Volume 9 of the OJBR presents Koussevitzky's Double Bass Repertoire: A Reassessment by Andrew Kohn.

Dr. Kohn's comprehensive, detailed, well-documented, and clearly organized research presents an overview and examination of Serge Koussevitzky's double bass repertoire. The study includes works that Koussevitzky composed, works composed by Glière, extant solo bass music, extant chamber music, and transcriptions. The article also surveys compositions that were composed for, but remained unperformed by Koussevitzky.

Much has been written about Koussevitzky's life and career as a conductor, a commissioner of new music, and as a double bass soloist, but not as much scholarship has been published about the repertoire, the actual double bass compositions, that Koussevitzky performed (or may have intended to perform) and the circumstances under which the compositions became part of his repertoire. A significant number of the discussed titles in Koussevitzky's repertoire will be familiar to most performers of classical double bass, but this article offers new and interesting information. For the works that are unfamiliar, this article provides a tangible connection to Koussevitzky, which allows for a gateway to scholarly exploration of otherwise unfamiliar compositions.

This article is different from other articles that have been published to date in OJBR, because this article is an "invited" article. On rare occasions, in order to expedite the publication of outstanding research from recognized scholars, an editor of a scholarly journal can invite an author to contribute an article to the journal.

The author, Dr. Andrew Kohn, enjoys a distinguished performance career and is regarded in the double bass community as one of the leading scholars of the double bass. He is on the faculty of the School of Music at West Virginia University and is a member of the bass section of the Pittsburgh Opera Orchestra and Ballet Theater Orchestras. He holds his Ph.D. from the University of Pittsburgh and received the AD in double bass from the Peabody Conservatory.

Serge Koussevitzky (1874-1951) presided for a quarter of a century at the helm of the Boston Symphony. He established the Berkshire Music Festival. Not content with founding a publishing company dedicated to the new music of the day, he created a foundation through which he commissioned — and which continues to commission — a long and distinguished list of works, including gems of the concert repertoire. He conducted the premieres of many of them himself, along with premiering a host of other works. He mentored many of the leading lights of the next generation of Americans, including Aaron Copland and Leonard Bernstein.1 Any one of these achievements would be enough to win him a permanent place of pride within the annals of music history. And yet, for a certain minority population — that of double bassists — he is even more esteemed as the greatest double bassist of his generation.

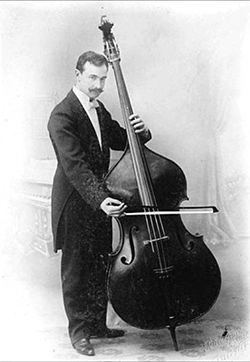

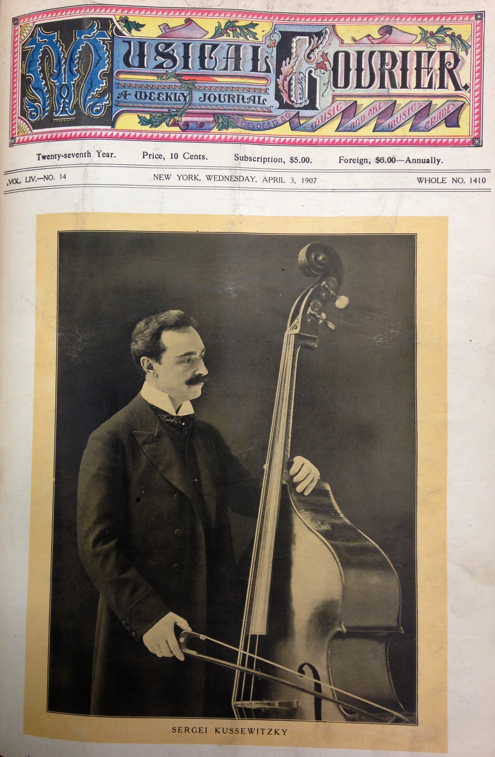

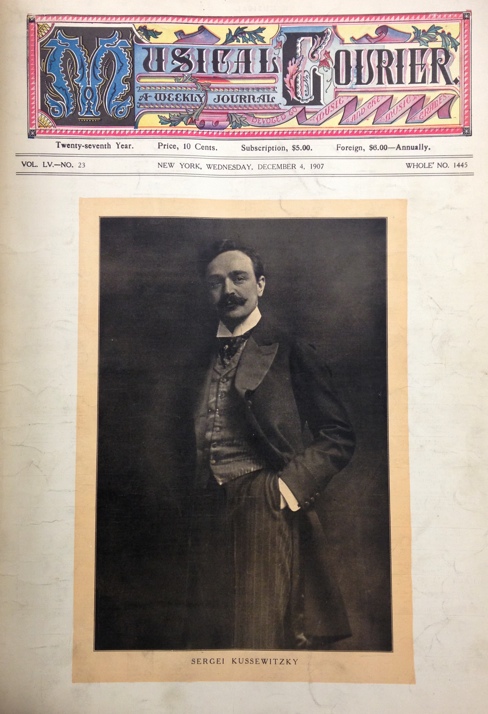

His mastery of the instrument was phenomenal: he took up the instrument at age 14, joined the Bolshoi at age 20, and became principal at age 27. As a soloist, he gave his formal debut in 1898 and formally launched his solo career in 1901, the same year that he assumed the principal post in the Bolshoi. Two years later, in 1903, he gave his foreign debut in Berlin. In another two years, in 1905, he married Natalie Ushkov, daughter of a tea merchant, thereby becoming extremely wealthy. He resigned from the Bolshoi later that year to devote more attention to his solo career, playing recitals and concerti throughout Europe. In 1906 he additionally began studying conducting, moving to Berlin.2 Meanwhile he toured major musical capitals of Europe — Amsterdam, Berlin, Brussels, Budapest, Dresden, Hamburg, Kiev, Leipzig, London, Moscow, Munich, Paris, St. Petersburg, Prague, Stockholm, Vienna, Warsaw — often performing two different programs in a city.3 Unfortunately, despite the large quantity of materials in the Boston Public Library (hereafter, BPL) and the Koussevitzky Archive, Music Division, Library of Congress, including what survives of Koussevitzky's performance material, many scores are missing and few physical copies of his programs have survived, probably due to the conditions under which he left Russia. Consequently, contemporary journals are a major source of information, especially the weekly publication, Music Courier, which was published in New York City from 1880 to 1962. Here we find news nuggets, reviews of individual events, and compilations of excerpts from reviews, from important music centers of Europe. Koussevitzky appeared in items small and large, including being featured twice as cover artist, a very rare achievement (Figures 1 and 2).4 Details are included as an appendix.5 Other periodicals of the period also contribute to a lesser extent. For Russian press I have relied heavily on the Russian-language publications of Astrov and Yuzefovich.

Figure 1: Musical Courier cover featuring Serge Koussevitzky, April 3, 1907

Figure 2: Musical Courier cover featuring Serge Koussevitzky, December 4, 1907

Koussevitzky's two career tracks of established instrumental soloist and budding conductor briefly coexisted: for example, his premiere as conductor, which was with the Berlin Philharmonic, was on Jan. 23, 1908, and his premiere as soloist with Arthur Nikisch and the Gewandhaus Orchestra was the next week on Jan. 29 and 30, 1908. In addition to performing with piano, he also performed with viola d'amore specialist Henri Casadesus, sometimes as a duo, sometimes as a member of la Société des Instruments Anciens, co-founded by Casadesus and Camille Saint-Saëns in 1901.

However, the balance quickly tipped toward conducting: well before he became music director of the Boston Symphony in 1924, the double bass spent most of its time on the back burner. As early as his return to Russia in 1909 he devoted himself almost exclusively to conducting a series of concerts in Moscow and St. Petersburg, along with his famous orchestral tours up and down the Volga in the summers of 1910, 1912, and 1914. Still, his career as a bassist occasionally resurfaced. He soloed with his own orchestra on a few occasions.6 More substantially, in October-November 1916 Koussevitzky made a tour of Russia, giving recitals in Kiev, Rostov-on-Don, Yekaterinburg, Kazan, Kharkov, Tbilisi, and Baku, all of which were then part of the Russian Empire.7 Nor was that his last large resurgence. The Koussevitzkys left Russia in spring 1920, settling in Paris in June 1920. Their final months in Russia were in quarters so insalubrious that Serge reportedly developed the arthritis that soon ended his active career as soloist.8 Nevertheless, in December of 1920 Koussevitzky gave two concerts — one as a conductor and another as a solo bassist — in Rome. He was promptly hired to give a string of 20 recitals in Italy in early 1921, sandwiched between his engagements as guest conductor of the London Symphony Orchestra in January-February and his first self-arranged concerts in Paris in late April, an ambitious schedule recommended by the fact that income from the family's tea empire had been temporarily frozen.9 The tumult of this time of transition is wittily captured by a squib in Musical Courier: "Kussewitzky, who died of starvation in Russia and later was murdered by the Bolskeviki, conducted several concerts recently in London with great success."10

In the midst of 1921, while conducting opera in Barcelona, he cited pain in his left hand as a reason to cancel a concert, which — considering the pace he was then keeping as a performer — is quite significant a decision. Additional performances during Koussevitzky's Paris years, 1920-24, were apparently very few. He did perform two concerti in a concert in Paris on May 19, 1921; a recital planned for London later that summer was mentioned in print; and a performance with la Société des Instruments Anciens on June 13, 1923, was advertised.11

Koussevitzky's final chapter as a performing bassist opened with two solos that he performed when receiving an honorary doctorate at Brown University on Feb. 24, 1926, and continued with three ground-breaking recitals in Boston (Oct. 24, 1927; Oct. 17, 1928; and Oct. 22, 1929).12 During this same period he made the first recordings of double bass solos.13 Never again would he play the bass in public.

These facts are, for the most part, well-known. What, however, did he play? What was Koussevitzky's bass repertoire? A thorough, orderly answer contains several surprises, especially pieces composed for, but never performed by, the master of his era. This detailed examination will allow broader reflections.

• Four Salon Pieces

Andante, op. 1, no. 1

Valse Miniature, op. 1, no. 2

Chanson Triste, op. 2

Humoreske, op. 4.

Although Koussevitzky seems to have performed opp. 1 and 4 more than op. 2, the "Valse Miniature" and the "Chanson Triste" are stronger musically, and today they are more played than the "Andante" and "Humoreske." The wrong notes in the piano part of the "Valse Miniature," mm. 32–38, with their gloomy implications for both Koussevitzky's compositional skills and his concern for publishing detail, are discussed in detail elsewhere.14

• Concerto (mostly by Reinhold Glière), op. 3. This widely-performed work is generally considered one of the four most important concerti in the bass repertoire.15 The attribution to Glière is discussed in detail elsewhere, along with its source material and its many editions and editorial problems.16 Here, suffice it to say that the piece is, apart from its opening cadenza, uncannily similar to earlier works by Glière, and that the dimensions of this op. 3 would be an enormous stretch for the composer of Koussevitzky's undisputed opp. 1 & 2.

Koussevitzky premiered the piece in Moscow on Feb. 25, 1905; thereafter, he seems to have favored performances with piano accompaniment.17 In addition to Koussevitzky's many performances of the complete concerto in recital, the slow movement seems to have been a recital favorite of Koussevitzky: he performed it at Brown and subsequently recorded it.

• Three etudes. Koussevitzky never performed these brief unaccompanied essays; they are included here to complete the double bass portion of Koussevitzky's slight works list. For discussion, see Stiles, Compositions, 59-67, including his plausible proposal that they were composed as sight-reading for auditions.18 The manuscripts are in the Library of Congress; Stiles reproduces them, along with his own analysis of their content, 86-101.

• Reinhold Glière, Four Pieces.

Intermezzo, op. 9, no. 1

Tarentella, op. 9, no. 2

Präludium, op. 32, no. 1

Scherzo, op. 32, no. 2.

The dedication, although missing from modern editions, is included in the first editions and numerous secondary sources.19 Glière and Koussevitzky enjoyed a very close relationship at the time, arguably peaking in Koussevitzky's premiere of Glière's Second Symphony with the Berlin Philharmonic on Jan. 23, 1908. That is, in 1902 Glière composed a pair of pieces as a vehicle for a young virtuoso, just starting out, and composed another pair in 1908 as — perhaps — a thank-you for a very high profile performance. According to the surviving records, despite his numerous performances of the Intermezzo and the Tarantella separately, Koussevitzky never performed op. 9 as a pair and never performed op. 32 at all.

These pieces are among the gems of the bass's concert repertoire. When the four pieces are performed as a set, op. 32 is performed first. What could follow the Tarentella, a real barn-burner? Indeed, when Koussevitzky played a pair of recitals, the Glière Tarantella closed one recital and the Bottesini Tarantella (discussed below) closed the other.

• Giovanni Bottesini, Grand Duo Concertante. Although we have no clear record of a public performance, Arthur Abell, in previewing Koussevitzky's New York recital of 1928, recalled hearing this piece played privately by Koussevitzky, violinist Jacques Thibaud and, at the piano, Fritz Kreisler.20 This is corroborated, or at least echoed, by an unpublished document that survives in the Library of Congress, referencing "the duet for voilin [sic] and double bass y [sic] Bottesini."21 This anonymous Chapter 9, comprising pp. 116-31, records Koussevitzky addressing the author as "Arthur" — probably also by Abell, then, and probably from his unpublished memoirs.22

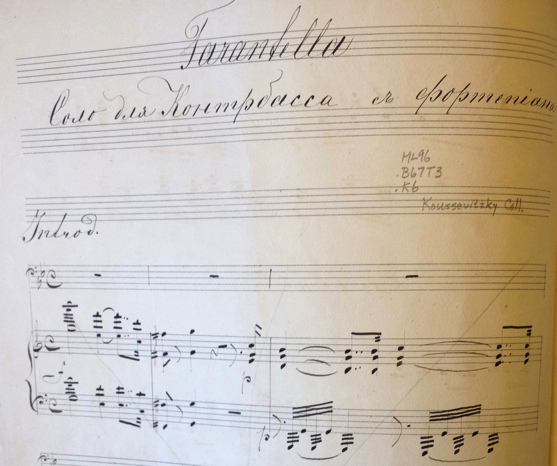

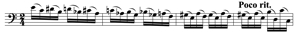

• Bottesini, Tarentella. One of the most popular of Bottesini's works for bass and piano, Koussevitzky's hand-written performance material for this piece is in BPL (Figure 3). He performed the piece in his early career in Russia, at his Berlin debut in 1903, and frequently thereafter.

Figure 3: Koussevitzky's copy of Bottesini, "Tarentella," opening (BPL)

• Bottesini, Fantasia "la Sonnambula." Arguably the best of Bottesini's seven pot-pourris, Koussevitzky first performed this piece in Berlin in 1907 and repeated it elsewhere afterwards. His performance material has not survived.

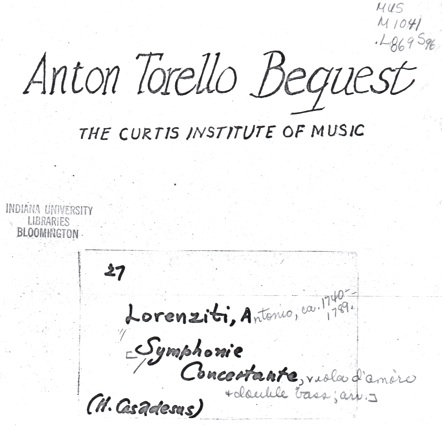

• Henri Casadesus ("Lorenziti"), Sinfonia Concertante. As he did so often, Casadesus ascribed this composition to another composer from an earlier era: in this case, a certain Lorenziti — citations sometimes name Antonio [Joseph Antoine, c1740-89], sometimes his brother, Bernardo [Bernard, after 1749-after 1815]. Koussevitzky's solo parts in C and D (that is, for both the orchestral tuning of G, D, A, E and the common solo scordatura of A, E, B, F-sharp) are in BPL and reproduced in Stiles, Compositions, 144-60. Citations of early performances include Astrov, who cites a performance in the home and presence of Tolstoy in 1910, and Stoll, who cites the performance with the Berlin Philharmonic under Arthur Nikisch in 1911.23 The piece was brand new, since the online catalog of the Bibliothèque nationale de France gives the work a date of 1910; a review cites a performance of the cadenza alone as early as 1909.24 Koussevitzky later performed the work with Casadesus in Paris in 1921 and (perhaps) 1923, as well as in the Boston recital of 1928. A hand-written copy of the piano score, (Figure 4), which makes it crystal clear that "Lorenziti" is actually Casadesus, is preserved in Anton Torello's papers in the library of the Curtis Institute (with a Xerox copy at Indiana University). Casadesus' manuscripts, including this piece, are in the Bibliothèque Nationale in Paris.

Torello is a major figure in American double bass history, having served both as principal bassist of the Philadelphia Orchestra and as the first professor of double bass at the Curtis Institute. He performed the work, along with concertmaster Thaddeus Rich and the Philadelphia Orchestra, conducted by Leopold Stokowski, on Feb. 27 and 28, 1920. A modern performance was given at the 1998 convention of the international viola d'amore society; another was given by the Wandsbeker Symphonie Orchester in 1999; another, with piano reduction, is available via YouTube, performed by the duo "Sweet 17."25

Figure 4: Casadesus, cover from Symphonie Concertante, attr. Lorenziti, with piano reduction by Torello (from copy at Indiana University)

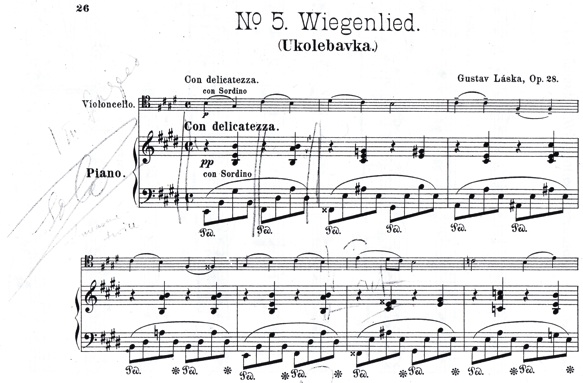

• Gustav Láska, Berceuse. Czech double bassist Gustav Láska (1847-1928) composed a set of five pieces, op. 28, for bass and piano: "Idylle," Ländler," "Fantasie Impromptu," "Masurek," and "Ukolébavka." The fifth is Koussevitzky's piece, variously translated as "Berceuse," "Cradle Song," and "Wiegenlied." This should not be confused with Láska's additional piece without opus number for bass and piano, "Schlummerlied." As an additional complication, Láska arranged another "Wiegenlied," composed by Michael Hauser, for bass with quartet accompaniment, op. 11, no. 2.26 Koussevitzky's personal copy is in BPL, an edition of 1892 by Breitkopf & Härtel, (Figure 5). The other movements have no markings, suggesting that they were never performed. It is an odd quirk that Koussevitzky's personal copy is not of the original version for bass and piano, but rather the transcription for cello and piano.

Figure 5: Koussevitzky's copy of Láska, "Wiegenlied," opening (BPL)

• Franz Simandl, Concerto. Astrov (20) cites a performance of this piece on June 22, 1899. According to a review in Musical Courier, Koussevitzky also included this work in his second Berlin recital of 1907 (as noted, he often remained in a city long enough to perform two different recital programs).27 It is a weak piece, rather like a pot-pourri of Simandl's famous etudes. It is unlikely that the citation is a garbled reference to Simandl's transcription of the Handel Oboe Concerto in G minor (discussed below), since the recital programs provided sparing information and excluded such information as editors and transcribers. In any event, the Simandl Concerto did not remain a part of Koussevitzky's performing repertoire. No performance material has survived.

• Eduard Stein, Concertstück. This work was published under the aegis of Franz Simandl, but separately from his famous and influential series, the Hohe Schule (discussed below). Now rarely performed, the piece was very important in Koussevitzky's career. With this work, in 1894, Koussevitzky won a position in the Mariinsky Theater — a position he declined — as well as the position he held for the next decade in the Bolshoi Theater. Koussevitzky's later performances of the piece are repeatedly documented in Musical Courier, including in Leipzig, Vienna, Paris, and Berlin, demonstrating the importance of this repertoire item in his early career. The original publication is now quite rare, but a reprint, on smaller paper and with light editing by Frederick Zimmermann, is widely available, published by International Music Company (1957). Despite the dates added to this reprint — that is, "(1701-1775)" — the composer is the Eduard Stein who lived from 1818 to 1864, who studied with Weinlig and Mendelssohn in Leipzig, and who directed the "Loh Concerts" in Schwarzburg-Sondershausen beginning in 1853; the Concertstück was premiered at a Loh Concert on September 17, 1854.28

• Henri Casadesus ("Luigi Borghi"), Sonata no. 3 for viola d'amore and bass. Casadesus performed this work as early as the end of 1905, joined by Édouard Nanny, in concerts of the Sociéte de Concerts des Instruments anciens.29 Koussevitzky performed this piece repeatedly with Casadesus, including in several venues between 1907 and 1909, in Paris in 1921 (and perhaps 1923), and in Boston in 1928.30 Koussevitzky's bass part is in BPL and is reproduced in Stiles, Compositions, 161-63.

Although the real Luigi Borghi wrote an undisputed work for viola d'amore and double bass (known as Sonata no. 1),31 and although the manuscript attributes this Sonata no. 3 to Borghi, there can be no doubt that this is another composition by Henri Casadesus, as others have noted.32 This is particularly believable in light of how many of Henri Casadesus's compositions he attributed to Borghi (second only to Lorenziti in number of his misattributions). This sonata is, therefore, another of Casadesus's spuriosities (to use a word from Cudworth) — albeit a better stylistic imitation of its model than many such.33 This assessment is based solely on the bass parts and on reviews of performances: sadly, there seems to be no surviving copy of the viola d'amore part.

• Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, "Per Questa Bella Mano," K. 612. This concert aria for basso, string bass obbligato, and orchestra is one of the brightest gems of the bass repertoire. Koussevitzky included it in his Boston recital of Oct. 22, 1929. Intended for what is called "Viennese third-fourth" tuning (from top to bottom, A, F-sharp, D, A, and often a fifth string of variable pitch, most often F-natural), the piece is extremely demanding when played on an instrument tuned entirely in fourths, which has given rise to a range of editions. More recently, players are increasingly recovering the original tuning. Koussevitzky's solo part, using the standard solo tuning of A-E-B-F# and transposed from the original key of D into C, along with his copy of the vocal part, are in BPL; they are reproduced in Stiles, Compositions, 164-72. As noted in the review of Koussevitzky's 1908 premiere with the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra, "Per Questa" was (erroneously) believed to have been unperformed since Mozart's death, lending special emphasis to Koussevitzky's later revival of the work.34

• Franz Schubert, Piano Quintet in A Major ("Trout"), D. 667. This, the most famous chamber composition in the bassist's repertoire, needs no discussion here. Koussevitzky included the variations and finale from this work in his first Boston recital.

• J.S. Bach: Aria (from Cantata 12, "Weinen, Klagen, Sorgen, Zagen"). Arthur Lourié (37) provides an important list of eight transcriptions from which most of this section is drawn, with this work as the first alphabetically. However, no trace of this transcription has survived.35 It's a confusing ascription. If indeed Koussevitzky played an aria from this Cantata, which one? The six movements of the Cantata include an opening Sinfonia and two choruses; these choruses frame the three central arias. The alto aria, "Kreuz und Krone sind verbunden," requires an obbligato oboe. The basso aria, "Ich folge Christo nach," lasting little more than two minutes, is quite brief to be performed as an independent item. The tenor aria, "Sei getreu," requires an obbligato trumpet playing the chorale melody "Jesu, meine Freude." In fact, the most likely candidate would be none of the arias, but rather the Sinfonia, widely played as an oboe solo with piano accompaniment. Such an error would also be parallel to referring to Scriabin's Etudes as Preludes (discussed below).

Given this uncertainty, it is also possible that Lourié inaccurately referred to another work by Bach. One likely suspect would be the Air from the Orchestral Suite no. 3, already famous in Koussevitzky's day as August Wilhelmj's transcription "Air on the G String" and available in a further transcription by Franz Simandl.36 This would however assume Lourié turned "Air" into the Italian "Aria." Could it be the Arioso from Cantata 156, widely played as a transcription for cello and piano, with a different twist of title? Since the first publication of this transcription appears to be that of Sam Franko (G. Schirmer, 1915), this would be a bit late in the game to be a regular item in Koussevitzky's repertoire. Even if he included it in his Russian programs of 1917-20, getting sheet music from the U.S. during World War I and the Russian Revolution would be quite a challenge. Another possibility is the famous aria "Schlummert ein" from Cantata 82 which, in addition to having an identical title of "Aria" rather than the variants of "Air" or "Arioso," holds out the additional connection that "82" could easily be misread as "12." Moreover, this Aria was included in a volume edited by Ebenezer Prout and published by Augener in 1909, so Koussevitzky had ready, timely access to material that could rather easily be converted for his purposes. Since we have neither any copy of the transcription nor any program that lists the work, we can only speculate.

• Ludwig van Beethoven, Minuet in G, WoO 10, no. 2. Koussevitzky's manuscript piano score, with performance notations, is in BPL (Figure 6). He included this piece in his Italian tour of 1920-21 as well as recording it.

Figure 6: Koussevitzky's copy of Beethoven, Menuett, opening (BPL)

• Max Bruch, Kol Nidrei. Koussevitzky's manuscript piano score is in the Library of Congress and is reproduced in Stiles, Compositions, 105-16. While most modern bassists perform the piece in the original key of D minor, Koussevitzky's performances, which began in Russia, continued in Berlin in 1903, and were repeated extensively thereafter, were in A minor.37 Despite the change of keys and the resultant need for a transposed accompaniment, he performed the work both with piano and with orchestra. The orchestral material has not been located.

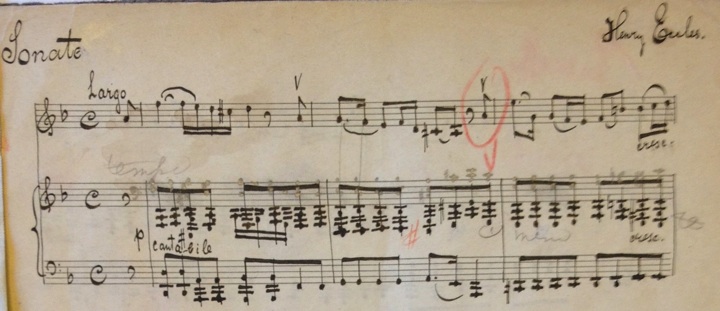

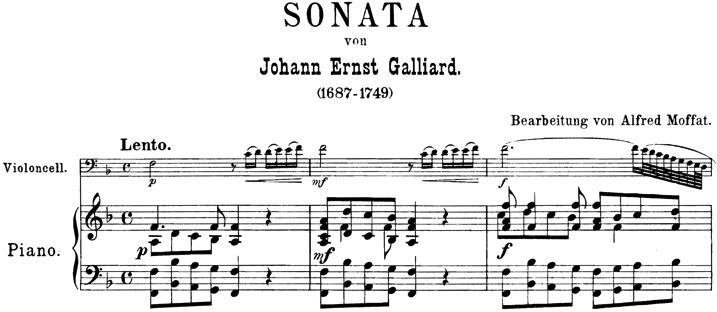

• Henry Eccles, Sonata no. 11. Koussevitzky performed at least the opening movement of this sonata in his Italian tour of 1920-21. The manuscript piano score, which is a transposition of Alfred Moffat's edition for cello and piano in order to accommodate solo scordatura, is in BPL (Figure 7). Moffat's edition (Figure 8), is still in widespread use, and is also the basis for the editions for various instruments published by International Music Company, which is what most modern bassists use. All four movements of Koussevitzky's manuscript show performance indications. Koussevitzky recorded the first movement; although the 78s included only one take, two takes are available on the Biddulph CD.

The sonata has a colorful history. Although it is often published independently, it is in fact the 11th of a set of 12, published in Paris in 1720. Concerning this set, Andreas Moser exclaimed, "This volume represents the most audacious forgery that I have ever yet encountered. ...not less than eighteen movements originated not with Eccles, but were taken note for note, measure for measure, from beginning to end from the 'Allettamenti' [op. 8] of Giuseppe Valentini!"38 Though Sonata 11 contains no Valentini, its second movement plagiarizes F.A. Bonporti's Invenzioni op.10, no. 4, mvt. 4.39

This piece illustrates a common strategy in Koussevitzky's transcriptions: reading the original part with a change of clef. In this case, the tenor clef of the cello part is read in bass clef: that is, in c minor. The scordatura transposed the result to d minor. The Bruch can be performed the same way. Another strategy is used in pieces including the Galliard sonata, discussed next.

Figure 7: Koussevitzky's copy of Eccles Sonata, opening (BPL)

Figure 8: Opening of Eccles Sonata, ed. Moffat

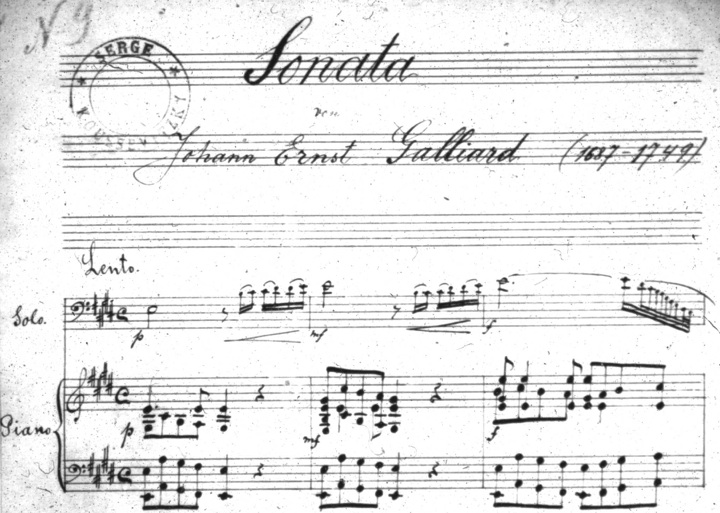

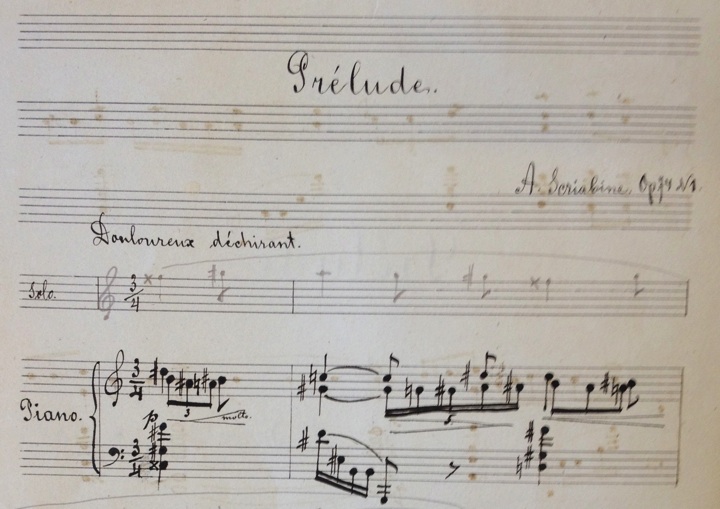

• John Ernest Galliard, Sonata. Koussevitzky included the opening movement of this sonata in his Italian tour of 1920-21.40 The manuscript piano score is in BPL (Figure 9). It transposes a composite sonata published by Alfred Moffat in 1904 (Figure 10) from F down to E (the bass playing in D, with solo scordatura). Moffatt drew from two sets of cello sonatas, substituting the third movement of a sonata published in 1746 within a sonata otherwise published in 1733. He probably considered the original third movement, which is little more than a brief recitativo, insufficient. Frederick Zimmermann's International Music Company edition of 1949, the usual source for modern bassists, retains Moffatt's substitution.

Koussevitzky transposed the piece by a mere semitone to a much more comfortable key for the bass, as he did also with the Mozart Concerto and (I argue later) the Handel sonata. The Rachmaninoff Vocalise is transposed by a whole step, from c-sharp minor to b minor.

Figure 9: Koussevitzky's edition of Galliard Sonata, opening (BPL)

Figure 10: Galliard Sonata, ed. Moffat, opening

• George F. Handel, Sonata in F-sharp (for violin). Although one might suspect that this work is an inaccurate citation of the Handel Oboe Concerto that Koussevitzky more often played, this is a distinct transcription, included in recitals as early as 1903; reviews specify that is was originally for violin.41 But which Handel sonata is it? Since Handel wrote no sonatas in this key, Koussevitzky must have played a transposition. Alas, no trace of the score remains. However, we can at least consider the possibilities.

The program of Feb. 12 1907 lists the movements as Adagio, Allegro, Largo, Allegro, which reduces the options considerably.42 The most likely possibility would be the (spurious) Sonata in F, HWV 370, a popular piece that lies rather well when transposed in a manner parallel to Koussevitzky's version of the Galliard Sonata. Other violin sonatas that have this order of movements, and which are therefore potential candidates, include the (spurious) Sonata in A, HWV 372 and the (spurious) Sonata in E, HWV 373. (Of course Koussevitzky would not have known that later scholarship would prove each of these sonatas to be misattributed; he thought he was performing genuine Handel.) The Flute Sonata in B minor, HWV 376, also has the requisite order of movements, but it seems unlikely the concert reviewers would have repeatedly called it a violin sonata.

• Handel, Oboe Concerto in G Minor, HWV 287 (ca. 1704-5). This transcription is drawn from Franz Simandl's famed Hohe Schule series, a nine-volume set of original compositions and transcriptions with which Simandl completed his published course of training for the double bassist: a core solo repertoire for the bass. The bassists who served as composers and editors for the series were among the most distinguished in the world. A rich resource for bassists of that period, it has been in use ever since, albeit often in other publishers' reprints and new editions. More recently yet, the entire historic series, long out of print, has been reissued in 2014-15 by the original publisher, previously known as C. F. Schmidt, now known as CEFES.

Koussevitzky's copy of this piece is housed in BPL and is rich with performance indications. A card tipped into this copy and tacitly referencing Smith (20) indicates that this is the work he performed in Moscow in 1904; The Musical Courier and other sources demonstrate that he performed it often, both with orchestra and with piano. He also was known to perform the third movement, the Sarabande, as a separate number: specifically, on receiving his honorary doctorate at Brown University in 1926.

Koussevitzky owned the entire 4th volume of the Hohe Schule (comprising six works under individual covers), from which he also performed the Lvovsky and perhaps performed the Hegner, each listed below. It is surprising, given his obvious preference for works by famous composers, that Koussevitzky apparently did not explore Simandl's 6th volume, which includes transcriptions of works by Bach, Beethoven, Mendelssohn, and Mozart — the one possible exception being if the Bach "Aria" listed above is actually Simandl's transcription.

• Handel, Largo ["Ombra Mai Fu" from Serse]. This famous and widely transcribed piece was included, accompanied by piano in an arrangement attributed in the program to Koussevitzky, in his Italian tour of 1921.43 Although no performance material has apparently survived, he might have used the transcription by the Stuttgart court musician Hans Wolf, published by C.F. Schmidt (Figure 11).44

Figure 11: Handel Largo, solo part, opening

• Bretislav Lvovsky, "Drei Stücke nach Corelli." This is an item from Simandl's Hohe Schule series, volume 1. Lvovsky (1857-1910) studied with Simandl and later joined the Vienna Court Opera. Although Koussevitzky did not perform this piece often, Musical Courier cites a performance in Berlin in 1903.45 Lvovsky's three movements comprise Corelli's op. 5 no. 8, mvts. 1 ("Preludio: Largo") and 3 ("Sarabanda") followed by opus 5 no. 9, mvt. 4 ("Tempo di Gavotta"), all transposed such that the bass plays in C, using solo tuning. The piano accompaniment is therefore in D. The solo bass part of the "Tempo di Gavotta" alternates between Corelli's basso continuo line and a rewriting of the violin line in parts of the second section of this binary form. The Lvovsky is the presumptive source of Oscar Zimmerman's revision of this edition in his widely-used Seven Baroque Sonatas (Rochester: Zimmerman, 1977). Koussevitzky's copy has not been located.

• Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart, Bassoon Concerto, K. 191. The score, with piano reduction and with performance indications, is in BPL (Figure 12). Koussevitzky performed this often, both with orchestra and with piano, including in Leipzig in 1908, in Moscow and St. Petersburg during the 1909-10 and 1916-17 seasons, in Berlin in 1911, in his Italian tour of 1921, and in Paris in 1921.

Figure 12: Koussevitzky's edition of Mozart Concerto, opening (BPL)

• Sergei Rachmaninoff, "Vocalise," op. 34, no. 4. Koussevitzky's manuscript piano score is in the Library of Congress and reproduced in Stiles, Compositions, 117-21. The piece is transposed to B minor. Some bassists have entertained the notion that Rachmaninoff composed the piece for the bass and later rewrote it as a Vocalise, a tale widely disseminated by Gary Karr. The fullest exposition of this story is in Stiles, 68-69, including the incredible claim that the Library of Congress lost a page of Rachmaninoff's manuscript. The Musical Courier review of the premiere clears up this misconception. In April 1916 the Moscow correspondent, Ellen von Tideböhl, reviewed recent concerts in Russia, including Koussevitzky's concert series. She reported that . . .

Mme. Neshdanowa . . . at Kussewitzki's sixth symphony concert . . . sang the 'Vocalise' . . . with the composer himself at the piano. Kussewitzki transcribed the 'Vocalise' for his contrabass and performed it at his fourth symphony concert, so that we heard it before it had been sung by Mme. Neshdanowa."

She adds that . . .

. . . the performances of both artists were admirable alike in their breadth and subtlety. The beauty of Kussewitzki's phrasing was especially note-worthy in the slower movements, and the whole reading was one of rare merit. One would scarcely believe that the big instrument could realize such soft and delicate sounds!46

The still-unstable transliteration from the Cyrillic of Koussevitzky's name is also visible in the same review article's citation of a young violin virtuoso, the 15-year-old "Yasha Heyfetz."47 It was not until the announcement of his appointment to the Boston Symphony Orchestra, made in Vol. 88, no. 17 (April 24, 1924) that The Music Courier settled decisively on the spelling of Serge Koussevitzky.

In brief, then, Koussevitzky transcribed the piece and performed his transcription before the original vocal version was premiered. Although the piece has a long and illustrious history as a bass transcription, a transcription it remains.

• Maurice Ravel, "Vocalise-étude en Forme de Habenera" (1907, pub. 1909), widely transcribed as "Pièce en Forme de Habañera." Although Burghausen and Stiles list this transcription, no trace of it seems to have survived. Unusually, Stiles provides no source for his ascription; Burghausen's earlier article is, of course, an obvious candidate.

• Camille Saint-Saëns, Cello Concerto no. 1. Although the large leap in difficulty between Koussevitzky's other repertoire and this work could make the performance seem fanciful, he did indeed perform this work in Leipzig in 1906, as confirmed by a contemporary review in the semimonthly, Die Musik.48 Smith (p. 31) explains that the performance in Leipzig, an "extraordinary stunt," was with a pick-up orchestra. Yuzefovich cites Koussevitzky practicing the piece while still a student with cellist friend Vladimir Dubinsky, which suggests that this performance had a long gestation period.49 The piece has recently been performed in international venues by bassist Catalin Rotaru to great acclaim. Koussevitzky's performance material has not survived.

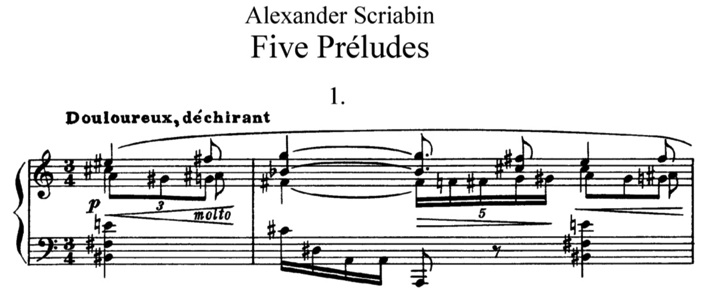

• Alexander Scriabin, Two Preludes, op. 74, nos. 1, 2. These are the works listed as "Two Etudes" by Lourié, a change in title repeated by Olga Koussevitzky and by Stiles.50 The manuscripts are in BPL (Figure 13). The copies are very clean and have the piano part in ink, the solo part in pencil, giving rise to the question whether Koussevitzky ever got around to performing these preludes. However, we have no program from Koussevitzky's Russian tour of 1916, in which this work would have been a fitting commemoration of Scriabin's death the previous year: indeed, the second Prelude was the final piece Scriabin completed. The pieces are transposed up a step, with important lines given over to the solo bass, as seen by comparison with the published score (Figure 14). Given the usual solo bass scordatura, this allows the bass to read what were the original printed pitches. Given the date of composition, Lourié is making a broad generality when he attributes Koussevitky's eight transcriptions, including this piece, to "c. 1900."

Figure 13: Koussevitzky's edition of Scriabin, Prelude 1, opening (BPL)

Figure 14: Scriabin, Prelude 1, opening, published

• Richard Strauss, Sonata in F, op. 6 (transcribed from the 1883 cello sonata). Although Lourié lists this transcription, no trace of it seems to have survived. For a performance on bass, see Michael Klinghoffer's CD, "Mostly Transcriptions, Vol. 2."51

• Peter Illych Tchaikovsky, Andante Cantabile (1872). Smith (11) tells us that Koussevitzky played this famed movement from Tchaikovsky's first string quartet in Tchaikovsky's rooms with the composer at the piano in 1892, when the bassist was but 18 — that is, the year before Tchaikovsky's death. However, in the absence of Koussevitzky's performance materials, the key and edition remain an open question. There are at least four contenders.

Although Smith describes the performance material as Koussevitzky's arrangement, it should be noted that cellist Wilhelm Fitzenhagen transcribed the piece for cello and piano, and Tchaikovsky himself transcribed the piece for cello and string orchestra in 1888.52 Both transcriptions transpose the movement from B-flat to B. To further complicate things, Koussevitzky's professor, Joseph Ramboušek (1845 - 1901) also published a transcription for bass and piano in the key of C (Moscow: P. Jurgenson, [n.d.]). It is therefore possible that Koussevitzky played the cello part of Fitzenhagen's or Tchaikovsky's edition on the bass, or played Ramboušek's transcription. However, it seems most likely that Koussevitzky used Fitzenhagen's edition: Tchaikovsky liked it well enough that he not only took up the idea of a version for solo cello, producing his own arrangement with string orchestra, but when he did so he retained both Fitzenhagen's key change to B and Fitzenhagen's revisions to the bowing.53 Since they are so similar, wouldn't Tchaikovsky have preferred the convenience of reading a piano part over reducing even a well-known score at sight? Fitzenhagen's accompaniment is also similar to the orchestral version, especially in that he lowers the original bass line by an octave in almost all of mm. 1-49 and 98-121. Ramboušek does not, which simplifies balance but, since his solo line often drops below the bass line, Ramboušek inverts Tchaikovsky's harmony, rendering his edition a poor choice to place on the composer's music rack. Finally, even if Ramboušek's version was available in 1892, which is not certain, it is difficult to imagine a teenager approaching such a revered composer with such a beloved work, bearing either his own student effort or his teacher's transcription into yet another key.

Certain other transcriptions seem less likely to have been performed by Koussevitzky. These include items listed in previous secondary documents but that are otherwise undocumented, as well as music that Koussevitzky owned, now in BPL and the Library of Congress, that bear no indications of use and for which we have no record of performance. This list therefore can be seen as a combination of unconfirmed citations and a supplementary catalog of Koussevitzky's personal library of solo bass music, including many presentation copies. Technical studies such as etudes, some of which are in BPL, are not included here.

• Ludwig van Beethoven, variations on "Bei Männern" and "Judas Makkabäus." Although Koussevitzky's copies are in BPL, they are completely clean of any marking, suggesting that they were never used.

• Vincenzo Bellini, Fantasy. Although Stiles, on the strength of an email from Yuzefovich, includes this piece, no such piece apparently exists. This presumably refers to Bottesini's "Fantasia 'La Sonnambula'," after Bellini's opera, a known item of Koussevitzky's repertoire.

• Frédéric Chopin, Nocturne, op. 9, no. 2 (transcribed by Franz Simandl). This is another of the works from Simandl's Hohe Schule, vol. 4. Koussevitzky's copy, in BPL, is completely clean of any marking, suggesting it was never used.

• Franz Joseph Haydn, Cello Concerto no. 1, Hob. VIIb:1. No trace of this transcription, listed by Smith, has survived. It is possible that Smith spoke with Vladimir Dubinsky who, as noted in the discussion of the Saint-Saëns concerto, recalled in print that he and Koussevitzky practiced unspecified cello concerti together. But perhaps he meant the Hegner transcription that follows?

• Ludvig Hegner, "Andante con Variazioni." Franz Simandl published this transcription of the slow movement of Haydn's "Surprise" Symphony, produced by his former student Hegner, who was by this point the solo bassist in Copenhagen's Royal Theater Orchestra, as part of the Hohe Schule, vol. 4.54 Koussevitzky's copy, in BPL, is completely clean of any marking, suggesting it was never used. However, it is possible that this is the piece identified by Smith as the Haydn Cello Concerto.

• Max Henning, Romanze, op. 107 (1936). This rarity was composed for a high-tuned bass (top to bottom: C-G-D-A) and organ. Koussevitzky's copy in BPL appears never to have been used. By 1936 Koussevitzky had long given up performing in public.

• Nestor Higuet, Fantasie (1936). This work was a Morceau de Concert at the Paris Conservatory. The score bears a dedication to Édouard Nanny, the bass professor in Paris; Higuet was a composition professor in Brussels. Again, by 1936 Koussevitzky had given up performing in public. His copy in BPL is completely clean of any marking, suggesting it was never used.

• Werner Josten, Canzona Seria for low strings (1940). Josten (1885-1963), born in Germany, emigrated to the U.S. in 1920 or 1921 and taught at Smith College. Scored for Viola I & II, Cello I & II and Contra-Bass, the divisi of gli altri celli in mm. 202-3 (out of 273) and the indications that mm. 203-36 is for four solo players show that this is an orchestral work. This is a presentation copy.55

• Filip Lazăr, "Bagatelle" (Universal, 1925).56 An important Romanian composer and pianist of his generation, Lazăr (1894-1936) dedicated this piece to Joseph Prunner (1886-1969), the great Austrian bassist who taught in Bucharest in the early 20th century. The copy in BPL is presumably, therefore, a presentation copy.

• Adolf Míšek, Sonatas. Míšek (1875-1955) studied with Simandl, succeeded him as professor at the Vienna Conservatory, and moved to Prague after World War II. The BPL holds copies of the publications of Sonatas 1 and 2 (composed 1905, published in 1909 and 1910, respectively), specifically identified as presentation copies given to Alois Vondrák (a bassist in the Boston Symphony, 1925-1940), and a manuscript copy of the 3rd Sonata. These sonatas by an important Czech bassist have all become staples of the bass repertoire. However, even if Vondrák immediately gifted them to Koussevitzky upon arrival in Boston, Koussevitzky did not include them in his subsequent recitals.

• Adolf Moissl, Konzert-Stück. Moissl studied alongside Simandl with Josef Hrabě in Prague and later worked in Wiesbaden. Koussevitzky's copy of this work, part of Simandl's Hohe Schule, Vol. 4, included in BPL, is completely clean and apparently was never used.

• Herman Sandby, "Solostykke" (1944). This lovely piece by the former solo cellist of the Philadelphia Orchestra, included in BPL but composed well after Koussevitzky ceased performing as a bassist and devoid of any indications of use, is surely a presentation copy given when the piece was published by Wilhelm Hansen.

• Karoly Trautsch, Moment de Valse. Trautsch (1830-1910) was another Hrabě student; he later worked in Budapest. Koussevitzky's copy of this work, part of Simandl's Hohe Schule, Vol. 4, included in BPL, is completely clean and apparently was never used.

Before proceeding to the final group of pieces, we can take stock of the music that we know Koussevitzky performed. This repertoire can also be arranged chronologically by performance, showing the growth of Koussevitzky's confirmed repertoire.

Even at the beginning of his career, Koussevitzky built a core repertoire that he drew upon for the rest of his career. In 1896 he performed the Stein Concertstück and the Bottesini Tarantella; in 1901 he performed Bruch's Kol Nidrei and his own "Valse Miniature;" in 1902 he performed the Handel Sonata and his own "Andante."57

The record becomes more complete after his international debut. In 1903-4 Koussevitzky performed all of his previous repertoire except the Tchaikovsky, filling out the programs with the Handel concerto, Láska, and Lvovsky:

Bottesini, Tarentella

Bruch, Kol Nidrei

Handel, Violin Sonata in F-sharp minor and Oboe Concerto

Koussevitzky, two of his four salon pieces (the "Valse Miniature" and an unnamed piece: presumably the "Andante")

Láska, Berceuse

Lvovsky, Drei Stücke nach Corelli

Stein, Concertstück.

By modern standards, this is one overstuffed recital, with about 72 minutes of playing time.58 This material was extended to fill two programs by the inclusion of a few pieces for solo piano, performed by the collaborative pianist, on each program.

By the 1906-7 season, he added:

Borghi [Casadesus], Sonata 3

Bottesini, Fantasia "La Sonnambula"

Glière, Intermezzo and Tarentella

Koussevitzky, Concerto

That is, by modern standards, another recital program.

Thereafter, only a few pieces were added to his regular repertoire: by October, 1907 he added the Mozart Bassoon Concerto; 1909 marks the first documented performance of his own "Chanson Triste"; in 1910 he added the Casadesus Sinfonia Concertante; in 1915 he added the Rachmaninoff Vocalise; by 1920 he added the Eccles Sonata, the Galliard Sonata, and the Handel Largo. This is a conservative list, since we are missing such important information as the content of his 1916 recital tour of Russia.

Less often, apparently, he performed:

Bach, Aria (no documented performance)

Bottesini, Grand Duo Concertante (in private, while living in Berlin)

Mozart, "Per Questa Bella Mano" (in 1929)

Schubert, two movements from the "Trout" Quintet (in 1927)

Scriabin, Two Preludes (no documented performance)

Tchaikovsky, Andante Cantabile (in private, in 1892).

We shall consider the implications of this information after exploring the final group of pieces.

Of great interest are those works composed for Koussevitzky to play, but that he never performed. Not only is the Koussevitzky connection interesting, but they include music of a stature at least equal to that of other often-performed bass repertoire, and from a period during which little solo repertoire was composed. These are listed in chronological order.

• Georgi Konius, Concerto (1910). The dedication to Koussevitzky is recorded in Musical Courier.59 Georgi Konius (1862-1933) was professor at the Moscow Conservatory and one of the outstanding Russian composers of his generation, whose students included Scriabin and Glière. His name is also transliterated as Conus: he was the brother of Julius Conus, the violinist whose Concerto (1898) was championed first by Kreisler, including performances conducted by Koussevitzky, and later by Heifetz. The relationship between Konius's bass concerto and the one attributed to Koussevitzky is intriguing, due to the formal similarities. Both are in F-sharp minor and begin with an introduction based on a tonic 6/4 chord. The large-scale form comprises three movements, with the second movement played attacca, and with much of the first movement recapitulated in the third movement. Given that the earlier concerto was ghost-written by Konius's student Glière, one wonders if Konius intended his work as an improvement upon, even an implied critique of, the earlier concerto. However, perhaps this structural scheme was used more broadly in Russia at the time.

Although Konius and Koussevitzky moved in the same musical circles and had extensive contact, it seems more than a coincidence that Konius wrote the concerto rather directly after Koussevitzky conducted Konius's Scenes Enfantines for Orchestra, op. 1, with the Berlin Philharmonic on Mar. 6, 1908.60 What is certain is that Koussevitzky, who by 1910 was concentrating on his conducting career, never performed the Konius Concerto. It was only published, by Muzyka, in 1969.

• Arthur Lourié, Sonata for Violin and Bass (1924). Lourié is well-known as the author of the previously cited authorized biography of Koussevitzky, completed in 1929 and published in 1931. Did he compose this Sonata for Koussevitzky? The recent Funeral Games in Honor of Arthur Vincent Lourié fills in considerable detail, including items both juicy and embarrassing, but not enough for certainty on this particular question. Lourié and Koussevitzky had known each other since 1915. Lourié's year of 1924, during which he composed this sonata, began in Paris, continued in Wiesbaden, and ended in Paris again, where he worked at Koussevitzky's édition Russe de musique, including preparing piano reductions of Stravinsky. The Koussevitzky-Lourié correspondence, in the Library of Congress, includes an unfortunate gap from late 1924 to the middle of 1929, so the question of the origins of this piece remains open.61 If however this substantial and remarkable work was intended for Koussevitzky, Lourié made a major blunder in composing it for a double bass in the usual orchestral tuning rather than the solo tuning Koussevitzky invariably used as soloist. This tuning apparently proved no barrier to a performance in a concert of the International Composers' Guild, Aeolian Hall, Dec. 27, 1925, an event that presumably accounts for the copy in the New York Public Library, (Figure 15).62

Figure 15: Lourié, Sonata, opening (New York Public Library)

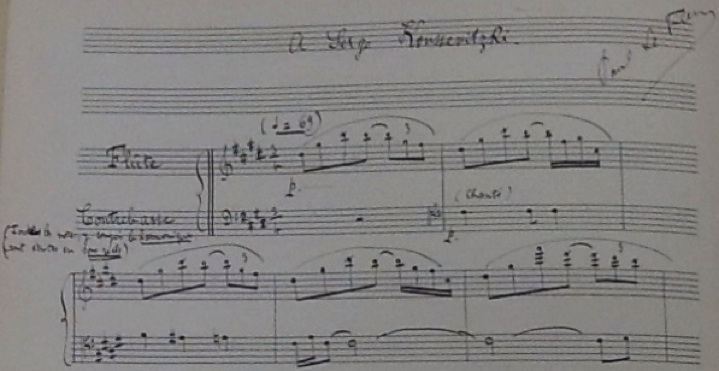

• Paul le Flem, "A Serge Koussevitzki" for flute and bass. On Sept. 2, 1924, Koussevitzky was given the remarkable honor of becoming a Chevalier de la Légion d'Honneur. The next day he sailed off to take up his new post as Music Director of the Boston Symphony. He next returned to Paris the following summer to conduct a series of concerts, as he continued to do each summer through 1929. It was not until June 18, 1925, therefore, that his French friends — performers, composers, critics — were able to fête him with an evening's entertainment, held in the party room of the daily arts journal, Comœdia. This piece, along with Roussel Duo listed below, was composed for that event.63 The manuscripts of both duos are now housed in the Library of Congress. The opening of the work by Paul le Flem is in Figure 16.

Figure 16: Le Flem, "A Serge Koussevitzki," opening (Library of Congress)

Le Flem eventually transcribed the piece as "Pièce pour flute et violoncelle." The manuscript of this later version is held by the Médiathèque Musicale Mahler in Paris and excerpted in Phillippe Gonin's Vie et Œuvre de Paul Le Flem.64 A manuscript copy of the flute and cello version, prepared and provided by Michel Lemeu, has been helpful in preparing an edition of the original version.

The other works presented on that occasion, not inclusive of the double bass, include several noteworthy composers, two of whose manuscript contributions are also in the Library of Congress: Paul Dukas's Allegro for piano, "Corillon-Fanfare," was performed by Alfred Cortot, and Alexis Roland-Manuel presented a Maestoso for harp quartet, a soggetto cavetto of "Serge" and "Natacha" (reduced to a solo harp performance that evening by Carlos Salzedo). Also in the Library of Congress is the manuscript of another piece that stems from that occasion: a brief, anonymous, and undated "Saluons le chef eminent" for solo voice, 2-part chorus, and piano.

Among other items from that event, whose manuscripts are not housed in the Library of Congress, Sergei Prokofiev offered a piece for pianola; Arthur Honegger supplied the "Hommage du trombone exprimant la tristesse de l'auteur absent" for trombone and piano; and Alexandre Tansman performed his Five Impromptus for solo piano.65

Interesting parallels link le Flem and Roland-Manuel. First, both studied with Roussel, which might have contributed to how they got tapped for this specific occasion. Moreover, both became more active as a critic than as a composer later in life, a trait they shared with Dukas.

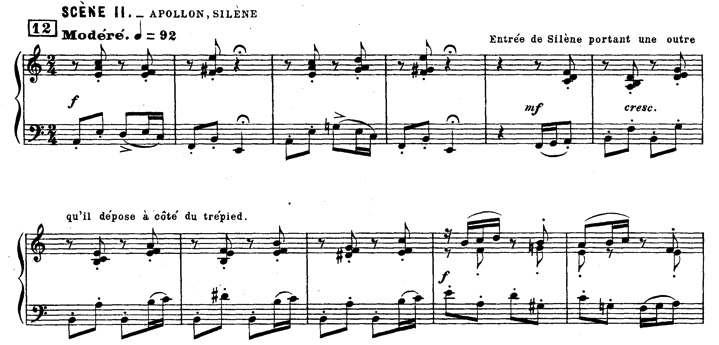

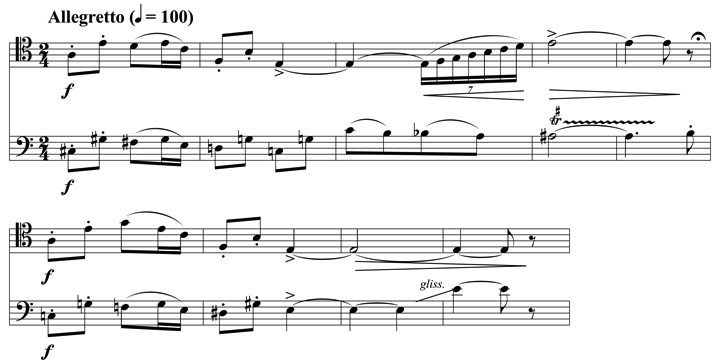

• Albert Roussel, Duo (with bassoon). Some details on the occasion of composition are given above, under le Flem. The full title on the manuscript in the Library of Congress is "Duo pour basson et contrebasse sur un theme de La naissance de la lyre." That is, the principal thematic material of the Duo is drawn from Roussel's one-act "Conte lyrique d'apres Sophocle," La Naissance de la Lyre, op. 24. Although this opera was completed on Sept. 14, 1923 and dedicated to Koussevitzky, it was not premiered until July 1, 1925 under the baton of Philippe Gaubert. The theme in question, which is always associated with Silenus, is first presented in Scene II, and in A minor. (Figure 17)

Figure 17: Roussel, La Naissance de la Lyre: "Silenus" Theme

In the presentation copy in the Library of Congress it is presented by the bass in this way (Figure 18):

Figure 18: Roussel Duo: "Silenus" Theme, mm. 118-27

The same theme is also transposed into major mode near the end of the piece (Figure 19).66

Figure 19: Roussel Duo, "Silenus" Theme, final presentation (major mode), mm. 148-51

Note that the presentation copy calls for orchestrally tuned bass. In the published edition (Durand, 1943) the piece is transposed up a step: this transposition mirrors what Koussevitzky did with a number of cello pieces, enabling him to use solo tuning, finger the piece in the original key, and leave it to the accompanying instrument to accommodate the change, as seen by comparing Figure 20 and Figure 21. The published score also uses the very unusual — almost unique — strategy of notating the scordatura in sounding pitch rather than the usual transposition down a second (plus, in both cases, the usual octave transposition).

Figure 20: Koussevitzky's copy of Roussel Duo, opening (Library of Congress)

Figure 21: Roussel Duo, opening (Durand, 1947)

Since the original version of the bassoon part covers the range Bb2-C5, the published edition requires C3-D5, which, though not as extreme as the high E in the solo from Ravel's Piano Concerto in G Major (1929-31), does range as high as the opening solo from Le Sacre. For the fête in Paris in 1925, the piece was interpreted on harp by Carlos Salzedo.67 The Duo was formally premiered posthumously by bassoonist Fernand Oubradous and cellist Andre Navarra in 1937.68 Although the recent edition by Karsten Lauke, published by Saier & Hug (Berlin, 2008) and republished by Walhall (Magdeburg, 2016), includes material for both orchestrally-tuned and solo-tuned bass, the text is derived from the Durand edition, not the Library of Congress copy.

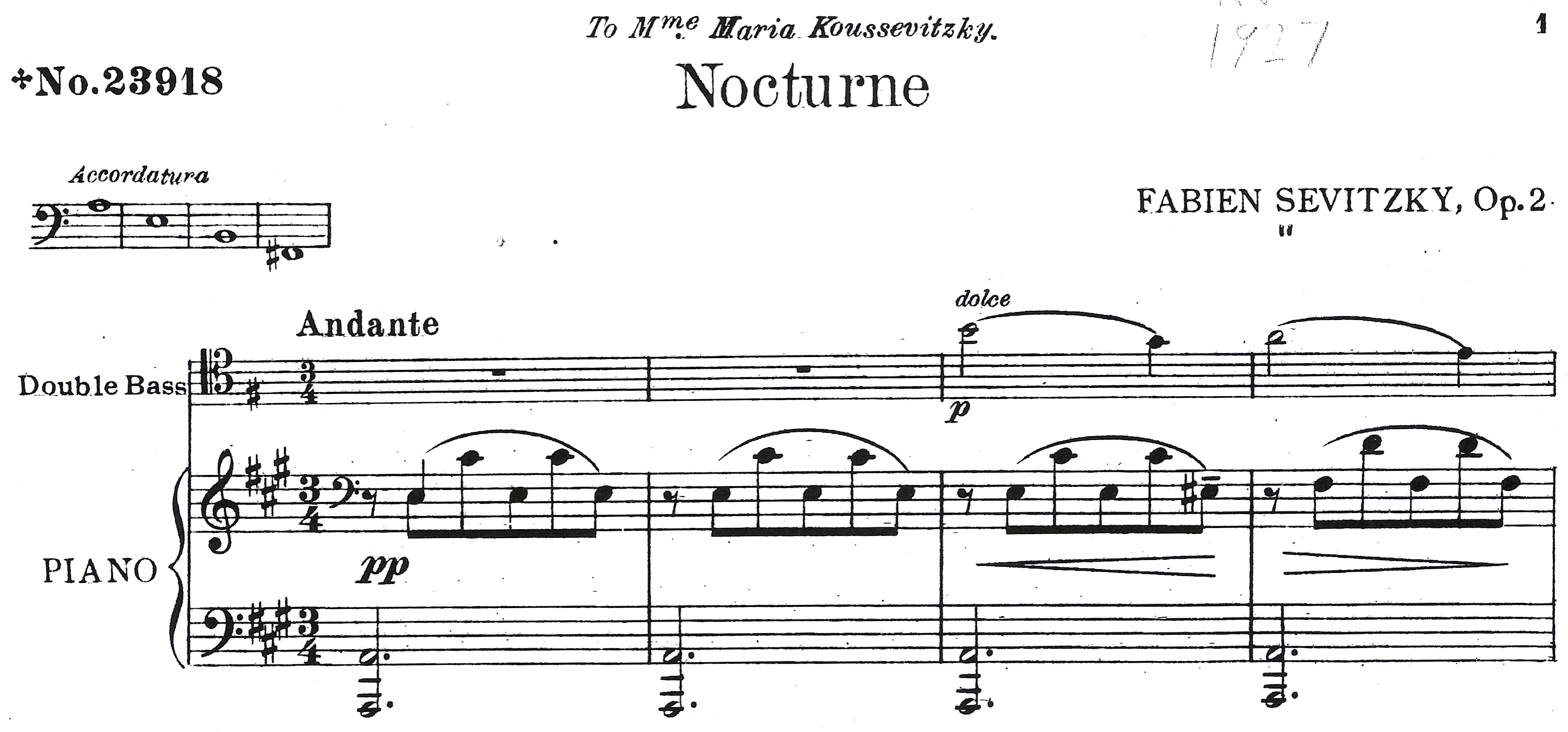

• Fabian Sevitzky, Four pieces (pub. 1927)

Nocturne

Beethoven, Menuet

Sevitzky, Chanson Triste

Dvořák, Humoreske

Sevitzky (1893-1967) was not only Koussevitzky's nephew, he was also, like his uncle, a successful bassist who later turned conductor. Some confusion and competition was inevitable, leading to Sevitzky's truncation of his last name. When Koussevitzky performed his first Boston recital, Sevitzky was a member of the Philadelphia Orchestra. That year Sevitzky published four pieces with Theodore Presser. These comprised two original compositions — a Chanson Triste, op. 1, and a Nocturne (marked "Andante"), op. 2 — and two transcriptions: a Beethoven Menuet and the Dvořák "Humoreske."69 The parallels with Koussevitzky's four salon pieces seem more than coincidental:

|

Serge Koussevitzky Andante, op. 1, no. 1 Valse Miniature, op. 1, no. 2 Chanson Triste, op. 2 Humoreske, op. 4 |

Fabian Sevitzky Sevitzky, Nocturne, op. 2 (marked Andante) Beethoven, Menuet (a dance in triple meter) Sevitzky, Chanson Triste, op. 1 Dvořák, Humoreske |

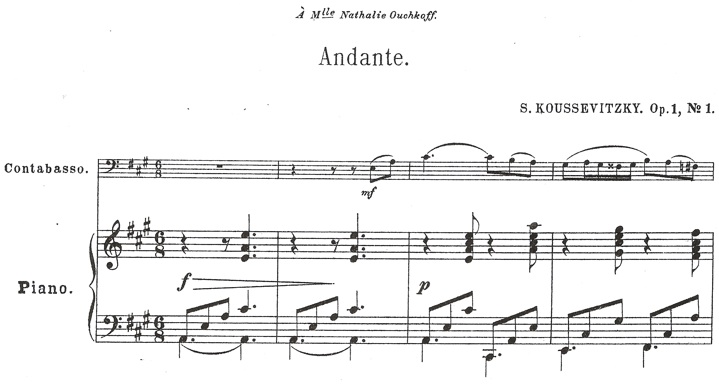

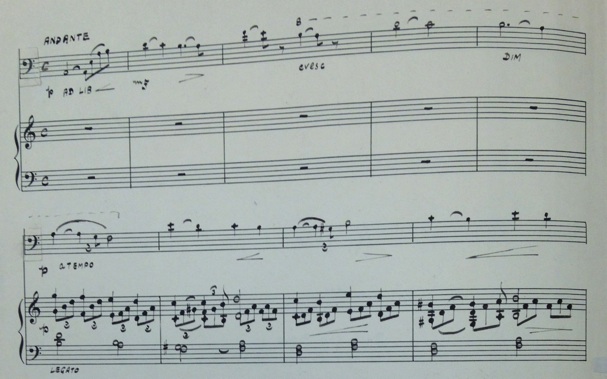

Note, too, the similarities between the openings of the two Andantes (Figure 22 and Figure 23): both in A major, in triple meter, with similar introductions, and dedicated to their wives (each of whom are given French titles).

Figure 22: Koussevitzky, "Andante," opening

Figure 23: Sevitzky, "Nocturne," opening

Was Sevitzky drafting behind his uncle? Comparing? Competing? We can only speculate, but some reference to his elder relation is apparent.

• Eugènie de Zanco, "Inspiration" for bass and piano. The unpublished manuscript in the Library of Congress bears the title page, "Inspiration/by Eugenie de Zanco/Conceived during the 'Koussevitzky Concert'/in Chicago, on Nov. 3d 1927." Since Koussevitzky conducted the BSO in Chicago on that evening of the 3rd, this could either mean that de Zanco composed the piece that very evening or, more likely, shortly afterward.

Some biographical details about de Zanco can be gathered from scattered press mentions. According to Musical America, pianist Eugènie de Primo, reportedly a grandniece of Leo Tolstoy, was the wife of dramatic tenor Sergio [Servais] de Zanco.70 She was also known as the Comtesse Wandayne de Tolstoy.71 She lived in Petrograd, where she was pianist to the Russian Imperial court, and later in Paris, where she appeared as soloist with the Colonne orchestra.72 Her photo appears in an advertisement in The Music News, Dec. 8, 1922, p. 23.73 "Inspiration" comprises just 17 measures of pleasant but amateurish music, including double-stops that require an E-flat string and with rhythms that are not well-aligned between staves.

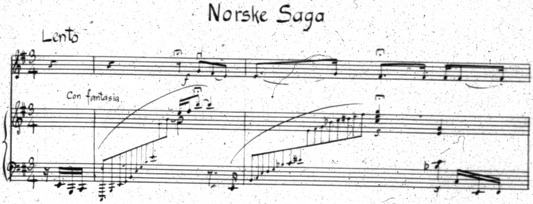

• Charles Martin Loeffler, Norske Saga. Full title: "Norske Saga/Divertissement/pour/Contrebasse et Piano/(D'après deux motifs norvégians et d'un Ranz da vaches, tirés da la Collection Nationale De Musique Norvégienne/publiée par Warmuth à Christiania.)/compose/pour/Ch. M. Loeffler" [Divertimento for Double-Bass and Piano after two Norwegian motives and one "ranz de vaches" taken from the Collection, "Norwegian National Music," published by Warmuth in Christiana].

The piece went through more than one version. First composed as "Norske Land" for viola d'amore and piano, Loeffler first revised it as "Eery Moonlight" for violin and piano, and then in two versions including the double bass, both titled "Norske Saga": the version for viola d'amore, double bass, and piano, which is housed at Yale, is less developed, while the version for double bass and piano, with a final version in BPL, the opening of which is shown in Figure 24, is completed. In a note to Koussevitzky dated March 16, 1929, Loeffler gushed, "There remains in my ear still the memory of the sonorities all together unexpected as well as beautiful that you have known how to create and draw from your beautiful instrument," and referred to "the mysterious and tonal alchemy of which you are the unique musician."74

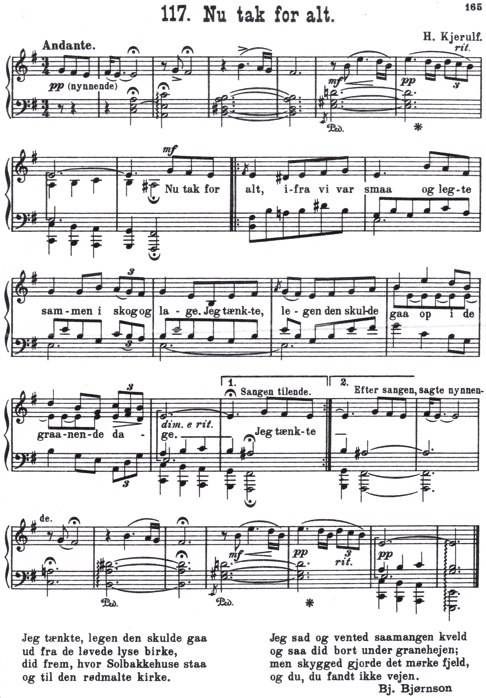

Loeffler's description of his source material is concise, even terse, but can be expanded, albeit speculatively. Warmuth's Norwegian National Music comprises eight volumes, published around 1880. It is quite likely, however, that Loeffler did not consult these volumes directly, but instead took advantage of two other related volumes. The introduction and first theme comes from the first of those two volumes, Norges Melodier, Vol. 2, from which he borrowed song 117, "Nu tak for alt" (Figure 25).75

Figure 24: Koussevitzky's copy of Loeffler, "Norske Saga," opening (BPL)

Figure 25: Norges Melodier, Vol. 2, song 117, "Nu tak for alt"

The probable second source was a selected anthology drawn from Norwegian National Music and published locally in Boston by the Oliver Ditson Company, The Norway Music Album (1881).76 The borrowed melody from this source proves to be a Halling dance rather than a ranz de vaches; the change is perhaps reflective of Loeffler's well-known antipathy for all things Teutonic and preference for all things Gallic. This specific dance, taken from a collection by Ole Bull, is also included in the Oliver Ditson volume. The Halling dance is well worth describing.

The scene of action of this rustic dance is apt to be a country barn, and it is danced by the young men alone, usually one at a time. Its most startling feature is the kicking of the beam in the ceiling by the dancer. He who can skillfully and gracefully accomplish this feat to the satisfaction of the girl spectators, is hailed as the hero of the occasion, and can have pretty much his choice of partners for the other dances; but he who fails to touch the beam when the fiddler's bow makes the string vibrate with the strong marcato, or who performs the feat awkwardly, becomes the universal object of ridicule, and might just as well go home, for the girl dancers will all be shy of him.77

Figure 26 shows Ole Bull's version as reprinted by Oliver Ditson:

Figure 26: Bull, "Halling Dance," pub. Oliver Ditson

This, Loeffler minimally recasts beginning in m. 44 (transposed down a whole step to accommodate the bass's usual scordatura) (Figure 27):

Figure 27: Loeffler, Halling-Dance from "Norske Saga"

• Yves Chardon, Basso Concerto: À Monsieur Serge Koussevitzky (1929). Cellist and composer Yves Chardon (1902-2000) was brought from Paris by Koussevitzky in 1928 to join the Boston Symphony.78 In 1943 he moved to the Minneapolis Symphony, where he played principal for Dimitri Mitropoulos and served as assistant conductor for seven seasons. When Mitropoulos assumed the music directorship of the New York Philharmonic in 1950, Chardon moved to Florida, where he founded the Orlando Symphony (now the Central Florida Symphony). In 1952 he moved to New York, where he served as alternate principal in the Met until 1976. He then retired to New Hampshire.

The instrumentation of this concerto, housed in BPL (Figure 28), shows an obvious debt to Stravinsky's Octet, also in three movements, premiered in Paris in 1923, conducted by Stravinsky in a concert organized by Koussevitzky. The style, however, is rooted in the pandiatonicism of Les Six.

Figure 28: Chardon, First page of score from Basso Concerto (BPL)

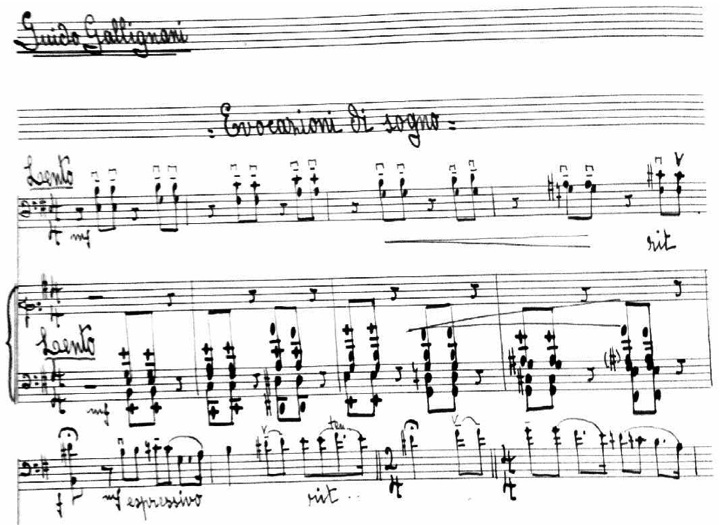

• Guido Gallignani, "Evocazioni di sogno" for bass and piano, op. 15. Gallignani (1880-1974), one of the great double bassists of his generation, a native of Lugo di Romagna, made his living abroad: first in Malmö, Sweden, then in San Salvador and Guatemala, finally teaching at the University of Mexico City for 34 years. He retired to Italy for his final years. Gallignani presented this piece (Figure 29) to Koussevitzky in 1934; Koussevitzky had previously accepted Gallignani's invitations to attend his New York City recitals, performed on Nov. 14, 1931 (which included Koussevitzky's concerto), and March 4, 1932. The manuscript is listed in the catalog of BPL. "Evocazioni" also exists in a version for bass and orchestra.79

Figure 29: Gallignani, "Evocazioni di sogno," opening (courtesy of Maria Louisa Miliani)

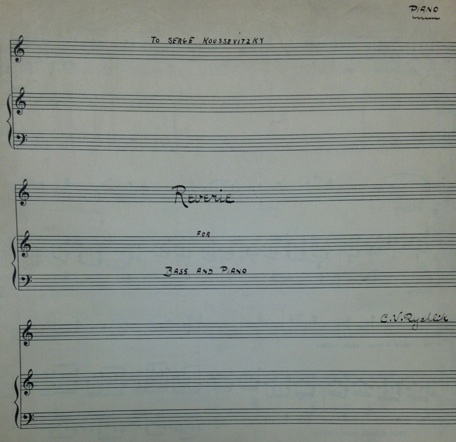

• C.V. Rychlik, "Reverie" for bass and piano. The manuscript is in the Library of Congress and bears the dedication, "To Serge Koussevitzky." Although the score has no date, the Library of Congress catalog lists this as being from 1940: well after Koussevitzky had ended his career as a performing bassist.

Violinist and composer Charles Vaclav Rychlik (1875-1962), born in Cleveland of Czech ancestry, studied in Prague, where he also served as English language coach for Dvořák in preparation for Dvořák's move to the U.S. in 1892. After returning to the U.S. and playing in the Theodore Thomas Orchestra, Rychlik returned to Cleveland and played both in the forerunner of the Cleveland Orchestra and in the Cleveland Orchestra itself, 1901-20, as well as in the Philharmonic String Quartet, 1908-28. He made major contributions to violin pedagogy both as teacher and author. If the year is exact, the piece might have been composed consequent to Koussevitzky conducting the BSO at the Music Hall in Cleveland on Dec. 13, 1940.80 The manuscript is in the Library of Congress (Figure 30 and Figure 31).

Figure 30: Rychlik, cover of "Reverie" (Library of Congress)

Figure 31: Rychlik, "Reverie," opening (Library of Congress)

• Randall Thompson, Trio for Three String Basses. Thompson's most famous composition, the "Alleluia" (1940), was commissioned by Koussevitzky for Tanglewood. Thompson was tapped again for the Trio, composed in honor of Koussevitzky and premiered at the Harvard Club (of which Koussevitzky was a member) in 1949.81 The humor of this neo-Rococo work in four movements can only be fully appreciated in light of Thompson's description of the premiere: "It was solemnly programmed as 'Divertimento for Strings', to be performed by 'Members of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Malcolm H. Holmes, '28, Guest Conductor'."82 The distinguished audience must have been quite surprised to see Holmes confronting three bassists. The work is in the general style of a classical period divertimento in four movements.

Of course this study provides biographical detail from the life of that fascinating figure, Koussevitzky. But it is also a study of repertoire. One primary task of musicology is the positivist goal of making music available. At that level, this project is its own justification. However, other points can also be drawn from the information presented here. For example, this survey gives an interesting window into the resources available to a bassist of a century ago. Even major original works for bass such as Mozart's "Per Questa Bella Mano" might only be available for performance in a manuscript edition. Indeed, much of Koussevitzky's repertoire was in manuscript. This highlights by contrast the significance of Simandl's publication series, both the Hohe Schule and the other works published under his aegis. Indeed, apart from Simandl's efforts, Gliére's op. 8, and his own salon pieces, the only published material composed for bass that Koussevitzky used was by Bottesini, and even there, he used a manuscript copy of the Tarantella. One imagines Koussevitzky — or indeed, any bassist of his time with ambitions as a soloist — seizing upon any publication whatsoever of music for the solo double bass. Of those works, we see Koussevitzky's general gravitation toward works by famous composers — not an uncommon preference.

Most intriguing is the slenderness of Koussevitzky's repertoire. He repeatedly played six pieces — by Bruch, Casadesus, Handel, himself/Glière, Mozart, Stein — with orchestra (with piano when necessary); on one occasion he played the Saint-Saëns Cello Concerto no. 1 with orchestra and on another, a Bottesini double concerto with piano. He played three chamber works: by Casadesus, Mozart, and Schubert. Of those three, he only performed the Mozart and the Schubert one time, and at the end of his career. He played three baroque sonatas and one baroque slow movement. He played about a dozen other small pieces, some of which are unconfirmed: by Bach, Beethoven, Bottesini, Glière, himself, Láska, Scriabin, and Tchaikovsky. By current standards, this is not much for a major career, even a brief and intermittent one. Admittedly, this list is cautious. We know that we have lost performance material for music that we know he performed, such as the Stein Concertstück. It is quite possible that the performance material for some of his other repertoire has gone the same way. One imagines him pressing the lost transcription of the Strauss Sonata into the hands of a younger colleague — "Here, you must try this" — and never receiving it back.83 Indeed, it is possible that some of Koussevitzky's personal performance library still lies in other private hands, awaiting rediscovery.

This aspect of Koussevitzky's career can be clarified by the negative space surrounding it. He played little of the previous repertoire available at the time. For example, of the core repertory of 51 items in Simandl's Hohe Schule, we can be certain Koussevitzky played a couple of them: Lvovsky, Handel. He was the dedicatee of substantial works by composers he championed in his programming as a conductor — Glière, Konius, Loeffler — yet he never performed them. He had a transcription prepared by another of his favorites, Scriabin, but there is no evidence he performed it.

This is a polar opposite to his choices as a conductor. On the podium he was known as a champion of new music, with a voracious appetite for premieres.84 This appetite is clear from his first performance as a conductor, with its premiere of Glière's Second Symphony, and continued through his career.

Koussevitzky's conservatism as a bassist extended beyond the size of his repertoire. He relied heavily on repertoire that would raise no eyebrows among audience members. Where was the questing spirit that would perform a work composed by an unknown 24-year-old Aaron Copland? He also seemingly accepted quick answers to questions of transposition, such as changing a clef or minimally transposing a piece by a step. This bifurcation of personality, with the bassist playing it safe and conservative, while the conductor constantly expanded the envelope of the orchestral repertoire, is most remarkable.

Even from this scant repertoire, certain items from Koussevitzky's repertoire are due for a revival. In the case of the Casadesus Sinfonia Concertante, this has already begun. In the case of other works, perhaps a new dawn is approaching. In this day of mash-ups, audiences are, hopefully, more accepting of such pieces that combine elements of different eras, especially if full disclosure is provided. Similarly, the exploration of Koussevitzky's repertoire makes possible a larger place for programs featuring forgotten or even somewhat speculative items. We have become more tolerant of a performance of an edition of Tchaikovsky's "Andante Cantabile" that just might be the one that Koussevitzky played with Tchaikovsky himself than we might have been fifty years ago.

Finally, others of these pieces can now make their initial forays onto the concert stage. Indeed, some of Koussevitzky's repertoire, including both works that he performed and works that he did not, have been revived the past few years. In addition to others' performances of the Casadesus Sinfonia Concertante, the author has performed the works by Chardon, Galliard, Gallignani, Konius, le Flem, Loeffler, Roussel (original version), Rychlik, and Stein. The double bass repertoire is poor in fine original works. The interesting historical circumstances that gave rise to these pieces can only add to their luster.

Origins can be even more important when contemplating transcriptions. This can be illustrated in reverse. A solo bass CD recently added to my library, while brilliantly played, suffers from the inclusion of a transcription with liner notes that can be paraphrased as, "I pulled this piece out of my University library's stacks almost at random. It sounded good to me, so I figured that if the composer knew what I had done, he would have approved." Another, better approach is available: perform transcriptions of historical significance, and let the audience know the circumstances that gave rise to this version. If they hate the playing, at least they can think about Koussevitzky. The author has performed the transcription of Bach, Handel (the Largo) and Scriabin in this light. One might think of this as moving the art of transcription from a hunter-gatherer culture, consuming whatever comes to hand and relentlessly searching for something new, to one of conservationists, seeking out what is in danger of being lost or undervalued, bringing it to public attention, and preserving it for the future.

Index to Koussevitzky items from Musical Courier

Abbreviations: NK for Natalie Koussevitzky (and variant spellings); SK for Serge Koussevitzky (and variant spellings). BPO for Berlin Philharmonic; BSO for Boston Symphony Orchestra; LSO for London Symphony Orchestra. Musical Courier used "Leipsic" for "Leipzig."

Vol. 46, no. 16 (April 22, 1903): 5-6. Review of 1903 Berlin recital.

Vol. 46, no. 21 (May 27, 1903): 9. Another review of 1903 Berlin recital.

Vol. 47, no. 14 (Sept. 30, 1903): 12-13. Announcing concert season in Dresden, inc. SK.

Vol. 47, no. 23 (Nov. 29, 1903): SK to play in Berlin, Nov. 29.

Vol. 47, no. 26 (Dec. 23, 1903): 16-17. Review of SK's 2nd Berlin recital.

Ibid.: 16-17. Review of Berlin recital. Date unclear. Nov. 29 was previously announced; list of concerts later on same page cites date of Dec. 7.

Vol. 51, no. 22 (Nov. 29, 1905): 6. SK recital postponed "owing to the great revulsion in Russia."

Vol. 53, no. 20 (Nov. 14, 1906): 8. Announcing SK recital on Nov. 20. Ascribes cancellation of 1905 to NK's illness.

Vol. 53, no. 23 (Dec. 5, 1906): 40. SK recital "during the coming weeks."

Vol. 53, no. 24 (Dec. 12, 1906): 14-15. Review of Berlin recital.

Ibid.: 30. Review of Leipzig recital.

Vol. 53, no. 25 (Dec. 19, 1906): 26E. Report on conversation on Russian music; SK present.

Vol. 54, no. 1 (Jan. 2, 1907): 5. SK included in discussion of musicians' income.

Vol. 54, no. 4 (Jan. 23, 1907): 5. Photo of SK, who talks of American tour.

Vol. 54, no. 5 (Jan. 30, 1907): 5. Photo of SK with caption.

Vol. 54, no. 8 (Feb. 20, 1907): 8. SK's tour itinerary.

Ibid.: 22. SK the one great new star of 1906.

Vol. 54, no. 9 (Feb. 27, 1907): 7. SK great success in first Vienna recital.

Ibid.: 24. SK in photo from party in Berlin.

Ibid.: 29. Full page about SK with Russian press notices.

Vol. 54, no. 9 (Feb. 27, 1907): 48. Review of second Leipsic recital.

Vol. 54, no. 10 (March 6, 1907): 9. SK bought Maggini in Hungary.

Vol. 54, no. 11 (March 13, 1907): 5. SK sponsored Glière concert.

Ibid.: 17. Review of second Vienna recital, Feb. 1.

Vol. 54, no. 13 (March 27, 1907): 7. SK attended Tina Lerner recital.

Vol. 54, no. 14 (April 3, 1907). SK on cover.

Ibid.: 32. Review, with extracts from local papers, of second Berlin recital, March 27.

Vol. 54, no. 16 (April 17, 1907): 7. Press notices from Berlin, Prague.

Ibid.: 11. Review of Vienna recital; also included in list of concerts, p. 12.

Vol. 54, no. 19 (May 8, 1907): 21-22. Review of pair of recitals, with Paris press notices.

Vol. 54, no. 20 (May 15, 1907): 7. Press notices from Berlin, Hamburg.

Ibid.: 9. SK played at reception in Paris.

Vol. 54, no. 21 (May 22, 1907): 6. Press notices from Berlin.

Ibid.: 17. Fabian Sevitzky, SK's nephew, in Philadelphia.

Vol. 54, no. 22 (May 29, 1907): 9. Leipzig review, Nov. 17, 1906.

Vol. 54, no. 23 (June 5, 1907): 8. SK performed with "Society of Concerts for Ancient Instruments."

Ibid.: 10. Press cutting, Berlin, from April 3, 1907.

Vol. 54, no. 24 (June 12, 1907): 9. SK present at an event.

Ibid.: 11. Press notices from Berlin (1903), Leipsic (1906).

Ibid.: 14. SK plays in private reception in Paris.

Ibid.: 15. Review of London recital (presumably of May 22, 1907).

Vol. 54, no. 25 (June 19, 1907): 8. Press cuttings from Berlin.

Vol. 54, no. 26 (June 26, 1907): 30. Press notices from Berlin.

Vol. 55, no. 1 (July 3, 1907): 6. Recital review from Leipsic, Nov. 17, 1906.

Ibid.: 9. Review of second London recital.

Vol. 55, no. 10 (Sept. 4, 1907): 25. Press notices from Budapest.

Vol. 55, no. 11 (Sept. 11, 1907): 10. SK summering in Biarritz. Ordered new bass.

Vol. 55, no. 12 (Sept. 18, 1907): 25. Press notices from Leipsic, Feb. 6-8, 1907.

Vol. 55, no. 14 (Oct. 2, 1907): 17. More press notices from Leipsic.

Vol. 55. no. 15 (Oct. 9, 1907): 10. Press notices from Munich, Augsburg, from Feb. 1907.

Vol. 55, no. 17 (Oct. 23, 1907): 15. Press notices from Vienna, Feb. 1907.

Vol. 55, no. 18 (Oct. 30, 1907): 10. Announcement of SK's upcoming recital, Berlin, Oct. 29.

Vol. 55, no. 19 (Nov. 6, 1907): 9. Photo of party at Kussewitzky's house.

Ibid, 10: photo of "Mr. and Mme. Kussewitzky at Biarritz."

Vol. 55, no. 20 (Nov. 13, 1907): 6. Announcement of SK's upcoming Berlin recital.

Ibid.: 30. Press notices from London, May 23-June 1, 1907.

Vol. 55, no. 21 (Nov. 20, 1907): 9. Review of SK recital, Berlin, and of private performance of Society of Ancient Instruments given in SK's home.

Vol. 55, no. 22 (Dec. 4, 1907), cover. Photo of SK.

Ibid, 19. Press notices, London, May-July, 1907.

Vol. 55, no. 24 (Dec. 18, 1907): 31. Press notices, London, May-June 1907.

Vol. 56, no. 2 (Jan. 8, 1908): 11. Press notices, London and Sheffield, May, 1907.

Vol. 56, no. 6 (Feb. 5, 1908): 17. Review of program, Berlin, Jan. 23, 1908 and preview of program, Berlin, March 6, 1908.

Ibid, 30: Leipsic column. SK solo premiere with Gewandhaus next week.

Vol. 56, no. 7 (Feb. 12, 1908): 11. Review of SK's conducting debut, BPO.

Ibid, 26. Review of SK's solo debut with Gewandhaus.

Vol. 56, no. 8 (Feb. 17, 1908): 10. Review of SK solo debut with Gewandhaus.

Vol. 56, no. 10 (Mar. 4, 1908): 13-14. Preview of SK's 2nd concert as conductor.

Vol. 56, no. 11 (Mar. 11, 1908): 12. Review of SK with Colonne Orchestra.

Vol. 56, no. 13 (Mar. 25, 1908): 5. Review of SK's second conducting concert in Berlin.

Vol. 56, no. 18 (April 29, 1908): 10. Ad for U.S. tour, 1908-1909 season. Also includes Ephraim Zimbalist, Tina Lerner. Repeated weekly (except Sept. 30) through Nov. 18. After that, only Zimbalist and Lerner listed.

Vol. 56, no. 19 (May 6, 1908): 6. SK recuperating in Riviera. Conducting and soloist appearances in London in May.

Vol. 56, no. 21 (May 20, 1908): 5-6. Announcement of SK's upcoming U.S. tour.

Vol. 56, no. 23 (June 3, 1908): 9. SK as conductor and recitalist in London.

Vol. 56, no. 25 (June 17, 1908): 16. Review of second conducting concert with LSO.

Vol. 57, no. 1 (July 1, 1908): 9. Bio, reviews of second LSO conducting concert.

Ibid, 9. Review of concert conducting Vienna Konzertverein.

Vol. 57, no. 16 (Oct. 14, 1908): 7. Recalls SK playing Mozart bassoon concerto.

Vol. 58, no. 5 (Feb. 3, 1909): 6. SK back in Berlin. Upcoming performance plans.

Vol. 58, no. 11 (March 17, 1909), 5. Review of Berlin recital.

Ibid, 14-15. SK gave Dresden recital: review to follow.

Vol. 58, no. 14 (April 7, 1909): 12. Dresden recital review.

Ibid, 48. Review, SK recital, Stockholm; announcement of second upcoming recital.

Vol. 58, no. 15 (April 14, 1909): 6. SK founding publishing house.

Ibid, 23: "Stockholm Music." Review of second recital.

Vol. 58, no. 20 (May 19, 1909): 5. London recital postponed due to broken instrument.

Ibid, 7: SK attended jubilee honoring Landeker.

Vol. 58, no. 21 (May 26, 1909): 7. SK as conductor and recitalist in London.