| |

Volume 8, January 2017

Revolution in Action: A Motivic Analysis of "Ghosts: First Variation" As Performed by Gary Peacock

by Robert Sabin, Ph.D.

3. Ghosts: First Variation Overview

Ghosts captures Peacock's tone and unfettered free playing in one of the most influential of Ayler's compositions. Individual saxophone and bass improvisations follow Ayler's raucous, celebratory, diatonic, and in-time melody7(Figures 1-3). The folk-like character of the composed line contrasts starkly to the improvisations that will follow. Indeed Peacock's accompaniment underneath Ayler's solo improvisation is experienced as a concurrent extemporization of its own, with little recognizable connection to common practice accompaniment roles. The dynamic and rhythmically dense torrent of gestures in Peacock's playing can be characterized partially by the lack of predetermined rhythmic and melodic referents, extreme harmonic mobility, and oblique (if any) relationships to thematic or harmonic sequences contained in the head. Peacock's furiously active performance primarily takes the form of a kind of integrated rhythmic surge, responding to Ayler and Murray's playing with a myriad of fleeting melodies, tempos, timbres, and dynamic gestures that maintain complex motivic characteristics despite what has been dismissed as "satirical comedy"8 due to these potentially impenetrable layers of surface level complexity.

Figure 1. Measures 1-25

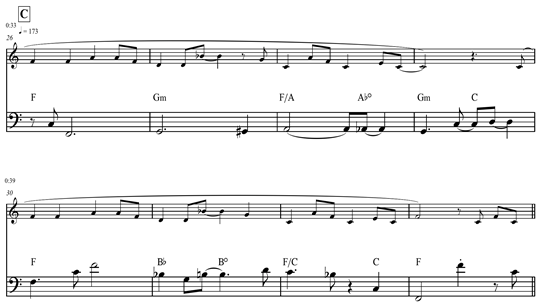

Figure 2. Measures 26-33

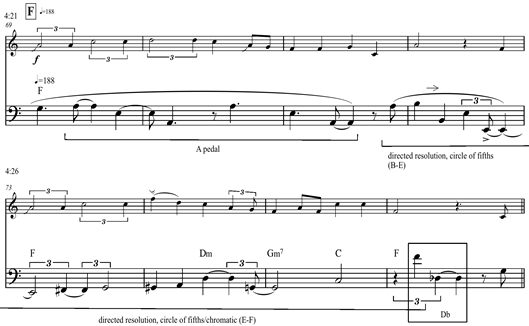

Figure 3. Measures 69-76, out head. Peacock prolongs his circle of fifths gesture in m. 72 by connecting E to A in a linear chromatic fashion before the deceptive resolution of the phrase to Db.

Peacock's playing displays several principle characteristics throughout the recording: 1) it can be broken down into a series of discreet yet overlapping phrases, with onset and offsets separated by rest or stark changes in register, dynamic, and/or tempo; 2) phrases contain discreet and observable contour, intervallic, rhythmic, pitch content, and expressive characteristics; 3) the flow of these phrases is rapid and intensely dense, offering an abundant production of diverse ideas with only rare instances of substantial pause; 4) phrases demonstrate extreme virtuosity and formidable technical demands inherent to their execution; 5) Peacock's playing is essentially responsive in nature, with the nature of these responses (to other musicians or to previous phrases played by the bassist himself) creating an ever increasing volume of moment to moment contrast; 6) the playing displays, according to Peacock9 a lack of self-consciousness that would impede the exceptional velocity and timing characteristics displayed throughout; 7) phrases contain a variety of discernable tempos, sometimes rapidly changing, yet measurable through measure and markings.

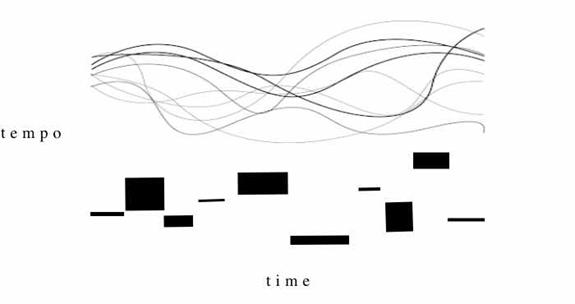

Pulse and tempo, as a defining characteristic of Peacock's improvisation, is maintained, albeit with rapid moment-to-moment changes and phrase-to-phrase developments. These tempos will be notated throughout using approximate (≈) tempo markings. These discernable tempos (and, more importantly, the shifts between them) combine with Ayler's expressive and unorthodox phrasing, creating a potential for increased perceptual dissonances (acknowledging that perceptual dissonance is relative and unprovable in some cases) via the creation of multiple and dissimilar juxtapositions of musical time, harmony, timbre, and densities. These unpredictable changes in tempo also serve as primary variations in perceived energy and motion, a unique contribution by Peacock to the ensemble that often contrasts the approaches heard from Ayler and Murray. Figure 4 demonstrates the nature of these contrasts via a two-dimensional modeling of Peacock's comparatively terraced approach to tempo, underneath the gradually shifting levels of density and velocity that make the specific notation of a regular pulse in the notation of the saxophone improvisation often illogical and/or impractical.

The juxtaposition of speeds and unpredictable compression and expansion of rhythm in each player's improvisation will now be characteristic for the remainder of the performance, creating a strong rhythmic polyphony that can obscure the perception of individual rhythms, as well as a perpetual motion from the ensemble as a whole that can potentially consume the details within the individual parts. The density of the rhythmic interplay often prevents the initial perception of these individual melodies due to substantial interference from other players' contributions. The constant interplay of these various speeds contributes to an ensemble texture that consumes any fleeting tempo information contained within individual phrases. This could initially suggest that Peacock is playing in a stream of consciousness manner, utilizing a kind of evolved rubato devoid of more detailed rhythmic components. However, these components do exist, and with a tremendous degree of observable detail.

Figure 4. A perceptual diagram of concurrent velocities; Ayler (top) and Peacock (bottom). While Peacock segments his accompaniment into short fragments with clear yet unpredictable tempo changes from one phrase to the next, Ayler's solo accelerates and/or slows within the characteristically long phrases themselves without a constant articulation of unwavering tempo.

|

|