romances 1 and 2, and the Overture to The Creatures of Prometheus) maintain a clear and consistent lower boundary of F in both their double bass and cello parts. Certain later works also observe the same boundary, although the capability of at least E for the double bass seems to be assumed from about op. 55 onward. Beethoven's consistent respect for this boundary in his early repertoire strongly suggests that he was writing for the Viennese five-string, or violone. His conspicuous avoidance of the lowest part of the cello's range in this repertoire, from E down to its resonant open C string, also strongly suggests the accommodation of an instrument with a lower compass of F. The same practice is clearly observable in Haydn's orchestral music. James Webster and Sara Edgerton have shown that in order to maintain octave doubling in the sixteen-foot register, Haydn routinely sacrifices the lowest portion of the cello's range, in deference to the double bass's inability to descend lower than F. But when the violone is either absent or rises above the cello to play a concertante role, Haydn is then free to make use of the deepest portion of the cello's range, and indeed he does so in those situations. Likewise, Beethoven deploys the bottom of the cello register freely in music from this same period where the double bass is not present (e.g., the op. 18 string quartets, and the op. 5 cello sonatas), or when the cello plays a more independent role in orchestral music (Beethoven does not accord the double bass a soloistic role on its own, as Haydn, however infrequently, did); it is not as though he is not aware of the effectiveness of this portion of the cello's range. Moreover, Beethoven utilizes the lowest portions of the ranges of the violin and viola extensively and to great effect, in both chamber and orchestral music from the same period. The all but total absence of this E to C register in the cello part from the whole of his orchestral music to op. 50, is therefore striking. Deliberate accommodation of the lower compass of the double bass, and specifically a double bass whose lowest note was F, is the only credible explanation for this absence.

The Viennese five-string has been studied extensively in its solo and concertante roles, but its use in the orchestra has not been as thoroughly considered by modern scholarship. Nonetheless, this instrument was in fact still in use in orchestras in Vienna in 1800. Beethoven gave the first public concert of his own music on April 2, 1800, at the Burgtheater in Vienna. The program included the first public performance of Symphony no. 1, and either the first or second of his piano concertos — most likely the second.5 Beethoven contracted the Italian Opera Orchestra of the Viennese Hoftheater (there was a German Opera company as well; the Italian was reputed to be the better of the two). A review of the concert appears in the October 15, 1800 edition of the Allgemeine Musikalische Zeitung. Double basses are not specifically mentioned in this review. However, after noting that "this was truly the most interesting concert in a long time," the correspondent offers his opinion that "the orchestra of the Italian opera made a very poor showing," and continues, "the faults of this orchestra, already criticized above, then became all the more evident."6 The writer refers to a segment appearing seven columns earlier in the same edition, which discusses the Italian Opera more generally. This segment addresses the orchestra's double basses specifically:

As for the violones, one might wish that not all five of them would be five-stringed, and that the gentlemen would be a little quieter. During great fortes, one hears more scraping and rumbling than clear and penetrating sound, which would contribute to the whole.7

The attitude reflected in the notice is certainly not a positive one, and possibly indicates a changing disposition toward the use of the Viennese violone in the orchestra. Still, according to this writer, all five players in the orchestra were playing on five-stringed instruments; in Vienna, in 1800, these can only have been Viennese five-stringed violones. The writer even uses the term "violon." Beethoven's accommodation of the lower compass of this instrument is plainly discernible in the music played on this concert: all of it clearly observes a lower boundary of F in both its cello and double bass parts.

A second piece of evidence comes from a letter written by Sir George Smart, the English conductor. Smart traveled to Vienna in 1825 to discuss Beethoven's Ninth Symphony with the composer. Performance of the work in London had been problematic, and Smart sought to deepen his understanding of Beethoven's intentions. He later recalled, "the double basses here [Vienna] had four strings and Mittag said some had five — but with three Dragonetti does more than I have yet heard."8 Twenty-five years later, the report is undeniably that the instrument is still in use. This evidence is corroborated by Meier's assertion that five-stringed instruments were produced in Vienna until 1830; it is difficult to understand why they would be produced if there was no demand for them.

The presence of known practitioners of the Viennese tuning in Viennese orchestras of the early nineteenth century can also be documented to some extent. Georg Joseph Sedler (1750-1829) was a member of the Hofkapelle from at least 1793 until his death in 1829.9 Focht writes of Sedler that "his reputation as a virtuoso double-bassist extended far into the nineteenth century," which points strongly toward his use of the Viennese tuning, since virtuosic music for fourths-tuned double bass — at least in Vienna — did not exist at this time. Johann Dietzel (1754-1806) was engaged in Haydn's ensemble at Esterházy until 1790, and then again from 1802 until his death. Between these periods he was employed by the Hofkapelle in Vienna, and according to Focht is known to have participated in the first performance of Beethoven's Septet op. 20, on April 2nd, 1800.10 This assertion is corroborated by Mary Sue Morrow's Viennese concert calendar for 1761-1810, which lists "Herr Schuppanzigh, Schreiber, Schindlöcker, Bähr, Nickel, Matuschek, and Dietzel" as having participated in the septet.11 Haydn had some superlative words for Dietzel, calling him "the only good double bass player in Vienna and all of the Hungarian Empire."12 This long-time association with Haydn's ensemble, whose instrumentarium is detailed by Sara Edgerton (see below), strongly suggests that Dietzel was a practitioner of the Viennese tuning. His participation in the premiere of Beethoven's septet also suggests his use of the low-string scordatura practice described by Focht13, and discussed below — the double bass part of the septet has low E-flats in its slow movement.

Friedrich Pischlberger (1741-1813) gave the first performance of Mozart's "Per questa bella mano" in 1791, and is known to have consulted with both Mozart and Pichl about the five-string violone;14 his use of the Viennese tuning cannot legitimately be questioned. According to Focht, Pischlberger is known to have been a musician at the Viennese Hofkapelle, and later at the Theater an der Wien, the orchestra that Beethoven contracted for his second Academie in 1802. Theodor Albrecht corroborates this assertion in his article on the double bass player Anton Grams.15 Taken together with the documentary evidence presented above, the presence of these players in Viennese ensembles connected with early performances of Beethoven's music shows that the Viennese tuning was still in use in orchestras in Vienna at the turn of the eighteenth century. It is possible, perhaps even likely, that the popularity of the tuning was already in decline at this point; a changing attitude toward the instrument is certainly reflected in these sources. However, it is clear that the instrument and its range were well known in Vienna at the turn of the eighteenth century. This knowledge is reflected consistently in Beethoven's orchestral music to op. 50, and, if less consistently, in his later music as well.

Beginning with the Eroica Symphony, op. 55, pitches below F appear in Beethoven's double bass parts with increasing frequency. Apart from the concurrent rise in popularity of the four-stringed bass tuned E A d g, no contemporary development in double bass technology accounts for this change in Beethoven's writing for the instrument; a reliable string that could sound C1 did not appear until much later. Yet C1 appears in the double bass part already in op. 55. It is implausible that Beethoven would simply have forgotten about the limitations of the double bass in his third symphony and forward, when he had so clearly accepted them in earlier music. How can the appearance of pitches from E down to C in his double bass parts then be accounted for in this later repertoire? Possible explanations fall into two different categories. Briefly, some instances might be explained by the practice of reinforcing the double basses with one or more contrabassoons, while other instances appear to be simple oversights in editing or proofreading. Overlap and/or interaction between these two categories, amid the confusion of copying of parts and assembling players for a particular performance, is almost certain.

The contrabassoon in Vienna in 1800 had a lower compass of C (sounding C1; Beethoven even writes low B-flat for it in the ninth symphony). Beethoven may in fact have written pitches below E in the double bass part knowing that the contrabassoon, which would have played from the same part as the double basses, would be present in some cases, and knowing that double bass players would either transpose unplayable notes, or simply leave them out. Before proceeding to evidence supporting the inclusion of one or more contrabassoons to reinforce the double bass part, a brief discussion of eighteenth-century concepts and performance practices surrounding the "basso" voice will shed light on the set of assumptions that may have been in place for Beethoven in the early nineteenth-century.

Prior to the late eighteenth century, the part marked "basso" or "bassi" or "bassi tutti" by a composer was not written for a specific instrument. All bass-register instruments — cello, double bass (violone), bassoon, contrabassoon, theorbo, etc. — played from this same part, and if there were times when one or the other should drop out or play alone, this would be indicated with instructions like senza faggoti or soli violoncelli. According to Adam Carse,

The part in 18th century orchestral music which is most liable to be misunderstood is the bass part. The 19th century editions are apt to treat this as a part written specifically for cellos and double-basses; as a purely string part. Up to the time, quite late in the century, when composers did write specifically for these two instruments, only one bass part was written. It was the bass of the music in general, and was not designed for any particular instrument, nor did it embody the technical characteristics of the bowed string-instrument family. [...] The part was intended for all instruments of the bass register, and for all those whose function included playing the bass of the music.16

More recent scholarship disagrees slightly with Carse's characterization on two particulars: First, his assertion that the bass part was not designed for the "technical characteristics" of the stringed instruments disagrees with Edgerton's research on Haydn's bass parts. Edgerton asserts a high degree of tailoring for the specific characteristics of both the cello and the Viennese violone.17 In addition to an overall compliance with the lower compass of the violone, Edgerton notes features such as the concurrence of the top boundary of the cello's range (a') with that of the violone — this note is an octave harmonic on the top strings of both instruments. In Haydn's writing, passages utilizing this top note are carefully prepared by either rests or stepwise motion. Furthermore, figurations and passage-work utilizing alternation with the open-string notes a and d, common to both instruments, are prominent, while similar figurations employing the cello's G and C strings are avoided unless the violone is resting or has a different role, for example a concertante passage.18 Secondly, the appearance in the late eighteenth century of specific indications for both cello, double bass, and bassoon is often construed, as Carse implies above, to be the moment of the "separation" of the cello from the double bass. James Webster has argued, however, that the appearance of these indications merely follows a late eighteenth-century tendency toward terminological precision — a trend that has continued unabated to the present day — as opposed to reflecting a change in either scoring or performance practice.19

In the eighteenth century, the bassoon was an integral member of the structural bass in orchestral and other ensemble music, although it was not always given a discrete part. Eighteenth-century accounts of the instrument describe both its distinctive tone and its ability to articulate the bass voice in ensemble music.20 Its presence was, in many cases, assumed, and not necessarily indicated in the score. Adam Carse writes that "the old bass parts are also liable to be misunderstood in that it is not generally realized that they often include the bassoon part, even though that instrument was not mentioned by name."21 Carse points out that nearly every eighteenth-century orchestra was well supplied with bassoon players, and that in fact they were used in much greater proportion than they are today. In spite of that circumstance, he writes,

Dozens of scores may be examined without finding any bassoon parts. In operas or oratorios they may be found in only two or three numbers out of 30 or 40. Hundreds of the printed parts of the 18th century symphonies include no specific bassoon parts. Dozens of Haydn's symphonies in the Breitkopf and Härtel Complete Edition are without them, and of Mozart's 41 Symphonies in the same edition, 28 are without bassoon parts, and when they do occur it is almost entirely in the later works written from 1778 and onwards. Are we to suppose that these bassoon players, who were available in every orchestra, sat and did nothing when all these works were played? [...] Of course not. They played with the rest of the bass instruments as a matter of course, and only left the track of the bass part when some special melodic or harmonic part in the tenor register was written for them.22

Normal scoring for orchestral music in the mid-eighteenth century was strings in four parts (first and second violins, viola, and basso), plus pairs of oboes and horns. The oboes or horns might have been replaced or augmented by flutes or bassoons in specific situations. John Spitzer and Neal Zaslaw write that "this à 8 scoring, which could accommodate flutes alternating with oboes as well as bassoons playing along on the bass line — remained standard for published symphonies until the 1780s."23 In other words, in the early and middle eighteenth century the bassoon part was not written out, even though it was nearly always present. Only much later in the century, when the bassoon began to receive occasional obbligato parts, and when it began to function as the bass of the orchestra's wind choir, which sometimes played on its own, would the bassoon be allotted its own line in a score. More likely, a line above the basso part with the indication fagotto solo would suffice. Bassoon col basso, however, remained the rule until well into the nineteenth century, though the precise nature of how this manifested in practice is impossible to know with certainty.

Sara Edgerton has examined in detail practices related to the bassoon and its role in Haydn's ensemble at Esterházy. She reports that "by the second half of the eighteenth century its presence in 'symphonies' or 'orchestras' is clearly enunciated, both as a member of the bass part and as an obbligato voice in the ensemble."24 Modern scholars do not agree about the precise nature of bassoon col basso procedures; Landon has proposed and applied no fewer than five different principles in his editions of Haydn's works. These can be summarized as follows:25 1) Bassoon tacet in strings-only scoring; 2) bassoon tacet in slow movements, regardless of scoring; 3) bassoon col basso throughout; 4) bassoon rests during piano passages; and 5) bassoon plays a varied bass part. Edgerton concludes that the bassoon was most likely normally tacet in slow movements, but would otherwise play col basso throughout. While noting that information about bassoon col basso procedures is wholly absent from "hundreds" of eighteenth-century sources, meaning that a broad contemporary consensus about these practices is simply not available, she writes that "the bassoon is reported to be col basso throughout all symphonic movements primarily in post-1800 Austrian sources," and further, that "col basso throughout scoring for the bassoon [...] seems fairly common in Viennese sources from c. 1800 onward; prior to that time it is rarely reported."26 Use of the bassoon to reinforce the bass is thus reported to have been on the rise in Vienna at the turn of the eighteenth century — Beethoven's Vienna.

Bass instruments in Haydn's ensemble at Esterházy likely consisted of one player each on cello, violone, and bassoon. Interestingly, each of the musicians identified as violone players in Esterházy documents was hired as a bassoonist,27 suggesting a high degree of overlap in the functional duties of these instruments — evidently they were considered practically interchangeable. The age of the instrumental specialist had yet to arrive, and many musicians could, and were often expected to, fulfill multiple roles. Thus the "basso" role could be played by different instruments, according to circumstance, preference, and availability.

This aspect of classical performance practice, in fact a holdover from the baroque period, changed substantially over the course of the nineteenth century. Instrumental territories became more specifically defined in orchestration practices. Beethoven arrived to stay in Vienna in 1792, and commenced to learn his craft; this earlier conception of the "basso" role must have been stock in trade for him. But it is also certain that Beethoven endeavored to expand the sonority and range of the orchestra, and in particular its bottom register. According to Daniel Koury,

The fact that the orchestra changed in size during the course of the nineteenth century needs little documentation. Changes in sound were due not only to the larger number of players but also to the addition of instruments rarely if ever used in the eighteenth century, e.g., the English horn or contrabassoon.28

Referring to Beethoven's chamber music, James Webster has pointed out the systematic use and development of register as a compositional resource.29 The same evolution can be observed in Beethoven's orchestral music, which pushes both upward and downward in tessitura. Still, the double bass in Beethoven's Vienna was simply not capable of C1; nor did he imagine it to be. The contrabassoon, however, was capable of this register.

The contrabassoon is described in theoretical works as early as the late sixteenth century. It is mentioned in a newspaper notice describing Handel's upcoming season in 1740, and scored by Handel in two choruses from L'Allegro and in the Royal Fireworks Music. Charles Burney describes it in 1785, and W. T. Parke in his Musical Memoirs (1785-1830).30 It was used at a commemoration of Handel at Westminster Abbey in 1785. Notable technological developments occurred in Belgium in the late eighteenth century in the Tuerlinckx shop.31 The contrabassoon was a sixteen-foot instrument, from reed to bell, having a lower compass of at least C1. According to Lyndesay Langwill, Vienna was an early center for its use in the late-eighteenth and early-nineteenth centuries:

It would seem that, up to about 1850, the inclusion of the contra in scores depended entirely on whether it was locally available. As Vienna seems to have been the centre where the contra was always procurable, we find it in the scores of Haydn and Beethoven. It received little attention, however, from Mozart and less from Schubert, and it rarely occurs in German scores as it was first considered more suitable for military music.32

This assertion concurs with Adam Carse, who writes:

Some reinforcement of the bass part by a strong and flexible wind-voice was becoming an urgent need when orchestras were growing ever larger during the early years of last century [the nineteenth]. For this purpose Haydn and Beethoven had already made use of the double bassoon in Vienna, but that instrument was not to be found everywhere, and in France and England the choice fell on the old wooden serpent[...]33

Langwill includes a list of bassoon and contrabassoon makers to 1965. Table I presents information culled from his findings. Out of sixteen contrabassoon makers active between 1750 and 1825, seven are Viennese. One of these, Stephan Koch, made contrabassoons exclusively. Nearby Prague also appears to have been a center of production, with three contrabassoon makers active in this period. Referring to Viennese contrabassoons, Langwill notes that "actual instruments (bearing the Viennese makers' names) are preserved and there are records of their use in Vienna in Beethoven's time and after."34 He cites a salary record given by Köchel of the Viennese Hoftheater in 1807 which includes "1 Contrafagott," and notes that Kastner describes the use of two contrabassoons in a Viennese performance of Handel's Timotheus [sic] in 1812.35

The preceding firmly situates Vienna as a center for early use of the contrabassoon. Langwill provides the following list of compositions where Beethoven has included the contrabassoon: Symphonies 5 and 9; the Mass in D; the overture to King Stephen; The Ruins of Athens; and a number of marches and smaller pieces.36 He also refers to a memorandum in Beethoven's papers mentioning the contrabassoon — this same document is described in Thayer-Forbes Life of Beethoven, and is also referred to by Daniel Koury and A. Peter Brown. According to Thayer-Forbes, it was found among papers uncovered by Schindler after Beethoven's death. It reads: "At my last concert in the large Redoutensaal there were 18 first violins, 18 second, 14 violas, 12 violoncellos, 7 contrabasses, 2 contrabassoons."37 The program for the concert in question, from February 27, 1814, consisted of the seventh and eighth symphonies, a vocal trio, and Wellington's Victory. Apparently Langwill did not corroborate his list of Beethoven's works with contrabassoon against the program referred to by the memorandum; if he had, he might have noticed (as Daniel Koury and Asher Zlotnik have done)38 that none of the works on this program call for contrabassoon in their scores.

Contrabassoon Makers Active 1750-1825

Taken from Langwill, Bassoon and Contrabassoon, Appendix I.

| Name | Location | Dates | Comment |

| Baumann | Paris | 1800-30 | Contra advertised |

| 1825 | |||

| Doke, Karl | Linz | 1778-1826 | |

| Finke, F.H. | Dresden | c. 1822 | |

| Horak, Wenzel | Prague | (b)1788-(d)1854 | |

| Kies, W. | Vienna | c. 1820 | |

| Koch, Stephan | Vienna | (b)1772-(d)1828 | Contra only |

| Kuss, Wolfgang | Vienna | 1811-1838 | |

| Lempp, Martin | Vienna | 1788-1822 | |

| Peuckert & Sohn | Breslau | 1802-1835 | |

| Rott, Vincenz Josef | Prague | pre-1854 | (dates uncertain) |

| Schott, B. Söhne | Mainz | 1780 | |

| Tauber, Kaspar | Vienna | 1799-1836 | |

| Tuerlinckx, J. A. A. | Malines | (b)1753-(d)1827 |

The order in which Beethoven lists the instruments is also interesting. The contrabassoons are mentioned after the double basses, as though they belonged to the string group, or more specifically to the "basso" group; no other wind instruments are mentioned. An earlier note from Mozart suggests that this manner of grouping instruments is not without precedent. Describing the forces at a benefit concert at Vienna's Tonkünstler Societät, Mozart wrote to his father in 1781: "There were forty violins, the wind instruments were all doubled, there were ten violas, ten double basses, eight violoncellos, and six bassoons."39 Again, the bassoons are listed along with the other members of the "basso" corps, and after the strings. By category, Mozart names, in order, violins, winds, and the members of the "basso" (viola, cello, double bass, bassoon). Tonkünstler benefit concerts were unusual events that required participation from all the society's members, and often presented oratorios with enormous forces; the numbers indicated in Mozart's list should therefore not be viewed as normative in any sense. But as Peter Brown has pointed out, what should be noted are the proportions,40 and in particular that the bassoons in this case are not merely doubled, as with the other winds, but rather tripled.

Two further pieces of documentary evidence support the existence of this practice. The first is a set of parts was created for a performance of the Fourth Symphony, op. 60, in 1821, under the sponsorship of the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde. This work does not call for contrabassoon in its score. The performance took place in the Reitschule, a large hall normally used for training with horses. The orchestral forces employed were commensurately large, and Beethoven apparently added solo and tutti markings in the parts, indicating where the winds should be doubled and where they should play solo. Peter Brown41 and Bathia Churgin42 both refer to this performance and these parts. According to Nikolaus Harnoncourt43 the parts, which are now housed in the library of the Gesellschaft der Musikfreunde in Vienna, also include indications for contrabassoon. Second, the musician Joseph Melzer (1763-1832), listed by Köchel as both "Violonist" and "Fagottist", is described by Focht as having a secondary obligation to play contrabassoon.44 Köchel gives Melzer's tenure as "Violonist" with the Hofkapelle as 1813-1832, and as "Fagottist" from 1811-1824.45 This evidence shows that the overlap of the bassoon/double bass roles described above extended well into the nineteenth century. Moreover, it shows that contrabassoon was in fact present in this Viennese orchestra from at least 1811 to 1824, which agrees with Beethoven's description of its use at his concert in 1814, and with the 1821 performance at the Reitschule. Kastner's mention of the inclusion of contrabassoon in an 1812 performance of Handel's music (see above) also supports the existence of this practice.

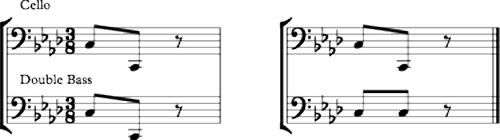

Beethoven did specifically indicate contrabassoon in the fourth movement of the Fifth Symphony, op. 67. This work, along with the Sixth Symphony, op. 68; the Fourth Piano Concerto, op. 58; and the Choral Fantasy, op. 80; was given its first performance at Beethoven's Akademie of December 12, 1808. The notated part for the contrabassoon is exactly the same as the double bass part in this piece, apart from sections where the contrabassoon is tacet. When the contrabassoon plays, its part is the same as that of the double bass. That the contrabassoon part is extracted from the double bass part is made clear by the following example:

Example 1: op. 67, iv, mm. 32 and 238.

In measure 32, Beethoven clearly accommodates the lower compass of the double bass; the arpeggio in the cello part starts from its open C string.46 Yet when the same material returns in measure 238, the correction is absent, and suggests possible oversight. Yet the correction in measure 32 for the double bass appears in the contrabassoon part as well, where it is not necessary; presumably, the extended lower compass of the contrabassoon was one of the principal reasons for its inclusion in the orchestra.

The significance of this example is twofold: first, it provides a clear indication that Beethoven did not suppose a lower compass of C1 on the double bass, even in works after op. 55; second, the appearance of Beethoven's accommodation for the compass of the double bass in the contrabassoon part provides evidence that the contrabassoon did not have its own discrete part. It is conceivable, though unlikely, that the discrepancy between measures 32 and 238 is intentional, and not an oversight; that Beethoven meant to show two different ways of executing the passage, taking for granted that the respective players would understand which one applied to them. Perhaps he even intended this subtle variation in contour; this last seems far-fetched indeed, since the effect would have been obscured by the cello part, which is the same in both instances. Indeed, why would Beethoven write the ungainly version appearing in measure 32 unless it was dictated by instrumental limitations? It is awkward, it changes the trajectory of the arpeggio, and it breaks the desirable octave doubling between cello and double bass. Far more likely is that the presence of the contrabassoon as reinforcement resulted to one extent or another in Beethoven's relaxed disposition toward the careful editing of the bass part for the compass of the double bass. Perhaps it was just plain carelessness. In either case, what this example and others like it make clear is Beethoven's awareness that the limited lower compass of the double bass was something that needed to be accounted for in crafting the bass part. Beethoven demonstrates this awareness repeatedly throughout his orchestral music, even in much later works, and even if he seems to forget the same in certain instances. The subsequent editorial decision to have the contrabassoon follow the double bass is probably a result of a too literal interpretation of "contrafagot col basso." It makes much more sense for the contrabassoon to follow the notation of the cello in this and other instances, thereby providing the sixteen-foot doubling that it is capable of, and that would seem to be the central reason for its inclusion in the orchestra. Given the ambiguity of contemporary information about col basso practices described above, a definitive conclusion on this matter may well be impossible to reach.

Beethoven's memorandum demonstrates that he used contrabassoons in a performance of the seventh and eighth symphonies, where they are not called for in the score. One may assume that at least one contrabassoon was also present for the concert of December 12, 1808, where the instrument is called for, in the Fifth Symphony. It is reasonable then to postulate that contrabassoon(s) might also have played in the other works on the program (Wellington's Victory and the Sixth Symphony, where the double bass part descends to C1 on several occasions), and therefore that Beethoven wrote down to C knowing that the contrabassoon would be present on this program. It is, however, curious that Beethoven indicated contrabassoon in the score for op. 67, and not in other scores, where it was evidently used in performance — perhaps he simply wanted to be certain of the weightiest possible bass sound in the fourth movement of the fifth symphony, where in other cases he adjusted the size (and instrumentation) of the bass group based on the performance venue and the size of the rest of the orchestra. Several sources describe the practice of varying orchestral forces based on venue and occasion in this period,47 and we also know that Beethoven was keenly aware of the "dynamic impact" of his music, as Daniel Koury has called it, and would have wanted to maximize its effect in any given venue — Koury describes a letter from Beethoven where he is keenly interested in the both the size and power of the orchestra and the characteristics of the hall for a performance of his music by the Philharmonic Society in London.48

Numerous examples from op. 55 and onward show that Beethoven clearly accommodated the lower compass of the double bass, while at the same time deploying the lowest part of the cello register — a departure from earlier classical practice, and from his own practice up to op. 50. This technique appears for the first time in the Creatures of Prometheus Overture, op. 43 (example 2), and reappears throughout Beethoven's orchestral works. Clearly, Beethoven wanted to utilize the deepest sonorities available to him, and to make the most of the orchestral resources at his disposal. He must therefore have had a keen awareness of the instrumental limitations he faced. Use of the contrabassoon to reinforce the double bass part in performance provides a logical explanation for the appearance of pitches in Beethoven's double bass parts descending to C1, and could in some measure account for the lack of attention to detail that is sometimes evident in the editing of these parts for the compass of the double bass. In other words: perhaps Beethoven was less than concerned with precise editing of these parts because he knew that they were playable on the contrabassoon. His memorandum certainly suggests that he counted the contrabassoon among the instruments of the bass instrumentarium.

Example 2: op. 43, mm. 4-12.

Another way to account for the appearance of notes below E in Beethoven's double bass parts is to demonstrate inconsistencies in proofreading in the source material. It is well known that Beethoven's manuscripts present considerable challenges to an editor; the most cursory examination of any autograph score is sufficient to make this point clear. Adam Carse has described Beethoven as a composer "who was maddeningly careless, who made untidy or illegible corrections, who often changed his mind, who sometimes appeared to be unable to make up his mind, and was clearly a most inefficient proofreader."49 Regarding the appearance of out-of-range pitches in the music of Mozart and Haydn, James Webster writes that

It would naturally be premature to conclude on the basis of the evidence presented here that pitches beneath the normal range of the double bass in music for that instrument by Mozart and Haydn are mere slips of the pen. But almost all such instances are, indeed, lacking in compositional weight, and there are very few of them that cannot be explained away on reasonable grounds. The alternative is to conclude that, contrary to documentary and stylistic evidence, Viennese double basses went down to C1 after all. The case for casual error seems far more plausible, however, especially in view of the occasional "corrections" these low pitches receive.50

Some instances of unplayable pitches in Beethoven's music are not similarly lacking in "compositional weight." But this does not preclude the possibility that many of them can be explained by carelessness. Jonathan Del Mar, editor of Bärenreiter's recent urtext edition of Beethoven's nine symphonies, has written that the "central problem" in editing Beethoven is that he "was human, and indubitably there are places where he made mistakes."51

A frequent consternation in Beethoven's bass parts, as described above, is that a part is "corrected" to accommodate the compass of the double bass in one instance, but then not similarly modified when the same material reappears at a parallel spot in the music. Another example of this type appears in the slow movement of the fifth symphony. Measures 31 and 80 are parallel, containing the same cadence. According to Adam Carse, the autograph score has low C for both cello and double bass in both instances, while the 1826 score, which was authorized by Beethoven, has the low C for double bass in measure 31, but corrects this to c in measure 80. Carse also notes that the 1809 set of parts has low C in both instances; these were prepared by copyists, and it is entirely possible that Beethoven never even saw them, much less carefully inspected them.52 Modern editions follow the reading of the 1826 score. The version appearing in measure 80 strongly indicates Beethoven's awareness of the lower compass of the double bass, and suggests that the version in measure 31 is the result of simple oversight. The autograph score came first, of course, heeding only the lower compass of the cello, and was handed over to a publisher, who would prepare a galley score for correction by the composer. It is hardly remarkable, particularly for Beethoven, that the correction phase was often left incomplete. The copying and subsequent checking of parts was an extremely laborious and time-consuming process, while rehearsal and production periods were extremely short in Beethoven's early concerts — indeed for all concerts in Vienna in Beethoven's time — and conditions were not at all favorable for musicians in general.53 Considering these circumstances together with Beethoven's notorious lack of thoroughness and attention to detail, the resulting inconsistencies in his bass parts become somewhat easier to understand.

Example 3: op. 67, ii, mm. 31 and 80.

In some cases, editing for the compass of the double bass seems to proceed to a certain point in a movement, and then suddenly stop. The Ninth Symphony, op. 125, provides an example of this type. In measures 18-19 of the first movement (Example 2.3), the lower compass of the double bass is clearly accommodated to avoid D:

Example 4: op. 125, i, mm. 18-19.

A similar accommodation occurs again in measure 52. With the possible exception of measures 102-3, and 106-7, where the bassoons split D and d but the cello and bass remain on d, editing for the compass of the double bass stops entirely after this point. C-sharp and especially D appear extensively in the remainder of the first movement, but always when the cello and double bass parts are at written unison. The second movement seems likewise to be entirely unedited for the double bass. Passages where the double bass is separate from the cello, however, do not descend below E; all instances of pitches below E appear when the two parts appear in written unison. These two circumstances suggest once again that 1) Beethoven did not believe the double bass to be capable of C1, and 2) that not all of the written unison sections have been "corrected" for the compass of the double bass. It is also possible, as discussed above, that these sections were left unedited because Beethoven knew that the double bass part would be joined by contrabassoon, since that instrument is in fact called for in this piece. The precise degree of overlap and interaction between the potential presence of the contrabassoon on the one hand, and the lack of consistent editing for the double bass on the other is, unfortunately, impossible to ascertain with certainty. Some instances lean one way or the other, while some tolerate both explanations; still others remain ambiguous.

A third type of explanation is worthy of mention. Certain works or single movements seem to assume a consistent lower boundary in the bass part of E-flat or D. Examples are the first movement of the Septet, op. 20, and the March and Chorus from The Ruins of Athens, op. 114. In the case of the Septet, the lowest note throughout for either cello or double bass is E-flat; the later example has a lower compass of D. Interestingly, low D-flat seems to be avoided in op. 114, despite two occasions where it would have seemed to work very naturally, and where the cello could easily have executed it. These and similar examples suggest that Beethoven might have been aware of the practice of re-tuning the bottom string of the double bass as needed to D, E, F, or F-sharp. This practice is purported by Focht54 to have been in use in late eighteenth-century Vienna. It cannot have been used in works where, for example, E-flat is used in one passage and then C or C-sharp is found later, as in the first movement of the Seventh Symphony. Yet certain works seem to assume a consistent boundary that suggests the possibility of scordatura, where there would have been time to re-tune between movements of a piece or between pieces on a program. Beethoven's slow movements in particular often show a lower limit of E-flat, indicating that perhaps Beethoven thought this was practically feasible in slower tempi. This agrees with Johann Hindle's assertion of the effectiveness of lower notes "in adagios and pianos."55

Tables 2 and 3 list all instances of out-of-range pitches in the bulk of Beethoven's orchestral music. Table 2 lists works up to op. 50, where F is assumed to be the lower boundary, and Table 3 gives opp. 55 to 125, where E obtains. A series of late overtures (opp. 113, 115, and 124), are written in such a way that they could just as well be included in the first group of works, op. 15 to op. 50. These contain nothing whatsoever below F for the double bass, but on occasion make effective use of the cello's bottom register. Their editing seems to be, by contrast, careful and complete. Opp. 55 to 125 consists of 50 movements or single-movement works. 15 of these, or 30%, contain nothing at all below either F or E. The total number of notes exceeding the boundary of E is 417; of these, only 24, or 5.8%, occur in non-unison contexts, which is to say that they are less likely be explained by proofreading error. Thus 94.2% of out-of-range pitches in op. 55 to op. 125 occur when written unison obtains between cello and double bass.

Symphonies in this later group are the most problematic in terms of their editing for the double bass. With the exception of op. 93, these contain numerous instances of pitches below the compass of the double bass. A great many of these can probably be categorized as oversights, since Beethoven demonstrates his awareness of the compass of the double bass with numerous accommodations in these same works. The preparation by hand of a set of parts for the performance of a symphony would indeed have been a daunting task, and it is perhaps not surprising that some of the minutiae on occasion might have been neglected. Shorter works such as overtures presented less of a challenge in this respect, and this may explain their more careful editing as a group. Symphonies were certainly Beethoven's most highly anticipated works. In addition to writing and editing the music, the composer had to manage all of the logistical aspects of the performances, which may well have infringed upon his available resources — temporal, physical, and mental — for the careful editing of bass parts. Moreover, inclusion of the contrabassoon to reinforce the bass part in the sixteen-foot octave is a factor that could have made Beethoven less concerned about the careful editing of these parts. Still, it remains clear that Beethoven accommodated the compass of the double bass throughout his orchestral music, from op. 15 to op. 125. His demonstration of this awareness suggests that instances where that same accommodation is lacking are likely to be cases of simple oversight.

Downward Range of Beethoven's Orchestral Works to op. 50

| Opus no./mvt. | Lowest Note | Notes Below F vc/cb measure no: pitch |

| 15/i | F | none |

| 15/ii | F | none |

| 15/iii | F | none |

| 19/i | F | none |

| 19/ii | E-flat | 69, 91, 92: E-flat |

| 19/iii | F | none |

| 21/i | C | 292: E; 293, 296, 297: C |

| 21/ii | F | none |

| 21/iii | F | none |

| 21/iv | F | none |

| 36/i | F | none |

| 36/ii | F | none |

| 36/iii | F# | none |

| 36/iv | F# | none |

| 37/i | F | none |

| 37/ii | F# | none |

| 37/iii | F | none |

| 40 | G | none |

| 43 | F# (cb)/C (vc) | for vc: 5, 6, 9, 10: C |

| 50 | F | none |

Out-of-Range Notes in op. 55 to op. 125

| Opus no./mvt. | Lowest Note cb |

Notes Below E for cb measure no: pitch |

Unis vc? Y/N |

| 55/i | C | 42: Eb | Y |

| 254: C | Y | ||

| 346-60: C, Db, Eb | Y | ||

| 486: Eb | Y | ||

| 512: Eb | Y | ||

| 55/ii | Eb | 3: Eb | N |

| 107: Eb | N | ||

| 181: Eb | N | ||

| 55/iii | F | none | |

| 55/iv | D | 84: Eb | Y |

| 213: D | Y | ||

| 217: D (2x) | Y | ||

| 221: D | Y | ||

| 225: D (2x) | Y | ||

| 233: D (2x) | Y | ||

| 241: D (2x) | Y | ||

| 245: D | Y | ||

| 357: Eb | Y | ||

| 400: Eb | Y | ||

| 403-407: Eb (8x) | Y | ||

| 459: Eb | Y | ||

| 56/i | C | 72: D | Y |

| 74: C | Y | ||

| 56/ii | Eb | 3: Eb | Y |

| 12: Eb | Y | ||

| (56/ii) | 23: Eb | Y | |

| 56/iii | C | 59-61: C (2x) | Y |

| 76-77: D (2x) | Y | ||

| 58/i | D | 65-66: D, Eb | Y |

| 97: D (2x) | Y | ||

| 99: D (2x) | Y | ||

| 58/ii | E | none | |

| 58/iii | D | 248: Eb | Y |

| 351: Eb | Y | ||

| 353: Eb | Y | ||

| (58/iii) | 401: D | Y | |

| 490: D | Y | ||

| 60/i | Eb | 245: Eb | Y |

| 60/ii | C | 33: Eb | Y |

| 53-4: Eb, Db | Y | ||

| 100-01: C, D, Eb | Y | ||

| 104: Eb | Y | ||

| 60/iii | F | none | |

| 60/iv | Eb | 103b: Eb | |

| 61/i | D | 334: D | Y |

| 61/ii | F | none | |

| 61/iii | F | none | |

| 62 | D | 45-50: Eb (5x), D (4x) | N |

| 254: Eb | Y | ||

| 67/i | D | 479: Eb | Y |

| 481-2: D | Y | ||

| 67/ii | C | 7: Eb | N |

| 9: Eb | Y | ||

| 31: C | Y | ||

| 56: Eb (3x) | N | ||

| 58: Eb | Y | ||

| 105: Eb (3x) | N | ||

| 113: Eb | N | ||

| 184: Eb | Y | ||

| 191: D, Eb | Y | ||

| 204: Eb | Y | ||

| 67/iii | Eb | 39-43: Eb (4x) | Y |

| 67/iv | C | 8-12: C, D (3x ea.) | Y |

| 80: C | Y | ||

| 214-18: C, D (3x ea.) | Y | ||

| 238: C | Y | ||

| 431: C | Y | ||

| 68/i | D | 175-81: D (6x) | Y |

| 68/ii | Eb | 5: Eb | Y |

| 118: Eb | Y | ||

| 68/iii | F | none | |

| 68/iv | C | 41-43: C, Db, Eb | Y |

| 49-50 C, D, Eb | Y | ||

| 135-6: C, D | Y | ||

| 68/v | C | 45: D | Y |

| 49: D | Y | ||

| 175-6: C (3x) | Y | ||

| 192: D | Y | ||

| 205: C | Y | ||

| 221: D | Y | ||

| 225: C | Y | ||

| 254: C | Y | ||

| 257: C | Y | ||

| 72/no.2 | 19: D# | Y | |

| 29: C# (3x) | Y | ||

| 35: Eb (5x) | Y | ||

| 104: C | N | ||

| 106: C | N | ||

| 307: Eb | Y | ||

| 478: C | Y | ||

| 485-6: C | Y | ||

| 72/no.3 | 16: D# | Y | |

| 73/i | Eb | 90: Eb (2x) | Y |

| 73/ii | F# | none | |

| 73/iii | Eb | 30: Eb | Y |

| 275: Eb | Y | ||

| 80 | E | none | |

| 84 | Eb | 3: Eb | Y |

| 11: Eb | Y | ||

| 74-81: Eb (8x) | Y | ||

| 148: Eb | Y | ||

| 245: Eb | Y | ||

| 92/i | C | 40-1: C (3x) | Y |

| 122: D# | Y | ||

| 137: C | Y | ||

| 142: D# | Y | ||

| 144: D# | Y | ||

| 146: D# | Y | ||

| 177: D# | Y | ||

| 218-19: C# (6x) | Y | ||

| 366-67: D (2x) | Y | ||

| 373-74: D (2x) | Y | ||

| 425: D | Y | ||

| 432-3: D# (6x) | Y | ||

| 434-5: D (6x) | Y | ||

| 436: C#, D (2x) | Y | ||

| 438: D (3x) | Y | ||

| 440: D (3x) | Y | ||

| 92/ii | E | none | |

| 92/iii | E | none | |

| 92/iv | C | 13: D (2x) | Y |

| 14: C# (2x) | Y | ||

| 15: D (2x) | Y | ||

| 16: C# | Y | ||

| 18: C# | Y | ||

| 138: D# | Y | ||

| 140: D | Y | ||

| 142: C# | Y | ||

| 144-5: C (2x) | Y | ||

| 259: D | Y | ||

| 318: C# | Y | ||

| 386-408: D# (22x) | Y | ||

| 413-16: D# (4x) | Y | ||

| 446: D | Y | ||

| 93/i | E | none | |

| 93/ii | E | none | |

| 93/iii | C | 67: C | N |

| 71: C | N | ||

| 73: C | N | ||

| 93/iv | E | none | |

| 113 | F | none | |

| 115 | C | 57: C | Y |

| 102: C | Y | ||

| 117 | D | 144: D | Y |

| 145: Eb | Y | ||

| 147: D | Y | ||

| 149: D | Y | ||

| 151: D | Y | ||

| 221-2: Eb (2x) | Y | ||

| 476: Eb | Y | ||

| 124 | F | none | |

| 125/i | C# | 156: D (2x) | Y |

| 224-28: D (4x) | Y | ||

| 391: C# | Y | ||

| 395: C# | Y | ||

| 397: C# | Y | ||

| 426: D (4x) | Y | ||

| 531-8: D (8x) | Y | ||

| 541: D (2x) | Y | ||

| 125/ii | C | 6: D (2x) | Y |

| 93-108: C (32x) | Y | ||

| 143: C | Y | ||

| (125/ii) | 151: D | Y | |

| 268-283: D (16x) | Y | ||

| 350: C | Y | ||

| 374: D | Y | ||

| 536: D | Y | ||

| 623-38: (32x) | Y | ||

| 673: C | Y | ||

| 681: D | Y | ||

| 798-813: D (16x) | Y | ||

| 880: C | Y | ||

| 904: D | Y | ||

| 125/iii | Db | 73-80: D (8x) | N* |

| 133: Db | Y | ||

| 135: Eb | Y | ||

| 125/iv | D | 316-319: (11x) | N |

| 919: D | N |

*Pitch content exactly the same as cello

1 H.C. Robbins Landon, The Symphonies of Joseph Haydn, (London: Universal Edition, 1955). 121; Alfred Planyavsky, Geschichte des Kontrabasses (Tutzing: Hans Schneider, 1970), 178; Bathia Churgin and Joachim Braun, A Report Concerning the Authentic Performance of Beethoven's Fourth Symphony, op. 60 (Ramat-Gan: Bar-Ilan University, 1977), 50-1.

2 James Webster, "Violoncello and Double Bass in the Chamber Music of Haydn and his Viennese Contemporaries, 1750-1780," Journal of the American Musicological Society 29 (1976): 421; Adam Carse, The Orchestra From Beethoven to Berlioz, (Cambridge: Heffer and Sons, 1948), 395; David Levy, "The Contrabass Recitative in Beethoven's Ninth Symphony Revisited," Historical Performance 5 (Spring 1992), 11.

3 For a more comprehensive treatment of the subject, including analysis of the bulk of Beethoven's orchestral music, see the present author's "Beethoven's Double Bass Parts: The Viennese Violone and the Problem of Lower Compass" (DMA Thesis, Rice University, 2013).

4 The bass player most frequently mentioned in connection with Beethoven's music is certainly Domenico Dragonetti (1763-1846). This is somewhat misleading. A great deal has been made of the famous virtuoso's visit to Vienna in 1799, and the allegedly deep impression made on the composer by his reading of one of the op. 5 cello sonatas. Legend has it that Dragonetti's extraordinary capabilities emboldened Beethoven to write as he did for the instrument in his orchestral music, and even that the recitatives in the Ninth Symphony were written for Dragonetti to play by himself. Evidence from Beethoven's conversation notebooks, however, indicates that this was in no way the composer's intention. In fact Dragonetti was not a part of Viennese musical culture in any way, and his own practices cannot be said to reflect those of musicians in Vienna in the late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. See Fiona Palmer, Domenico Dragonetti in England (1794-1846): The Career of a Double Bass Virtuoso (Oxford: Clarendon, 1997), 177-84; Levy, "Contrabass Recitative," 11-12.

5 The correspondent for Allgemeine Musikalische Zeitung reports on October 15, 1800, that "He [Beethoven] played a new concerto of his own composition [...]" Taken from Elliot Forbes, ed., Thayer's Life of Beethoven (Princeton: University Press, 1964), 255. According to the New Grove, the first concerto had already been performed in 1795.

6 Allgemeine Musikalische Zeitung 3, no. 3 (October 15, 1800), col. 49. Taken from Forbes, Thayer's Beethoven, 255.

7 Allgemeine Musikalische Zeitung 3/3 (October 15, 1800): col. 42. "Bey den Violons wäre zu wünschen, dass nicht alle 5, fünfsaitig, und die Herren etwas weniger wären. Bey grossem Forte hört man mehr drein reissen und Rumpeln, als deutlichen, durchdringenden Basston, der das Ganze erheben könnte." My translation.

8 British Library, Add. MS 41774, f. 26'. Taken from Palmer, Domenico Dragonetti, 75.

9 Ludwig Ritter von Köchel, Die Kaiserliche Hof-Musikkapelle in Wien von 1543-1867 (Vienna, 1869; repr., New York: Georg Olms Verlag, 1976), 94.

10 Josef Focht, Der Wiener Kontrabass: Spieltechnik und Aufführungspraxis, Musik und Instrumente (Tutzing: Hans Schneider, 1999), 35-36., 177.

11 Mary Sue Morrow, Concert Life in Haydn's Vienna: Aspects of a Developing Musical and Social Institution (Stuyvesant: Pendragon, 1989), 304.

12 Focht, Wiener Kontrabass, 177.

13 Ibid., 35-36.

14 Adolf Meier, "The Vienna Double Bass and its Technique During the Era of the Viennese Classic," Journal of the International Society of Bassists 8, no. 3 (Spring 1987), 14.

15 Theodor Albrecht, "Anton Grams, Beethoven's Preferred Double Bassist," International Society of Bassists Journal 26, no. 2 (2002): 20.

16 Adam Carse, The Orchestra in the XVIIIth Century (Cambridge, UK: Heffer and Sons, 1940), 122.

17 Sara Edgerton, "The Bass Part in Haydn's Early Symphonies: A Documentary and Analytical Study" (DMA Thesis, Cornell University, 1989), "Bass Part," chs. 5 and 6.

18 Ibid., 139-40.

19 Webster, "Violoncello and Double Bass," 425-6.

20 See Edgerton, "Bass Part," 163-168; and Appendix

21 Carse, XVIIIth Century, 124.

22 Ibid.

23 John Spitzer and Neal Zaslaw, The Birth of the Orchestra: History of an Institution, 1650-1815 (Oxford: University Press, 2004), 311.

24 Edgerton, "Bass Part," 168.

25 Ibid., 172.

26 Ibid., 177-78.

27 See H. C. Robbins Landon, Haydn: Chronicle and Works, vol. 1, Haydn: The Early Years, 1732-1765 (London: Thames and Hudson, 1994), 356.

28 Daniel Koury, Orchestral Performance Practices in the Nineteenth Century: Size, Proportions, and Seating (Ann Arbor: UMI Research Press, 1986), 85.

29 James Webster, "Traditional Elements in Beethoven's Middle-Period String Quartets," in Beethoven, Performers, and Critics (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1980), 99.

30 Parke, Musical Memoirs (1784-1830) (London: 1830), vol. 1, 42. Taken from Lyndesay G. Langwill, The Bassoon and Contrabassoon (London: Ernest Benn, 1965), 116.

31 The preceding summarizes Langwill, Bassoon and Contrabassoon, 112-116.

32 Ibid., 118.

33 Adam Carse, The Orchestra (New York: Chanticleer, 1949), 26.

34 Langwill, Bassoon and Contrabassoon,119.

35 Ibid. Handel did not write a work called "Timotheus;" perhaps Kastner refers to Alexander's Feast, in which the musician Timotheus plays a role. Alexander's Feast, in any case, does not call for contrabassoon in its score.

36 Ibid., 120.

37 Elliot Forbes, ed., Thayer's Life of Beethoven (Princeton: University Press, 1964), 576.

38 Koury, Orchestral Performance Practices, 117.

39 Taken from A. Peter Brown, The Symphonic Repertoire, vol. 2: The First Golden Age of the Viennese Symphony: Haydn, Mozart, Beethoven, and Schubert (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2002), 10.

40 Ibid.

41 Ibid., 16-17.

42 Bathia Churgin, "A New Edition of Beethoven's Fourth Symphony: Editorial Report." Isreali Studies in Musicology I (1978), 13-14.

43 Ernst Schlader, personal communication, 31 January 2013.

44 Focht, Wiener Kontrabass, 189. "Joseph Melzer war als Kontrabassist in der Hofoper mit der Nebenverpflichtung zum Kontrafagott angestellt."

45 Köchel, Kaiserliche Hof-Musikkapelle,94-95.

46 Interestingly, Stuart Sankey proposes altering this measure so that only the c on the second eighth-note of the passage is played in the upper octave, in order to "achieve maximum weight" for the passage. This is a most natural suggestion if one assumes a lower compass of E, but not if F is the assumed boundary, which may well have been Beethoven's reflex, even as he began to write E for double bass from op. 55 and onward. See Sankey, "On the Question of Minor Alterations in the Double Bass Parts of Beethoven," International Society of Bassists Journal 1, no. 4 (1975), 95.

47 See for example Koury, Orchestral Performance Practices, ch. 8; Brown Golden Age, ch, 1; Dexter Edge, "Mozart's Viennese Orchestras," Early Music 20, 1 (February 1992), 63-88.

48 Koury, Orchestral Performance Practices, 118.

49 Adam Carse, "The Sources of Beethoven's Fifth Symphony," Music and Letters 29, no. 3 (1948), 250-251.

50 Webster, "Violoncello and Double Bass," 434.

51 Jonathan Del Mar, "Editing Beethoven," Musical Opinion 133, no. 1472 (Sept/Oct 2009), 10-12.

52 According to Adam Carse, "Beethoven definitely authorized the publication of the parts of the Symphony in 1809 and of the score in 1826, but it cannot be taken for granted that he carefully checked the proofs of either before they were published and made sure that the music was exactly as he intended it to be. Even if there was no evidence that his proofreading was desultory, one might almost safely conclude that a man with his temperament–erratic, impatient, and impulsive–who was also careless and untidy in his habits, would never take kindly to the trying and tedious process of examining and collating every note, rest, slur, and sign on 121 pages of parts and 182 pages of full score. In fact it is as good as certain that he did no such thing." Carse, "Beethoven's Fifth," 253.

53 See Morrow, Concert Life; Clive Brown, "The Orchestra in Beethoven's Vienna," Early Music 16/1 (Feb 1988), 4-20; Otto Biba, "Concert Life in Beethoven's Vienna," in Beethoven, Performers, and Critics, 77-93; David Pickett, "A Comparative Survey of Rescorings in Beethoven's Symphonies," in Performing Beethoven (Cambridge: University Press, 1994), 205-6.

54 Focht, Wiener Kontrabass, 35-6.

55 Johann Hindle, Der Contrabass Lehrer, Ein theoretisch-praktisches Lehrbuch (Vienna: 1854), 7. Taken from Paul Brun, A New History of the Double Bass (Villeneuve d'Ascq: Paul Brun Productions, 2000),119.

© 2003 - 2026 International Society of Bassists. All rights reserved.

Items appearing in the OJBR may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the International Society of Bassists, and advance notification of the editors of the OJBR.

Any redistributed form of items published in the OJBR must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in The Online Journal of Bass Research in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] in [MONTH/YEAR], and it is republished here with the written permission of the International Society of Bassists.

Libraries may archive issues of OJBR in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of the OJBR and the International Society of Bassists.

Citations to articles from OJBR should include the URL as found at the beginning of the article and the paragraph number; for example:

Volume 3

Alexandre Ritter, "Franco Petracchi and the Divertimento Concertante Per Contrabbasso E Orchestra by Nino Rota: A Successful Collaboration Between Composer And Performer" Online Journal of Bass Research 3 (2012), <http://www.ojbr.com/volume-3-number-1.asp>, par. 1.2.Volume 2

Shanon P. Zusman, "A Critical Review of Studies in Italian Sacred and Instrumental Music in the 17th Century by Stephen Bonta, Burlington, VT: Ashgate Publishing Co., 2003." Online Journal of Bass Research 2 (2004), <http://www.ojbr.com/volume-2-number-1.asp>, par. 1.2.Volume 1

Michael D. Greenberg, "Perfecting the Storm: The Rise of the Double Bass in France, 1701-1815," Online Journal of Bass Research 1 (2003) <http://www.ojbr.com/volume-1-complete.asp>, par. 1.2.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.