Abstract: Avant-garde jazz of the1960s was characterized by rapidly expanding technical virtuosity and a dynamic individualism. Bassist Gary Peacock stands out in this era as a central collaborator to many of the iconic yet comparatively more documented jazz artists of the decade. By using a multi-dimensional motivic analysis of Peacock's performance on the seminal Albert Ayler Trio recording "Ghosts," a snapshot of this singular virtuosity comes into view, illuminating many of the innovative improvisation techniques that comprised his idiom. These techniques can be examined with regard to specific multidimensional motivic relationships characterized by rapidly changing expressive use of tempo, rhythm, melodic content, and ensemble interaction. Specifically addressed in the analysis is Peacock's unique application of disjunct tempo shifts and polyrhythm, along with stylistic breaks from common practice harmonic and melodic devices. The uncommon technical demands involved in the performance's execution will be highlighted with new notational methods that allow the representation of a performance that has previously defied conventional notational restrictions.

By early 1964, Gary Peacock had established himself in New York City as one of the most innovative and virtuosic bassists playing progressive1 jazz. His performing credits included work with Jimmy Giuffre, Paul Bley, Paul Motian, Gil Evans, Miles Davis, Tony Williams, and Sonny Rollins amongst numerous others. It was however his affinity for the collaborations with saxophonist Albert Ayler (and eventually with trumpeter Don Cherry) that was to have the most profound affect on the aesthetic and professional directions he was to pursue that year, leading him to resign his position as the regular bassist in the highly visible, lucrative, and comparatively structured Bill Evans trio.2

A prolonged collaboration between Peacock and Ayler in the second half of 1964 would result in some of the most influential jazz recordings of the decade, and would epitomize Ayler's mature approach as well as much of the emerging free jazz aesthetic. The initial trio, consisting of Ayler, Peacock, and drummer Sunny Murray, represents the logical extreme of the avant-garde from this era: unequaled dynamic range, an intensely developed vocabulary of extended techniques, the seeming abandonment of a traditional swing feel, exclusive reliance on open ended solo forms, and peripheral relationships to thematic material that maintained implicit connections to overarching dynamic characters rather than the development of pre-composed melodic or harmonic material. These extremes can be seen as a natural extension of the broken time rhythmic freedom being employed by earlier groups led by Evans, Coleman, Taylor, Bley, Giuffre, and Peacock himself, as well as the evolving chromatic and motivic nature of improvisation amongst the early 1960s jazz avant-garde.3

Recorded July 10th 1964,4 the album Spiritual Unity would become the group's most acknowledged document, praised as a milestone within the free jazz movement.5 As Wilmer states:

Spiritual Unity . . . revolutionized the direction for anyone playing those three instruments . . . Ayler, Murray, and Peacock had created the perfect group music. With it, Ayler felt that the ultimate stage in interaction had been reached. "Most people would have thought this impossible but it actually happened." . . . On Spiritual Unity, he said, "We weren't playing, we were listening to each other." (105)

While often categorized as free playing, redefined elements of melody, harmony, rhythm, and tempo are present albeit in a highly re-organized and improvised form. Peacock summarizes this group's approach:6

Quersin: If you eliminate the harmony, and then the beat, what do you have left to let you play together?

Peacock: Firstly there is an absence, with regard to improvisation, of notes - specific notes you have to play. This characterizes the whole approach: there is nothing that you have to play. To reduce jazz to its elements, there is no more melody in the improvisation. The melody is replaced by "shapes," which are produced by distances on the instrument, from one note to another, but with the note ceasing to be an integral factor.

In the examination of the music of the 1960s avant-garde, progressive, or "free" jazz, the work of Jost (1974), Meehan (2002, 2009), Bley and Meehan (2003), and Cogswell (1995), provide the nascent approaches to the motivic analysis of improvised music. This approach breaks down the building blocks of an improvisation into the definable and essential characteristics of various musical gestures. Jost demonstrates this approach in the analysis of improvisations of Ornette Coleman through a cataloging of phrases utilizing letters, indicating connections between phrases based upon these essential rhythmic, melodic, and register characteristics. This approach is coupled with narrative descriptions of the phrases themselves to outline the various relationships. Cogswell expands Jost's method further to include a system that identifies melodic chain associations (MCAs) that can be demonstrated and analyzed in terms of specific qualities of rhythm, pitch, contour, initial/terminal/dovetailing variations, repetition, and step progressions.

The highly original playing involved within "Ghosts" requires the drawing upon of the above analytical techniques, specifically the lettering system and narrative descriptions of the multilayered motivic qualities employed by Jost. These methods have the additional benefit of the flexibility needed to demonstrate the overlapping and non-hierarchical manner in which numerous motivic characteristics can simultaneously exist across and between sections of the improvisation.

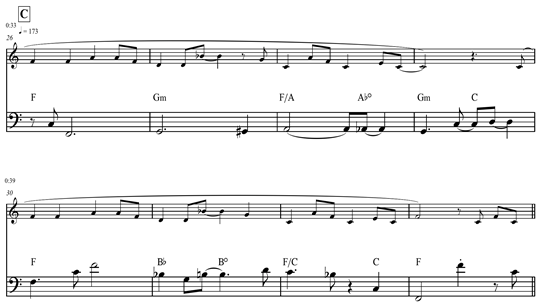

Ghosts captures Peacock's tone and unfettered free playing in one of the most influential of Ayler's compositions. Individual saxophone and bass improvisations follow Ayler's raucous, celebratory, diatonic, and in-time melody7(Figures 1-3). The folk-like character of the composed line contrasts starkly to the improvisations that will follow. Indeed Peacock's accompaniment underneath Ayler's solo improvisation is experienced as a concurrent extemporization of its own, with little recognizable connection to common practice accompaniment roles. The dynamic and rhythmically dense torrent of gestures in Peacock's playing can be characterized partially by the lack of predetermined rhythmic and melodic referents, extreme harmonic mobility, and oblique (if any) relationships to thematic or harmonic sequences contained in the head. Peacock's furiously active performance primarily takes the form of a kind of integrated rhythmic surge, responding to Ayler and Murray's playing with a myriad of fleeting melodies, tempos, timbres, and dynamic gestures that maintain complex motivic characteristics despite what has been dismissed as "satirical comedy"8 due to these potentially impenetrable layers of surface level complexity.

Figure 1. Measures 1-25

Figure 2. Measures 26-33

Figure 3. Measures 69-76, out head. Peacock prolongs his circle of fifths gesture in m. 72 by connecting E to A in a linear chromatic fashion before the deceptive resolution of the phrase to Db.

Peacock's playing displays several principle characteristics throughout the recording: 1) it can be broken down into a series of discreet yet overlapping phrases, with onset and offsets separated by rest or stark changes in register, dynamic, and/or tempo; 2) phrases contain discreet and observable contour, intervallic, rhythmic, pitch content, and expressive characteristics; 3) the flow of these phrases is rapid and intensely dense, offering an abundant production of diverse ideas with only rare instances of substantial pause; 4) phrases demonstrate extreme virtuosity and formidable technical demands inherent to their execution; 5) Peacock's playing is essentially responsive in nature, with the nature of these responses (to other musicians or to previous phrases played by the bassist himself) creating an ever increasing volume of moment to moment contrast; 6) the playing displays, according to Peacock9 a lack of self-consciousness that would impede the exceptional velocity and timing characteristics displayed throughout; 7) phrases contain a variety of discernable tempos, sometimes rapidly changing, yet measurable through measure and markings.

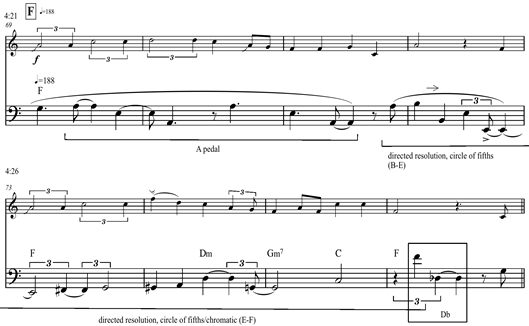

Pulse and tempo, as a defining characteristic of Peacock's improvisation, is maintained, albeit with rapid moment-to-moment changes and phrase-to-phrase developments. These tempos will be notated throughout using approximate (≈) tempo markings. These discernable tempos (and, more importantly, the shifts between them) combine with Ayler's expressive and unorthodox phrasing, creating a potential for increased perceptual dissonances (acknowledging that perceptual dissonance is relative and unprovable in some cases) via the creation of multiple and dissimilar juxtapositions of musical time, harmony, timbre, and densities. These unpredictable changes in tempo also serve as primary variations in perceived energy and motion, a unique contribution by Peacock to the ensemble that often contrasts the approaches heard from Ayler and Murray. Figure 4 demonstrates the nature of these contrasts via a two-dimensional modeling of Peacock's comparatively terraced approach to tempo, underneath the gradually shifting levels of density and velocity that make the specific notation of a regular pulse in the notation of the saxophone improvisation often illogical and/or impractical.

The juxtaposition of speeds and unpredictable compression and expansion of rhythm in each player's improvisation will now be characteristic for the remainder of the performance, creating a strong rhythmic polyphony that can obscure the perception of individual rhythms, as well as a perpetual motion from the ensemble as a whole that can potentially consume the details within the individual parts. The density of the rhythmic interplay often prevents the initial perception of these individual melodies due to substantial interference from other players' contributions. The constant interplay of these various speeds contributes to an ensemble texture that consumes any fleeting tempo information contained within individual phrases. This could initially suggest that Peacock is playing in a stream of consciousness manner, utilizing a kind of evolved rubato devoid of more detailed rhythmic components. However, these components do exist, and with a tremendous degree of observable detail.

Figure 4. A perceptual diagram of concurrent velocities; Ayler (top) and Peacock (bottom). While Peacock segments his accompaniment into short fragments with clear yet unpredictable tempo changes from one phrase to the next, Ayler's solo accelerates and/or slows within the characteristically long phrases themselves without a constant articulation of unwavering tempo.

Ayler and Peacock begin their improvisations at 0:44 at the tempo of ♩≈ 184, only slightly slower than the original ♩≈ 188 used for the melody at letter A (Figure 5). This tempo, as an explicit connection to the theme, will reappear sporadically throughout the performance as a significant rhythmic characteristic. With this tempo connecting moments of Peacock's improvisation to the melodic presentation, the tempo of a given phrase (apart from its melodic, harmonic, rhythmic, interactive, and timbral characteristics) becomes a point of improvised expression, allowing direct or remote connections to the theme, another musician, and various instances of rhythmic dissonance via changing amounts of phrase-to-phrase congruency. These tempo shifts provide a means of tracing a type of "tempo crescendo" throughout the performance.

Figure 5. Solo transition

Peacock's rhythmic dissonance then begins to intensify as his phrases begin to sequentially slow in tempo. This begins at 0:44 with ♩≈184, followed by a short gesture at ♩≈ 162, a longer phrase slower still at ♩=153, and then reversing direction and accelerating to a slightly slower version of the original tempo, ♩=179 at 0:54. Peacock's line here is divergent in tempo, creating an obscured perception of meter between the bass and saxophone. The rallentando in Peacock's lines diverges in number of pulses, with two less beats notated when compared to Ayler. Their tempos converge again however for the interactive realignment of call and response at 0:54. Here Peacock extends the end of Ayler's phrase, finishing it and momentarily joining the two improvisations into a single gesture; Peacock essentially "finishes" Albert's phrase. Peacock furthers this connection by returning to Ayler's tempo and resolving to a tonic unison albeit via contrary motion, from below rather than from above.

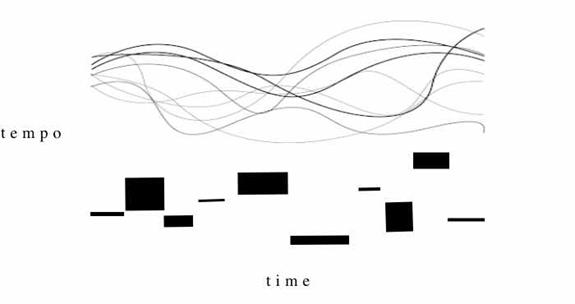

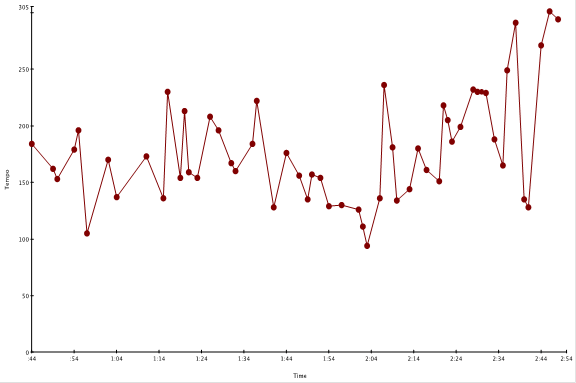

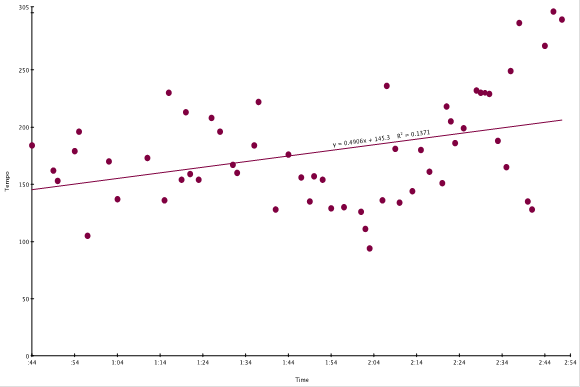

In these phrases Peacock can be heard slowing down the tempo of his improvisation, but doing so at the phrase level (i.e., phrase by phrase) rather than gradually changing velocity within the lines themselves, as in the extreme form of rubato Ayler frequently employs above. In these cases, various recurrent tempos can be heard as motivic characteristics, potentially independent of other gestural attributes within the phrase. This is evident when examining Peacock's 56 individual phrases that occur underneath Ayler's solo, the individual tempos that range from ♩≈ 94 to ♩≈ 301 appearing in Figure 6. While these tempos can often shift dramatically, a steady overall acceleration in the median tempo of his playing is observable. This increase in velocity mirrors the steady intensification of Ayler's improvisation.

Figure 6. Tempo fluctuations 0:44-2:54

Figure 7. Best-fit line, median tempo acceleration

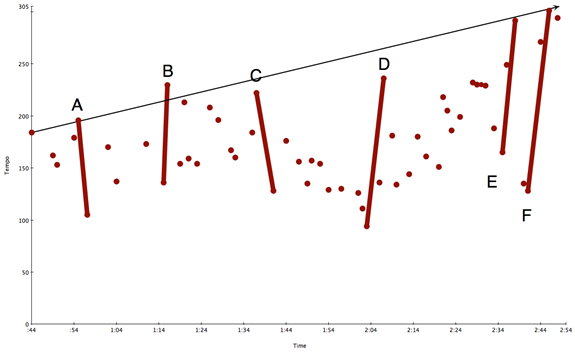

While the specific sequencing of tempos varies, the overall acceleration of Peacock's lines is evident when plotting a best-fit line through the entirety of the solo (Figure 7). This line shows that throughout Ayler's improvisation Peacock increases his overall phrase tempo in parallel to the increases in Ayler's dynamics and density, with both musicians peaking at the conclusion of the saxophone solo. Further, Peacock's tempo employs increasingly large distances between neighboring tempos, between 0:55 and 2:50 (Figure 8. A-E). These boundary tempos increase in distance as Ayler's solo progresses, beginning with ≈100 bpm (A) then widening to a 179 bpm at the climax of the improvisation (F).

Peacock seems to be mirroring layers of complexity, as well as timbral and dynamic dissonance produced by Ayler, but doing so through an acceleration of, and unpredictably dissonant shifts in speed. Yet simultaneously within these abrupt shifts is a gradual acceleration of the performance's original tempo, which can be heard by plotting an additional best-fit line for the upper tempo boundary from the onset of the section. By examining the upper tempos one can observe a gradual acceleration of the performance's original tempo (♩≈184) to the Ayler's climax (♩≈291), with the majority of tempo variety occurring below the original.

Figure 8. Boundary Tempos

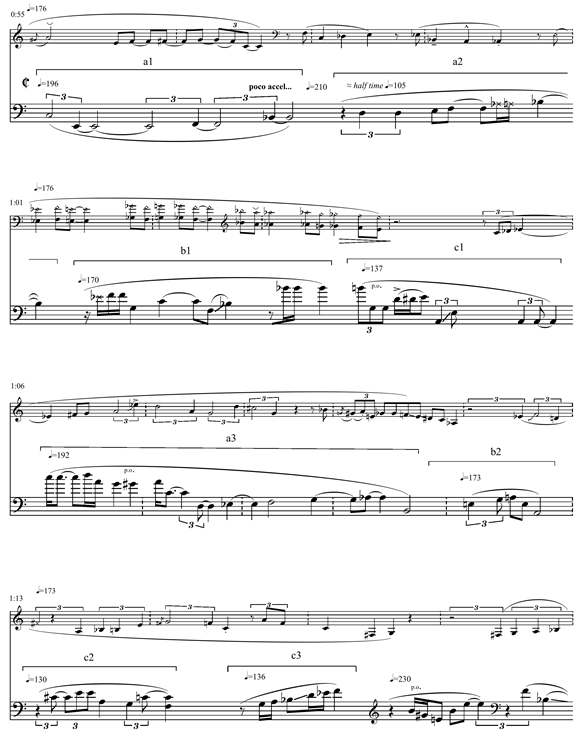

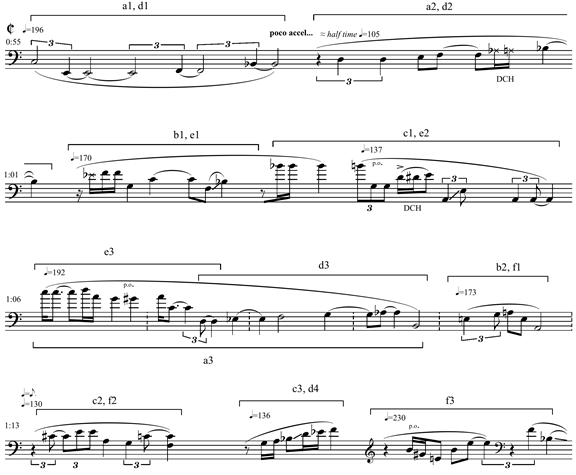

The detailed nature of individual tempo recurrence can be seen in Figure 9 (0:55-1:18). Peacock begins this section roughly a tempo, (♩=196) with the half note triplet gesture recalling Ayler's cut time melody. While Ayler maintains a loose and expressive rubato rooted in the pulse of the melody, Peacock's utilizes a few specific and repeating pulse streams. The first (♩=196, a1) incorporates a slight accelerando up to ♩≈ 210, before simultaneously dropping into a half time feel, ♩≈ 105 (a2) and labeled due to this transformational relationship.10 A variation of the original again returns at 1:06, with ♩≈ 192 (a3).11 A second slower tempo stream then begins at 1:02 (♩≈ 170, b1), and will return again at 1:12 with a short phrase at ♩≈ 172 (b2). The third tempo motive, slower still, occurs at 1:04 (♩≈ 137, labeled c1), and returns at 1:13 (c2, ♩≈ 130), which is immediately followed by an additional phrase at 1:15 (c3, ♩≈ 136). Within these twenty seconds of music, a great variety of textures are created through these changes in tempo, the shifts in velocity between phrases becoming a predominant characteristic of Peacock's texture. As the accompaniment progresses, certain tempos (♩≈ 196, ♩≈ 170, ♩≈ 136, and ♩≈ 154 in particular) will recur throughout the tenor solo.

Figure 9. Tempo motives, 0:55-1:18

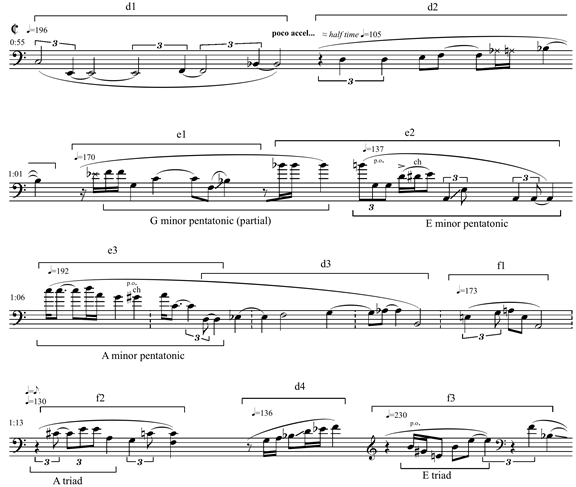

This segment also displays recurrent melodic devices, which are not necessarily joined to the tempo characteristics described above, and will often go against the written phrase markings. This quality creates a secondary layer of connections across phrases that are otherwise separated by onset and tempo. These melodic qualities are indicated in Figure 10 as bracketed motives based on these purely melodic/intervallic characteristics.

While the motives can vary in terms of length, they contain overt similarities specifically in the dominant characteristics of contour, boundary intervals, and pitch content. The first group of phrases contains ascending stepwise motion and longer note values, shown in phrases d1, d2, d3, and (in a rhythmically diminished form) d4. Motives e1-e3 are each characterized by a stepwise ascent followed by a large interval drop that then descends further in a zigzagging motion. Motive e1 begins with the ascending Eb-F followed by the descent from the high F to G before then working downward in wide interval leaps to Bb. This gesture contains the wide boundary interval of an octave (F-F). A similar shape occurs in motive e2, where again the step wise Bb-B is followed by a downward leap of a major 10th before rising and falling again, eventually coming to rest on the low A. The intervallic distance of the phrase is similarly wide, over two octaves away from the initial pitch. Phrase e3 contains a high C-D stepwise motion and is again followed by a terraced descent downward, a full two octaves to the open D string. The presence of articulation devices such as glissando (e1-e2) and the double chromatic approach (e2-e3) further link these phrases. While containing separate melodic characteristics, these d-e motives are often linked using specific pitches, such as the Bb which serves as a terminal pitch for gestures d1, d2, and e1 and will be used as the initial pitch of motive e2 transposed up the octave.

Figure 10. Melodic motives, 0:55-1:18

Motive f1 contains an incomplete but recognizable harmonic referent (A-7) before ending with the characteristic interval of a perfect fifth. This is echoed in motives f2 and f3, where each motive features contrasting triads that conclude with a harmonically foreign descending perfect fifth interval, C-F and F-Bb respectively. The accentuation of incongruent pitches at the end of a phrase containing an otherwise overt harmonic element will also be a recurrent feature of many of Peacock's lines, acting as a dissonant harmonic accent, "erasing"12 any momentary aural connections to a stable tonality. This mirrors the regular disruptions in tempo that prevent the perception of a predictable and dominant pulse stream.

The multidimensionality and non-hierarchical quality of Peacock's motivic characteristics are demonstrated by an overlapping use of tempo, melodic, and harmonic elements. The e1-e3 motives are marked by the use of overlapping pentatonic scale fragments, albeit presented with wide, disjunct intervallic movement that obscures a more obvious melodic pentatonic identity. These include a G minor pentatonic without the D (e1), E minor pentatonic (e2) with a chromatic passing tone (ch), and an A minor pentatonic minus an E (e3). These scales are used across phrases, adding an additional layer of motivic interaction, but now based on fleeting tonalities that are not in alignment with the onset and offset of phrases or tempo. While the perceptual weight of these tonalities is often consumed by the impact of the rhythm, tempo, and intervallic variations employed (not to mention the perceptual interference of Ayler's often purely timbral improvisation) they point to an important expression of polyrhythm and inherent layers of complexity within the piece.

These relationships are demonstrated in Figure 11, where motives (a-f) cut across phrases in a variety of ways. The use of melodic motives carries across the notated tempo-based phrasing (e1, e2, f3), or segments a line into two separate melodic gestures within the single phrase (e3, d3). While tempo remains a primary determiner of perceived phrases (confirmable by the separation through rests) melodic motives can carry across tempo and rest-defining boundaries.A complex network of relations now appears across phrases when each of the aforementioned tempo and melodic gestural characteristics are combined. Motives such as a1 and a2 combine with motives d1 and d2, while other motives (such as e1 and e2 that contain similar intervallic content) utilize separate tempos (b1, c1). A single tempo (a3) could contain more than one distinct melodic motive (e3, d3), while some tempo motives (c3) may reappear with more varying melodic material (d4) than previous versions (e2, f2).

Figure 11. Combined melodic and tempo motives, 0:55-1:18

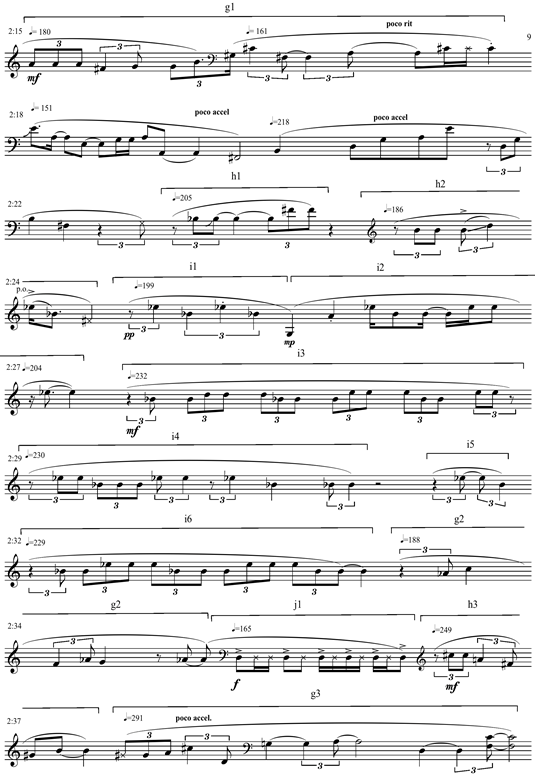

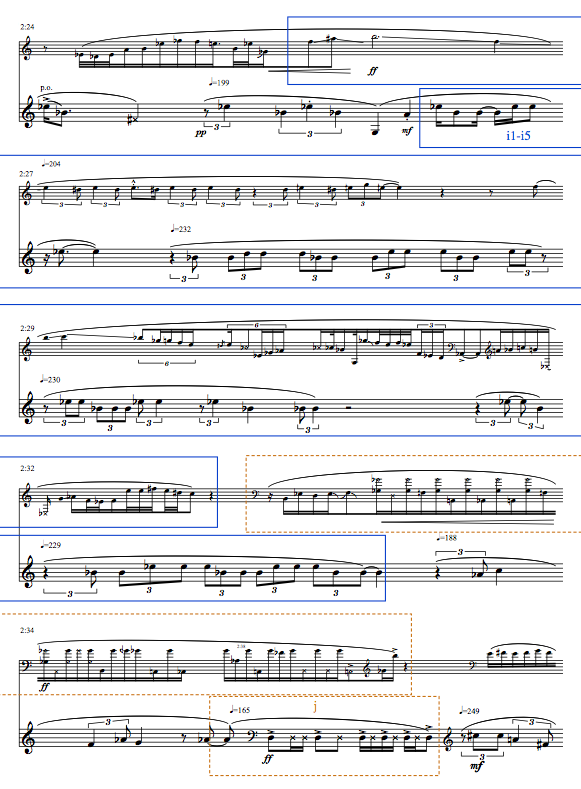

The peak of the tenor solo occurs between 2:15 and 2:40, an excerpt that sees further extensive use of motives in Peacock's playing. Figure 12 demonstrates Peacock's melodic and rhythmic motives, beginning with a rapid (♩≈ 180) triplet-based descending melody interspersed with sixteenth notes (g1). A similar line will occur at 2:33 (g2) and also with a similar tempo (♩≈ 188).

At 2:23 Peacock begins a series of rhythmically accented intervals (h1, h2) characterized by a syncopated second-triplet onset. This motive returns at 2:36 (h3) before evolving into motives i1-i6, a "Morse code" type rhythm that emphasizes the high Bb-Eb perfect fourth pitch interval. The prolonged sequence showcases an extended use of the upper register of the bass, with the Eb in particular being one the highest pitches executed by Peacock thus far in the performance.

Figure 12. Rhythmic and melodic motives, 2:15-2:40

Peacock's phrases also feature variations on a syncopated triplet figure based upon a second triplet onset. Melodies at 2:28 demonstrate triple groupings but initiated on the second 8th note triplet. Phrases i3 and i5 both incorporate this identical syncopated rhythm. The gestures are punctuated by an aggressive fortissimo open D string at 2:35 (j1), articulated with a right hand slap technique. This phrase breaks up the triplet activity with a new and unrelated ♩≈ 165 tempo as well as strong sixteenth note accents. Motive g3 returns to the triplet swing rhythms that began the excerpt, but have been transformed through acceleration in tempo. This transformation continues in motive g4, increasing the tempo further to a rapid ♩≈ 291.

Peacock's motives between 2:15 and 2:40 are clearly influenced by Ayler's dynamics and use of register (Figure 13). As Ayler reaches the register peak of his solo (2:26) Peacock answers with his own use of the upper register, the i1-i5 motives outlined above. In addition to the rhythmic content of these motives, Peacock matches Ayler's extended high register glissando through the active re-articulation of the Bb-Eb dyad. Through this re-articulation (a necessary counter to the quick decay natural to the instrument's higher register), Peacock matches Ayler's gesture through both the extended use of the thumb position and the sustaining of accentuation of pitches.

Figure 13. Climax interaction

The interaction continues with the j1 motive at 2:35. As Ayler suddenly drops from his highest to lowest registers at 2:32 and begins his crescendo through the ff at 2:34, Peacock responds with his own low register fortissimo achieved through the percussive striking of the instrument and a violent snapping of the string against the fingerboard. Ayler's solo fades as Peacock resets the dynamic for the beginning of his improvisation.

This performance is one of many that should help to establish Peacock as one of the most original and unorthodox musicians of the 1960s, the discussion of whom intersects with some of the most compelling issues in modern music. This performance helps to redefine what it is to improvise, reimagining the deeply canonized techniques of time and changes, retaining them as deeply embedded DNA of highly individualized performance. These virtuosic techniques were rich enough by the time of "Ghosts" to become self-sustaining generative structures at the core of new modes of free improvisation.

Independence is the central characteristic of this ability, with phrases manifesting an array of motivic characteristics freely forming an unpredictable network of associations across the first half of the track, and an aggressive interpretation of the swing and broken time traditions. This allows the perception of an extensive world of combinatorial relationships, based upon the biases and inclinations of the listener and performer, which can shift dramatically upon further listening. Because multiple concurrent levels of phrase and motive organization are possible simultaneously, it is difficult to relate the work to analytical traditions rooted in chord/scale theory, rhythmic and phrase hierarchies, or linguistically derived methods of phrase hierarchy, and suggests further work in the fields of interactive analysis.

The independence required to intuit pulse with certainty while executing these motivic shifts suggests Peacock possessed an exceptional rhythmic idiom that was unique in its ability and unfettered in its execution. This approach forms the backbone of Peacock's interpretation, and is characteristic of the gradual emancipation of rhythmic dissonance characteristic to the era. These phrases no longer merely "lay back" or employ mathematically reducible rhythmic subdivisions or tuplets, but rather are a rapid moment-to-moment reevaluation and reinvention of harmony, meter, tempo, grouping, and juxtaposition.

Often an improvisation such as this can challenge the listener's perceptions of the fundamental rhythmic nature of improvisation, but when examined in detail reveal a universe of musical expression that could be called "open" but is not "free" from the materials inherent in more traditional improvisational contexts. Rather, they have been combined and juxtaposed in a flurry of virtuosity that matches the volcanic manner of change that dominated the music and innovators of the decade.

Ayler, Albert. Spiritual Unity. Esp Disk Ltd., 1964. Audio Recording.

Buium, Greg. "Gary Peacock Interview, Pt. 1." Cadence 27 (2001): 9–15. Print.

---. "Gary Peacock Interview, Pt. 2." Cadence 27 (2001): 5–13. Print.

Bley, Paul, and David Lee. Stopping Time. Montreal: Véhicule Press, 1999. Print.

Bley, Paul, and Norman Meehan. Time Will Tell. Berkeley: Berkeley Hills Books, 2003. Print.

Cogswell, Michael. "Melodic Organization in Two Solos by Ornette Coleman." Annual review of jazz studies 7 (1994): 101–144. Print.

Dorham, Kenny. "Albert Ayler: Spiritual Unity." Downbeat 15 (July 1965): 85. Print.

Gridley, Mark C. Jazz Styles: History & Analysis. Upper Saddle River: Prentice Hall, 2006. Print.

Hindemith, Paul. The Craft of Musical Composition: Theoretical Part. New York: Schott, 1970. Print.

Jost, Ekkehard. Free Jazz. Boston: Da Capo Press, 1975. Print.

Litweiler, John. The Freedom Principle. Boston: Da Capo Press, 1990. Print.

Meehan, Norman. "After the Melody: Paul Bley and Jazz Piano After Ornette Coleman." Annual Review of Jazz Studies (2002): 85–116. Print.

---. "Paul Bley's High-Variety Piano Solo on 'Long Ago And Far Away.'" Downbeat 76, no. 3 (2009): 98–99. Print.

Quersin, Benoit. "Les Horizons De Peacock." Jazz Magazine (Jan. 1965): 24–29. Print.

Sabin, Robert. "Gary Peacock: Analysis of Progressive Double Bass 1963-1965." Ph.D. diss., New York University, 2015. Print.

Wilmer, Valerie. As Serious as Your Life. London: Serpent's Tail, 1977. Print.

1 Alternately labeled "free jazz," "avant-garde," and/or "the new thing."

2 Sabin (2015) pp. 417-418.

3 See Wilmer (1977), Jost (1974) as well as Bley and Lee (1999) and Bley and Meehan (2003) for thorough documentation of this era, techniques employed by artists, and cultural critique.

4 Spiritual Unity was recorded one day after Peacock recorded two tracks for the landmark "Individualism" album by Gil Evans, demonstrating the dramatic and diverse nature of the bassist's work from the period.

5 Wilmer (1977) Jost (1974) Gridley (2006), Litweiler (1990).

6 Quersin (1965).

7 Ayler's performance is notated in concert pitch throughout. Further, this paper will deal specifically with the first half of the track and Peacock's concomitant playing with Ayler. For a detailed discussion and analysis of the bass solo see Sabin (2015).

8 See Kenny Dorham's Downbeat review (1965) for an amusing and vitriolic assessment of this recording, including the assessment of Peacock's playing as, amongst other things, "bewildering."

9 As quoted in Quersin (1965) pp. 4-5: "When Albert plays, I play, and I don't know what I play and I'm glad I don't know. In a way it's very impersonal: the emphasis is more on the fact of doing nothing than on doing something. I realize this is probably hard to understand, but it is this absence that gives this music its quality, its life. And it is different from that in bop where it is precisely the presence of certain elements which gives it its quality . . . It is very possible, however, that it will happen in the future as it happened to bop and that it will be precisely the presence of certain elements that will then be fixed that will one day give it its validity."

10 The interpretation of this tempo as actually half, versus a half time feel is a subjective one, and reflects the personal and intuitive nature of the analytical interpretation. The transcription of the complete performance took place over two years, with phrases being modified extensively over time not only due to the lack of referential time keeping by the group but the increasing familiarity with Peacock's idiom. Others are encouraged to transcribe the work for themselves to best confirm or deny the author's findings.

11 Also notable in the a3 motive is the momentary allusion to 4/4-meter, indicated by dotted bar lines. Whereas the constantly shifting tempos of much of the accompaniment prevent the perception of an overt metrical structure, Peacock's line at 1:06 clearly contains a syncopated four-measure phrase. The meter is suggested based upon the number of overall beats, but also the structurally significant double chromatic approach to the high A, which creates the feeling of a 4/4 grouping.

12 See Bley and Meehan (2003) for a detailed discussion of Bley's use of the term "erasure phrase." While not a term that Peacock himself uses to describe his playing (Sabin 2015), the author adapts it here as the effect of Peacock's sudden shifts in content aligns with Bley's definition of the technique, albeit a decidedly conscious one. While Bley describes this technique as the creation of an aggressively jarring and chromatic phrase, often in a differing tempo, so as to obscure the memory of melodic and rhythmic implications of previous lines, Peacock himself has repeatedly described his improvisatory process in this era as purposefully unconscious (Sabin 2015)(Buium 2001).

Robert Sabin is an active bassist, composer, writer, and educator specializing in jazz and contemporary improvised music. He has appeared alongside such artists as Oliver Lake, John Yao-17, Jean-Michel Pilc, Peter Bernstein, Dave Pietro, Dick Oatts, Donny McCaslin, Matt Panayides, Rich Perry, Rich Shemaria, Mark Stanley, Ingrid Jensen, JC Sanford Orchestra, Luis Bonilla, John Riley, Dee Alexander, Aaron Johnson, Kenny Werner, Bruce Arnold, Tony Moreno, Combo Nuvo, Brian Lynch, Onaje Allan Gumbs, Killer Ray Appleton, Victor Lewis, Clarence Penn, Chico O'Farril, Billy Taylor, Vince Mendoza, Roland Hanna, Giacomo Gates, Sandra Bernhard, Bob Mintzer, Dennis Charles, and Ernie Watts. He was awarded Second Place in both the 2001 and 2003 International Society of Bassist's Jazz Competitions. Sabin's third recording, "Humanity Part II" is currently out on the Ranula Music label.

Sabin wrote his Ph.D. dissertation "Gary Peacock: Analysis of Progressive Double Bass 1963-1965" while studying with Peacock from 2009-2014. He is one of the world's leading experts on the bassist and of the early 1960s New York City Avant-Garde.

As an educator, Sabin serves on the Faculty of CUNY in New York City/Hunter College High School, Manhattan School of Music Precollege, and was a founder and director of the Jazz Program at the New York Summer Music Festival and Institute. He has also served on the faculty of New York University, Teachers College/Columbia University, and the Hartwick College Summer Music Festival. He has served as a guest lecturer of theory and ear training at City College, and conducted clinics for the Manhattan School of Music, Jazz at Lincoln Center, and has presented at the International Society of Music Educators biannual conference. He is a New York Pops Teaching Artist, serving as clinician, private instructor, and conductor for high school and college ensembles across New York City.

© 2003 - 2026 International Society of Bassists. All rights reserved.

Items appearing in the OJBR may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the International Society of Bassists, and advance notification of the editors of the OJBR.

Any redistributed form of items published in the OJBR must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in The Online Journal of Bass Research in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] in [MONTH/YEAR], and it is republished here with the written permission of the International Society of Bassists.

Libraries may archive issues of OJBR in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of the OJBR and the International Society of Bassists.

Citations to articles from OJBR should include the URL as found at the beginning of the article and the paragraph number; for example:

Volume 3

Alexandre Ritter, "Franco Petracchi and the Divertimento Concertante Per Contrabbasso E Orchestra by Nino Rota: A Successful Collaboration Between Composer And Performer" Online Journal of Bass Research 3 (2012), <http://www.ojbr.com/volume-3-number-1.asp>, par. 1.2.Volume 2

Shanon P. Zusman, "A Critical Review of Studies in Italian Sacred and Instrumental Music in the 17th Century by Stephen Bonta, Burlington, VT: Ashgate Publishing Co., 2003." Online Journal of Bass Research 2 (2004), <http://www.ojbr.com/volume-2-number-1.asp>, par. 1.2.Volume 1

Michael D. Greenberg, "Perfecting the Storm: The Rise of the Double Bass in France, 1701-1815," Online Journal of Bass Research 1 (2003) <http://www.ojbr.com/volume-1-complete.asp>, par. 1.2.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.