Abstract: In the first decade of the 19th century, Giambattista Cimador arranged and published six chamber music reductions of symphonies by Mozart. The fourth arrangement in this set (entitled "Symphony IV") includes two movements from Mozart's Haffner Symphony (K. 385) and two movements from Mozart's Paris Symphony (K. 297/300a). This article explores the background and circumstances of Symphony IV's creation as well as Cimador's arranging techniques. Of particular interest are alterations Cimador made to articulation, slurring, and dynamics, as well as the use of polyphonic string writing relative to the source material. These alterations exemplify emerging approaches to string-playing and anticipate some important characteristics of 19th-century European music. A critical edition (including a score and parts) is included.

Double bassists frequently lament the relative paucity of quality chamber music when compared to the repertoire available to other string players. Raschen (2009) notes, "as chamber music developed into a dominant art form in the 19th century, the double bass retreated from a virtuoso role - playing concertos, chamber music and orchestral music - to a more supportive function that was delegated predominantly to the orchestra" (p. 3).

Certainly, some 19th century works such as Schubert's "Trout" Quintet Opus 114 and Dvorak's String Quintet Opus 77 are frequently programmed. Still, these rare gems do not come close to equaling the impressive breadth and depth of the string quartet repertoire. Within this context, it is surprising that Giambattista Cimador's (née Cimadoro) early 19th-century sextet reductions of Mozart's symphonies (with an optional seventh part for flute) have fallen out of favor (and out of print). They are rarely (if ever) performed or championed by contemporary double bassists. This was not always the case. Lister (2016) presents strong evidence Cimador's fellow Venetian Domenico Dragonetti performed these arrangements in London, where they were very well received. Italian violin virtuoso Giovanni Batista Viotti praised the arrangements with superlatives like "superb" and having "enchanted and astonished everybody" (p.3). "We can be reasonably sure," Lister adds, that he (Dragonetti), and Viotti, and four others played several, perhaps all six, of these works in at least two afternoon sessions" (p. 4).

Cimador's technical approach to the arrangements exaggerates some of the dramatic elements in the source material. His editorial choices reveal a preference for shorter musical phrases, more extreme dynamics, and a virtuosic approach to string playing employing double, triple, and quadruple stops to create a robust, orchestral sound from the small forces employed.

Cimador's six arrangements of Mozart's symphonies include some of the latter's most recognizable and enduring compositions such as K. 297/300a (no. 31 "Paris"), K.385 (no. 35, "Haffner"), K. 425 (no. 36 "Linz"), K. 504 (no. 38, "Prague"), and K. 550 (no. 40, "Great G minor symphony"). The British publisher Monzani (originally in collaboration with Cimador) published the performance parts between 1800 and 1827 without a score. The oldest parts in the British Library's collection are dated "1805" with a question mark attached to the date. Lister (2016) suggests a slightly earlier date for the publication, noting "Mozani and Cimador's edition…first appeared as early as 1800, when their partnership first began" (p.4). In any case, these works emerged at the dawn of the 19th century. The inspiration for this project, Lister implies, was likely the success of J. Salomon's 1798 quintet arrangements of Haydn's symphonies.

The fourth symphony in Cimador's set (entitled "Symphony IV") is both curious and captivating. Here, he combines four movements from two different Mozart symphonies, both in the key of D major. The odd-numbered movements are derived from K.385 (no. 35, "Haffner"), and the even numbered-movements are derived from K. 297/300a (no. 31 "Paris"). One can only speculate about Cimador's motivation for melding the two compositions. Certainly, they are stylistically similar and written just four years apart (1782 and 1778, respectively). Cimador may have been as captivated by the Paris symphony as Parisian audiences. In particular, the surprisingly sparse piano opening of the finale was of keen interest at the premiere. In Mozart's words,

Parisian audiences liked the Andante, too, but most of all the final Allegro because, having observed that here (in Paris) all final as well as first allegros begin with all the instruments playing together and generally unisono, I begin mine with the two violins only, piano for the first eight bars – followed instantly by a forte; the audience, as I expected, said "Shh!" at the soft beginning, and then, as soon as they heard the forte that followed, immediately began to clap their hands (Zaslaw, 1989, p.310).

Service (2014) adds further praise for the Paris Symphony's finale in describing it as "a miniature masterpiece because of how it layers some brilliantly worked counterpoint underneath the surface of its public spectacle" (para. 9). The Paris symphony, however, contains just three movements, while Cimador's other symphonic arrangements include four movements. By the 19th century, when Cimador published this set, the four-movement symphony was de rigueur. Burkholder, Grout, and Palisca (2020) note "Haydn's consistent use of this format (the four-movement symphony) helped to make it the standard for later composers" (p. 523). Both the Haffner and Paris symphonies are in the key of D major. Combining the second and third movements of the Paris Symphony with two movements of the Haffner Symphony allowed Cimador to present the Paris Symphony finale as part of a four-movement work in the same key.

In his edition, one minor change Cimador makes exaggerates the drama upon which Mozart commented in the Paris Symphony's finale. In the Neue Mozart-Ausgabe critical edition, the second violin part stays forte until the third beat of the bar. However, in Cimador's edition, the second violin part immediately drops to piano at the beginning of the bar, setting up a more dramatic contrast. Cimador may have been enamored by the "Shh!" effect the piano passage had on audiences (as described by Mozart). If he wanted to present the Paris Symphony finale in a four-movement context, the melding of the Haffner Symphony and Paris Symphony (both in D major) makes sense.

Cimador's arrangement includes a slow movement from Mozart's Paris Symphony. However, Mozart composed multiple versions of the slow movement for this work. The version from the first edition is 58 bars long and in 3/4 time (Tyson, 1981). The more frequently performed slow movement is in 6/8 time and "is today in the Musikabteilung of the Staatsbibliothek Preussischer Kulturbesitz in Berlin" and "often referred to as 'the autograph'" (Tyson, 1981, p.18). Two versions of the 6/8 slow movement exist as part of "the autograph" with minor discrepancies. The first 6/8 version is marked Andantino and contains several corrections and crossed-out bars. This is the version used for the 1880 edition published by Breitkopf and Härtel and has become more popular of late due to its availability as a free digital download on IMSLP (the International Music Score Library Project, also known as the Petrucci Music Library, accessible at www.imslp.org). The second 6/8 version is marked Andante and is nearly identical. This version was revised sometime after the second performance on August 15, 1778 (Tyson, 1981). The most noticeable difference between the Andantino movement and the Andante movement is the harmony in bars 73 – 76. In the Andantino version, the harmony is first in major and then in minor. The Andante version reverses this. Cimador's arrangement follows the 6/8 Andante version of the slow movement, with the aforementioned passage first in minor and then in major.

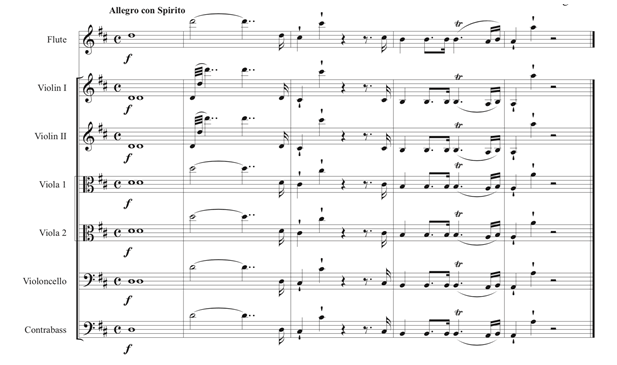

The original publication indicates some flexibility in the instrumentation. The title page bears the following inscription:

The bottom two parts are written in bass clef and clearly labeled "VIOLINCELLO" and "CONTRA BASS." However, the title page suggests some flexibility in Cimador's conception of the work. It seems likely that using a double bass on the lowest part is preferable, but the use of two celli is perfectly acceptable. The words "A German Flute" are presented in very large font and referenced near the bottom of the page with a curious inscription "NB: The Flute part being very beautiful and yet not absolutely necessary accounts for the APPARENT Contradiction in the terms OBLIGATO or AD LIBITUM" (Mozart, 1805). The description is apt. The flute part is not absolutely necessary but is used to add color and beautify the string writing. The flute part occasionally parallels the flute part in the original symphony and often embellishes the music Mozart originally assigned to the wind instruments. For example, in bars 59 – 66 of the first movement, Cimador begins by copying the original flute line and then switches to an embellishment of the Oboe I part:

Figure 1: Cimador edition flute part and Mozart wind parts from Movement 1, m. 59 – 66. Note how the Cimador flute part borrows from both the Mozart flute part and the Mozart oboe part.

Preparing a modern performance edition and score of the Mozart/Cimador Symphony IV presents challenges, many of which relate to articulation. Cimador's parts are inconsistent in their application of dots and strokes as articulation markings. In many ways, this makes sense, given the nature of the source material. Much ink has been spilt over the correct interpretation of dots and strokes in Mozart's music. As Riggs (1997) notes, "when examining the staccato notation in a Mozart autograph, two adjectives immediately come to mind: ambiguous and inconsistent" (p.239). Brown (1993) expresses a similar sentiment in stating "given the pervasive inconsistency of the articulation marks in Mozart's autographs, those of his contemporaries would certainly have been obliged to rely as much on musical intelligence as upon the apparent forms of the marks" (p. 594). Two schools of thought have emerged regarding dots and strokes in Mozart's music. The so-called "dualists" argue Mozart intended two distinct articulations. The Gesellschraft für Musikforschung adopted this position and "the consequences can be seen on nearly every page of the Neue Mozart-Ausgabe" (Riggs, 1997, p.232). Others advocate for a single staccato marking, noting, "Mozart could hardly have set great store by the graphic distinction" (Brown, 1993, p.594).

Like the source material, Cimador's Symphony IV is inconsistent in its application of articulation markings. The first inconsistent markings occur in bars three and five of the first movement. In the flute, violins, and viola prima part, Cimador employs a stroke as an articulation marking. In the viola seconda, cello, and bass part a dot is indicated. Did Cimador intend different articulations? It seems unlikely on musical grounds alone. Given the clear distinction in the parts between the dots and strokes, this edition preserves the character of Cimador's musical intention by incorporating the articulation employed in a majority of the parts and applying articulation consistently in all the parts. This solution should satisfy both those inclined to interpret the dots and strokes in the same manner and dualists preferring to distinguish between the two. It is worth noting that, in this passage, Cimador's edition eschews a stroke articulation on the 16th note pick-up to bar three in all parts. This approach differs from the Neue Mozart-Ausgabe, where a stroke articulation appears in all parts (see Figure 1).

Relative to the critical Neue Mozart-Ausgabe edition, Cimador's arrangement of Mozart's work in Symphony IV employs shorter slurred passages. Cimador, a string player himself, was often called upon to play violin or viola in the 1790s at social gatherings, and may have performed these arrangements himself (Lister, 2016, p.4). Given the depth of his understanding of string technique, the bowing choices Cimador made are surely intentional and reflect his approach to phrasing.

Cimador's alterations suggest changes in string performance technique and musical aesthetic preference between the late 1770s and early 1780s when the source material was composed and the early 19th century when the arrangements were published. Brown (1988) observed "during the first decade of the nineteenth century an aesthetic of string sound which stressed a singing style, expressive delivery, strong tone, forceful accents, and broad martelé bowstrokes in passagework seems to have been gaining ascendancy" (p. 101). Brown (1988) credits Giovanni Battista Viotti with spearheading this change and describes him as the "the greatest violinist of his day and the founder of a new style" of string playing at the turn of the 19th century (p. 102). Viotti's aforementioned praise for Cimador's arrangements are probably due (at least in part) to the latter's success in notating technical aspects of the string-playing aesthetics in vogue at the time and favored by Viotti.

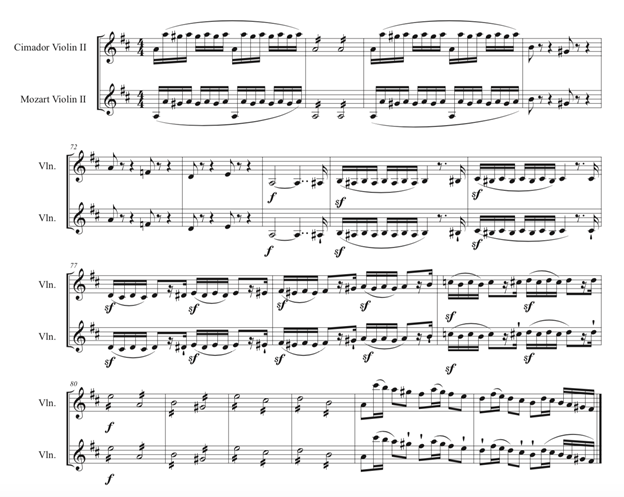

In general, Mozart's source material has longer slurs. Mozart also slurs fast passages into the following strong beat. Cimador, by contrast, prefers shorter slurs and changing the bow direction on a strong beat following a fast passage. These alterations likely helped contemporary string players express the new strong and forceful playing style described by Brown (1988). An example of the alterations is clear in the Violin II part between bars 68 and 85 in the first movement.

Figure 2: Violin II parts; movement 1, m 68-85. Note how the Cimador edition breaks the slur in all the 16th note passages.

Cimador employs a similar approach to the cadential material at the end of the first movement's exposition. The critical Neue Mozart-Ausgabe includes slurs into the downbeat while the Cimador edition breaks the slur after the 16th-note triplets at the bar line.

Figure 3: First Movement of the Haffner Symphony, Cimador Edition (m. 92 – 95). Note that the slurs in the 32nd notes and 16th note triplets do not extend to the next note.

Figure 4: String Parts from the First Movement of Mozart's Haffner Symphony (m. 92 – 95). Note that the slurs in the 32nd notes and 16th note triplets extend to the next note.

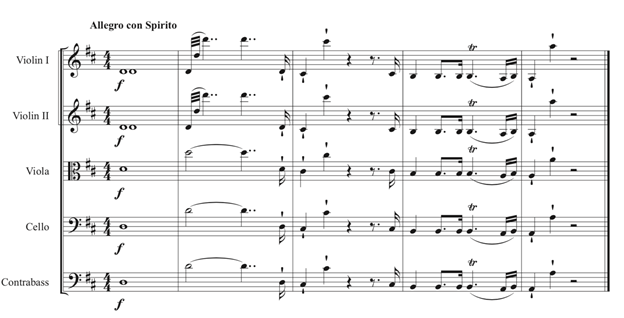

Cimador's expertise as a string player informs other aspects of his approach. He frequently employs the use of octave and unison doubling to thicken the timbre of the ensemble. Mozart uses this technique more sparingly, such as in the opening of the Haffner Symphony. Here, the violins play two pitches, one with the open string and one fingered note on the lower string in unison with the open string. By contrast, Cimador extends this approach to the violas and cello part, using the open D string to articulate unison double stops.

Figure 5: String Parts for the opening of Mozart's Haffner Symphony. Note that the unison double stops are restricted to the violin parts.

Figure 6: Opening of Cimador's arrangement of the Haffner Symphony. Note the use of double stop octaves in the viola parts and the cello part.

Cimador finds many additional opportunities to employ this approach throughout the arrangement. Mozart uses unison and octave double stops only in the violin parts while Cimador extends this approach to the viola and cello part.

Figure 7: Cimador Edition, Movement 1, m. 59 – 66. Note the unison double stops on D and A.

Neither composer employs unison or octave doubling in the double bass part, although we know Cimador was familiar with octave doublings for this instrument since he previously used them in the solo part of the double bass concerto he composed (Heyes, 2015; Slatford & McClymonds, 2001).

Cimador's use of fuller chords in the string writing extends to the use of quadruple stops. Quadruple stops are not used in the source material at all.

Figure 8: Cimador edition, viola I part, Movement 1, m. 201 – 204. Note the use of quadruple stops.

Unlike the source material, Cimador makes use of pp and ff dynamics for contrast. The exaggerated dynamics are most noticeable in the flute part, which uses four ff dynamic markings in the first movement. Perhaps Cimador was concerned about the flute's ability to project. Also, in the first movement, Cimador notates pp in m.67 and ff in m.105 where the source material indicates a more restrained p and f, respectively.

Cimador's work can hardly be described as "Romantic," but it is worth pointing out that his edition was released around the same time Beethoven composed the Eroica symphony (1802 – 1804) and remained in print until the year of Beethoven's death (1827). In this context, one can understand Cimador's use of expanded dynamics, fuller string textures, and more strongly articulated gestures relative to the source material as part of the cultural and aesthetic zeitgeist that would come to define European concert music of the 19th century.

Future research related to Symphony IV might begin with the other five arrangements in this set. What changes does Cimador make to the source material? Is his approach in the other reductions similar or different to this one? What do his choices reveal about changing musical tastes and techniques at the beginning of the 19th century?

We have good reasons to believe that the double bass virtuoso and composer Dragonetti performed these arrangements and that Cimador composed his one double bass concerto for Dragonetti. How did these two Italians who spent much of their life in England influence one another? In what ways are Cimador's symphonic reductions similar or different to Dragonetti's string quintets?

Symphonic double bass parts in Mozart's time usually doubled the cello part. By the end of the 19th century, symphonic double bass parts were usually independent. What role (if any) did early 19th-century symphonic reductions with independent double bass parts (like the ones created by Cimador) play in the development of independent double bass parts in later 19th-century symphonic music?

Biba, O., Jones, D. W., & Landon, H. C. R. (Eds.) (1996). Studies in Music History: Presented to H.C. Robbins Landon on His Seventieth Birthday (First edition.). Thames & Hudson.

Brown, C. (1988). Bowing Styles, Vibrato and Portamento in Nineteenth-Century Violin Playing. Journal of the Royal Musical Association, 113(1), 97–128.

Brown, C. (1993). Dots and strokes in late 18th- and 19th-century music. Early Music, 21(4), 593–610.

Burkholder, J. P., Grout, D. J., & Palisca, C. V. (2019). A History of Western Music (Tenth edition). W. W. Norton & Company.

Busse, T. (2012). New Esterházy Quartet Bridges "Pop" and Highbrow Haydn. View Website

Detmer, R. (n.d.). Serenade No. 7 for orchestra in D… | Details. AllMusic. Retrieved June 3, 2021, from View Website

Developers, S. B. B. (1788). Sinfonien; orch; D-Dur; KV 297; KV 300a. Retrieved June 22, 2021, from View Website

Everist, M. (2013). Mozart's Ghosts: Haunting the Halls of Musical Culture. Oxford University Press.

Harnoncourt, N. (2009). Musik als Klangrede. Residenz Verlag.

Heyes, D. (2015). A History of the Double Bass in 100 Pieces—Posts | Facebook. View Website

Judd, T. (2016). Mozart's "Haffner" Symphony: Music of Celebration. The Listeners' Club. View Website

Lister, W. (2016, Winter). Dragonetti, Viotti and those superb sextets of Mozart. Musical Times, 157(1937), 3-5,2.

Luoma, R. G. (1976). The Function of Dynamics in the Music of Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven: Some Implications for the Performer. College Music Symposium, 16, 32–41.

Mozart, W. A. (2006). Neue Mozart-Ausgabe: Digital Mozart Edition [[Electronic resource] =]. Internationale Stiftung Mozarteum.

Neumann, F. (1993). Dots and Strokes in Mozart. Early Music, 21(3), 429–435.

Range, M. (2012). The "Effective Passage" in Mozart's "Paris" Symphony. Eighteenth-Century Music, 9(1), 109–119. View Website

Raschen, G. (2009). Chamber Music with Double Bass: A New Approach to Function and Pedagogy. 36.

Riggs, R. (1997). Mozart's Notation of Staccato Articulation: A New Appraisal. The Journal of Musicology, 15(2), 230–277. View Website

Service, T. (2014). Symphony guide: Mozart's 31st ('Paris') | Classical music | The Guardian. View Website

Slatford, R. (1970). Domenico Dragonetti. Proceedings of the Royal Musical Association, 97, 21–28.

Symphonies: No. 31 in D/No. 33 in B♭/No. 34 in C: EBSCOhost. (n.d.). Retrieved June 21, 2021, from View Website

Slatford, R., & McClymonds, M. P. (2001). Cimador [Cimadoro], Giambattista. Grove Music Online. View Website

Tyson, A. (1981). The Two Slow Movements of Mozart's Paris Symphony k297. The Musical Times, 122(1655), 17–21. View Website

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. (1805). No. 1 of Mozart's Grand Symphonies arranged as Sestettos, with additional Wind Instruments ad libitum for a Full Band by I. B. Cimador. [Parts.]. Printed for Theobald Monzani, 1805?

Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart. (1806). No. 1 of Mozart's grand symphonies / Arranged as sestettos, with additional wind instruments ad libitum for a full band by I.B. Cimador. printed for Theobald Monzani, 1806?

Zaslaw, N. (1978). Mozart's Paris Symphonies. The Musical Times, 119(1627), 753–757. View Website

Zaslaw, N. (1991). Mozart's Symphonies: Context, Performance Practice, Reception (n edition). Clarendon Press.

Dr. Mark Elliot Bergman is the Director of Strings and Orchestral Studies at Sheridan College. He directs the Sheridan College Symphony Orchestra and the Sheridan College Viol Consort. Additionally, he teaches bass, cello, viola da gamba, electric bass, and composition lessons. In 2018, Mark received the Wyoming Performing Arts Fellowship, recognizing his state-wide contributions as a composer and performer.

Mark is the Assistant Principal Bassist of the Billings Symphony Orchestra, a section bassist with the Britt Festival Orchestra (Oregon), and a chamber musician with Assisi Performing Arts (Italy). He formerly served as the Principal Double Bassist of the New Haven Symphony Orchestra, Mato Grosso State Orchestra in Cuiabá, Brazil, and the Alexandria Symphony Orchestra. In 2011, the Arts Council of Fairfax County (Virginia) awarded him the Strauss Fellowship for his work as a composer. Cognella Academic Press published his first book, In The Groove: Form and Function in Popular Music, in 2012. His second book, Get Up, Stand Up! Higher Order Thinking in Popular Music Studies was published by Scholars Press (2016). Mark earned his doctorate from George Mason University in 2015. He also holds degrees from Yale University, the Eastman School of Music, and the Manhattan School of Music, where he studied with Orin O'Brien.

© 2003 - 2026 International Society of Bassists. All rights reserved.

Items appearing in the OJBR may be saved and stored in electronic or paper form, and may be shared among individuals for purposes of scholarly research or discussion, but may not be republished in any form, electronic or print, without prior, written permission from the International Society of Bassists, and advance notification of the editors of the OJBR.

Any redistributed form of items published in the OJBR must include the following information in a form appropriate to the medium in which the items are to appear:

This item appeared in The Online Journal of Bass Research in [VOLUME #, ISSUE #] in [MONTH/YEAR], and it is republished here with the written permission of the International Society of Bassists.

Libraries may archive issues of OJBR in electronic or paper form for public access so long as each issue is stored in its entirety, and no access fee is charged. Exceptions to these requirements must be approved in writing by the editors of the OJBR and the International Society of Bassists.

Citations to articles from OJBR should include the URL as found at the beginning of the article and the paragraph number; for example:

Volume 3

Alexandre Ritter, "Franco Petracchi and the Divertimento Concertante Per Contrabbasso E Orchestra by Nino Rota: A Successful Collaboration Between Composer And Performer" Online Journal of Bass Research 3 (2012), <http://www.ojbr.com/volume-3-number-1.asp>, par. 1.2.Volume 2

Shanon P. Zusman, "A Critical Review of Studies in Italian Sacred and Instrumental Music in the 17th Century by Stephen Bonta, Burlington, VT: Ashgate Publishing Co., 2003." Online Journal of Bass Research 2 (2004), <http://www.ojbr.com/volume-2-number-1.asp>, par. 1.2.Volume 1

Michael D. Greenberg, "Perfecting the Storm: The Rise of the Double Bass in France, 1701-1815," Online Journal of Bass Research 1 (2003) <http://www.ojbr.com/volume-1-complete.asp>, par. 1.2.

This document and all portions thereof are protected by U.S. and international copyright laws. Material contained herein may be copied and/or distributed for research purposes only.