Volume 9, September 2017

|

|

Serge Koussevitzky Andante, op. 1, no. 1 Valse Miniature, op. 1, no. 2 Chanson Triste, op. 2 Humoreske, op. 4 |

Fabian Sevitzky Sevitzky, Nocturne, op. 2 (marked Andante) Beethoven, Menuet (a dance in triple meter) Sevitzky, Chanson Triste, op. 1 Dvořák, Humoreske |

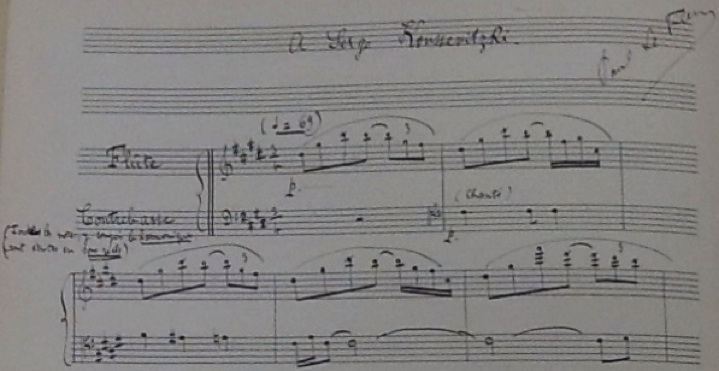

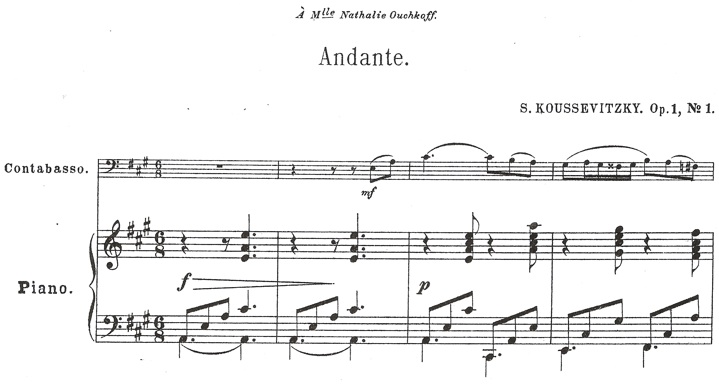

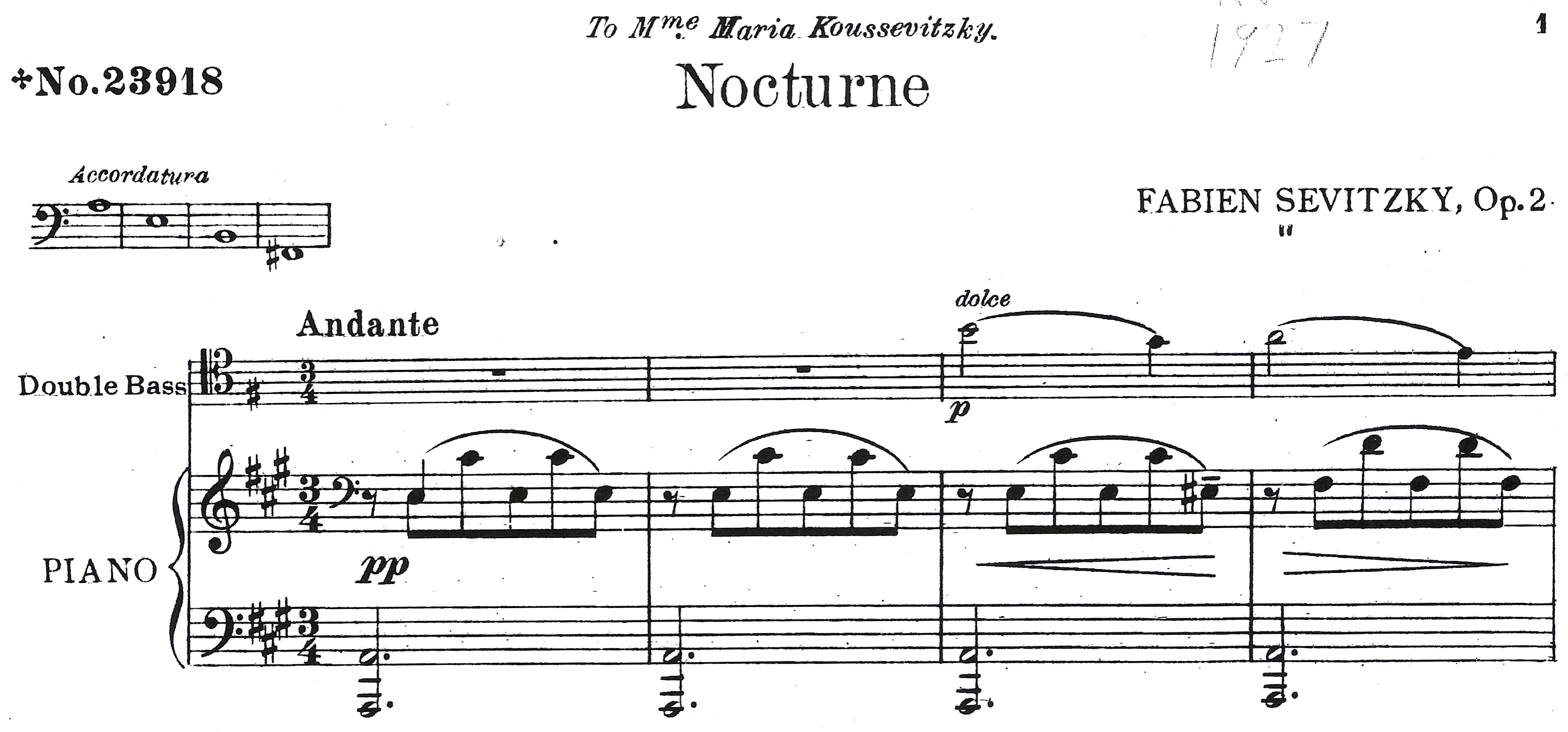

Note, too, the similarities between the openings of the two Andantes (Figure 22 and Figure 23): both in A major, in triple meter, with similar introductions, and dedicated to their wives (each of whom are given French titles).

Figure 22: Koussevitzky, "Andante," opening

Figure 23: Sevitzky, "Nocturne," opening

Was Sevitzky drafting behind his uncle? Comparing? Competing? We can only speculate, but some reference to his elder relation is apparent.

• Eugènie de Zanco, "Inspiration" for bass and piano. The unpublished manuscript in the Library of Congress bears the title page, "Inspiration/by Eugenie de Zanco/Conceived during the 'Koussevitzky Concert'/in Chicago, on Nov. 3d 1927." Since Koussevitzky conducted the BSO in Chicago on that evening of the 3rd, this could either mean that de Zanco composed the piece that very evening or, more likely, shortly afterward.

Some biographical details about de Zanco can be gathered from scattered press mentions. According to Musical America, pianist Eugènie de Primo, reportedly a grandniece of Leo Tolstoy, was the wife of dramatic tenor Sergio [Servais] de Zanco.70 She was also known as the Comtesse Wandayne de Tolstoy.71 She lived in Petrograd, where she was pianist to the Russian Imperial court, and later in Paris, where she appeared as soloist with the Colonne orchestra.72 Her photo appears in an advertisement in The Music News, Dec. 8, 1922, p. 23.73 "Inspiration" comprises just 17 measures of pleasant but amateurish music, including double-stops that require an E-flat string and with rhythms that are not well-aligned between staves.

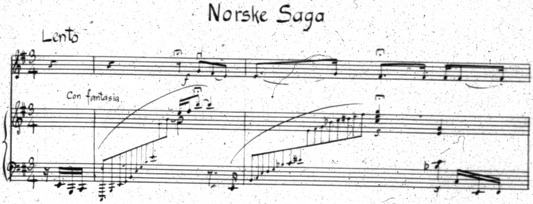

• Charles Martin Loeffler, Norske Saga. Full title: "Norske Saga/Divertissement/pour/Contrebasse et Piano/(D'après deux motifs norvégians et d'un Ranz da vaches, tirés da la Collection Nationale De Musique Norvégienne/publiée par Warmuth à Christiania.)/compose/pour/Ch. M. Loeffler" [Divertimento for Double-Bass and Piano after two Norwegian motives and one "ranz de vaches" taken from the Collection, "Norwegian National Music," published by Warmuth in Christiana].

The piece went through more than one version. First composed as "Norske Land" for viola d'amore and piano, Loeffler first revised it as "Eery Moonlight" for violin and piano, and then in two versions including the double bass, both titled "Norske Saga": the version for viola d'amore, double bass, and piano, which is housed at Yale, is less developed, while the version for double bass and piano, with a final version in BPL, the opening of which is shown in Figure 24, is completed. In a note to Koussevitzky dated March 16, 1929, Loeffler gushed, "There remains in my ear still the memory of the sonorities all together unexpected as well as beautiful that you have known how to create and draw from your beautiful instrument," and referred to "the mysterious and tonal alchemy of which you are the unique musician."74

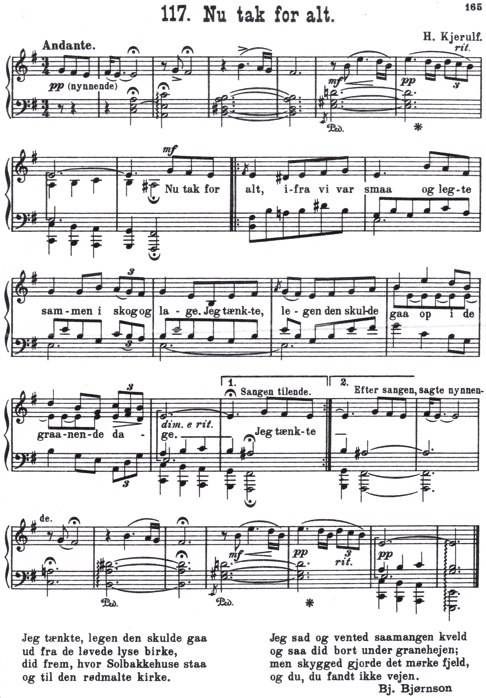

Loeffler's description of his source material is concise, even terse, but can be expanded, albeit speculatively. Warmuth's Norwegian National Music comprises eight volumes, published around 1880. It is quite likely, however, that Loeffler did not consult these volumes directly, but instead took advantage of two other related volumes. The introduction and first theme comes from the first of those two volumes, Norges Melodier, Vol. 2, from which he borrowed song 117, "Nu tak for alt" (Figure 25).75

Figure 24: Koussevitzky's copy of Loeffler, "Norske Saga," opening (BPL)

Figure 25: Norges Melodier, Vol. 2, song 117, "Nu tak for alt"

The probable second source was a selected anthology drawn from Norwegian National Music and published locally in Boston by the Oliver Ditson Company, The Norway Music Album (1881).76 The borrowed melody from this source proves to be a Halling dance rather than a ranz de vaches; the change is perhaps reflective of Loeffler's well-known antipathy for all things Teutonic and preference for all things Gallic. This specific dance, taken from a collection by Ole Bull, is also included in the Oliver Ditson volume. The Halling dance is well worth describing.

The scene of action of this rustic dance is apt to be a country barn, and it is danced by the young men alone, usually one at a time. Its most startling feature is the kicking of the beam in the ceiling by the dancer. He who can skillfully and gracefully accomplish this feat to the satisfaction of the girl spectators, is hailed as the hero of the occasion, and can have pretty much his choice of partners for the other dances; but he who fails to touch the beam when the fiddler's bow makes the string vibrate with the strong marcato, or who performs the feat awkwardly, becomes the universal object of ridicule, and might just as well go home, for the girl dancers will all be shy of him.77

Figure 26 shows Ole Bull's version as reprinted by Oliver Ditson:

Figure 26: Bull, "Halling Dance," pub. Oliver Ditson

This, Loeffler minimally recasts beginning in m. 44 (transposed down a whole step to accommodate the bass's usual scordatura) (Figure 27):

Figure 27: Loeffler, Halling-Dance from "Norske Saga"

• Yves Chardon, Basso Concerto: À Monsieur Serge Koussevitzky (1929). Cellist and composer Yves Chardon (1902-2000) was brought from Paris by Koussevitzky in 1928 to join the Boston Symphony.78 In 1943 he moved to the Minneapolis Symphony, where he played principal for Dimitri Mitropoulos and served as assistant conductor for seven seasons. When Mitropoulos assumed the music directorship of the New York Philharmonic in 1950, Chardon moved to Florida, where he founded the Orlando Symphony (now the Central Florida Symphony). In 1952 he moved to New York, where he served as alternate principal in the Met until 1976. He then retired to New Hampshire.

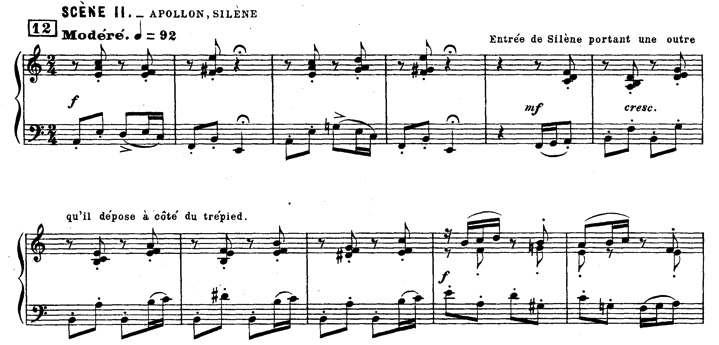

The instrumentation of this concerto, housed in BPL (Figure 28), shows an obvious debt to Stravinsky's Octet, also in three movements, premiered in Paris in 1923, conducted by Stravinsky in a concert organized by Koussevitzky. The style, however, is rooted in the pandiatonicism of Les Six.

Figure 28: Chardon, First page of score from Basso Concerto (BPL)

• Guido Gallignani, "Evocazioni di sogno" for bass and piano, op. 15. Gallignani (1880-1974), one of the great double bassists of his generation, a native of Lugo di Romagna, made his living abroad: first in Malmö, Sweden, then in San Salvador and Guatemala, finally teaching at the University of Mexico City for 34 years. He retired to Italy for his final years. Gallignani presented this piece (Figure 29) to Koussevitzky in 1934; Koussevitzky had previously accepted Gallignani's invitations to attend his New York City recitals, performed on Nov. 14, 1931 (which included Koussevitzky's concerto), and March 4, 1932. The manuscript is listed in the catalog of BPL. "Evocazioni" also exists in a version for bass and orchestra.79

Figure 29: Gallignani, "Evocazioni di sogno," opening (courtesy of Maria Louisa Miliani)

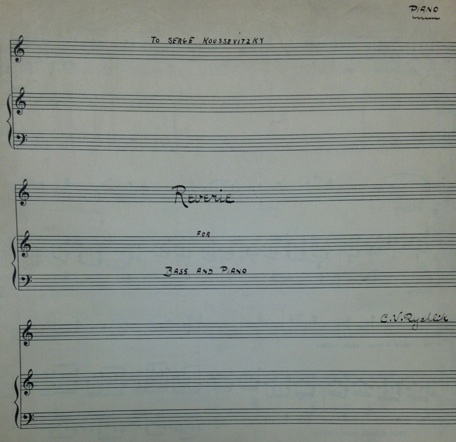

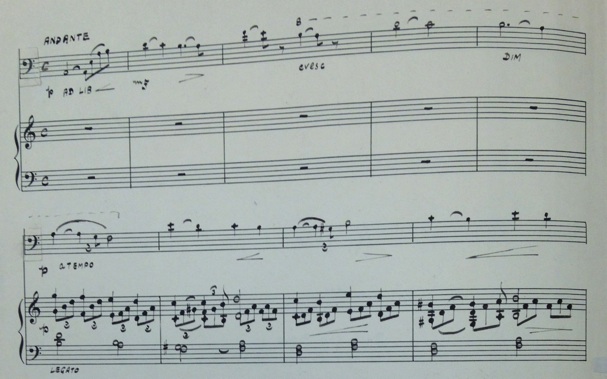

• C.V. Rychlik, "Reverie" for bass and piano. The manuscript is in the Library of Congress and bears the dedication, "To Serge Koussevitzky." Although the score has no date, the Library of Congress catalog lists this as being from 1940: well after Koussevitzky had ended his career as a performing bassist.

Violinist and composer Charles Vaclav Rychlik (1875-1962), born in Cleveland of Czech ancestry, studied in Prague, where he also served as English language coach for Dvořák in preparation for Dvořák's move to the U.S. in 1892. After returning to the U.S. and playing in the Theodore Thomas Orchestra, Rychlik returned to Cleveland and played both in the forerunner of the Cleveland Orchestra and in the Cleveland Orchestra itself, 1901-20, as well as in the Philharmonic String Quartet, 1908-28. He made major contributions to violin pedagogy both as teacher and author. If the year is exact, the piece might have been composed consequent to Koussevitzky conducting the BSO at the Music Hall in Cleveland on Dec. 13, 1940.80 The manuscript is in the Library of Congress (Figure 30 and Figure 31).

Figure 30: Rychlik, cover of "Reverie" (Library of Congress)

Figure 31: Rychlik, "Reverie," opening (Library of Congress)

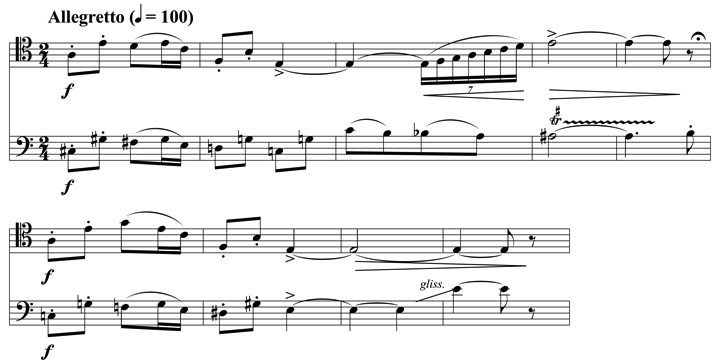

• Randall Thompson, Trio for Three String Basses. Thompson's most famous composition, the "Alleluia" (1940), was commissioned by Koussevitzky for Tanglewood. Thompson was tapped again for the Trio, composed in honor of Koussevitzky and premiered at the Harvard Club (of which Koussevitzky was a member) in 1949.81 The humor of this neo-Rococo work in four movements can only be fully appreciated in light of Thompson's description of the premiere: "It was solemnly programmed as 'Divertimento for Strings', to be performed by 'Members of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, Malcolm H. Holmes, '28, Guest Conductor'."82 The distinguished audience must have been quite surprised to see Holmes confronting three bassists. The work is in the general style of a classical period divertimento in four movements.

2. Koussevitzky composed some of his own performance repertoire.

4. Koussevitzky performed extant solo bass music, including concerti.

5. He also performed extant chamber music.

7. Other Transcriptions Associated With Koussevitzky, But Probably Not Performed

8. Repertoire Arranged Chronologically By Performance

9. Works Composed For Koussevitzky That He Never Performed

Sarah Lahasky, Editor

Editorial Board

Kathleen Horvath

Andrew Kohn

Shanti Nachtergaele

Fiona M. Palmer

Tae Hong Park

Sonia Ray

Phillip Serna

Usage Guidelines