Volume 6, August 2015

|

| Beethoven's version: | Müller's modification: |

|

|

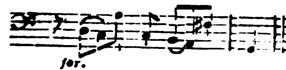

Müller claims that the passage occurring in mm. 80 - 90 of the same movement should be reduced in order to conserve energy (see figure 4), but Franke opposes the simplification and states that the several indiscriminate changes that Müller suggests cannot be allowed.lxxi This disagreement again demonstrates the difference between the two players' concepts of double bass playing: Müller is concerned with stamina and having enough strength for a solid performance, and will cut out notes to achieve this end; while Franke adheres more closely to the prescribed notes, and is more optimistic about double bassists' stamina and technical abilities. Unfortunately, one can only speculate about whether Franke and others who followed his line of thought were successful in faithfully performing the written parts as powerfully as Müller and his fellow simplifiers.

Figure 4. Müller's reduction of Beethoven, Symphony no. 5, movt. 4, mm. 80 - 90.lxxii

Beethoven's version (mm. 80 - 85):

Müller's reduction (mm. 80 - 90):

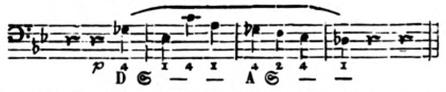

Some of Franke's objections stem from the two bassists' contradicting ideas about fingering. In general, Müller's fingerings require more shifting and avoid open strings whenever possible, while Franke's fingerings utilize open strings in order to avoid shifting. An example of their differing preferences can be seen in mm. 16 - 17 of the first movement of the Second Symphony (see figure 5). Müller permits the open D in order to facilitate the required crescendo, but then continues up the D string with a closed G.lxxiii Franke however suggests playing the entire passage in one position with the G and A-flat on the G string, though he also instructs that the open strings be played with the proper tone color.lxxiv

Figure 5. Fingerings for Beethoven, Symphony no. 3, movt. 1, mm. 16 - 17.lxxv

Franke seems to misinterpret some of Müller's fingering suggestions, for he claims that Müller at times indicates reaching a minor third in one position: a span that is possible using Franke's system, but not Müller's. In each case however, the fingerings that Müller writes can in fact be executed using his own 3-finger system. The three examples that Franke sets forth are from the first movement of the Third Symphony, the third movement of the Fourth Symphony, and the fourth movement of the Sixth Symphony.

Franke apparently assumes that the minor thirds in these examples are intended to be executed without shifting, which he supports by quoting Müller's statement, "This shift, because it generates clumsy playing, is always reprehensible!"lxxvi However, referring to the quote in its original context in Müller's article reveals that Franke has misinterpreted Müller's words. Müller is not referring to shifting in general here, but rather specifically to shifting from one note to another with the fourth finger. That being the case, shifting from first finger on E-flat to fourth finger on G-flat, as Müller indicates for mm. 346 - 347 of the first movement of the Third Symphony, would be perfectly acceptable (see figure 6).

Figure 6. Müller's fingering for Beethoven, Symphony no. 3, movt. 1, mm. 346 - 347.lxxvii

Franke's next example, mm. 6 - 9 of the third movement of the Fourth Symphony, also suffers from missing information. The example shown comes from Müller's article (see figure 7), while Franke's version does not contain Müller's fingerings or string indications, and is truncated to the first beat of m. 8. Franke therefore only shows the descending minor thirds of G-flat to E-flat and C to A, which he hopes to convince readers should be played in a single 4-finger position, while in fact Müller clearly indicates that a great deal of shifting is necessary. According to Müller, the first four notes spanning a major sixth are all to be played on the D string, which requires shifting between each note; and the last four notes are to be executed in two positions on the A string. As Müller explains, one would have to shift numerous times anyway, and this rather unorthodox fingering at least helps one to achieve an even tone and calm bow because it avoids too many string crossings.lxxviii

Figure 7. Müller's fingering for Beethoven, Symphony no. 4, movt. 3, mm. 6 - 9.lxxix

In reference to the excerpt that begins in m. 64 of the fourth movement of the Sixth Symphony, Franke adds that he does not know of a rule that allows for the second finger to play the C-sharp, and that the third finger should be used instead (see figure 8).lxxx While the third finger would be logical for someone using all four fingers, in the 3-finger system one would most likely shift from first finger B to second finger C-sharp so that the D could then be played with the fourth finger, thereby avoiding the 'reprehensible' fourth-to-fourth finger shift from C-sharp to D.

Figure 8. Müller's fingering for Beethoven, Symphony no. 6, movt. 4, m. 64.lxxxi

While Franke does not comment on Müller's other suggested simplifications, two excerpts from the Sixth Symphony do prompt additional consideration. First, in the fourth movement Müller reduces the recurring figure that first appears in mm. 21 from sixteenth notes to eighth notes (see figure 9). He suggests that the double basses only play the notes that outline the harmony — while the cellos play the full motive — because continuously playing such loud and fast notes would result in a mess.lxxxii A common opinion among modern bassists, however, is that this particular passage is actually allowed, or even intended, to be somewhat 'messy' to create an effect. This movement of the symphony is titled "thunderstorm," and the fast, loud, low, and slurred notes played by the cellos and basses in this passage are thought to depict thunder. Müller's reduction makes the figure easier to perform, but it may also reduce the passage's resemblance to rumbling thunder. Nevertheless, a programmatic work can suggest an idea without exactly imitating its sound; Beethoven himself described his symphony as "more sentiment than tone painting," perhaps indicating that performers should aim to evoke the emotions associated with experiencing a thunderstorm rather than attempt to imitate its sound.lxxxiii

Figure 9. Müller's reduction of Beethoven, Symphony no. 6, movt. 4, mm. 21 - 22. Müller notates Beethoven's version with stems pointing up, and his own suggested modification with stems pointing down.lxxxiv

Müller's suggested modification of mm. 43 - 50 of theSixth Symphony is unique in that he suggests changes to a section in which Beethoven has already given the cellos and double basses independent parts (see figure 10). Müller reasons that transposing the lower notes up an octave improves clarity in the passage, and he confidently proclaims that Beethoven himself would approve of this change.lxxxv However, there are some indications that Beethoven had a very specific double bass part in mind in this section, and that the composer was perhaps even trying to avoid the modifications that Müller suggests.lxxxvi It was common practice in Beethoven's time — when a single part was usually written for the cellos and double basses — for double bassists to transpose any notes that fell below the range of their instrument (in Müller's case, a notated E). The transposition was generally applied to a whole passage in order to preserve its contour: in other words, to avoid breaking up the musical line.lxxxvii According to this rule, it would be logical to transpose the entire motive in question as Müller does, in order to maintain the same contour in both the double bass and cello parts. In this case however, Beethoven writes the passage so that the double basses enter an octave below the cellos, and then he breaks the double bass line so that only the last two sixteenth notes of the motive are played in unison with the cellos. If Beethoven expected double bassists to be inclined to transpose the motive from the beginning, he may have created a separate double bass part to indicate that the double basses should not follow common performance practices in this instance.

Figure 10. Müller's modification of Beethoven, Symphony no. 6, movt. 5, mm. 43 - 48.lxxxviii

Original:

Müller's suggestion:

As highlighted by the example above, the matter of when and how to modify double bass parts in nineteenth-century orchestral works is complex. Beethoven's symphonies are among the earliest orchestral works to include sections with independent double bass parts, and early-nineteenth century double bassists would have seen these parts as unique. Criticisms of 'simplifiers' suggest that nineteenth-century composers may have started writing separate double bass parts as an attempt to discourage undesirable modifications.lxxxix Even with independent parts, some double bassists who were used to simplifying their parts would likely have continued the practice out of habit. It appears that Müller was one of those performers who adhered to the old tradition, while Franke was more inclined to follow the developing trends in compositional and performance practices.

1. Introduction: Franke and Müller's debate

2. The role of the double bass

3. The level of double bass playing

4. Construction and set-up of the instrument

8. Components of daily practice

9. Performing Beethoven's symphonies

Appendix — translations of cited foreign texts

For access to the full PDF document of this article, please go to http://www.researchcatalogue.net/view/103988/135390.

Sarah Lahasky, Editor

Editorial Board

Kathleen Horvath

Andrew Kohn

Shanti Nachtergaele

Fiona M. Palmer

Tae Hong Park

Sonia Ray

Phillip Serna

Usage Guidelines